Archives Experience Newsletter - September 14, 2021

…to form a more perfect union…

Most of the nearly 1.5 million visitors who pass through the Rotunda of the National Archives to see the Constitution, which spells out the founding architecture of our government and nation, don’t fully realize that the ‘ye old parchment paper’ they are peering at is a living document.

While the Founders knew the document was imperfect and full of compromises, they realized that it would need to be amended after it was signed, and also over the course of our nation’s lifetime. Hence, Article V, and soon thereafter the Bill of Rights.

The Constitution and its 27 Amendments are rich with stories and drama from how they came into being to their ongoing interpretation. Some amendments have all the fun. The first and second see their fair share of debate, and the fifth makes an appearance in almost every courtroom drama on TV. But what about the amendments that don’t get as much attention?

In the spirit of our mission to bring forward the untold stories found in the Archives, we’re celebrating Constitution Day (this Friday!) by highlighting the amendments that are less familiar. What relationship might the third amendment have to your apartment lease, or how did tax season get so complicated? We’ve got the answers.

Happy Constitution Week!

<

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

The Third Amendment

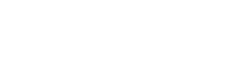

We haven’t heard much about the Third Amendment to the Constitution in the past 230 years, but the issue it addresses was a hot-button item in the American Revolutionary period. King George III of England had regularly installed his soldiers in private homes at the expense of those who lived there. The issue was so

heated that in the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson specifically admonished the king “for quartering large bodies of armed troops among us.”

Intolerable Acts (from Pennsylvania Journal)

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

Consequently, the Third Amendment was incorporated into the Bill of Rights. It reads, “No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.”

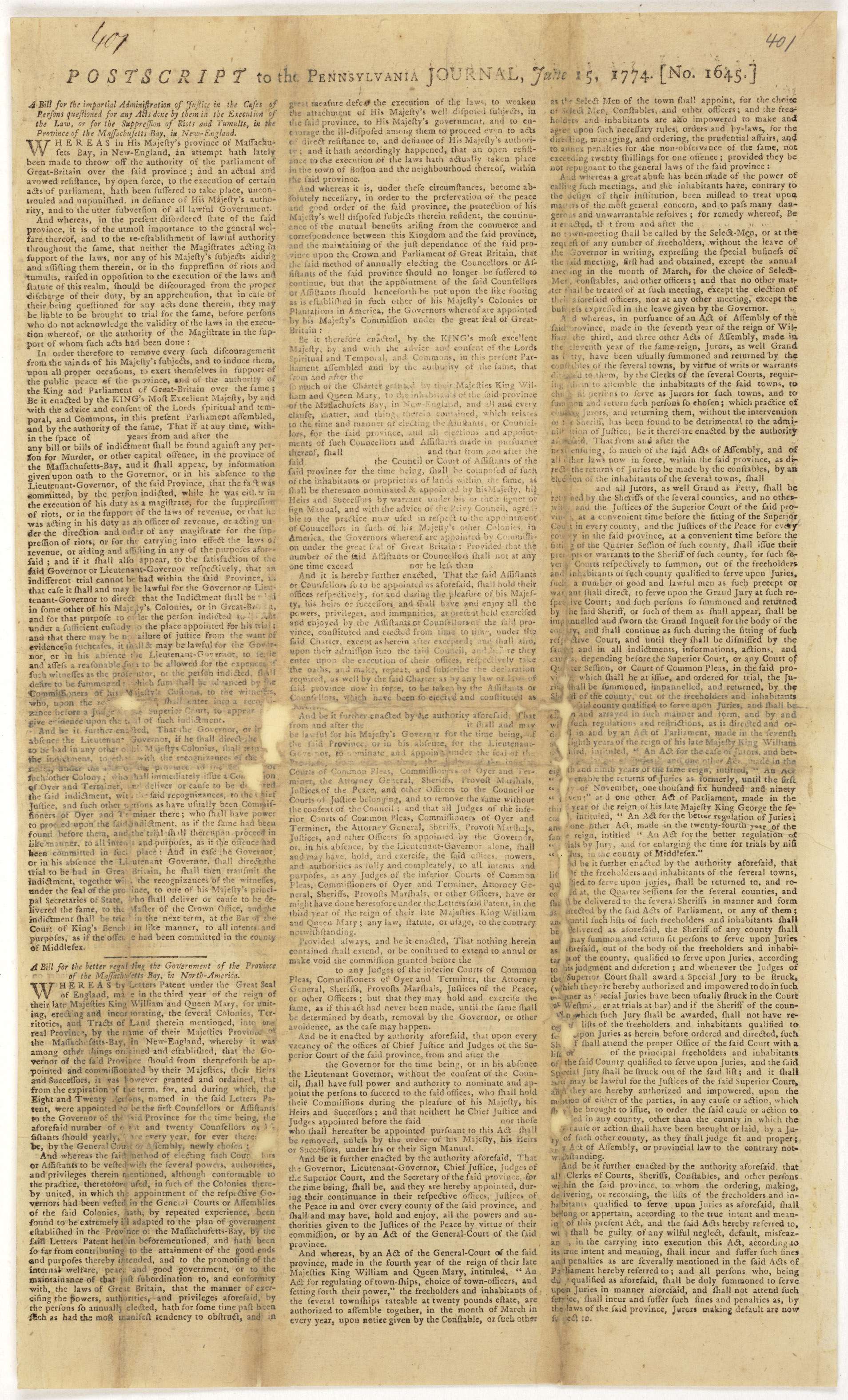

Continental Congress’ Declaration of Rights and Grievances against Great Britain

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

Until this year, the Third Amendment had not been subjected to the scrutiny of the Supreme Court, but the Third Amendment Lawyers Association has recently filed an amicus brief that supports overturning the CDC’s recent moratorium on evictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. The brief states, “The CDC moratorium on evictions has the tendency to invade the Third Amendment rights of landlords.” It argues that some of those who would otherwise be evicted are soldiers, and thus, their landlords are being forced to “quarter” soldiers in their properties at their own expense.

On August 26, 2021, the Supreme Court overturned the CDC’s ban on evictions, but the decision did not discuss this novel interpretation of the Third Amendment.

Why else might this seldom-discussed amendment be relevant today? Many Constitutional scholars have pointed out that it’s the only amendment that talks about the relationship between civilians and the military during both war and peacetime. It also has powerful implications for a core belief of the Founding Fathers: that civilians should have control over the military. So while the Third Amendment rarely sees air-time in the news, that doesn’t mean the protections it ensures aren’t essential.

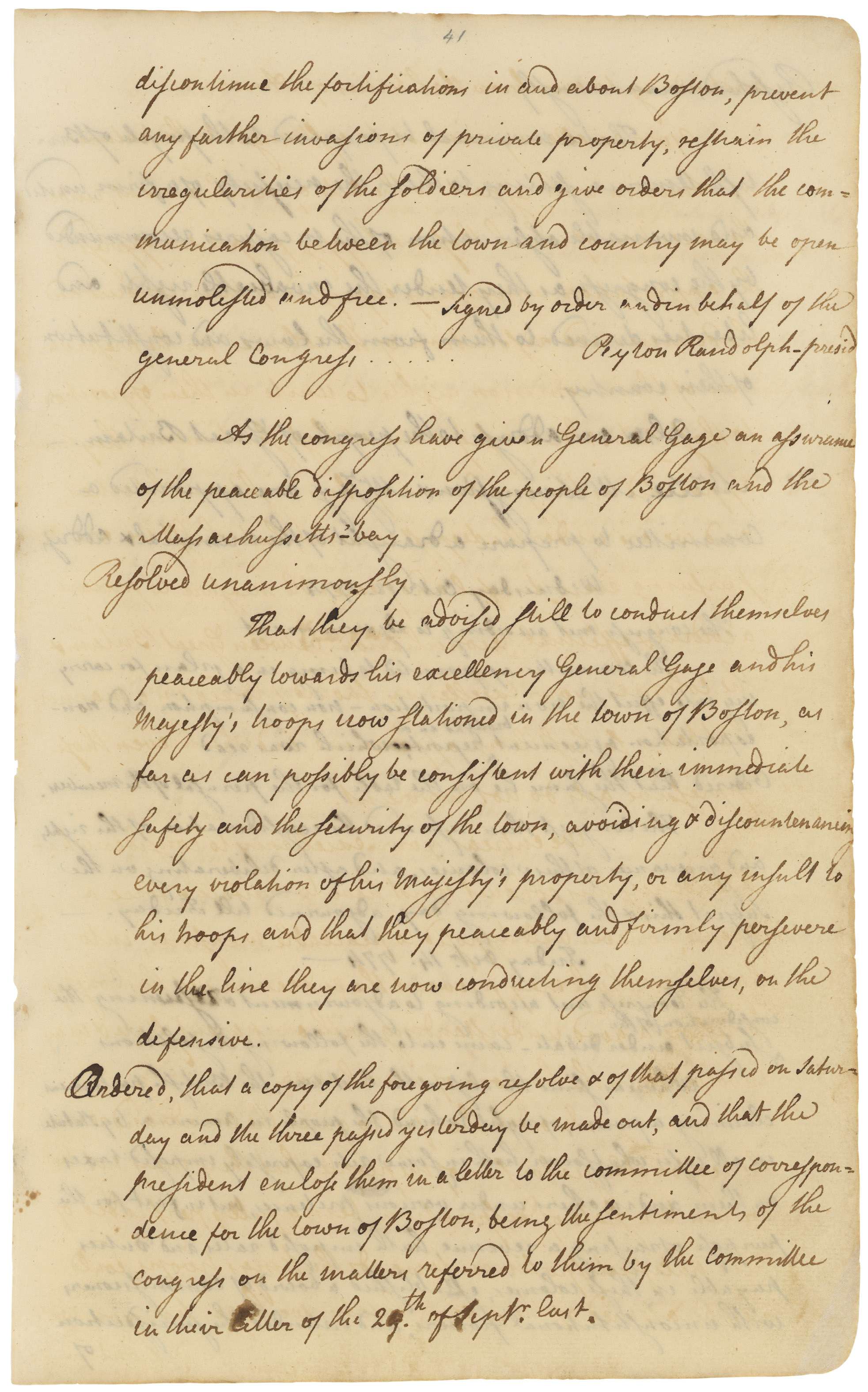

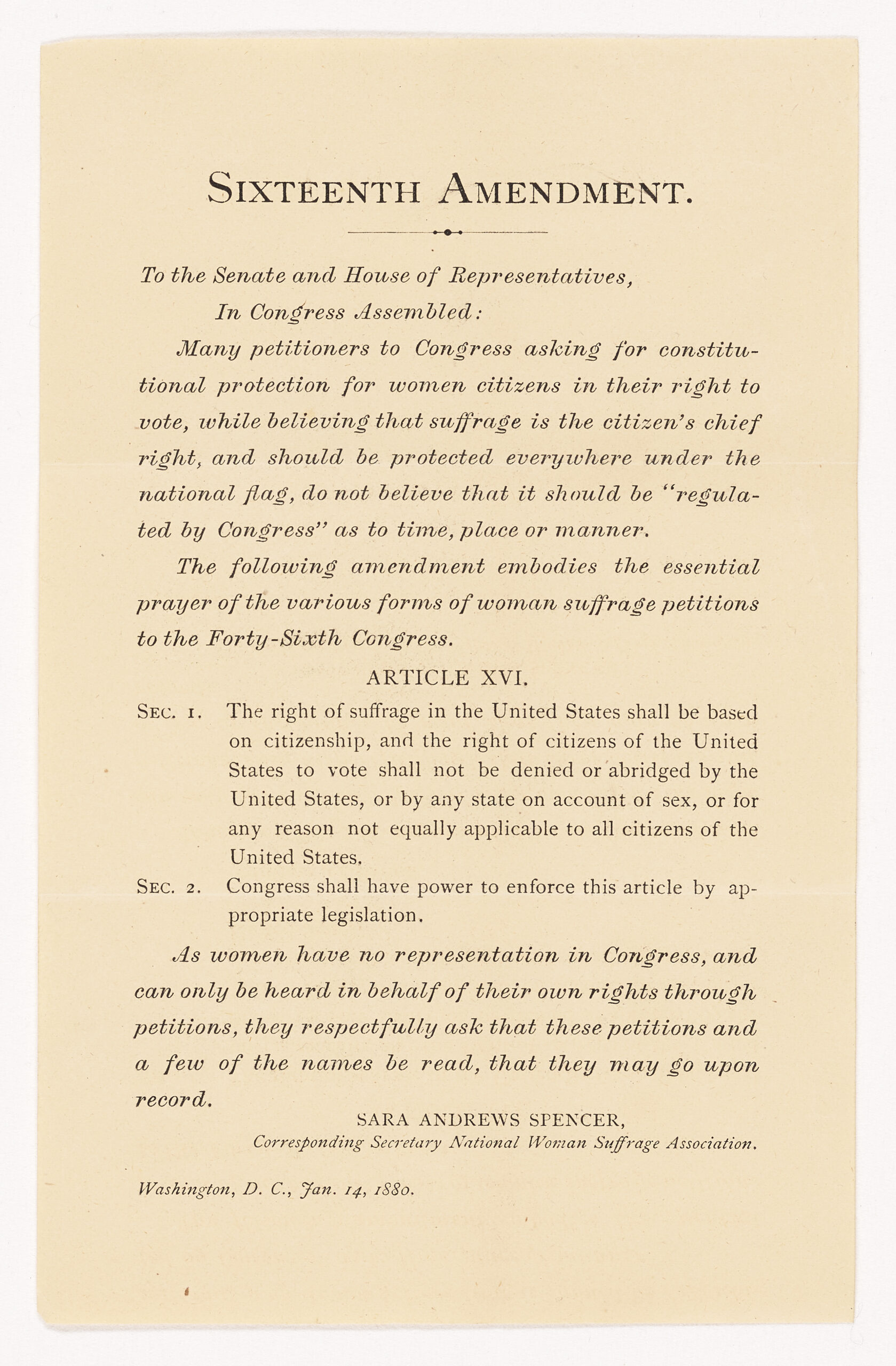

The Sixteenth Amendment

Calculating New Income Tax

National Archives Identifier: 6011549

Oh, how we hate tax season in the United States! This attitude probably arises from the colonists’ conflicts with the British government over “taxation without representation,” which became a rallying cry of the American Revolution.

The struggle to mandate a federal income tax has been long and bitter. Abraham Lincoln first proposed an income tax in 1861 to raise money to pay for the impending war. The Revenue Act of 1861 included the nation’s first personal income tax, a charge of 3 percent on those making more than $800 per year. In 1872, Congress repealed the income tax, but the Sixteenth Amendment reinstated the tax in 1913.

National Archives Identifier: 119222110

How did this come to be? In a joint address to Congress in 1909, President William Howard Taft introduced the idea of a two percent federal income tax on corporations, and a Constitutional amendment to reinstate the previously-enacted income tax under Lincoln. Previously, the main source of revenue to the U.S. government was tariffs, but at the turn of the century, an increasingly industrialized world prompted concerns about the revenue needing to maintain a strong central government and standing military in the face of the sophisticated military forces of Russia, Japan, and Britain.

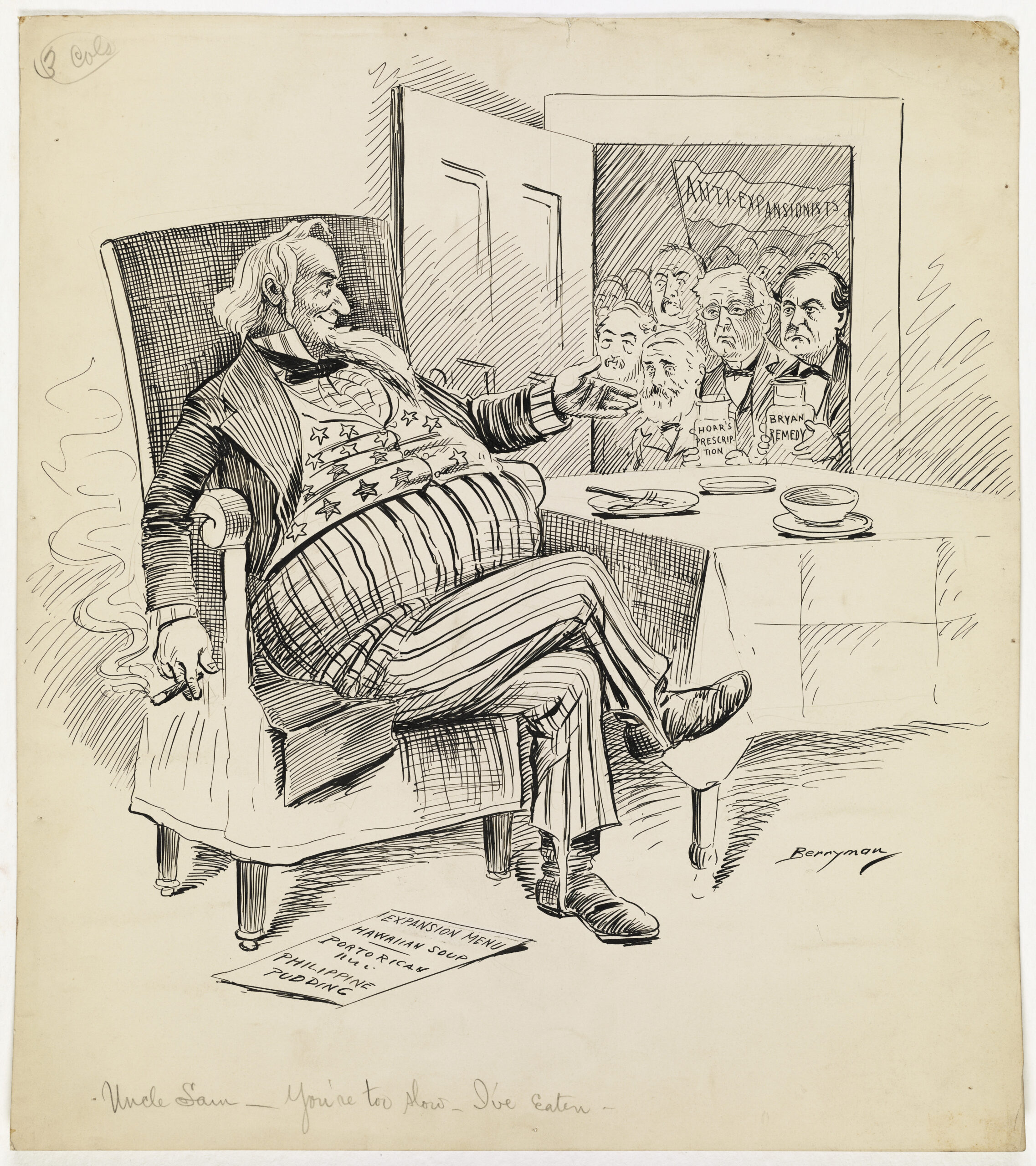

Uncle Sam-“Too late, my boys. I’ve already expanded.”

National Archives Identifier: 6010331

Increased revenue was needed not only to defend American merchant interests, but also to further carry out their imperialist ambitions, which began in the late 1800s.

The Twenty-Seventh Amendment

The Bill of Rights: A Transcription

NARA’s America’s Founding Documents

When the Continental Congress originally drafted the amendments that became the Bill of Rights, they numbered twelve. The states ratified ten of those amendments and declined to ratify the other two. Article One addressed how the number of members of the House of Representatives would be determined. In 1928, Congress finally settled the issue when it passed the Permanent Apportionment Act.

A Record-Setting Amendment

NARA’s Pieces of History blog

Opinion on Apportionment Bill

Source: NARA’s Founders Online

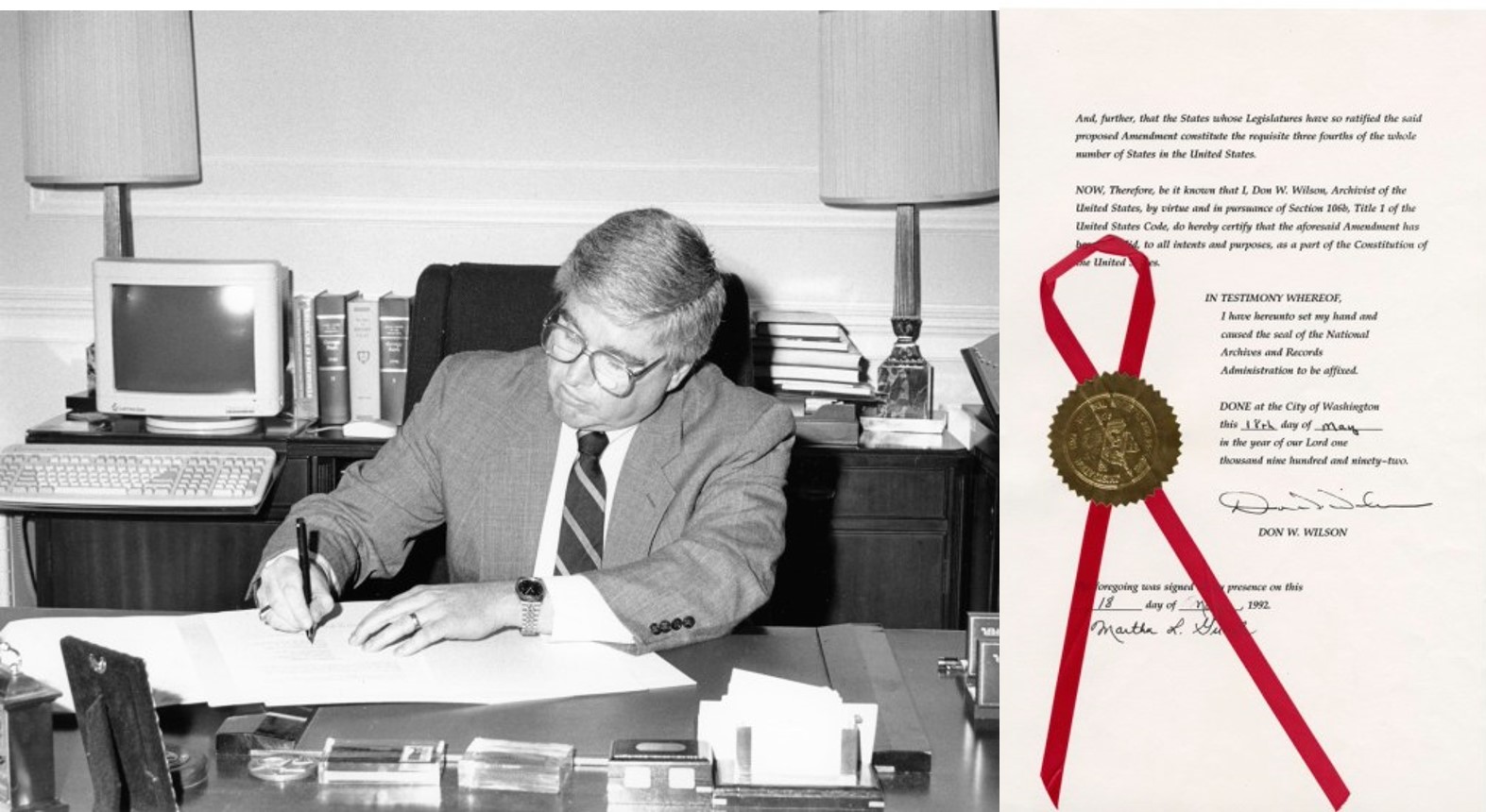

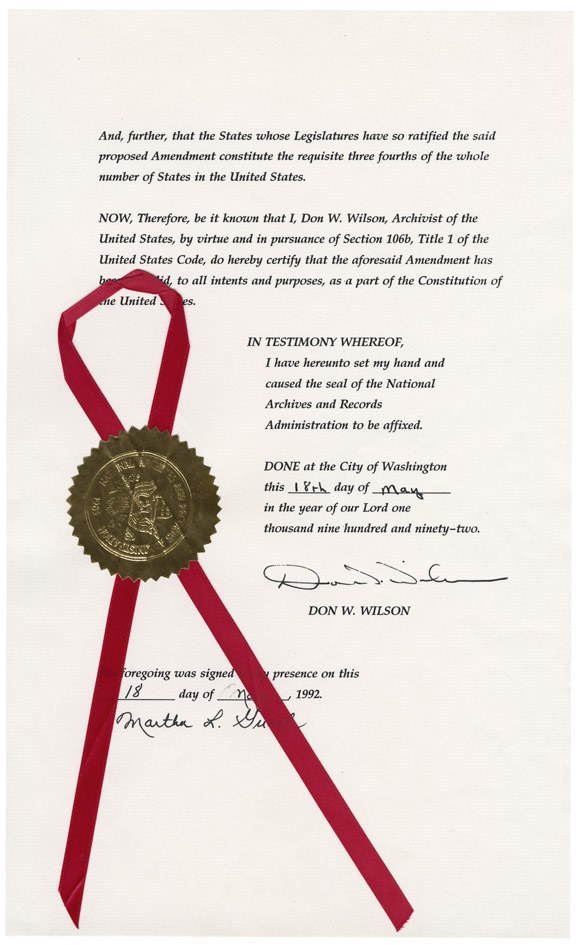

Article Two addressed the compensation for members of Congress, stating that members could not give themselves a pay raise that would take effect during that same session. The amendment languished unratified until Gregory Watson, a student at the University of Texas at Austin, wrote a paper arguing that because the proposal was never taken “off the table” , that it was still active and should be considered. He began to campaign for its ratification, and though it took another eleven years, the Twenty-Seventh Amendment was finally ratified on May 18, 1992, 203 years after it was proposed. It reads, “No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of Representatives shall have intervened.”

Certification of the 27th Amendment

National Archives Identifier: 1512313<

After the amendment’s passage, it was certified by Archivist Don W. Wilson – the first and only Archivist to certify a Constitutional amendment – during a small ceremony. If you’re curious about the role of the Archives in the Constitutional amendment process, you can read more about it here.

The National Archives’ Role in Amending the Constitution

Source: NARA’s Prologue Magazine

History Snacks

Spelling Bee

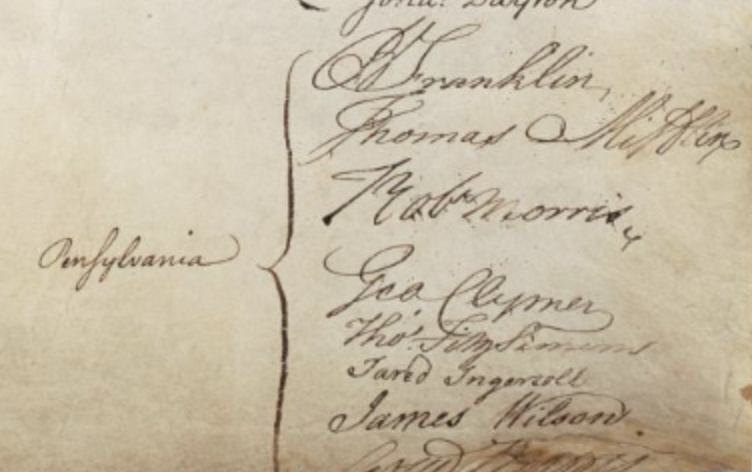

Here’s proof positive that even the Founding Fathers sometimes made mistakes: there’s a BIG misspelling in the U.S. Constitution. Did you guess it? It’s Pennsylvania, but they left out one “N”, spelling it instead “Pensylvania”, as you see here. Whoops!

Race to Ratify…or Not

When it came to the ratification of the Constitution, the framers were nervous that individual states might not be receptive to this new form of government.

For some states, their fears were unfounded. Vermont ratified the Constitution before it ever became a state on January 10th, 1791 (they would not become a state until later that year on March 4th).

An Act from the State of New York Ratifying Certain Articles in Addition to and in Amendment of the Constitution

National Archives Identifier: 1685236

For other states, their fears were confirmed. Rhode Island, which did not send any delegates to the Constitutional Convention, was the last holdout. The smallest state sure put up the biggest fight, having a popular vote in 1788 on whether to ratify – voting 237 in favor and over 2,000 opposed. Rhode Island did not ratify the document until 1790. George Washington had been President for over a year, and they had to write him directly to accept the Constitution.

From the Rhode Island Ratifying Convention

Source: NARA’s Founders Online

Other states were in somewhat of a middle-ground. New York was the 11th state to ratify the document, but not without proposing changes. Their ratification document was the longest, accepting certain articles and adding amendments.