Out-of-this-world Wheels

Do you remember the first time you got behind the wheel of a car? The thrill. The excitement. The nervousness. Now imagine having that feeling on the moon! This week, we celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of NASA dropping a “car” on the moon – AKA, the Lunar Rover.

These days, we have become somewhat familiar with rovers on Mars (and even a Martian helicopter!), but rewind fifty-two years, and nearly all of humankind was watching men land and walk on the moon for the first time. Two years later, NASA wanted to go four-wheeling across the dusty moon surface. (In November 2021, NASA will return to the moon with the unmanned mission Artemis I. Stay tuned for news from NAF about our virtual program coming up later this summer that will discuss this new lunar program and the Apollo mission.)

50th Anniversary of Apollo 15 and the Lunar Roving Vehicle

Boys and girls gazing into a dark starry sky light up their imaginations to explore and wonder what discoveries are possible. Join us this week as we celebrate the space program and the fiftieth anniversary of the moon rover. Also, the Archives is exhibiting documents and photographs related to the Apollo 15 mission. Take a look.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Not-So-Friendly Competition

National Intelligence Estimate:

Soviet Space Programs

Source: Nixon Library

The mission that culminated in the U.S. moon landing was fueled by both fear and competitiveness. On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite, into orbit. Americans were stunned and frightened by this event, fearing that it meant that the Soviet Union might also be able to launch nuclear weapons at the United States and that the U.S. was falling behind the Russians in developing technology. About a month later, the Soviet Union sent Sputnik 2 into space.

Sputnik and the Space Race

Source: Eisenhower Library

The U.S. responded by launching its own satellite, Explorer 1, on February 1, 1958. Over the next three years, both nations launched several more satellites, but then, on April 12, 1961, the Soviets sent Yuri Gagarin into orbit, achieving yet another first and effectively upping the ante. President John F. Kennedy congratulated the Russians on their achievement, but he also announced that the United States intended to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade.

Thus was born the “Space Race,” the competition between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. to gain superiority in space. The United States created the Projects Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo space programs with the goal of putting men on the moon. The U.S.S.R. also intended to explore the moon, but as time passed, the Russian space program veered away from manned spaceflight, instead sending unmanned probes to the lunar surface. The Soviet space program was the subject of ongoing surveillance by the U.S. intelligence agencies throughout the entire decade leading up to the moon landing.

In the end, the astronauts of Apollo 11 became the first men to successfully land on the moon and then return to Earth. The people of the United States were overjoyed by this achievement.

To Boldly Go (Or Not)

Astronaut Edward H. White II’s Space Walk on Gemini IV

National Archives Identifier: 4728365

The recent space flights by Richard Branson and Jeff Bezos have rekindled an old argument about the usefulness of space exploration. Since the very beginnings of the Space Race, critics have questioned the value of such an expensive program. Shouldn’t this government money be spent on Earth-bound problems such as world hunger, disease, and homelessness?

Proclamation 5358 — Space Exploration Day, 1985

Source: Reagan Library

Others argue that exploring space is the next step in humankind’s evolution, a necessary step that will advance knowledge and benefit us all. In his July 20, 1985, Space Exploration Day proclamation, Ronald Reagan addressed this question indirectly, stating, “Space exploration is little more than a quarter century old. In that brief period, more has been learned about the cosmos and our relation to it than in all the preceding centuries combined. The ever-increasing knowledge gained from peaceful space exploration, and the uses to which that knowledge is put, potentially benefit all those aboard Spaceship Earth. The spirit of July 20, 1969, lives on.”

President Barack Obama on Space Exploration in the 21st Century

Source: NASA

President Barack Obama took a more direct approach. In a speech he delivered at the John F. Kennedy Space Center in Merritt Island, Florida, on April 15, 2010, he remarked,

“Now, I’ll close by saying this. I know that some Americans have asked a question that’s particularly apt on Tax Day: Why spend money on NASA at all? Why spend money solving problems in space when we don’t lack for problems to solve here on the ground? And obviously our country is still reeling from the worst economic turmoil we’ve known in generations. We have massive structural deficits that have to be closed in the coming years.

But you and I know this is a false choice. We have to fix our economy. We need to close our deficits. But for pennies on the dollar, the space program has fueled jobs and entire industries. For pennies on the dollar, the space program has improved our lives, advanced our society, strengthened our economy, and inspired generations of Americans. And I have no doubt that NASA can continue to fulfill this role.”

This debate is not likely to be settled anytime soon, especially as the effects of climate change become more evident in our daily lives.

John Glenn at 100

Astronaut John H. Glenn, Jr. in His Mark IV Pressure Suit

National Archives Identifier: 7348582

July 18, 2021, was the centennial of the birth of John Herschel Glenn, Jr., who in 1962 became the first American to orbit the Earth. Glenn was born in Cambridge, Ohio, in 1921. He joined the U.S. Marine Corps after the attack on Pearl Harbor and flew in combat in the Pacific Theater and in the Korean War, completing a total of 149 missions. When the Korean conflict ended, he became a military test pilot. In 1957, he set a speed record for completing the first transcontinental supersonic flight from Los Angeles to New York in three hours and twenty-three minutes.

“God Speed, John Glenn”

Source: NARA’s The Unwritten Record blog

John Glenn was one of the original seven astronauts in Project Mercury, the United States’ first spaceflight program, which was a direct response to the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite. The other Mercury astronauts were Scott Carpenter, Gordon Cooper, Gus Grissom, Wally Schirra, Alan Shepard, and Deke Slayton. Those were heady and terrifying days, days in which the success or failure of a spaceflight meant the difference between life and death for the astronaut. Glenn was the third American to be launched into space and the first to orbit the Earth. He followed Shepard and Grissom, who completed suborbital flights.

With his clean-cut good looks, his all-American upbringing, and his stellar war record, John Glenn became the man of the hour, the face of the U.S. space program, after he splashed down in Friendship 7 in the Atlantic Ocean. But for all his accomplishments, he remained a somewhat reticent hero who was very modest about his contributions to the success of Project Mercury.

Reflections in

History Hub’s

Citizen Archivist blog

After he left NASA in 1964, Glenn entered politics. Following a couple of unsuccessful campaigns, he was elected as a U.S. Senator from Ohio. He served in the Senate from 1974 until 1999. In 1998, he went back into space as a payload specialist aboard the space shuttle Discovery. He was the oldest NASA astronaut and only US Senator to travel to and work in space.

John Glenn met his future wife, Anna Margaret Castor, when they were children. He always called her “Annie.” They married in 1943. They had two children, and they were together for seventy-three years. Glenn died at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus on December 8, 2016. He was ninety-five years old. Annie Glenn passed away in May 2020, of complications due to COVID-19.

Let’s Talk Tech

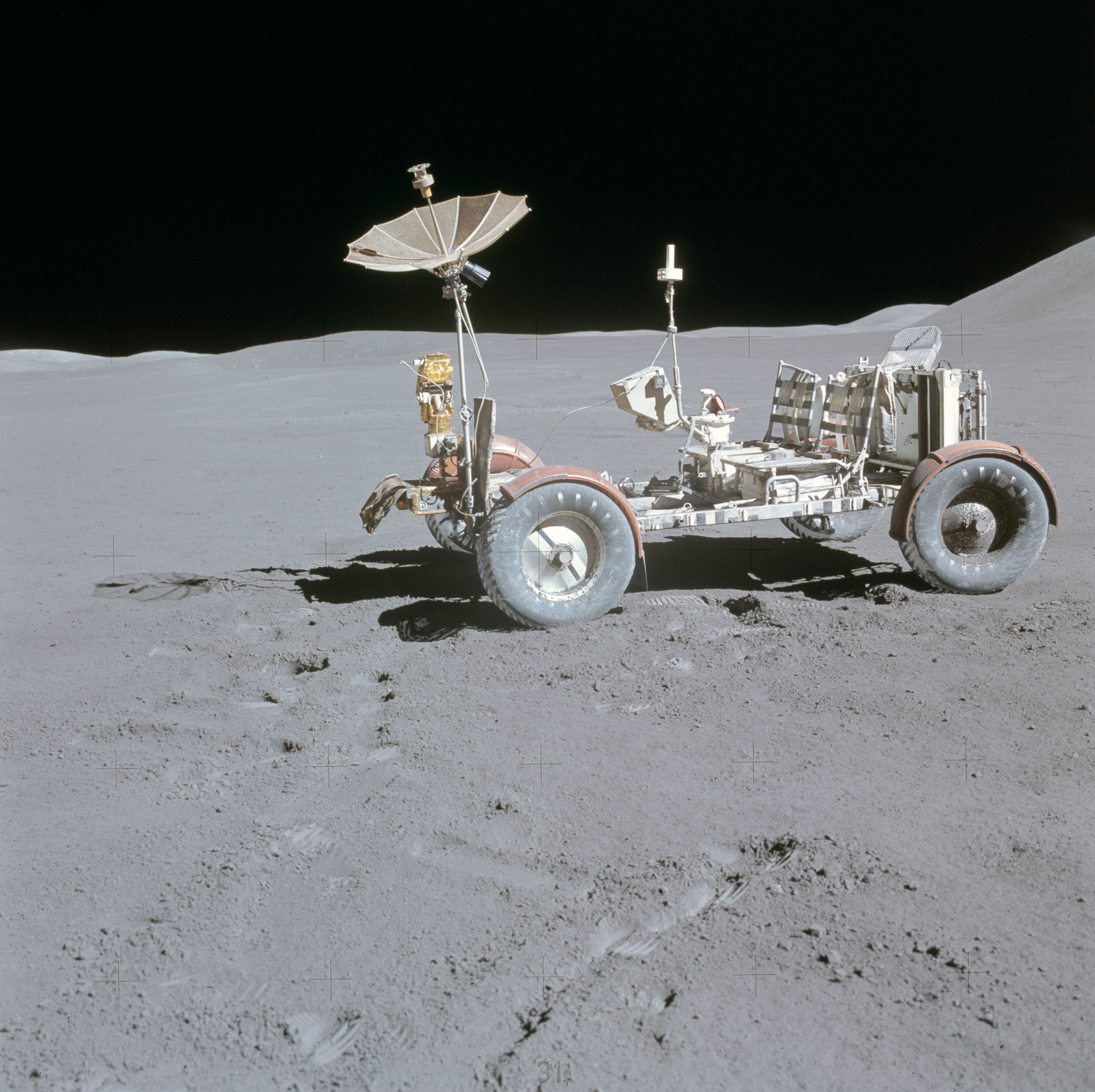

AS15-88-11901 – Apollo 15 – Apollo 15 Mission image – Panoramic of LRV final location, LRV in view

National Archives Identifier: 16705677

Mechanical rovers have both greatly aided space exploration and improved life on Earth for some of our most vulnerable citizens. The Apollo 15 astronauts, David R. Scott and James B. Irwin, were the first to use a Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) to get around on the surface of the moon. Looking rather like a stripped-down dune buggy, the rover was specifically designed to operate on the rocky lunar soil and in low gravity. It enabled the astronauts to travel further from the lunar module and to take more equipment with them. The Apollo 16 and 17 missions also used LRVs.

National Archives Identifier: 81444438

In observance of the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 15 mission, the National Archives is exhibiting an “LRV payload composite view drawing” and several supporting photographs taken on the lunar surface. The Archives is also the repository of materials documenting the mission, including a film of Scott and Irwin outfitted in spacesuits and driving an LRV on a simulated lunar surface, taking samples, working with photographic equipment and hand tools, and then driving the LRV back into the Astronaut Training Building at the Kennedy Space Center.

The LRV is truly the predecessor of the Mars rovers that NASA has deployed to explore the surface of Mars: Sojourner (1997), Opportunity (2004), Spirit (2004), Curiosity (2012), and Perseverance (2021). Back on Earth, the technology developed for LRVs has also been used to create mechanized wheelchairs.

Could YOU Join the Crew?

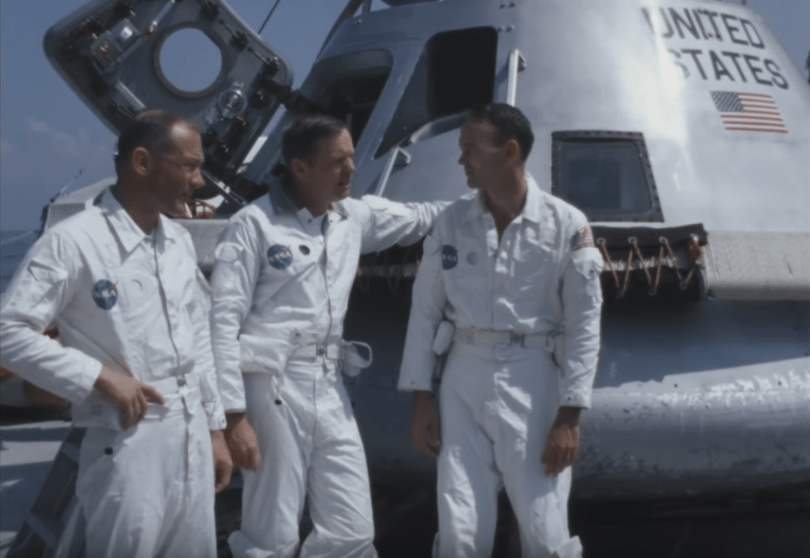

Astronauts Aldrin, Armstrong, and Collins participate in water egress training in the Gulf of Mexico

National Archives Identifier: 81442858

Source: NARA’s The Unwritten Record blog

All jobs involve some degree of training, but astronauts have to complete not only extensive physical and mental training, but also exercises to make them competent and confident about working in environments that are completely foreign to humans. For the Apollo 11 moon mission, for instance, astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin practiced landing on the lunar surface in the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle, which simulated the operations the two would have to complete in lunar gravity.

The National Archives has in its holdings a documentary by Todd Douglas Miller titled Apollo 11, which meticulously records the training that the astronauts completed before they rocketed into space.

TMSC (AV) – Astronaut Armstrong Training in the LLTV

(26 minutes 22 seconds)

No sound

National Archives Identifier: 81442926