Thursday, April 1, 2021 – Thursday, June 17, 2021

Online

“— were dead. Figures are omitted [because] NO ONE KNOWS.” —Red Cross Report

On Memorial Day 1921, a Black shoe shiner named Dick Rowland rode in an elevator with white operator Sarah Page. The next day, Rowland was detained inside the Tulsa, Oklahoma, courthouse for the alleged assault of Page. Meanwhile, Tulsans gathered outside the courthouse to either witness or prevent Rowland’s possible lynching. During this gathering, shots rang out. For the next 24 hours, white mobs invaded the Greenwood District—a thriving and vibrant Black business and residential neighborhood in Tulsa also known as Black Wall Street. The mobs bombed, looted, set fire to buildings, and shot at random while Black residents defended their homes and businesses. Hundreds fled, and unknown numbers were killed.

The American Red Cross immediately responded, arriving the next day to find 35 city blocks completely destroyed and 10,000 people in need of relief. The Tulsa Race Massacre was the first time the Red Cross mobilized to provide relief outside of a natural disaster. From June through December, the Red Cross provided food, shelter, and medical care that would enable Black Tulsans to slowly rebuild the district over the next 10 years.

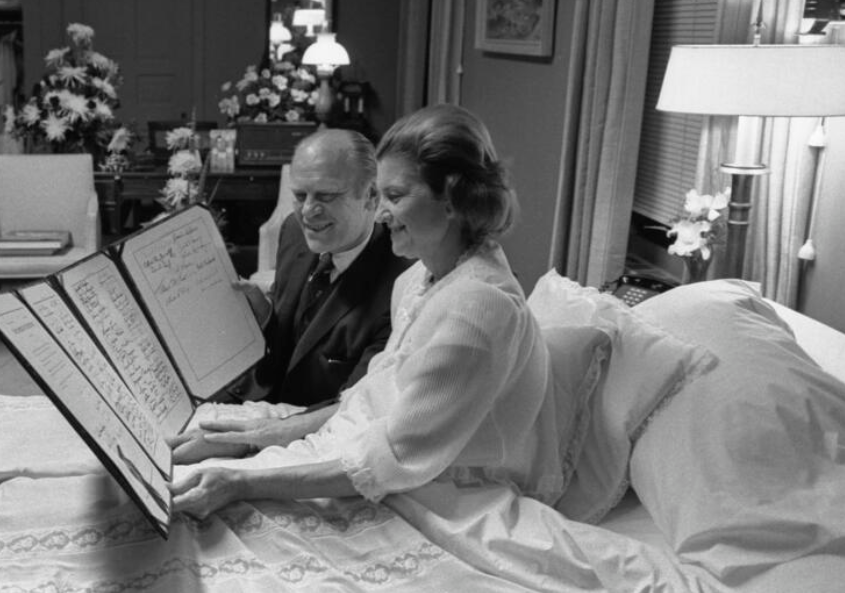

Photograph of Man Being Detained During the Massacre, May 31, 1921

National Archives, Records of the American National Red Cross, 1881-2008

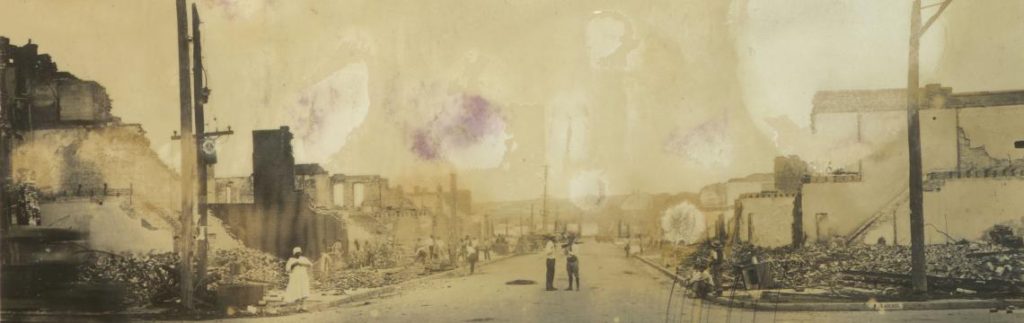

Ruins of the Titus Building, resettled by Mrs. Titus

National Archives, Records of the American National Red Cross, 1881–2008

The massacre was widely reported at the time, and records like those displayed here document many facets of the story. Yet, for decades the massacre was rarely mentioned publicly in Tulsa and was omitted from most mainstream American history texts and curricula. Today, active investigations into possible mass graves, inclusion in educational curricula, dramatic depictions in television and film, and other reconciliation efforts are being made to attempt to bring awareness, healing, and closure.

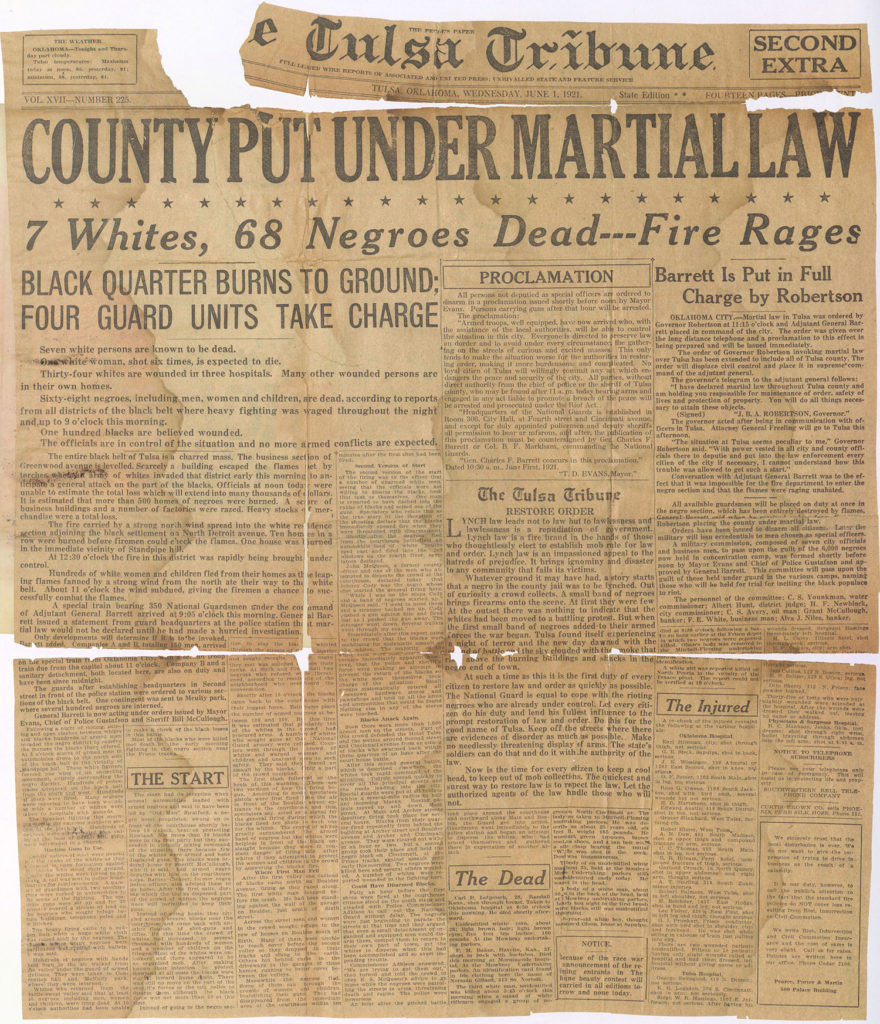

National Archives, Records of the American National Red Cross, 1881–2008

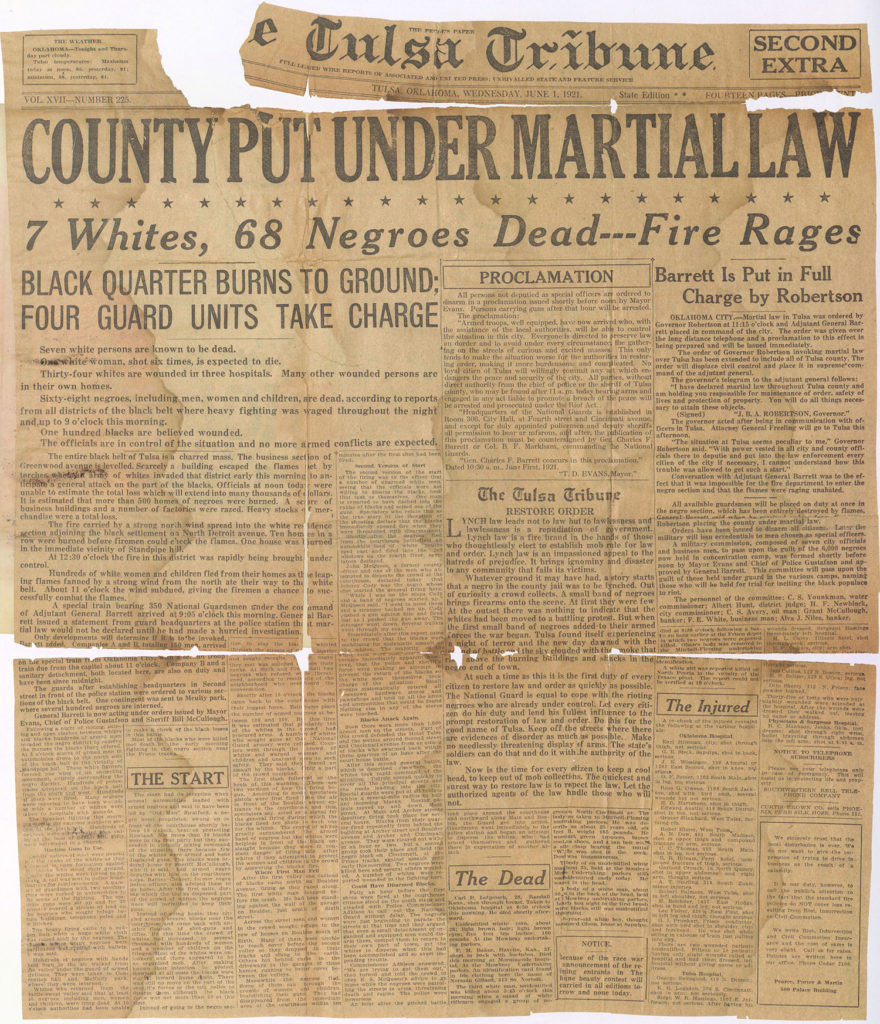

The Tulsa Tribune was one of the local newspapers that reported the events of May 31 and June 1, 1921. This issue describes a scene from the massacre: “The machine guns were set up and for 20 minutes poured a stream of lead on the negroes who sought refuge behind buildings, telephone poles, and in ditches.” The Tribune’s article from May 31, “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in an Elevator,” may possibly have fueled the anger of the white mob. Charges were eventually dismissed in this case when the alleged victim refused to give a statement.

This was not the first or only attack on an African American community in the United States during the Jim Crow era. Jim Crow codes relegated Blacks to second-class citizenship, and any real or perceived violation (including Black success) could be cause for violence.

Banner Image: Photograph of People Standing Amid Rubble in the Greenwood District, June 1, 1921. National Archives, Records of the American National Red Cross, 1881–2008

The 100th Anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre Featured Document Display is made possible in part by the National Archives Foundation through the generous support of The Boeing Company.