Archives Experience Newsletter - January 31, 2023

It’s Cold In Here

It’s the dead of winter–the kind of weather that makes you want to sit by a cozy fire with your favorite book and a hot drink. But here at the Foundation, we’re bundling up to go exploring, and we’ll need more than a set of matching hats and mittens for where we’re going. Don’t worry, you can join us from the comfort of your email inbox.

This trip takes us to the end of the world…the South Pole to be exact. Known for its remoteness, harsh climate, and of course, penguins. The South Pole has been a literal magnet for explorers and adventurers throughout history. Today, we’re taking a look at the records of history’s greatest polar pioneers and the discoveries they made through tragedy and triumph.

In this issue

The oldest object in the National Archives Cartographic collection is the Polus Antarcticus map of Antarctica…

The Heroic Era

On January 17, 1773, on his second scientific voyage on behalf of the Royal Society, Captain James Cook crossed the Antarctic Circle…

The Mechanical Era

The most prominent Antarctic explorer of the mechanical era of Antarctic exploration was doubtless Admiral Richard E. Byrd…

History Snack

Igloo traveled to both the North and South Poles on expeditions with Admiral Byrd…

Polaris

The oldest object in the National Archives Cartographic collection is the Polus Antarcticus map of Antarctica, one of the first depictions of Earth’s southernmost continent. Published sometime after the 1640s, when the Dutch navigator Abel Tasman first reached Tasmania and New Zealand, this map shows a rather vague outline of Antarctica and is adorned with drawings of penguins, hunting scenes and native peoples around its edges.

Polaris Antarcticus map (oldest in cartographic collection)

Source: NARA’s The Unwritten Record blog

Cropped section from the bottom right of the Polaris map

Source: NARA’s The Unwritten Record blog

A The Heroic Era

Antarctic Region

National Archives Identifier: 266783409

On January 17, 1773, on his second scientific voyage on behalf of the Royal Society, Captain James Cook crossed the Antarctic Circle for the first time with his two ships, the HMS Resolute and the HMS Adventure. The two vessels were soon surrounded by fog, and Tobias Furneaux, who commanded the Adventure, turned back to New Zealand. Cook continued on toward the Antarctic continent, but before he reached the mainland, he ran short of supplies and returned to Tahiti to restock. Besides his achievement in crossing the circle first, his main contribution to Antarctic exploration was his contention that any landmass that far south would be useless for economic development. His opinion was so valued that exploration came to a screeching halt for nearly 50 years.

From 1819 through 1843, various explorers began to investigate the perimeters of Antarctica. In 1819-1821, Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Lazarev circumnavigated the continent, and in 1840, Charles Wilkes discovered Victoria Land and named the volcanoes now known as Mount Terror and Mount Erebus in 1840. In 1839-1841, James Clark Ross led a scientific expedition aboard the ships HMS Erebus and HMS Terror to Antarctica that resulted in significant geological and botanical discoveries, but in January 1841, Clark affirmed Cook’s contention that there was no compelling economic reason to try to explore the continent.

Antarctica Map

National Archives Identifier: 266783163

Upon the expedition’s return, the Erebus and the Terror were refitted for Sir John Franklin’s ill-fated Arctic expedition that departed England in 1845 in search of the Northwest Passage. That expedition was last heard from in July 1845; all 129 hands, including officers and sailors, disappeared into the Arctic wilderness. Many search parties, over sea and over land, some launched by the British government and some paid for privately by Jane, Lady Franklin, looked for survivors throughout the next decade. They eventually turned up some items from the ships, a handful of personal possessions belonging to some of the sailors and two bodies that were sent back to England. The sad fate of the Franklin expedition dampened the public’s appetite for Arctic and Antarctic exploration for a time, as did the distractions of the 1848 revolutions in Europe and the Civil War in the United States.

By the end of the 19th century, however, the “heroic age of Antarctic exploration” got underway, so-called to distinguish it from the “mechanical” age that followed, when innovations such as aircraft somewhat lessened the difficulties inherent in exploring polar regions.

In any era, exploring Antarctica is not for the fainthearted. The climate is extremely cold and dry. Along the coast during the winter, the temperature can range from 14° to -22°F, while during the summer, it usually ranges from 32°F to a sweltering 48°F. The interior is much colder, dipping below -76°F in winter and -4°F in summer. All precipitation in Antarctica falls as snow and amounts to only two to four inches of water every year. The polar winds that blow there are epic, whipping up the snow into whiteout conditions.

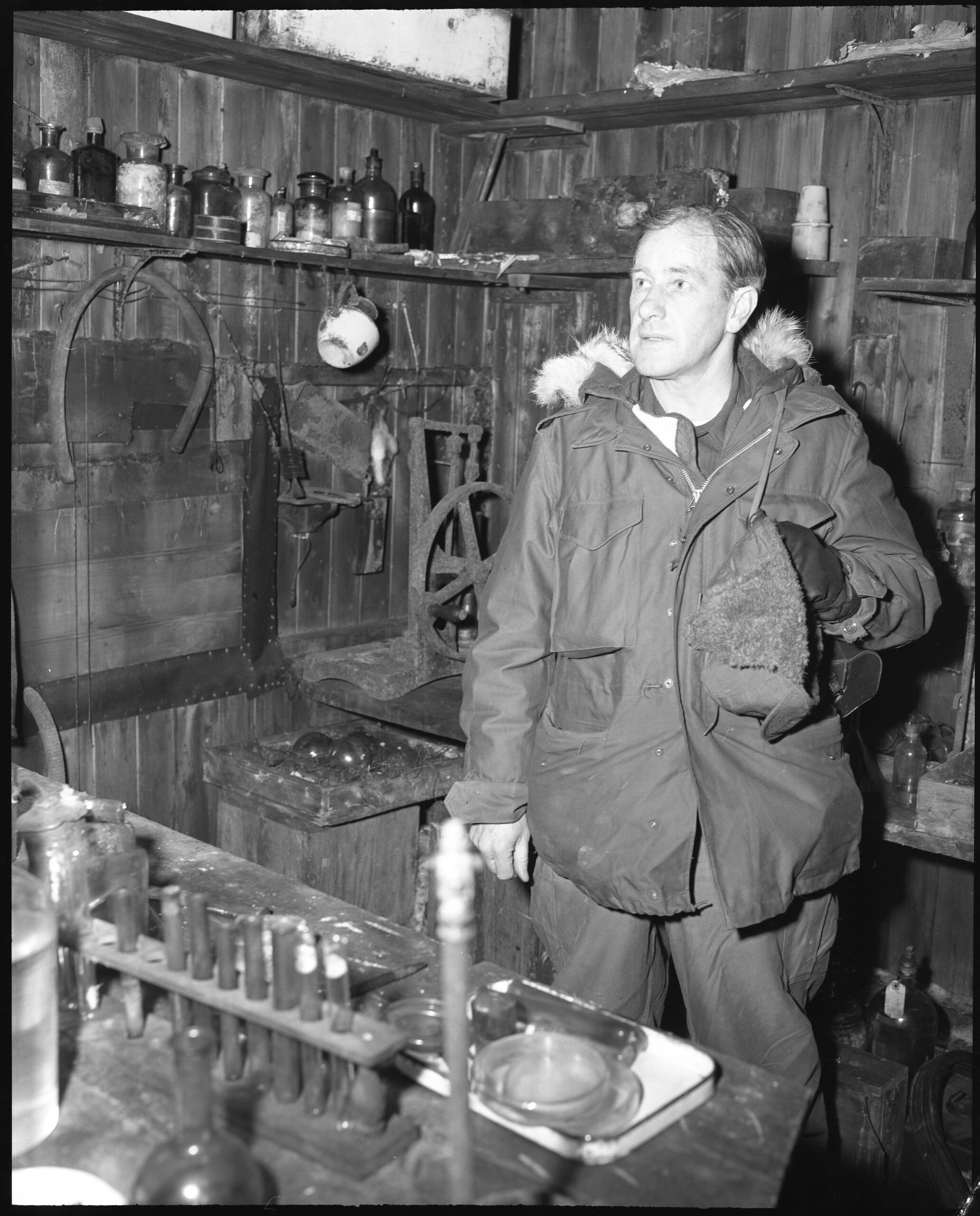

Although between 1897 and 1922, nearly 20 expeditions traveled to Antarctica from all over the world, including Belgian, France, Germany, Norway, Sweden, Australia and New Zealand and Japan, by the middle of the century, the great trifecta of explorers was the Norwegian Roald Amundsen and two Brits, Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton. Between them, they led a total of six missions to the southernmost continent, set multiple records for southward travel and mapped vast expanses of the interior and the coastlines.

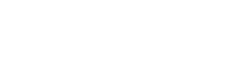

Remains of the Robert Scott hut at Cape Evans– pictured is Sidney Nolan

National Archives Identifier: 148728330

Roald Amundsen, a Norwegian explorer whose first venture south had been as first mate on the Belgian Antarctic Expedition commanded by Adrien de Gerlache on the Belgica in 1897-1899, came to Antarctica supplied not only with men and materials, but also with dogs to pull his sledges, which set his expeditions apart from the British, who scorned such advantages in favor of “man-hauling”—tethering themselves to sledges loaded with all their supplies and then pulling them behind them on overland treks. The early goal of Antarctic explorers was to be the first to reach the South Pole. Shackleton led the charge in 1907-1909. Commanding the Nimrod, he led a march southward that fell just 97 miles short of his goal. Then in 1910-1913, Admundsen and Scott engaged in what became a deadly competition to reach the South Pole. Admundsen and his team of five won that race by 33 days, reaching the pole on December 14, 1912. Scott and his four companions reached the South Pole on January 17, 1913, but were waylaid by bad weather and starvation. All five perished on their return trip to Hut Point.

Cigarette trading card of Roald Amundsen

National Archives Identifier: 165318347

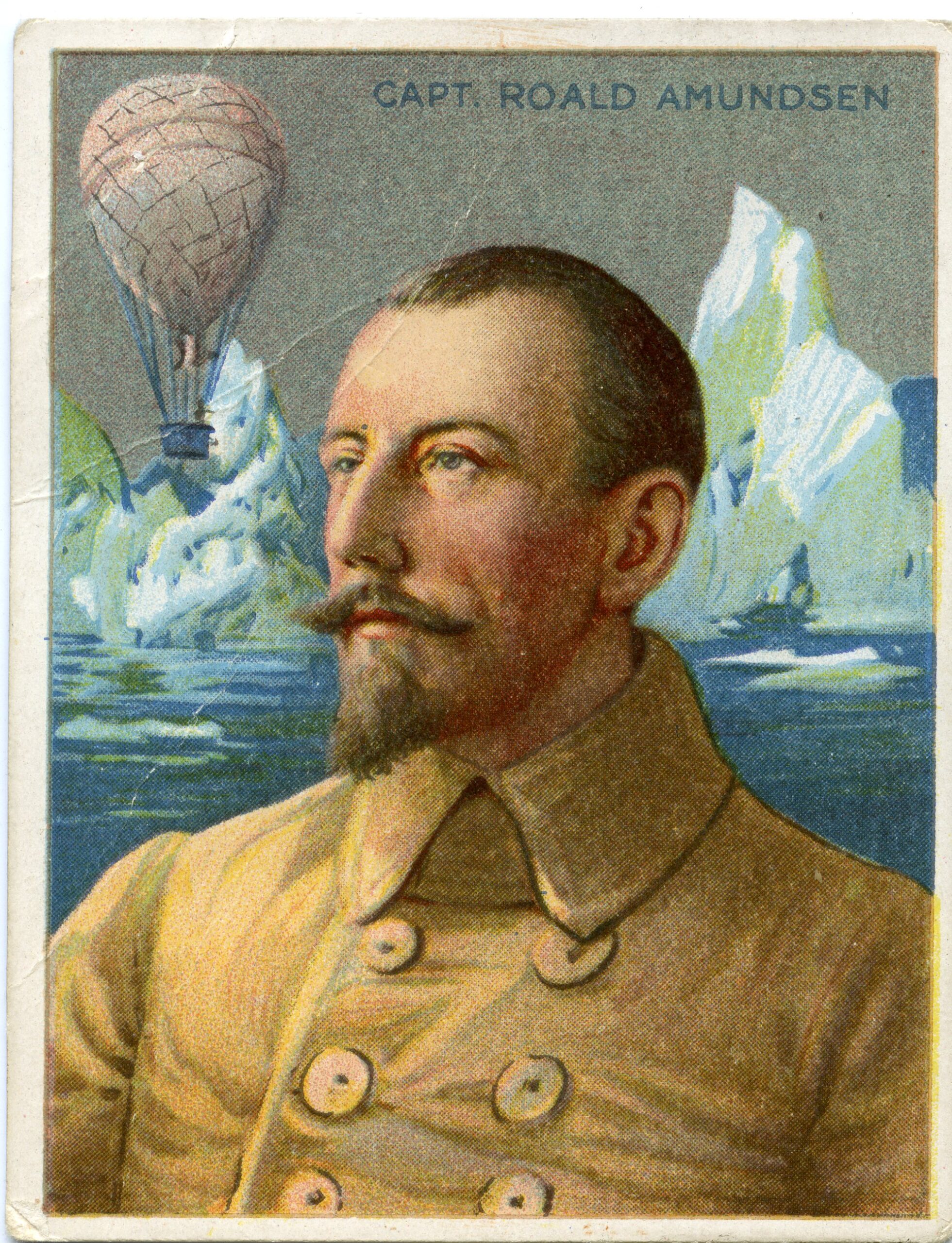

On January 11, 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, joined by heads of state from Norway, the United Kingdom and New Zealand, dedicated the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, a permanent observatory and work station at the South Pole, in honor of the Antarctica endeavor of the International Geophysical Year. It is named, naturally, for the two great explorers who competed to reach the South Pole first. The station, which is held under U.S. jurisdiction but not sovereignty, has been continuously inhabited by American scientists and support personnel ever since.

Robert Falcon Scott Discovery Campground

National Archives Identifier: 6442714/figcaption>

Shackleton went back to the Antarctic twice more, first in 1914, with the intention of crossing the continent, but his ship, the Endurance, became trapped in pack ice and slowly drifted north toward the open sea. When the Endurance was finally crushed in the ice, Shackleton ordered his men into the ship’s lifeboats and they set sail for Elephant Island, a journey that took five days across 60 miles of ice-clogged waters. Once there, Shackleton and five men sailed off in one of the lifeboats, the rechristened James Caird, for South Georgia Island, 800 miles away across one of the roughest stretches of water in the world. Having reached South Georgia after what is now called one of the greatest open-boat journeys of all time, Shackleton and his men secured help from those stationed at the Stromness whaling station. Bad weather and the ice pack hindered Shackleton’s efforts to rescue the rest of his crew, but after three months, he sailed up to Elephant Island on the Chilean ship Yelcho and took them aboard. He had not lost a single man.

Dedication of Amundsen-Scott station remarks by Eisenhower

National Archives Identifier: 16646930

More from the Hoover Heads blog: Ernest Shackleton: A Lesson in Leadership

Source: Hoover Library blog

In 1921-1922, Shackleton, who truly was never at home in the modern world, made one more trip to Antarctica in command of the Shackleton-Rowett Expedition aboard the Quest. On the voyage south, the Quest had engine trouble, so they stopped at South Georgia Island for repairs, where Shackleton died of a heart attack. He was buried there in the Norwegian cemetery at his wife Emily’s request. He was 47 years old.

The Mechanical Era

The most prominent Antarctic explorer of the mechanical era of Antarctic exploration was doubtless Admiral Richard E. Byrd, an American naval officer, winner of the Medal of Honor and leader of five expeditions to the southernmost continent. He also claimed to have been the first to have flown both over the North Pole and the South Pole in an aircraft, although his claim about the North Pole has since been disputed.

Byrd’s Antarctic expeditions spanned nearly three decades, from 1928 until 1956, and incorporated ships, airplanes and dogs to move men and materials. Byrd established a series of base camps named Little America on the Ross Ice Shelf, from which his expeditions maintained continuous contact with the outside world via radio, a most definite improvement over earlier explorations.

Byrd led the First Antarctic Expedition in 1928-1930, the Second Antarctic Expedition in 1934 and the Antarctic Service Expedition in 1939-1940 prior to World War II. After the war, Byrd returned to the Antarctic in command of Operation Highjump (1946-1947) and Operation Deep Freeze I (1955-1956), although he only stayed for a week of the latter expedition. He returned home and died in his sleep just over a year later. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Operation Highjump

(2 minutes 38 seconds)

Source: National Archives YouTube page