Archives Experience Newsletter - July 4, 2023

Revolutionary

In our May 23 issue of the Archives Experience, “America on Stage,” we purposely left out one of the most important Broadway musicals of the past century. Written by Sherman Edwards and Edward Stone, 1776 ran for 1,217 performances, was adapted into a film, and has been revived on Broadway in 1997 and again in 2022.

1776 was revolutionary. It depicted the Founding Fathers as the people they were, not the demigods created by the passage of time and proliferation of folklore. And it inspired later depictions of the Founding Fathers, most recently Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton.

Obviously, 1776 rewrites some history to keep the show entertaining, but the storyline sticks pretty close to historical fact. But just to be sure, let’s check the Broadway book against the National Archives holdings…

In this issue

Virginia was considered an aristocracy and the Lees stood at the head of that line…

The Lees of Old Virginia

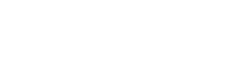

Lee Resolution for Independence, June 7, 1776

Richard Henry Lee was born in Westmoreland County, Virginia, in 1732, into a prominent family of politicians, military leaders, and diplomats that eventually included Robert Edward Lee, the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia of the Confederacy. As the first British colony in the Americas, Virginia was considered an aristocracy, and its inhabitants aristocrats, and the Lees stood at the head of that line. Richard Henry Lee’s father, Colonel Thomas Lee, served as governor of Virginia. Both of Lee’s parents died in 1750 while Lee was studying in England, and he returned to Virginia in 1753 to settle his parents’ estate.

In 1757, Richard Henry Lee began his political ascent when he was appointed justice of Westmoreland County. In 1758, he was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses, where he became an early advocate for independence from Britain.

Votes on the Lee Resolution

Lee was chosen as a delegate to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia in August 1774. Then during the Second Continental Congress, on June 7, 1776, Lee introduced what became known as the Lee Resolution, which stated:

Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances.

That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation.

It is absolutely true that John Adams, a delegate from Massachusetts, had tried repeatedly to get Congress to consider declaring the colonies independent of England, but the other delegates pointedly refused to take up the issue. When Lee proposed it, however, they felt they had no choice but to take it under advisement.

But, Mr. Adams!

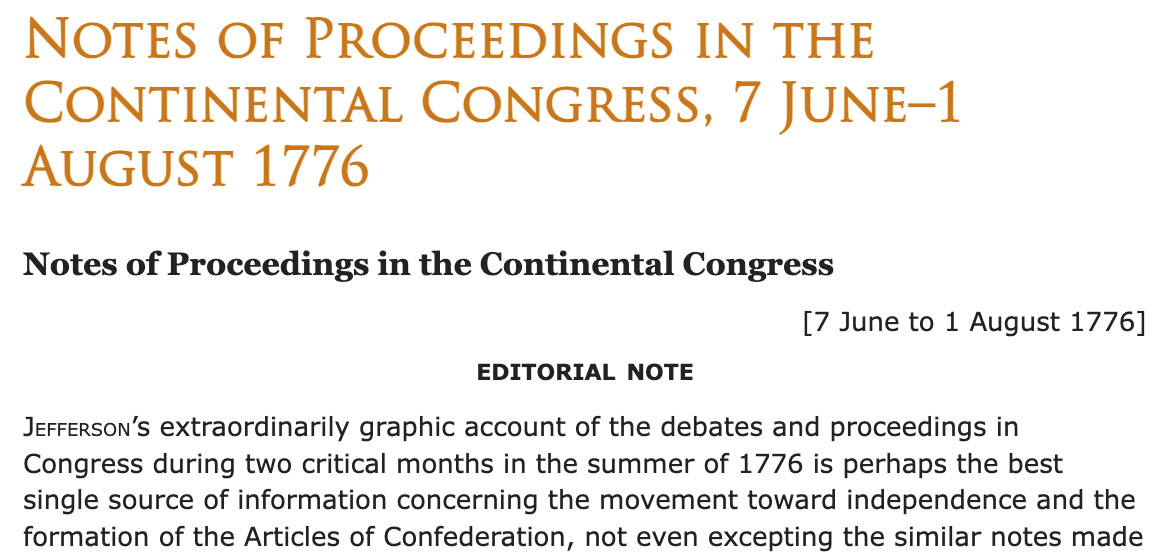

After Richard Henry Lee introduced his resolution to Congress, the delegates postponed voting on for three weeks while they recessed. In the meantime, the Committee of Five, comprised of Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Robert Sherman, Robert Livingston, and Thomas Jefferson, were commissioned to write a statement laying out for the world the colonies’ argument for their independence from Britain.

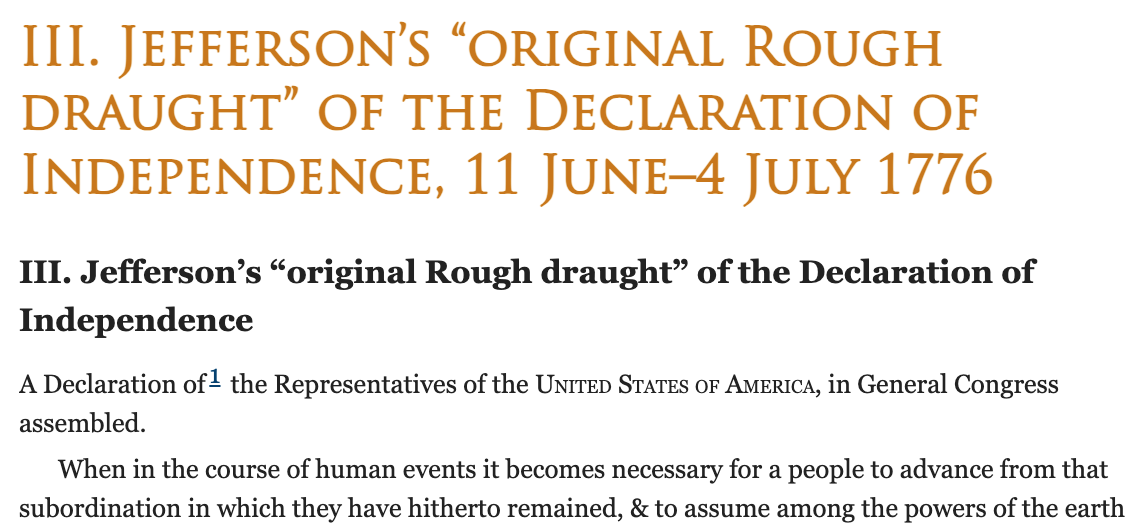

Four of the five members insisted that Jefferson was the man for the job: they “unanimously pressed on myself alone to undertake the draught [sic],” Jefferson later wrote. “I consented; I drew it; but before I reported it to the committee I communicated it separately to Dr. Franklin and Mr. Adams requesting their corrections. . . I then wrote a fair copy, reported it to the committee, and from them, unaltered to the Congress.” Jefferson adopted some of the wording of Lee’s resolution into the Declaration of Independence.

Notes of proceedings of the Continental Congress June 7 – August 1, 1776

Source: NARA’s Founders Online

John Adams’ recollection of how he urged Jefferson to draft the declaration was rather blunter: “Reason first—You are a Virginian, and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business. Reason second—I am obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular. You are very much otherwise.”

When the Congress met again on July 1, the committee presented the draft declaration, and then the real horse-trading began. The delegates agreed that all the colonies had to unanimously consent to the declaration, so they debated about the wording for three full days, picking at it, changing a word, cutting entire phrases and paragraphs. Thomas Jefferson preserved the first draft in his personal papers, so we can compare the original version to the final document that the delegates signed.

Till Then

Jefferson’s original draft

Source: NARA’s Founders Online

Of course, the biggest sticking point about the declaration was whether slavery would be discussed in it. In Jefferson’s first draft, he condemned King George III of England for being one of the principal instigators of the transatlantic slave trade, which Jefferson viewed as a crime against humanity—quite an irony, considering that he himself was a slaveholder.

The delegates from Georgia and South Carolina both objected adamantly to this clause, and delegates from several Northern colonies sided with them because although slavery was either illegal in their colonies or was very uncommon, they nevertheless profited from doing business with colonists who were slaveholders. To persuade them to vote for the declaration, Jefferson agreed to strike the offending clause from the final version of the document.

Transcription of the Declaration as adopted by Congress

Source: NARA’s Founders Online

In 1776, when it becomes clear that slavery will not be mentioned in the declaration, John Adams says, “Mark me, Franklin, if we give in on this issue, posterity will never forgive us.” In fact, it was John’s cousin Samuel Adams, who was also a delegate to Congress, who made this prediction, but what he actually said was, “If we give in on this issue, there will be trouble a hundred years hence; posterity will never forgive us.” And sure enough, in just short of 100 years, the issue of slavery ripped the nation apart.

In their “Historical Note” at the end of the published version of 1776, Stone and Edwards explain that they altered the statement because “audiences would never forgive us. For who could blame them for believing that the phrase was the author’s invention, stemming from the eternal wisdom of hindsight?”

Cool, Cool, Considerate Men

John Dickinson Continental Army service record

National Archives Identifier: 31042356

Dickinson’s Olive Branch petition via Library of Congress

John Dickinson was one of three delegates from Pennsylvania, the other two being Benjamin Franklin and James Wilson. Dickinson was outspoken in his belief that the colonies should not declare their independence at that time and should instead continue trying to reconcile with Great Britain. Dickinson had written the Olive Branch Petition, the Second Continental Congress’ last effort to make peace with England, which it submitted on July 5, 1775, but King George III did not even read it. Neither did he read the subsequent petition submitted three days later on July 8 (but you can, via Founders Online).

July 8th Olive Branch petition

Source: NARA’s Founders Online

Dickinson was a member of the committee that Congress had appointed to write the Articles of Confederation, and he had largely written the first draft. When Congress started debating the Declaration, Dickinson kept insisting that instead of opting for independence, the colonies should complete the Articles of Confederation and make alliances with foreign countries such as France first.

When the time came to vote on the Declaration, Dickinson abstained, and he also refused to sign it. Instead, he left Congress and joined the Pennsylvania militia. John Adams, who regularly and loudly debated John Dickinson on the floor of Congress, said of him, “Mr. Dickinson’s alacrity and spirit certainly become his character and sets a fine example.” Dickinson joined the Pennsylvania militia as a private, refusing to accept an officer’s commission.