The Memory Game

The Memory Game

We have had forty-six Presidents – how many can you name? Certainly, most of us could make a run at the presidents during the period of our country’s founding. Of course, most know Lincoln, who gave the country the Emancipation Proclamation, and FDR, who led us into World War II and is the only four-term president. But who was in the White House during the Spanish American War or when the twentieth amendment was passed? Unless you are prepping for an AP U.S. history exam, more than a few probably escape you. That’s where we come in.

The National Archives is home to all records of the Executive Office, keeping track of the Presidents and their achievements great and small. Don’t forget that the Archives runs the modern Presidential Libraries, starting with Herbert Hoover. We’ve been highlighting those presidential library museums and archives in our virtual programs.

This week, refresh your memory as we take a look at the legacies of a few oft-forgotten presidents. While their names may be forgotten, their impact on our country’s history cannot be.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

The Little Magician

The eighth President of the United States is one of the least remarked-upon men to have ever held the office. Born in Kinderhook, New York, in upstate New York, to Abraham Van Buren, a prosperous businessman and tavern owner of Dutch descent, and Maria Hoes Van Alen, a widow also of Dutch extraction who had three children by her first husband, Martin Van Buren was the middle of the couple’s five children. He holds the distinction of being the only President who spoke English as his second language, his first being Dutch.

Jackson’s nomination of Van Buren for Secretary of State

Nicknamed “the Little Magician” for his short stature (he was 5’6″ tall) and his ability to work with people with many different viewpoints, Van Buren was active in local politics at least by the time he was eighteen, if not before that. He served in the New York Senate from 1813 until 1820 and concurrently as the New York Attorney General from 1815 until 1819. He then was elected Senator for New York and served two terms before he became the governor of the state, serving a two-year term.

In 1829, President Andrew Jackson asked Van Buren to become his Secretary of State. Van Buren accepted, but the experience was rife with drama and controversy. Vice President John C. Calhoun had convinced Jackson to appoint several men to the cabinet who were loyal to Calhoun rather than Jackson. The end result was that Van Buren resigned his position, but Jackson kept him on as a member of his Kitchen Cabinet.

In 1832, Jackson rewarded Van Buren for his loyalty by choosing him instead of Calhoun as his Vice Presidential nominee. The two were elected in a landslide and served two terms.

in Pieces of History

Van Buren was elected to the presidency in his own right in 1836. In 1837, an introductory letter from the new Queen Victoria began a prolific written relationship between the two. But his tenure was also plagued by serious problems. Not long after his inauguration, the panic of 1837 plunged the country into a protracted economic depression. Van Buren tried several measures, including cutting federal spending drastically, but nothing really helped prop up the failing economy. Furthermore, the Indian removal practices that Jackson had instigated and Van Buren pursued ignited the Second Seminole War in Florida, the longest and most expensive Indian war in the nation’s history.

Martin Van Buren lost his bid for a second presidential term. He returned to Kinderhook, where he devoted himself increasingly to antislavery activities. During the Civil War, he supported Abraham Lincoln. Van Buren died in 1862.

Old Rough and Ready

Mexican-American war flag, presented by the Ladies of Fayetteville, N.C. as a tribute to the first volunteer company raised during the Mexican-American War

Zachary Taylor, the twelfth President, is mainly remembered because he died just sixteen months after he took the oath of office. In that short span of time, his administration accomplished very little.

Prior to his election, Taylor had made a name for himself as a successful soldier. He was born in Virginia in 1784, but his family moved to Louisville, Kentucky, when Taylor was still a child. In 1808, he joined the army and was commissioned as a first lieutenant. He served at various posts and in various capacities over the next several years, married and started a family, and resigned his commission and rejoined the army on several occasions.

from the Trump White House’s history archive

Taylor reached his apex as a military commander during the U.S.-Mexican War (1845–1848), which resulted in the Mexican government relinquishing to the United States territories that include what are now the states of Texas, New Mexico, Alta California, Utah, and Nevada and parts of Wyoming, Colorado, Kansas, and Oklahoma. Promoted to major general and flush with this success, Taylor ran for President and was elected in 1848.

The Reluctant POTUS

Massachusetts delegates’ certification of election of Garfield/Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur was a Vice President who really didn’t want to become President, and he most certainly didn’t want the job the way he got it. Arthur and President James A. Garfield had been in office less than four months when Charles J. Guiteau shot Garfield at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington, D.C., on July 2, 1881, as Garfield was preparing to catch a train to go on vacation. Carried from the train station to the White House, Garfield at first rallied, but the wound in his back became infected. He lived for seventy-nine days after he was shot and died on September 19, 1881.

Many of his contemporaries, including Mark Twain, considered Arthur a good President, but he was not particularly effectual at dealing with national problems such as decreasing the national deficit. Suffering from poor health, he did not seek reelection in 1884.

Forgotten Vice Presidents

It might seem that Vice Presidents are inherently forgettable—once in office, they sometimes seem to fade into the woodwork. But on occasion, Vice Presidents were missing for just that reason—nobody was at work in the Vice President’s office.

This document outlines the etiquette of using the Presidential and Vice Presidential Seals

For various reasons, several Presidents have not had Vice Presidents for stretches of their terms, but four have had no Vice President at all: John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Andrew Johnson, and Chester A. Arthur. In all four cases, these men ascended to the office after the President died in office.

For the Vice Presidents that DID exist, did you know that the National Archives preserves Vice Presidential records as well? You can research three of our more modern VPs in the Archives, Al Gore, Dick Cheney, and now-President Joe Biden.

The Elephant and the Donkey and…the Bull-Moose?

The Republican and Democratic Parties have been in power for so long that it’s easy to forget that many other political parties have come and gone in the past 240-plus years. The original political party was the Federalist party, established by contemporary cultural hero Alexander Hamilton in 1789. The opposition party was the Anti-Federalists. The Federalists nominated its last candidate in a presidential election in 1813 and was dissolved in 1835.

in America’s Founding Documents

Along with the Democratic Party, the Whigs was the other major political party in the mid-1800s. The party was founded in 1833, mostly as an opposition party to the policies of Andrew Jackson, who was elected President in 1829. Favoring rapid industrialization and economic growth, a national banking system, and high tariffs, the Whigs clashed repeatedly with the Jackson administration. The party was dissolved in 1856.

Source: NHPRC

Former President Theodore Roosevelt founded the Progressive Party, also called the Bull-Moose Party, in 1912 after he lost the Republican nomination for President to William Howard Taft. The party survived a mere eight years, after which it merged with the Republican party, from which it had split in the first place.

The Lost Gift Stones of the Washington Monument

in Pieces of History

The Know Nothing Party (also known as the Native American Party) was founded in 1844. Its members called themselves “Native Americans” because they were opposed to the practice of the Roman Catholic religion in the United States, and consequently, they opposed the immigration of Roman Catholics from countries like Italy and Ireland. Despite that unmistakable bigotry, the party supported labor rights, women’s rights, regulation of industry, improved conditions for working people, and increased government spending. It was neutral on the issue of slavery, which stance largely led to its demise in the fevered run-up to the Civil War, when the Republican and Democratic Parties were taking most decided stances on the issue. Before the party collapsed, however, some of its members stole a stone Pope Pius IX had given the nation in 1854 to be built into the wall of the Washington Monument.

Source: Prologue Magazine

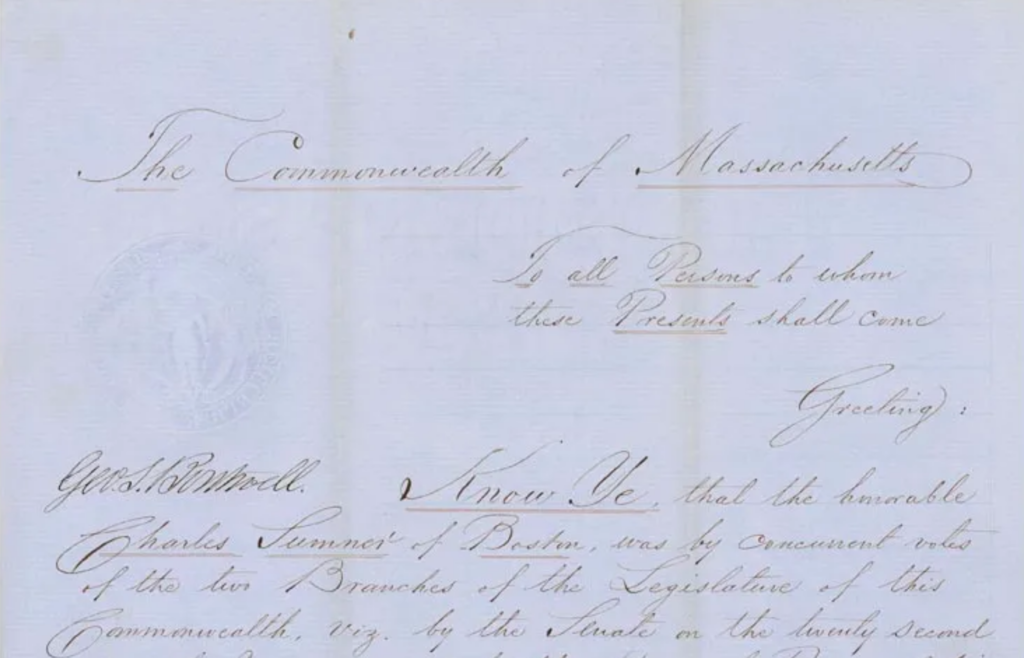

The Free Soil Party lived an even shorter life, being founded in 1844 and dissolved in 1854. The party opposed the expansion of slavery into the western territories of the United States, an unresolved issue that greatly contributed to the outbreak of the Civil War. One of the few Free Soilers elected to Congress was Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, who made every effort in his power to end slavery.