Myth: Busted!

What does January being National Bathtub Safety Month have to do with this week’s newsletter? This obscure designation instantly brought to mind President William Howard Taft’s bathtub fiasco. As the “story” goes, President Taft was finishing up a bath when, due to his size, he was unable to get out of his White House bathtub – he was stuck. Can you imagine this story breaking on social media today?

The Taft tale is just that – a legend. So that raises the question: what other popular and often-repeated “facts” about American history are also myths? Surprisingly, there are a lot of them! And while some misconceptions are harmless, other incorrect, persistent narratives warp our understanding of American history and can even negatively affect the present.

Luckily, the Archives has the documents to set the record straight. Read on!

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

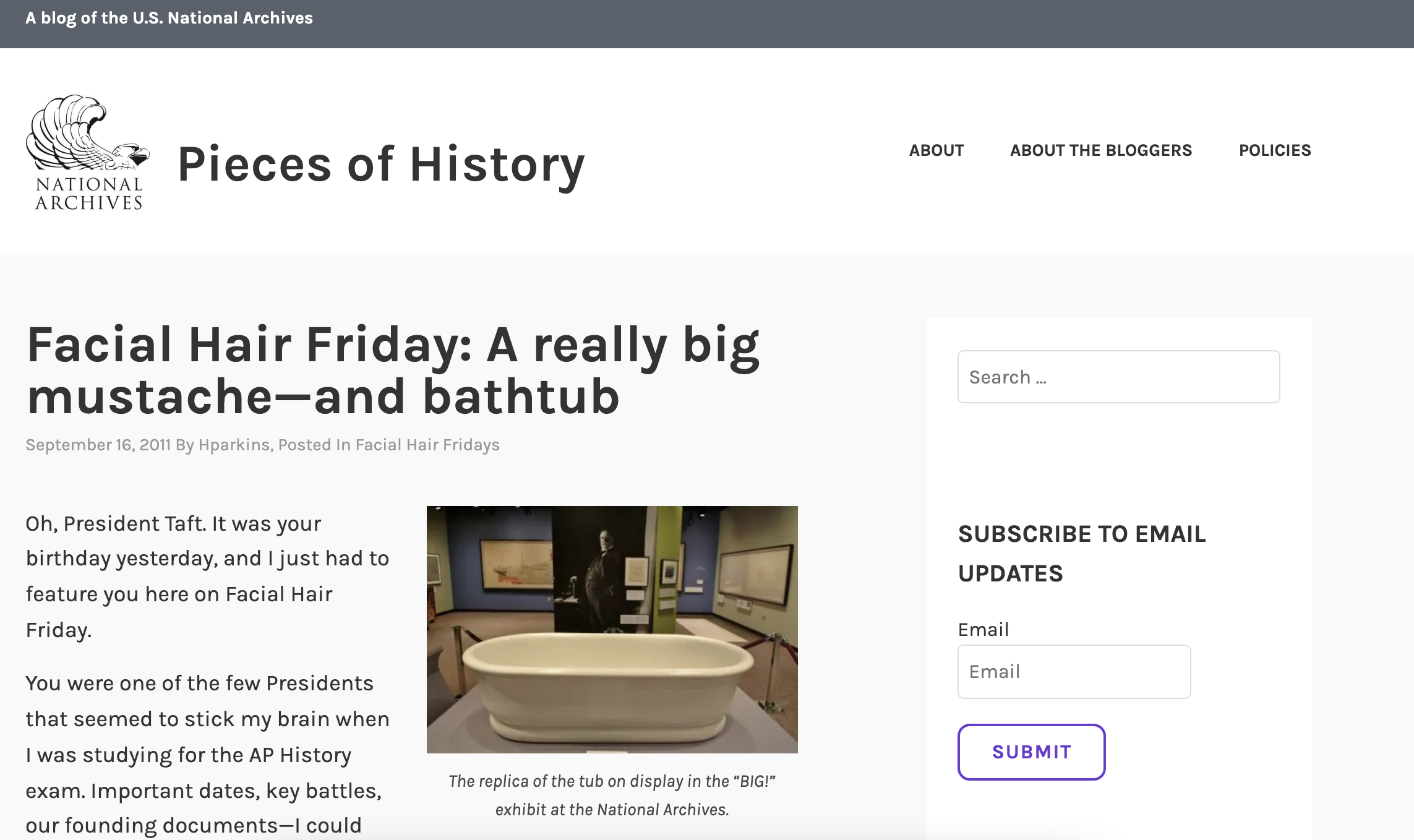

The Bathtub Blunder

in the Archives’ Prologue Blog

William Howard Taft is one of our most accomplished Presidents. Having served as the nation’s highest elected official from 1909 until 1913, he then taught law at Yale University, his alma mater, until 1920, when President William G. Harding nominated him to the Supreme Court. That was, in truth, the job Taft really wanted, and he excelled at it.

However, what many people immediately remember about Taft is the persistent rumor that he got stuck in the bathtub in the White House. Taft was a big man, standing about six feet tall and weighing more than 300 pounds while he was in office. And there is a story about Taft and a bathtub, but the good news is, he didn’t get stuck in one.

Shortly after he was elected president, Taft needed to travel to Panama to inspect progress on the Panama Canal. Prior to the trip, he had a bathtub custom built and installed for himself in the USS North Carolina. The tub measured 7 feet 1 inch long and 41 inches wide and weighed one ton.

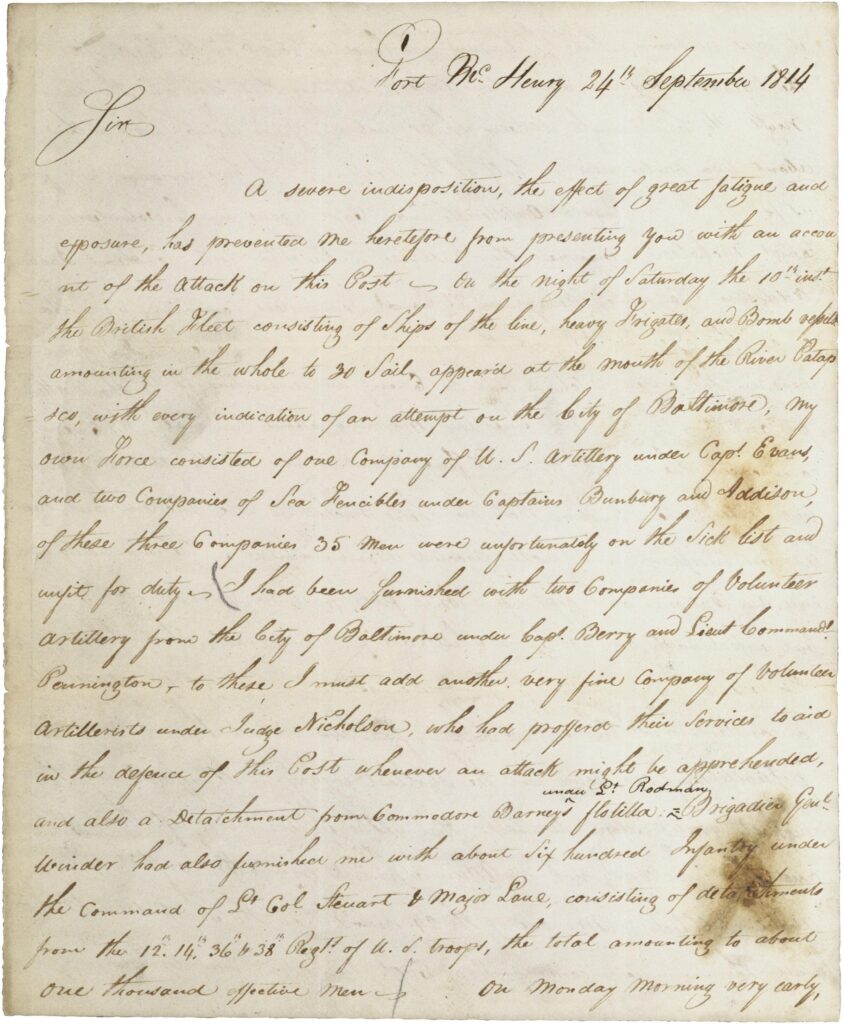

Sounds Familiar

on the defense of Fort McHenry, September 24, 1814; Records of the Office of the Secretary of War; Record Group 107; National Archives

“The Star-Spangled Banner” has been the national anthem of the United States since Congress made it official in 1931. Francis Scott Key, an American lawyer and poet, wrote the lyrics of the anthem after he witnessed the bombardment of Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor in September 1814, the second year of the war of 1812 with Britain. Key was inspired to write the poem, which he titled “The Defence of Fort MHenry,” by the sight of the American flag still flying over the fort after the night-long battle.

from the Office of the Federal Register (OFR)

Thus, the words are decidedly of American origin, but the tune is a different matter. At the end of September, the Baltimore Patriot and The American newspapers both printed the poem and included a note that the tune was “Anacreon in Heaven,” or more accurately, “The Anacreontic Song,” which was written for a gentlemen’s club in London. The tune was popular in the United States at the time and soon became the accepted musical framework for the anthem.

Another interesting fact that is not immediately apparent when the song is played nowadays is that “The Star-Spangled Banner” is a waltz, written in three-quarter time, as anyone who reads music can confirm.

The Far Reach of Slavery

Another common misconception is that slavery was practiced only in the Southern United States. It is true that the importation of slaves was abolished by act of Congress in 1808, but of course, that did not end the practice in the country. The population of enslaved persons in the U.S. continued to grow after 1808 by natural increase. Furthermore, slavery was widespread in the North as well as the South. Plantations situated on major northern rivers like the Hudson, the Connecticut, and the Delaware ran on and profited from enslaved labor.

in Prologue Magazine

Slavery was a prominent facet of life in Washington, D.C., as well. Because of its strategic location between Maryland and Virginia, the district was a prime location for the buying and selling of enslaved people. Traders within the city were also notorious for the practice of housing slaves in crowded pens and prisons and using “slave-coffles,” long lines of humans shackled to one another. These inhumane practices drew nationwide criticism and shame to the nation’s capital.

in the Archives’ Pieces of History blog

Although the city of D.C. banned the slave trade before the Civil War, it did not ban slavery itself, and the burden was on free Blacks to prove their status by constantly carrying certificates of freedom. Even after slavery was banned in D.C. in 1862, President Lincoln primarily supported a controversial recolonization process that would send Black residents back to Liberia, Haiti, or the Chiriqui Islands or would even confine them to Texas.

We Cannot Perpetuate a Lie

Of all the famous stories about George Washington, the tale about how he refused to lie to his father about having chopped down a precious cherry tree might be the most often repeated. However, the story was actually made up in its entirety by Mason Locke Weems, a minister who published the first biography of the first President one year after Washington’s death in 1799. Weems’ The Life of Washington is a masterwork of overblown rhetoric and invented tales, among which the cherry-tree incident is one of the most prominent.

Johnny Appleseed

The popular image of Johnny Appleseed is of a barefooted wanderer who traveled the early United States, planting apple trees here and there and moving on. Some even question whether he existed at all. But John Chapman, also known as “Johnny Appleseed,” did in fact live, and he was rather more complicated than the better-known tale suggests.

Grave of John Chapman

for the Johnny Appleseed Memorial Park in Fort Wayne, which was indoctrinated in 1973

Chapman was born in 1774 in Leominister, Massachusetts, and died and was buried in Fort Wayne, Indiana, in 1845. Clearly, during his lifetime, he covered a lot of territory. He got his start as a nurseryman when, as a young man, he apprenticed with a Mr. Crawford, an orchardist who taught him about caring for trees and who sparked Chapman’s lifelong passion for apple trees. Chapman moved from place to place, planting nurseries (not individual apple trees) and leaving them in the care of local farmers.

Chapman was eccentric, to say the least. He was a pacifist, a vegetarian, a lover of animals, and a devoted follower of the Swedish theologian Emanuel Swedenborg. His clothing was often ragged or missing altogether. He dedicated his life to planting apple trees and preaching the teachings of Swedenborg’s New Church.