Twice as Nice

Find us on Twitter

National Archives Foundation

@archivesfdn

For a year and a half, we at the Foundation have enjoyed bringing you our newsletter, American Experience with History Snacks. Each week, the staff considers an array of documents and themes to share from the Archives. The planning and decisions are less like an NFL draft board and more like finding the right ingredients while you cook.

With the fall season at the doorstep, we’ve been reflecting on what has already transpired in 2021 and decided to make this week a redux edition by serving up a few of our favorite stories from the past nine months. Let us know if you agree – share your favorite stories and documents with us on Twitter or Instagram. Or, tell us what themes and topics you’d like to see this Fall. Decisions, decisions!

Find us on Instagram

National Archives Foundation

archivesfdn

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

P.S. For our bowlers, don’t miss President Nixon’s form in the White House bowling alley at the bottom of this email!

We Shall Meet Again

Letter from John Boston to His Wife Elizabeth

National Archives Identifier: 783102

When the Civil War started, there were some 3.9 million slaves in the United States. While the nation was at war, many slaves in Southern states fled to the Union Army, risking everything for their freedom. One such man, John Boston, found refuge with a New York regiment in Upton Hill, Virginia. His 1862 letter to his wife who remained in Owensville, Maryland reveals the price many paid for their freedom. In his love letter to his wife, he wrote that his highest hope and aspiration was to be reunited with his family.

There is no evidence that Elizabeth Boston ever received this letter. It was intercepted and eventually forwarded to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

The Making of a City

Washington, DC, 1793-1859: L’Enfant Plan

National Archives Identifier: 57359241

When it came time to design Washington, D.C., President George Washington appointed Pierre Charles L’Enfant, a French engineer and architect who had fought in the U.S. Revolutionary War, to survey the swampy land that had been chosen for the capital city.

Editorial Note: Fixing the Seat of Government

Source: NARA’s Founders Online

The process of planning the city was complicated by disagreements about L’Enfant’s mandate and conflicts with other individuals, including Thomas Jefferson, then the Secretary of State. In the end, however, L’Enfant submitted a substantially more ambitious set of drawings that delineated the streets, canals, and bridges and many of the federal buildings. His plan was not fully realized, but portions of it are still evident in the city’s final form.

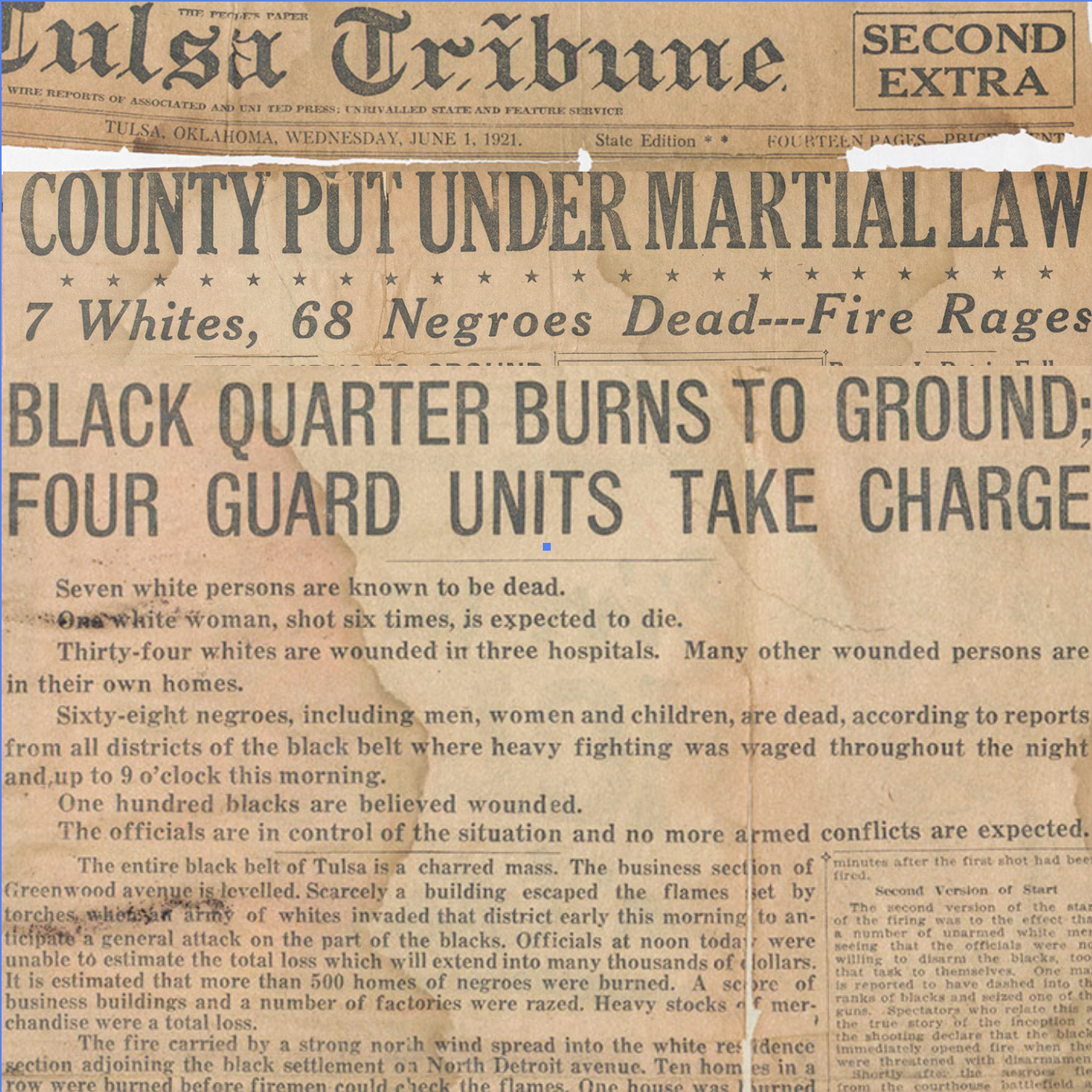

Black Wall Street: The Forgotten Tragedy

Newsclipping from the

Tulsa Tribune

June 1, 1921

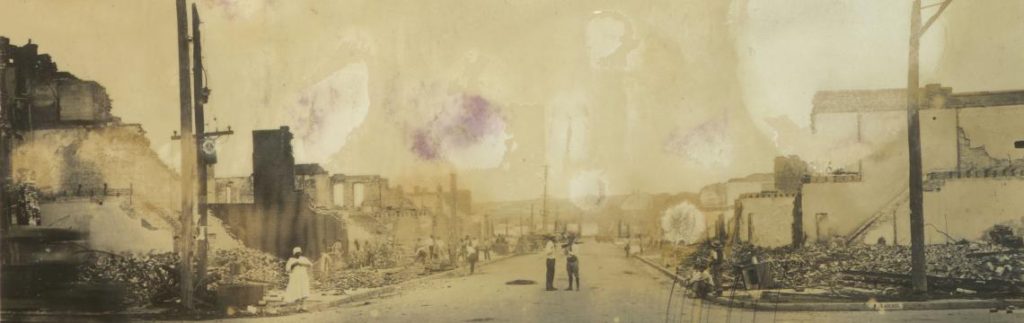

The Tulsa Race Massacre took place from May 31 to June 1, 1921, exactly one hundred years ago. Over that 24-hour period, white mobs attacked Black people and destroyed Black-owned businesses and property in the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma. The massacre was sparked by a report that a Black man, Dick Rowland, had assaulted a white elevator operator, Sarah Page, who later denied the claim.

The Greenwood district was well known as Black Wall Street, a business district that was home to the wealthiest Black community in the U.S. at the time. When the American Red Cross arrived in Tulsa the next day, they found that the area had been completely destroyed and 10,000 people needed their help. Rebuilding the district took more than 10 years.

Although it was widely and nationally reported at the time, the Tulsa Race Massacre faded from public awareness almost immediately. It was not until decades later that investigations were launched into the riots.

Read more about

Black Wall Street: 100 Years Since the Tulsa Race Massacre

The National Archives has played an ongoing role in keeping this story before the public. On Wednesday, May 26, the Archives Foundation hosted an online conversation titled “Black Wall Street: The Hidden Economy” that featured A’Lelia Bundles, a historian, author and journalist, Ron Busby, President and CEO of the U.S. Black Chambers, Inc., and Tristan Wilkerson, Managing Principal of Think Rubix, LLC and General Partner of High Street Equity Partners.

The participants’ observations were profound and sobering. “Between 1870 and World War I, there were more than 100 towns in the West founded by African Americans. The Greenwood section of Tulsa was one of those towns. . . . ,” Bundles said. “[W]hen [my great-great-grandmother] Madam [C. J.] Walker arrived in Greenwood, she would’ve seen a thriving community. In the 100 block of Greenwood Avenue, there were more than 70 businesses: four hotels, two newspapers, eight doctors, a movie theater, seven barbers, a cigar store, nine restaurants, and a half-dozen professional offices. But as we all know, that neighborhood was destroyed in a horrendous massacre on June 1, 1921.”

The event ended noting that even until this day, Black Tulsans have never been repaid for the loss of life, property and trauma that they endured over those two days. Though many in the community were resilient and went on to rebuild their businesses, many others left Greenwood, with their sources of both immediate and generational wealth gone.

If you missed the conversation or if you’d like to see it again, you can find it here.

(1 hours 7 minutes)

Source: National Archives Foundation YouTube Channel

History Snacks

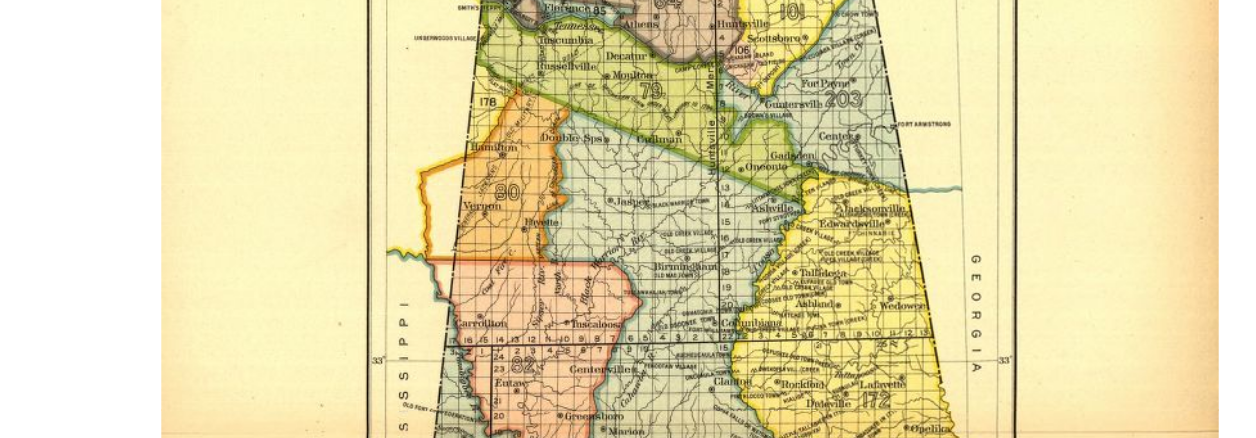

You Are Here

Alabama map

From the nation’s beginnings, the U.S. government made and then violated numerous treaties with Indian tribes, which often resulted in relocating entire native nations. Did you know which tribes once lived in what became your own backyard?

The Indigenous Digital Archive is your gateway to millions of Archives documents about Native Americans. You might want to investigate the IDA Treaties Explorer. Using the “Places” tab, you can search by city and state or zip code to learn which tribes lived in a specific place.

IDA Treaties Explorer

You can also use the “Cessations” tab to find out where tribes lived and where they were relocated to. Check out this map of Alabama and then click on the links below it to see additional maps of present-day Indian country.

Goggles…For Your Chickens?

The holdings of the U.S. Patent Office include millions of applications and approved patents for inventions of all descriptions. Some went on to be commercial successes, but others…not so much.

A case in point:

Eye Protector for Chickens

National Archives Identifier: 7460045

Patent #730,918 for—wait for it!—eye protectors for chickens. That’s right, chicken goggles! “This invention relates to . . . eye protectors designed for fowls, so that they may be protected from other fowls that attempt to peck them,” inventor Andrew Jackson, Jr., wrote, adding, “An additional object of the invention is to provide a construction which may be adjusted so that it will fit different-sized fowl.” Maybe chicken goggles are one of those inventions that you aren’t familiar with, but once you see them, you have to have them! The U.S. Patent Office records are housed in the National Archives, and chicken goggles are only the tip of the iceberg.