Archives Experience Newsletter - October 26, 2021

Red-handed Records

Happy Halloween! This is the time of year when we gather around campfires or movie screens to hear a ghost story or watch a horror film. This isn’t a newsletter about how the Archives Building in Washington, D.C., is haunted – although some guards on the night shift may debate that. This Halloween issue will give you a few spooky chills as we delve into the true crime records housed in the Archives.

The subject of true crime has exploded in popularity. Podcasts and shows dissect the minutiae of criminal cases. And what’s the “smoking gun” ? That’s right: documents. Look at the evidence yourself, from some of the most notorious arrest records to the dark secrets behind a wellness cult gone bad. There’s nothing scarier than the truth!

Boo Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

(Crime) Family Affairs

Al Capone and Whitey Bulger had one thing in common: these two infamous American gangsters successfully avoided going to prison for many years. Al Capone ruled the Chicago Outfit, an organized crime syndicate, throughout Prohibition. He ran the bootlegging operations there and is reputed to have ordered many murders, including the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre of seven associates of a rival gang. No matter how blatant his actions, however, the authorities could not find enough direct evidence to charge him for his crimes. Capone finally met his match after U.S. Assistant Attorney General Mabel Walker Willebrandt successfully argued before the Supreme Court in 1927 that illegal income should be taxed. Like many other mob bosses, Capone hadn’t been paying federal income taxes on his ill-gotten gains. Despite his efforts to get a plea bargain and then to bribe members of the jury, on October 18, 1931, Capone was convicted of tax evasion and sentenced to eleven years in prison.

criminal case file

of Al Capone’s tax evasion case

this list maintained by the San Francisco Archives

Whitey Bulger was a gangster and mob boss from Massachusetts who became an informant for the F.B.I. so the agency would not look too closely into the actions of the Winter Hill Gang, the organized group he led. Starting in 1975, Bulger fed the agency information about his rivals, the Patriarca crime family.

In 1994, tipped off by his FBI handler, Bulger went into hiding. He remained at large for sixteen years. He was finally apprehended in Santa Monica, California, in 2011. He was tried and convicted of thirty-one counts of firearms and racketeering charges and was implicated in more than ten murders. He was transferred to the U.S. Penitentiary, Hazelton, in West Virginia, on October 30, 2018. The next morning, he was found beaten to death in his cell.

The National Archives holds records pertaining to Whitey Bulger since his early crime days in the 1950s, including his warrant for arrest and indictment for fixing horse races.

False Accusations

Read

The Scottsboro Boys INJUSTICE IN ALABAMA

in Prologue Magazine

The case of the Scottsboro boys is one of the most notorious in the history of racial injustice in the United States. It became a seminal event in the Civil Rights Movement.

On March 25, 1931, near Chattanooga, Tennessee, nine young Black men aged thirteen to nineteen, who had hopped a freight train bound for Memphis, got into a fight with several White men on the train. Two White women were on the train as well. The fight ended when the Black men threw all but one of the White men off the train.

The men who had been tossed off the train went to the local sheriff and accused the Black men of assaulting them. The sheriff assembled a posse that rounded up the Black men, and then, the two White women accused six of the Black men of raping them. Even though medical evidence of rape was notably absent, eight of the young Black men were convicted of rape and sent to prison. The convictions sparked massive protests; 145,000 thousand people signed a petition asking President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to intercede on the boys’ behalf. Roosevelt did not respond to the petition.

The convictions were appealed all the way to the United States Supreme Court, which twice overturned them. In 1934, about three years after the young men’s convictions, their mothers appealed directly to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, asking him to free their sons.

Despite the mothers’ plea, Roosevelt again declined to get involved in the case.

The trials, retrials, and Supreme Court rulings kept the issue in the public eye for years. Eventually, several of the Scottsboro boys were pardoned. It goes without saying, however, that being unjustly convicted of heinous crimes and serving time for them often ruins the lives of the accused.

Attack on Antelope

According to the 1980 census, the town of Antelope, Oregon, located in the north central desert of that state, was home to thirty-nine people. A year later, in July 1981, the Bhagwan Shri Rajneesh and his spokesperson, Ma Anand Sheela, established a religious community, Rajneeshpuram, on the Big Muddy Ranch, a 64,229-acre property adjacent to Antelope. They initially stated that they planned to run the commune as a self-sustaining agricultural society, but it became clear very quickly that they had much bigger plans.

The Bhagwan’s followers, called Rajneeshees, started building a restaurant, a shopping mall, a hotel, and police and fire departments. Many of these projects were not properly permitted by the county. In very short order, more than 7,000 Rajneeshees were living on the ranch.

National Archives Identifier: 77848260

In April 1982, the Rajneeshees voted overwhelmingly to take over the town of Antelope. They renamed Antelope “Rajneesh,” reincorporated the Big Muddy Ranch as “Rancho Rajneesh,” and then set their sights on taking over the entire county. It looked like the members of the commune were succeeding in making the entire area part of Rajneeshpuram.

However, beginning in October 1981, legal setbacks began to befall the community. The U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service launched a full-scale investigation of the Bhagwan and the Rajneeshees and compiled a laundry list of their illegal activities. In what became known as “the only episode of domestic mass bioterrorism in America,” leaders of the commune set out to steal a county election by contaminating the water supply of The Dalles, the biggest town in the county, with salmonella and thus keep people away from the polls. They tested their plan by purposely giving county officials water laced with the bacteria and spreading it on produce in grocery stores and on the salad bars of ten restaurants. More than 700 people got sick, and 500-plus of the afflicted filed suit against the commune as a result. You can read an account starting on page 38 of this report.

National Archives Identifier: 44170334

In addition, the Bhagwan publicly stated that Sheela had stolen millions of dollars from the commune and that its residents were hiding a cache of assault weapons. The latter statement prompted multiple state and federal agencies to start investigating the commune.

By October 23, 1985, Sheela and several of her followers had fled the U.S. for Germany, where they were soon arrested. On October 28, the Bhagwan was arrested in Charlotte, North Carolina, where he was trying to escape from the U.S. on a private aircraft bound for Bermuda. He was taken back to Oregon to face a thirty-five–count indictment of immigration charges. His attorneys worked out a plea agreement that allowed him to plead guilty to two felony charges, pay the court costs, and leave the country. In November, the Bhagwan returned to India, where he died in January 1990.

In the absence of their leaders, the Rajneeshees started fleeing the commune by the busload. The residents of Antelope regained control of their town about a month later. Sheela was extradited to the United States, where she was tried and sentenced to up to twenty years in prison and ordered to pay a fine of $400,000 for directing the salmonella poisoning in The Dalles, running an electronic wiretapping system at Rancho Rajneesh, and plotting to murder the Bhagwan’s personal physician.

The story of Rancho Rajneesh is a cautionary tale about the dangers of blindly following a charismatic leader with corrupt and power-mad followers. The situation was so serious that President Clinton was briefed on the matter, and the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine issued a detailed report about the events there.

An Unsolved Archives Mystery

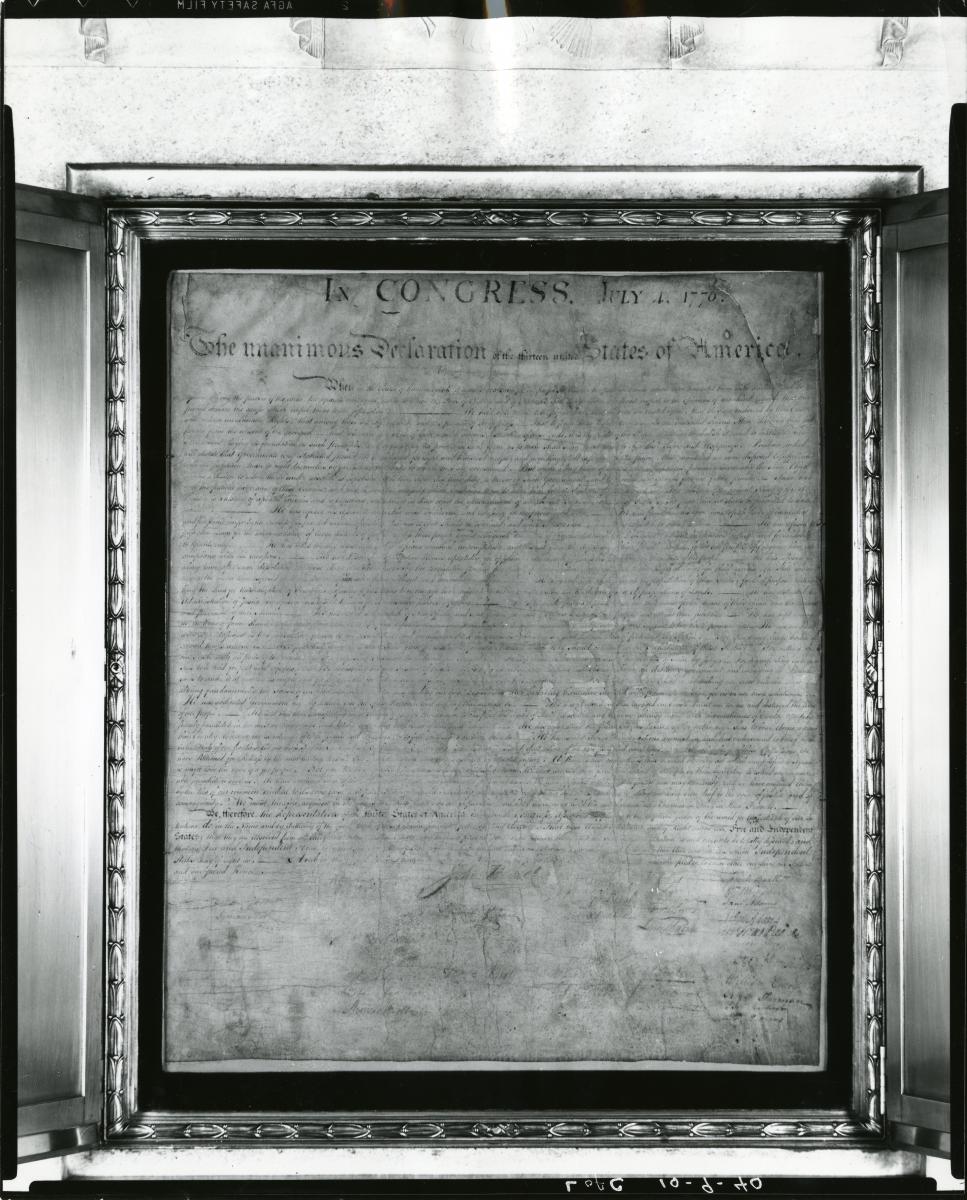

Two hundred and forty-five years ago, the Founding Fathers signed the Declaration of Independence, one of the United States’ three Charters of Freedom. Since that time, the document has been protected by several government agencies, starting with the Continental Congress, which took it from place to place during the Revolutionary War. Since then, the U.S. Department of State, the Library of Congress, and, finally, the National Archives have been charged with preserving and protecting the Declaration. More than 245 years of being moved and displayed have taken a toll on the document, but the agencies were extremely careful with it and handled it according to the best conservation practices of the time. The Declaration has undergone several rounds of treatments for light and insect damage. It is now displayed in the Rotunda of the National Archives building, enclosed in a titanium-aluminum–framed case filled with argon gas.

In November 1940, conservator George Stout of Fogg Museum at Harvard University discovered a baffling detail when he examined the Declaration at the Library of Congress—a faint imprint of a hand on the lower left of the document. How and when the handprint was made are not known, although it was not evident in a photograph of the document made in 1903 by L. C. Handy. Who could possibly have left this handprint?

Smile for the Camera

Mug Books: An Unusual Avenue of Genealogical Inquiry

Source: NARA’s Unwritten Record blog

Do you suspect that your great-great-uncle might have been a stickup man in the northeastern U.S. between 1883 and 1890? The National Archives might be able to help you learn more about that. Staff members at the Archives have digitized more than 700 cards from mug books in the holdings. Most document people who were arrested in Washington, D.C., although some of the mug books are from New York City, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. Each card features a photograph of the offender on the front and a physical description on the back, including details like height, weight, and mannerisms.