Archives Experience Newsletter - May 17, 2022

A Window to War

In 1965, television brought images and scenes of war into American homes. In just a decade, the percentage of Americans with a TV skyrocketed from 9% to 93%. Since the Vietnam era, the American public’s view of armed conflict has become far more accessible. Cable news gave us 24/7 coverage of the wars in both Iraq and Afghanistan. Twitter gave the Arab Spring revolutions a platform; most recently, our youngest generation watched Russia’s invasion of Ukraine via TikTok.

If cable news and social media are the windows into war today, the nineteenth-century window was the photograph. Mathew Brady, born 200 years ago this year, captured more than 12,000 photos of the Civil War with his team. These weren’t painted battlefield landscapes or portraits of decorated war heroes; rather, they were up close and personal images: mangled bodies, prisoners of war, and destroyed cities. These images were printed in newspapers everywhere, and they served to shatter the public’s romanticized visions of war.

The National Archives is home to more than 6,000 of Brady’s photos. The Civil War killed more than one-third of our country’s men and nearly tore our nation apart. Brady’s images serve as a reminder of the cost of conflict, even now.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

P.S. Brady’s images are powerful, which also makes some of them hard to look at. Our first story contains graphic images.

Reality Hits

Before the advent of photography, depictions of war were largely written descriptions in newspapers and fiction and visual renditions in paintings and drawings, most of which tended to be rather romantic. “It is sweet and fitting to die for the homeland,” the Roman poet Horace insisted, and until people experienced the horrors of the battlefield themselves or heard the reports of people who had seen action, they may have agreed with that sentiment.

In the United States, the work of Civil War photographer Mathew Brady changed all that. Because the photographic equipment of the time was huge and cumbersome, Brady and his many assistants could not photograph a battle in progress, but their graphic images of the dead lying on the battlefields and being prepared for burial and of grim scenes such as amputations at hospital tents brought the realities of war home in graphic detail to those who had no idea of their true horrors. Mathew Brady is quite accurately considered the father of modern photojournalism.

Indeed, Brady’s substantial investment in the war as a subject that eventually contributed to his downfall as a businessman. During the war, he amassed a huge collection of Civil War scenes that he hoped the U.S. government would buy from him. But when the war ended, people were no longer interested in looking at his photographs—they were painful reminders of the catastrophic price the nation had paid for four long years—and demand for them plummeted. The government declined to buy Brady’s collection, and he was forced to sell his studio and declare bankruptcy. He died penniless in New York City in 1896.

Romanticized/sanitized perceptions of war

Realities of War portrayed by Brady…

Cartes de Visite

In the nineteenth century, when people called at a friend’s home and found the friend wasn’t there, they left a calling card, a small card about the size of a modern-day business card printed with their name and sometimes their address. The card let the occupant know that someone had called while they were away.

In 1854, the Parisian photographer André Adophe Eugène Disdéi patented the carte de visite, a thin photograph roughly 2 ¼ high by 3 ¾ inches long, about the size of a traditional calling card, that was mounted on heavier card stock. Cartes de visite became very popular very quickly. The trend spread from Europe to America as people passed them around to their friends.

By 1849, Mathew Brady had photography studios in both New York City and Washington, D.C., and much of his business was devoted to producing cartes de visite. To a large degree, he counted on life’s uncertainty to persuade his customers to preserve and share their images with their loved ones. In 1856, he ran an advertisement in The New York Daily Tribune that urged people to have cartes de visite made, cautioning them, “You cannot tell how soon it may be too late.”

But it was the Civil War that really brought a boom to Brady’s carte de visite business, bringing soldiers by the scores to his studios to have their portraits made before they left for the war. Mathew Brady soon became interested in photographing the war up close and personal, and he became famous for his portraits of presidents, generals, and the celebrities of his time, but the humble carte de visite still turns up among family heirlooms and in the holdings of museums and the National Archives.

Seeking Refuge

An Act Respecting Escapees from Justice and Persons Escaping from the Service of their Masters

National Archives Identifier: 44272943

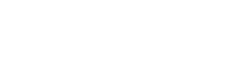

When Union troops began to cross into Confederate territory, enslaved Black people started to escape from their owners and run for the Union lines, seeking their freedom. Many brought their families and a few possessions on horseback or in wagons, but others left with only the clothes on their backs and what little they could carry.

The original Fugitive Slave Act was signed into law by George Washington in 1793. It allowed owners of slaves to reclaim them if they escaped, and made aiding an escaped slave a crime. The Act was strengthened in 1850 to allow slaves captured in the North to be returned to the South.

Read more about the Fugitive Slave Act here

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

Stereographs of the Civil War

National Archives Identifier: 44272943

At the beginning of the Civil War, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was still the law of the land, but once the war broke out, many Union army officers refused to enforce it and granted sanctuary to enslaved persons who reached their lines. On August 6, 1861, the federal government declared that the enslaved who escaped to the Union were “contraband of war” if their labor had aided the Confederacy, and as such, they were declared free.

This photograph from the Brady Archive shows a black family in a wagon crossing into the Union lines.

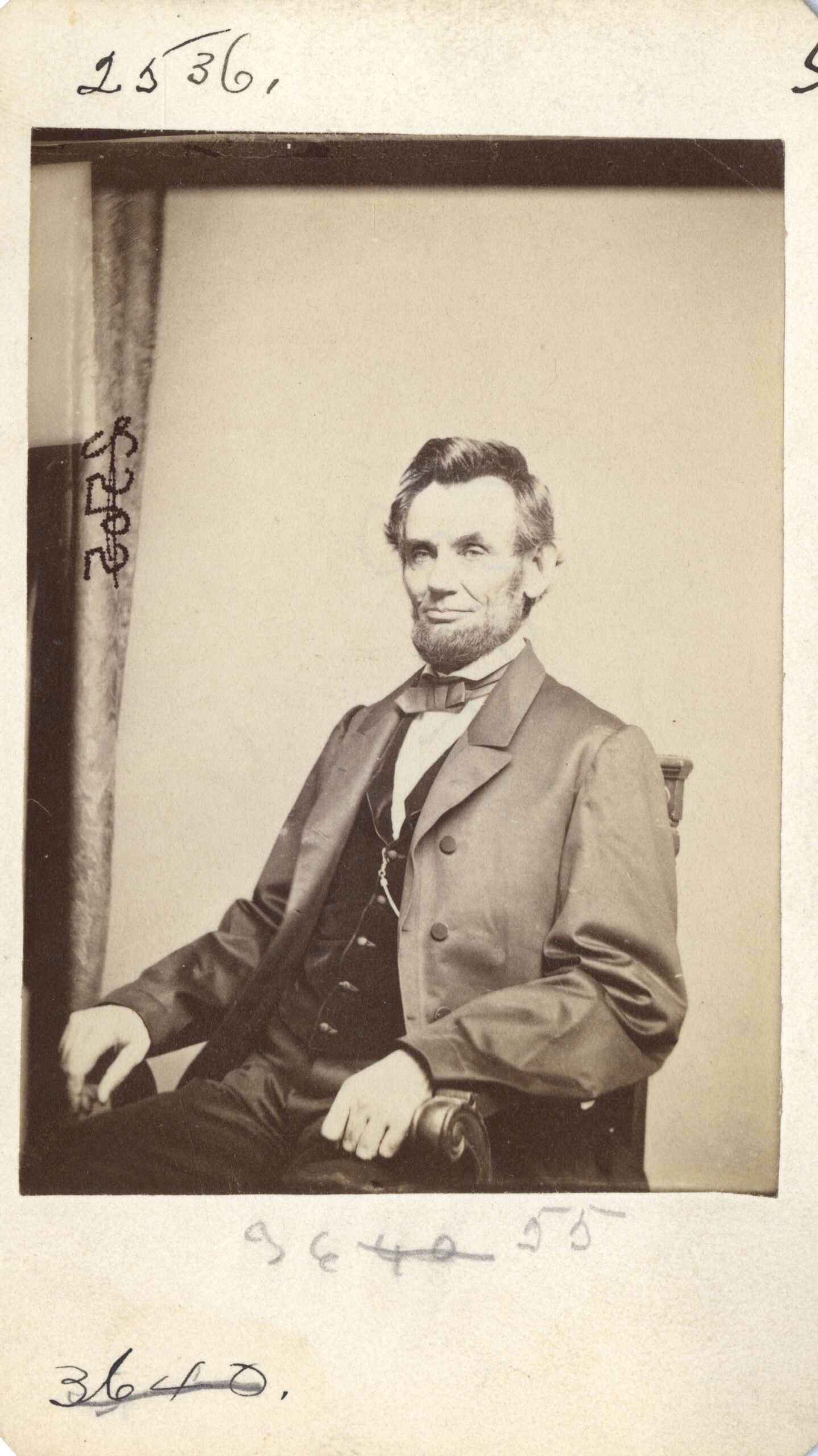

An Iconic Image

Abraham Lincoln, President, U.S.

National Archives Identifier: 167249680

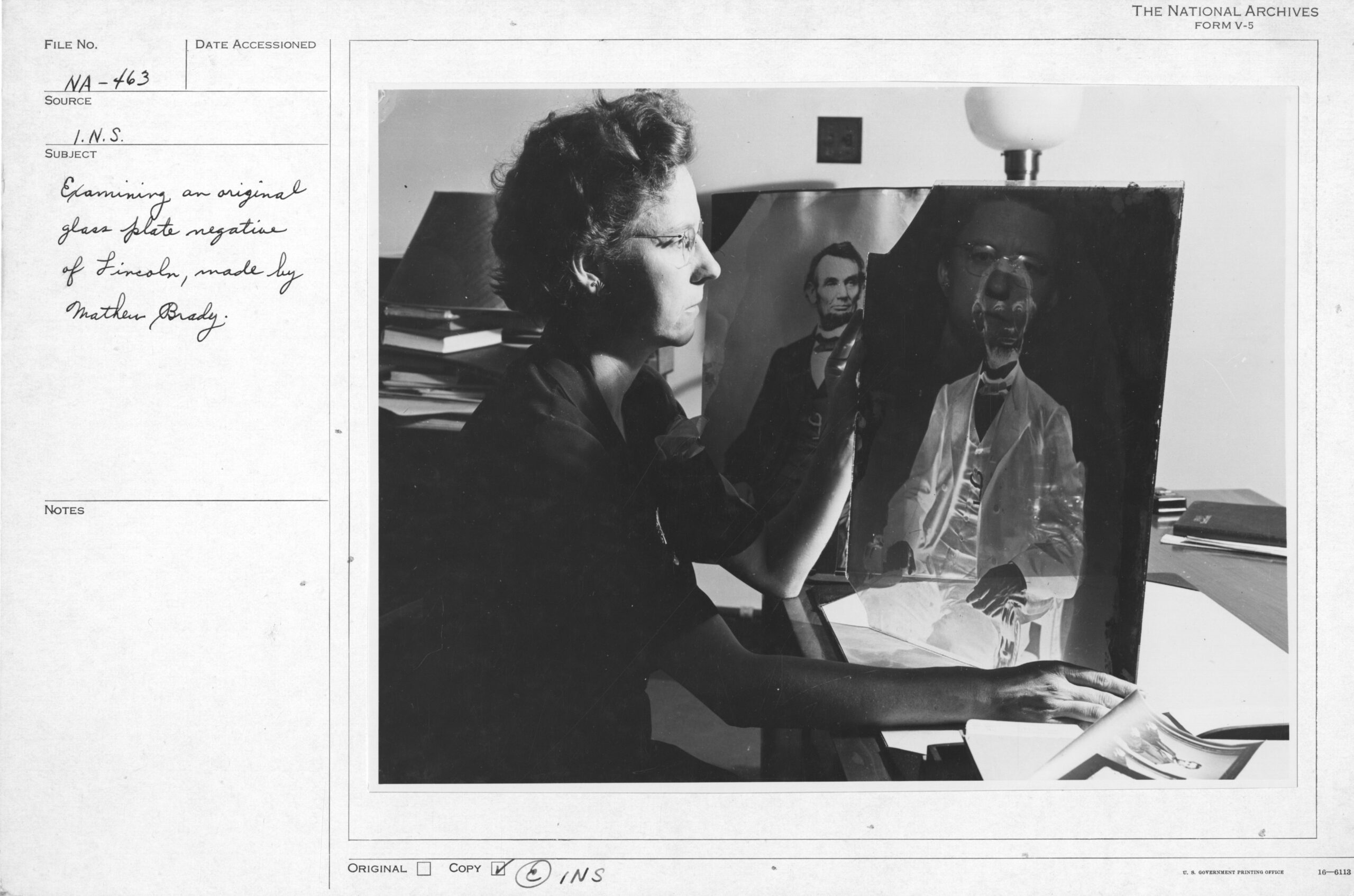

Josephine Cobb Examining Lincoln Negative by Mathew Brady

National Archives Identifier: 18519913

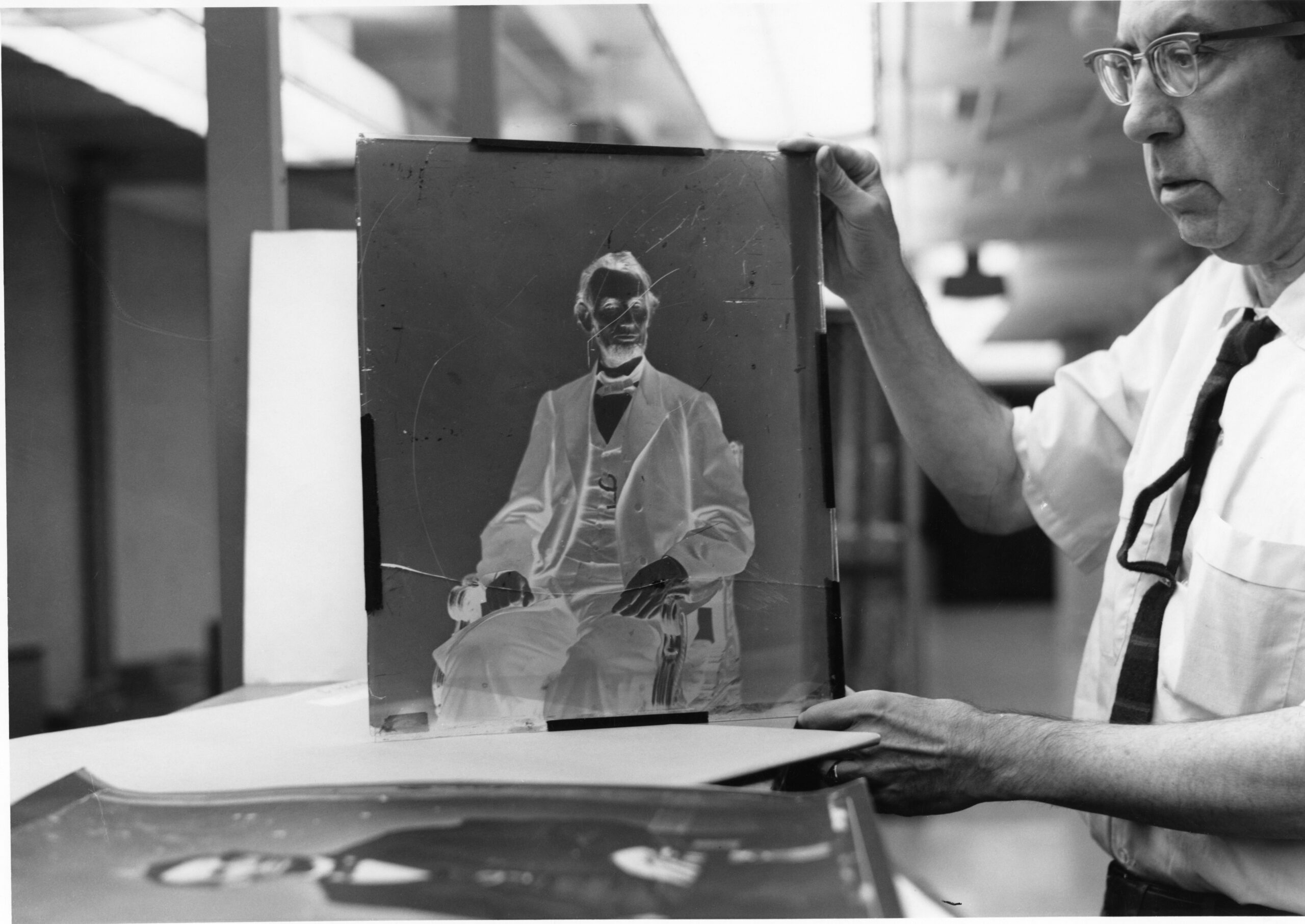

Archivist with Damaged Negative of Abraham Lincoln

National Archives Identifier: 102252890

The American Civil War ended more than 150 years ago, but the work of photographer Mathew Brady is still part of our everyday lives. This portrait of Abraham Lincoln, which Brady himself made on January 8, 1864, has become one of the most iconic images of the sixteenth President of the United States. The images of Lincoln on the five-dollar bill and the Lincoln penny are based on photographs produced by Brady Studios.

Today, this image lives at the Archives, where NARA archivists are still working to preserve the image. On the right, you can see them working with the negatives.

Civil War Scenes

Mathew Brady and his assistants covered a lot of ground during the Civil War, and they photographed not only many people, both well-known and obscure, but many important landmarks. Here are just a few, displayed in the carousel below:

- Fort Sumter – where the first shots of the Civil War were fired

- View of Gettysburg – the northernmost battle

- Harper’s Ferry – where John Brown staged his famous raid, and a strategic area of control for both the Union and Confederate armies

- Yorktown, VA – see the place of General Cornwallis’s surrender (Revolutionary War) during another conflict almost 100 years later

- Barricades in Alexandria, VA – known as the “crossroads of the Civil War” for being a “melting pot” of Union and Confederate wounded, civilian nurses, and enslaved “contraband”

- Battlefield of Antietam – site of a key Union victory

- Jefferson Davis House in Richmond – home of the Confederate President

- Robert E. Lee’s House with Union Soldiers – home of the leader of the Confederate Army, site of Arlington National Cemetery today

- Richmond after the evacuation – Capital of the Confederacy

- Appomattox Court House, VA – site where General Lee surrendered to General Grant