Who Will You Find?

Last Friday was a day 72 years in the making – the release of the 1950 Census! This Census release is particularly special, because it’s the first time many of us will see parents, grandparents, or other relatives counted, documented, and searchable in the Archives.

While most Americans’ interactions with the Census is filling out a quick form every 10 years, the combined document is so much more than that. There are the modern day implications of political representation and funding for communities, but the Census is also critical to providing links to our past and understanding our shared American story. A single name on a ledger line could be the long-lost grandparent someone’s been searching for, or an address listed could have been an old family home. In the first few days, I’ve found my grandparents, parents, aunts and uncles listed, but the Census isn’t just a list, it’s stories waiting to be uncovered.

Whether you’ve been doing family research for years or this 1950 Census release has piqued your interest, the Census edition of our newsletter has something for you! Read on for the “best of” the 1950 Census and advice from expert researchers at the Archives.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Standout Stories

It’s All Relative: Locating Family in Federal Records and Genealogy Research Strategies

in NARA’s Rediscovering Black History | Say It Loud blog

Information from the 1950 census is now available via the National Archives website, and genealogists everywhere are very excited to wade into it. Whether you’re experienced at tracking down genealogical information in census records or this is your first venture, the archivists at the National Archives have your back.

Check out Archivist Miranda Booker Perry’s blog post “It’s All Relative: Locating Family in Federal Records and Genealogy Research Strategies,” in which she describes in detail how she used the census to track down information about members of both sides of her family. One sweet fact she uncovered in census records is that her first-great-grandparents were neighbors before they became engaged.

Deputy Archivist Debra Wall has a standout census story of her own. Like so many of us, she began her genealogy research with a popular commercial DNA test. Her goal was to locate her father’s birth parents – her biological grandparents. When a close DNA match surfaced years later, census records at NARA helped fill in the gaps. Before long, she not only identified her father’s birth parents, but also his seven half-siblings and her newly discovered biological half-cousins. If you’re looking for ways to connect your DNA matches to Archives’ records, read Debra’s post detailing her success.

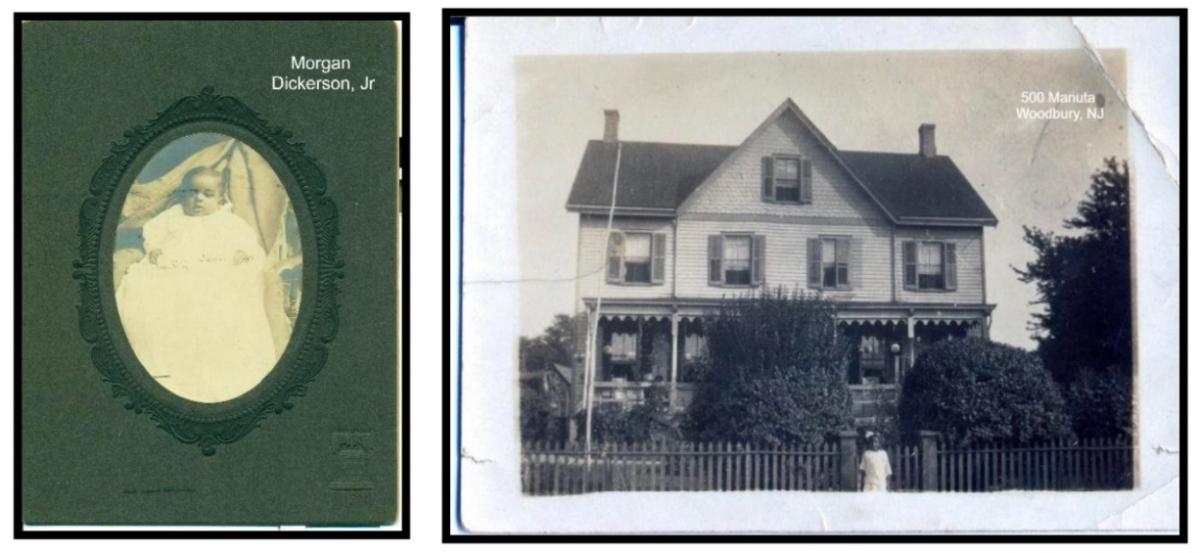

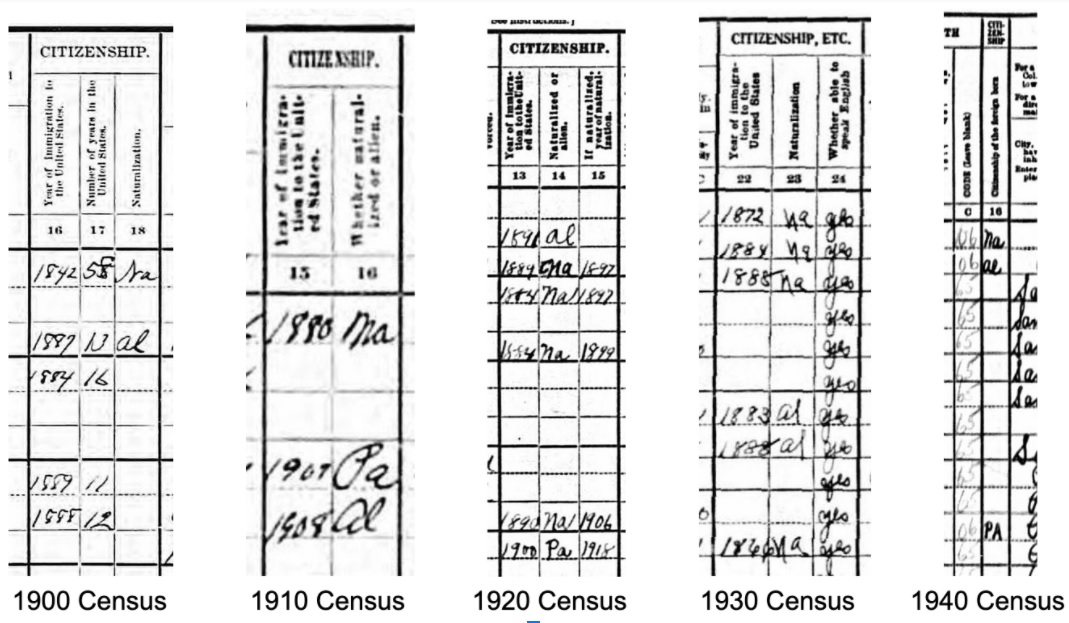

In another very enlightening blog post, Rebecca Crawford, Supervisory Archivist with the Accessioning and Basic Processing Unit at the National Archives at College Park, explains how she used an address written on the back of an otherwise unidentified family photograph to help lead her to census data that revealed information about her husband’s family. Her search started in the 1940 Census, and led her back to 1930…1920…and finally 1910. Though she hasn’t yet been able to identify the name of the young girl in the original photo, she’s been able to go back in time to put together a family tree. What will she find moving forward in the 1950 Census? Stay tuned and follow her story!

from the National

Archives News

Using the U.S. Census to Solve Adoption Mysteries

by Debra Steidel Wall

and

Who Are You? Using the Census to Add Context to Family Photos

by Rebecca Crawford

Morgan Dickerson Jr. (left)

and unknown girl (right)

in front of 500 Manuta

Woodbury, NJ

As an archivist and subject matter expert for immigrant records with the Office of Research Services at the National Archives at Kansas City, Elizabeth Burnes relies on census data to help people start tracking their ancestors’ arrivals and movements in the U.S. She explains the techniques she uses in this blog post. If you need help decoding the arrival statuses of your family members, her blog is the place to go. For further insights from Elizabeth, we are hosting a program with her on April 28th, where she’ll talk about the Immigrant Experience as related to the Census in greater detail!

Exploring Immigrant

Experiences through

Census Records

Thursday, April 28, 2022

at 5:00 pm

Location: Online

…from census to census

What’s In a Name?

Port of New York Passenger Arrival Lists

Source: National Archives at New York City

One of the most frustrating problems genealogists encounter regularly is that the people they are trying to track down have changed their names, and we don’t always know the reason. The professionals who are available to answer your questions on the National Archives’ History Hub, a public research community you can access at are prepared to offer you counsel about how to deal with this.

Source: History Hub Genealogy discussion

NUMIDENT Search Tool

Source: History Hub Immigration and Naturalization Records discussion

Sometimes, people who immigrated to the U.S. “Americanized” their names after they arrived to help themselves fit into the community better. You can check out NARA’s records of passenger arrival lists at various immigration ports here. Women often changed their names when they married. But on occasion, the reasons for changing one’s name were more bureaucratic, or even mysterious. Although legal name changes are usually handled through state agencies, the National Archives does have resources that genealogists can peruse. This user is looking for records regarding his father’s legal name change, and was given the gateway to the Numerical Identification Files, documenting name changes between 1936-2007. If you have questions about a name change, ask on History Hub!

Counting Reservations

One of the most interesting facts about the 1950 census is that it was one of the first national efforts to thoroughly count Native Americans on reservations. The U.S. Constitution excluded “Indians not taxed” from being counted, and confusion about what that language exactly meant resulted in Indians either not being identified as Native or not being counted at all in the decennial censuses from 1790 until the mid-nineteenth century.

Sioux Reservation at Fort Peck Indian Agency

on January 12, 1881

By 1890, however, the new Census Act required that Indians be counted, and the difficult work of enumerating them on the reservations began. From then until 1950, data about Native populations on reservations were collected with varying degrees of accuracy. For the 1950 census, a new form, the P8 Schedule, was drawn up specifically for use on reservations, and census takers were trained in how to use it.

As Archivist and Subject Matter Expert for Native American Related Records at the National Archives Cody White explains in “The Story of the 1950 Census P8 Indian Reservation Schedule,” Schedule P8 was developed for a rather more sinister purpose than just gathering routine information about how many Native Americans were living on the reservations. Counting Natives on reservations vs. off reservations allowed policymakers to discern the rate at which Natives were “assimilating” to white American culture. The Census Bureau documents the policy of “termination”, a popular view in the 1940s that took assimilation to the extreme of involuntary “assimilation” through terminating the recognition of specific nations or reservations.

in NARA’s Text Message blog

Census takers still encountered obstacles in counting Native populations in 1950. Namely, many Native peoples did not have official birth certificates, used many different names, held superstitions about speaking certain names, or were so spread out that an individual Census taker could not cover the entire reservation.

For an in-depth dive into the fascinating story of the P8 Schedule in the 1950 census, check out the blog post at The Text Message.

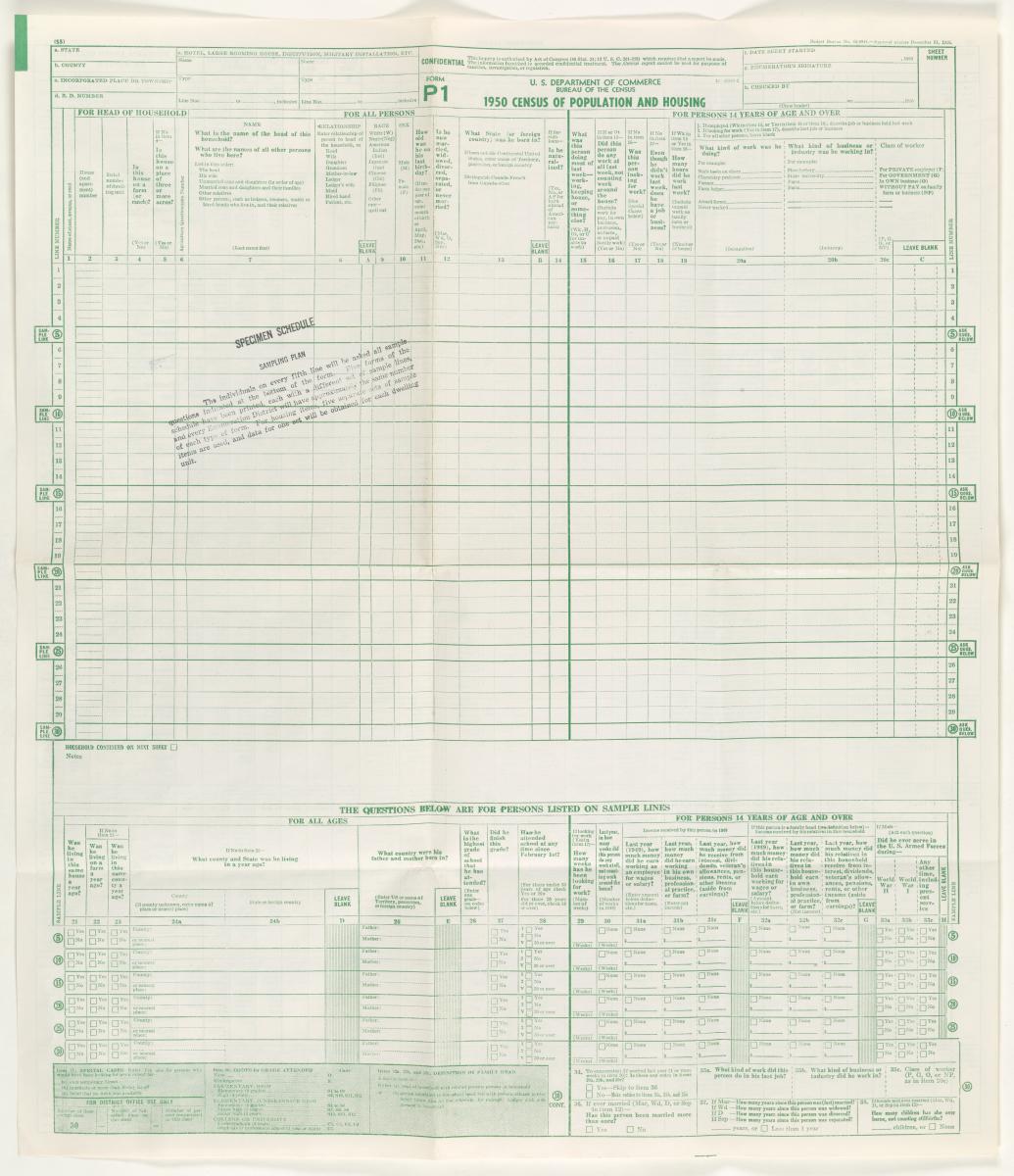

Census Forms: Never Used!

1950 Census forms

If you’re curious about what sorts of information that census takers gathered for the 1950 census, the National Archives has posted many of the blank forms that they used. Besides Form P1—Census of Population and Housing and Form P2—Individual Census Report, specialized forms were used to accumulate data American Samoa, Guam, Alaska, Hawaii, the Panama Canal Zone, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Check out the complete list of forms here. Looking for a fun activity? See if you can fill out this form for your own family!

The Big Count

In the run-up to the decennial census, the U.S. Census Bureau prepares many different materials for different purposes. In addition to data from the census itself, the National Archives is also the repository for those materials.

(3 minutes 46 seconds)

National Archives Identifier: 208383217

National Archives Identifier: 178688266

Image 29-FS-1950-1-1

National Archives Identifier: 206240455

With the release of the information of the 1950 census, the National Archives now also has public service announcements that ran on television to notify the public about the upcoming census and what to expect. The Archives also holds the Census Bureau’s detailed training materials that census takers studied before they took to the streets to count all Americans. “The Big Count” is a filmstrip that explains why the census is taken every ten years and how and what kind of information is gathered. Take a look–many of the illustrations are quite entertaining.

Finally, the bureau prepared “We Count in 1950,” a handbook for U.S. secondary school teachers to use to explore the subject of the census with their students.

Census programming is made possible in part by the National Archives Foundation through the generous support of Denise Gwyn Ferguson.