Archives Experience Newsletter - February 22, 2022

The Week that Changed the World

February 1st marked the beginning of Lunar New Year, which kicked off a sixteen- day celebration of manifesting good health and fortune. The new year in the Chinese Zodiac has just begun. 2022 is the Year of the Tiger. Those born in this year are ambitious, courageous, and adventurous, and they are always up for a challenge. (As are those readers born in 2010, 1998, 1986, 1974, 1962, 1950, and so on.)

Our 37th president, Richard Nixon, needed all those traits for the mission he was about to undertake. Chinese and American relations had been fraught, from the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 to China’s fall to communism in 1949. For years, both American and Chinese diplomats had exchanged cables in secret, attempting to arrange the first-ever Presidential visit to the People’s Republic. Nixon saw an opportunity – not only to check the power of the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War, but also to establish relations, trade, and a cultural exchange with a new nation.

Yesterday was the 50th anniversary of “Nixon in China,” a trip that is well- documented in the National Archives. This week, you can listen to recordings, look at photos, and watch videos of one of the most risky and consequential diplomatic decisions in the twentieth century. Here, we examine post-visit diplomatic relations with the Chinese people and celebrate Chinese-American culture.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

What Year Is It?

1981

1975

Happy Year of the Tiger! We’re just a little late for the actual Chinese New Year’s Festival, which was celebrated from February 1 through February 15, but the Year of the Tiger will last all year.

1984

1982

Chinese New Year, also called the Spring Festival, is celebrated starting on the first day of the first month of the Chinese calendar, so the date shifts from year to year. During the festival, people visit their relatives and friends, share big meals, exchange red envelopes filled with money, and attend parades where they can see lion and dragon dances, martial arts and acrobatic displays, drumming exhibitions, and fireworks, which, by the way, the Chinese invented.

The festival is observed not only in mainland China, but also in many nations that have substantial Chinese populations, including Singapore, Vietnam, Indonesia, Cambodia, the Philippines, Brunei, Thailand, Myanmar, Malaysia, Mauritius, New Zealand, Australia, Peru, South Africa, several European nations, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States. These celebrations have been well-documented in the Archives. A short film in the Moving Picture and Sound Archives, entitled Chinese New Year Parade (Lion Dance) Saigon, Vietnam, shows a Chinese new year parade in Saigon in 1964. The dance was put on by American servicemembers and shows the Lion Dance involving acrobatics, drums, gongs, and martial arts.

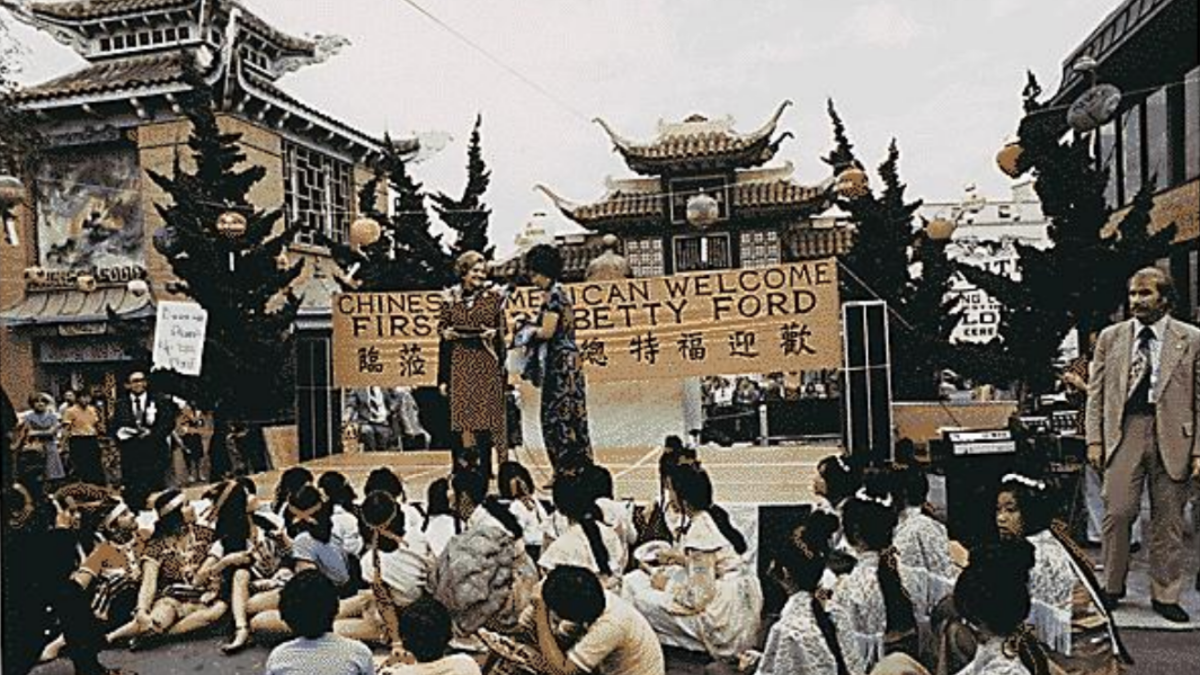

In recognition of that fact, American Presidents have often extended cordial greetings to Chinese Americans on Chinese New Year. You can read New Year’s greetings in full from Presidents Reagan and Ford below.

Chinese new year celebrations

in the Unwritten Record NARA blog

Opening the Door

National Archives Identifier: 6394264

When President Richard Nixon shook hands with Chinese Premier Chou En-Lai on the tarmac at the Peking airport on February 21, 1971, it marked the first official diplomatic contact between the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) since the Communist Party of China took power in 1949. The United States had aligned itself with the defeated Kuomintang (the Chinese Nationalist Party), which had fled the mainland for the island of Taiwan. The U.S. and China effectively shut themselves off from one another at that point.

National Archives Identifier: 194414

However, as time passed, the significance of the People’s Republic on the world stage increased to the point at which other world powers began to realize that they could no longer afford to ignore it. In 1964, the PRC tested its first nuclear weapon, and in 1967, it exploded its first hydrogen bomb. Considering that China had actively intervened in the Korean War in 1950, the United States government had to be seriously concerned that China would likewise in the Vietnam war in Vietnam. As it turned out, China had decided by 1968 not to interfere in that conflict for fear of upsetting the Soviet Union, but that wasn’t known in Washington at that time. Still, by 1971, the population of China had increased to about 830 million, about one-fifth of the world’s population. Such a huge number of people could not easily be ignored.

National Archives Identifier: 6394264

National Archives Identifier: 194428

By the time Nixon became President, PRC Chairman Mao Zedong had decided that the Soviet Union was no longer a reliable ally, and he was looking to improve relations with the U.S. Via backdoor shuttle diplomacy, National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger and Chinese Premier Chou En-Lai met several times in 1971 to negotiate the terms for Nixon’s trip to China. Finally, on July 15, the President announced on live TV that he would be visiting the People’s Republic next year. The next February, he flew with the First Lady and a large press corps to Peking.

The President met with Chairman Mao very shortly after he arrived in China, but only for about an hour. Unbeknownst to the Americans, Mao was not in good health, so Premier En-Lai stood in for him in numerous meetings with the President. President and Mrs. Nixon and their entourage also visited the Great Wall, Shanghai, and Hangzhou. The entire trip lasted a week.

Go in depth with the Nixon Foundation

www.nixonfoundation.org/exhibit/the-opening-of-china

Hear it from Nixon

President Richard Nixon called his 1971 visit to China “the week that changed the world.” For once, his pronouncement was not an overstatement.

In the immediate aftermath of Nixon’s visit, the Chinese and the United States settled their disagreement about Taiwan. Two CIA operatives who had been held captive in China since 1952, John T. Downey and Richard Fecteau, were released after Nixon returned home.

In the past fifty years, the relationship between China and the United States has become one of the most important in the world. In 2021, trade between the U.S. and China, both imports and exports, reached nearly $63 billion.

Of course, not everyone approved of Nixon’s opening up the U.S.’ relationship with China. Five years after the historic visit, James B. Longley, the governor of Maine, wrote President Gerald Ford to caution him about continuing that relationship.

An Issue that’s Black and White

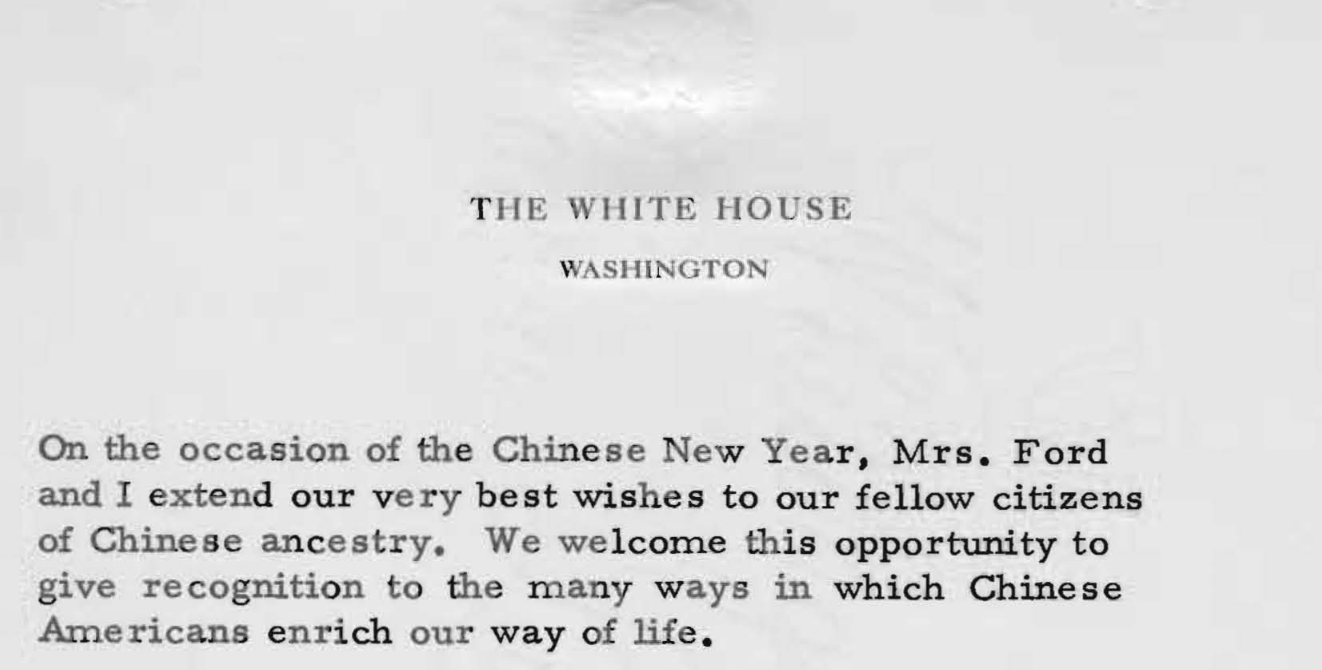

“Panda”monium at the National Zoo

in the Pieces of History NARA blog

Who doesn’t love the pandas at the National Zoo? Every day, hundreds of people flock to watch the black and white bears bask in the sun, loll in their pools, somersault down the hills of their enclosures, and munch on bamboo snacks. They’re too adorable to resist.

But did you know that the pandas are D.C. residents directly because President Richard M. Nixon went to China in 1972? In the tradition of exchanging gifts between heads of state, during his trip, the President presented Chinese Premier Zhou En-Lai with a porcelain statue titled The Bird of Peace that depicted two adult mute swans and several of their chicks. After the President returned home, the Chinese government sent the United States—Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing! First Lady Pat Nixon led the delegation that welcomed the pandas to the U.S. capital.

Come to Dinner

from the Clinton White House

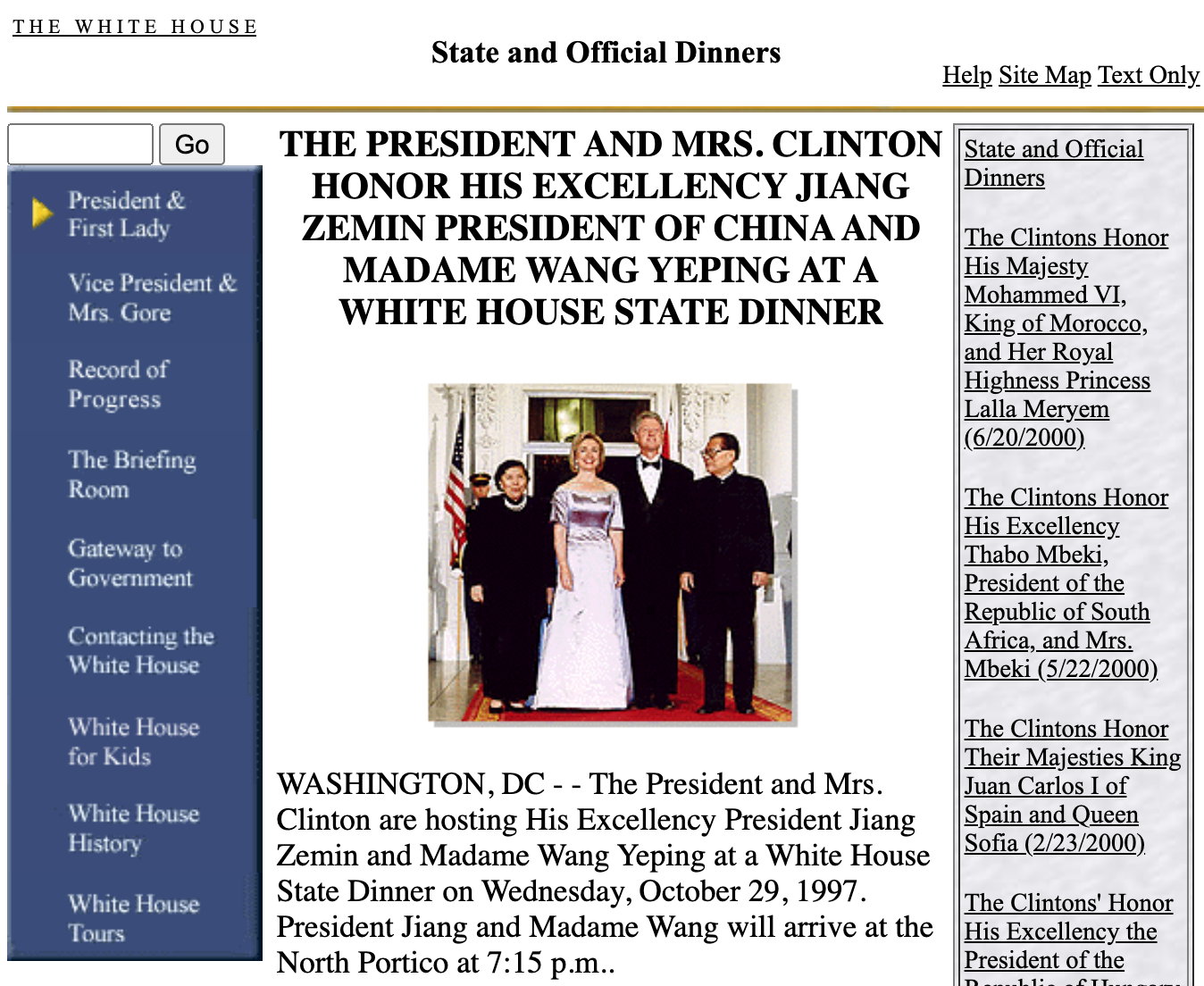

Since President Nixon and Chairman Mao Zedong restored the relationship between the United States and China in 1971, every American President except Jimmy Carter and Joe Biden has visited China, and many Chinese officials have returned the favor. On October 29, 1997, President and Mrs. Clinton hosted Chinese President Jiang Zemin and Madame Wang Yeping at a White House State Dinner in the East Room.

State Dinners at the White House

in NARA’s Pieces of History blog

The dinner menu included American specialties such as lobster, Oregon beef, Yukon gold potatoes, and several California wines. The National Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Leonard Slatkin, performed American musical compositions like George Gershwin’s An American in Paris and John Philip Sousa’s The Stars and Stripes Forever for the guests.