Archives Experience Newsletter - March 1, 2022

Parks and Recreation

From sunrises at Acadia National Park in Maine to sunsets at Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park, the natural beauty of our nation is undeniable. Spread out across the United States, the National Parks Service is made up of 423 sites that offer a plethora of experiences. Some may enjoy a less vigorous park adventure – like gazing at St. Louis and the Mississippi River from atop the Gateway Arch or touring monuments here in Washington, D.C. I enjoy all of them. Our citizens and tourists alike are lucky to have more than 84 million acres of publicly protected and accessible land to enjoy. But that legacy had to start somewhere.

On March 1, 1872, Congress designated the first federally protected land, Yellowstone National Park, in Wyoming and Montana. Although it was new to many Americans, the area had been inhabited by Indigenous peoples for at least the past 11,000 years. Now, the park is renowned for its Old Faithful Geyser, the iconic Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River, and more than 5,000 bison – something you will NOT see at our monuments here in D.C.!

This week, the Archives’ holdings are helping us celebrate the 150th anniversary of Yellowstone National Park. Join us for the expedition.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

“Road Trip”

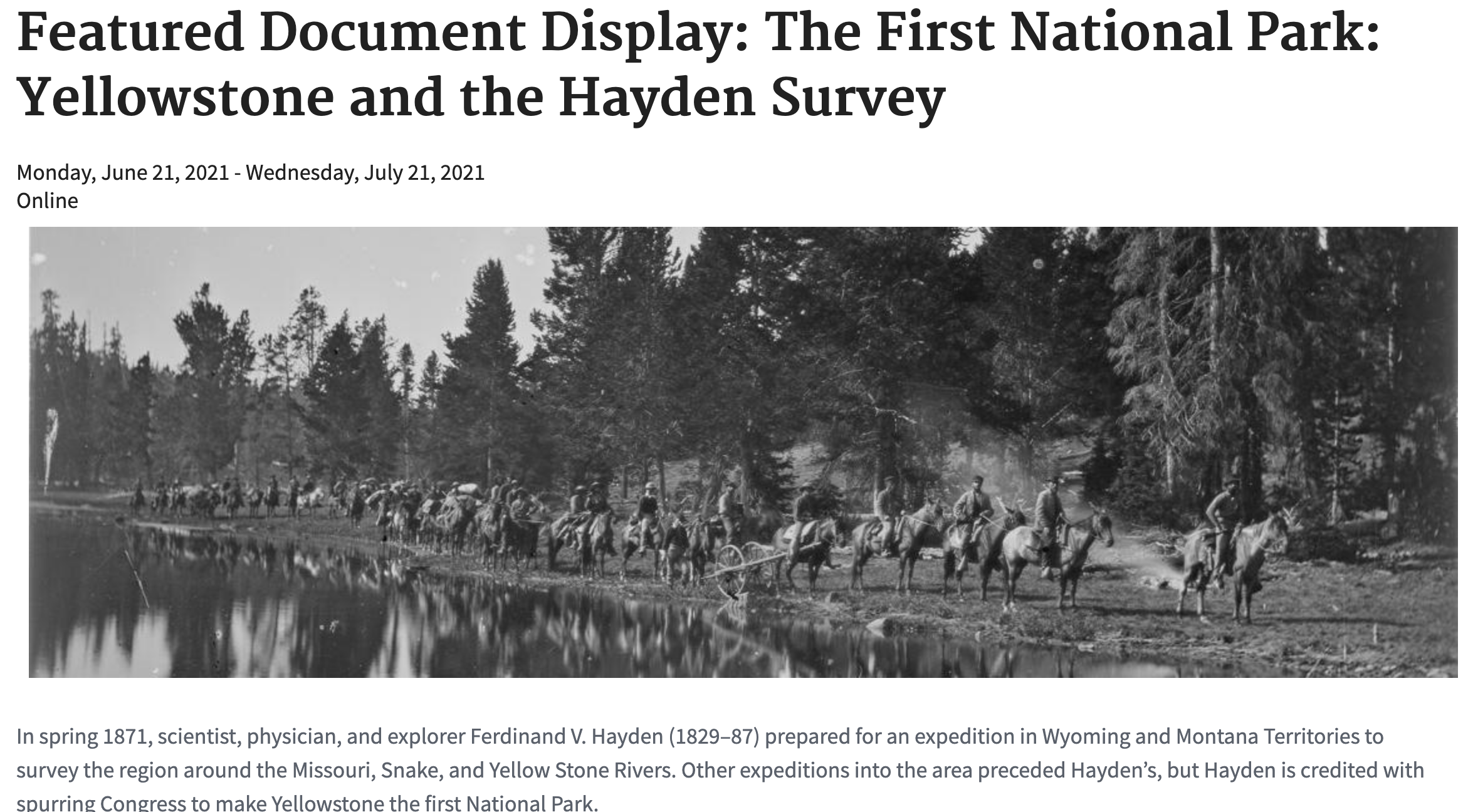

Hayden leading his team

Ferdinand V. Hayden, the director of the U.S. Geological Survey, a division of the U.S. Department of the Interior, was a scientist, physician, and explorer whom Congress commissioned to survey the Missouri, Yellowstone, and Snake Rivers in the western United States. On June 1, 1871, he led his team of guides, hunters, scientists, one photographer and one artist, mule drivers, and doctors out of Fort D. A. Russell, Wyoming Territory, located where present-day Cheyenne now is.

Surveying in the west

Equipped with twenty-seven horses and twenty-one mules, five mule-drawn wagons, two horse-drawn ambulances, piles of tents, stoves, and scientific equipment, the expedition traveled through Utah and Idaho and then into what is now known as Paradise Valley.They stayed in what is now Yellowstone National Park from July 21 until August 8, 1871, surveying, recording their observations and findings, gathering samples, sketching, painting, and photographing the wonders around them. The party worked its way back down to Fort Bridger, in what is now Unita County, Wyoming, on October 2, 1871, where Hayden disbanded the group.

Artist Thomas Moran

Thermal features in Yellowstone

Three of the members of the survey in particular contributed to the report that was instrumental in persuading Congress to set aside the Yellowstone region as the nation’s first national park — Hayden, who composed the meticulous and lengthy record; William Henry Jackson, who shot the stunning black-and-white photographs that he created on glass-plate negatives mounted on massive cameras; and Thomas Moran, whose astonishing sketches and paintings of the thermal features, waterfalls, rivers, and lakes brought Yellowstone straight into the halls of Congress.

Revisit last year’s featured document display on the Survey

But Hayden was also shrewd enough to present his report to people who would be sympathetic to his cause — his supervisors in the Department of the Interior, Congressmen, Senators, and anyone else who lent him a sympathetic ear. He published articles about his expedition’s findings in important national magazines and lobbied tirelessly for the establishment of Yellowstone National Park. There is absolutely no doubt that the Hayden Survey brought the nation’s first national park to fruition.

Can you imagine what Yellowstone and the west looked like 150 years ago? No need!

Over 1,100 photographs were taken during the survey. The photos have been digitized and are viewable online.

National Archives Identifier: 516606

“Moran’s Painting”

Moran’s painting

Source: National Park Service

Thomas Moran, who was born in Bolton, Lancashire, England, in 1837, came to Kensington, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia, as a child with his family. He apprenticed as a teenager with an engraving firm in Philadelphia, but he found the work tedious, so after three years, he withdrew and went to work as a painter in his brother Edward’s studio. In 1861, the two of them went to London to study the work of J. M. W. Turner, an English artist renowned for his moody marine paintings.

Hayden’s Letter

In 1871, when Ferdinand V. Hayden invited Moran to go with him on the survey of the Yellowstone region, Moran leapt at the chance. Moran and photographer William Henry Jackson became fast friends on the trip, working closely to document the territory they were passing through. Their work contributed greatly to the significance of Hayden’s final report and to the success of the appeal for the establishment of Yellowstone National Park.

But his trip to Yellowstone was also a personal turning point for Moran. When he got back to his studio in New York, he was absolutely burning up with inspiration, as he explained to Hayden in this letter in the holdings of the National Archives.

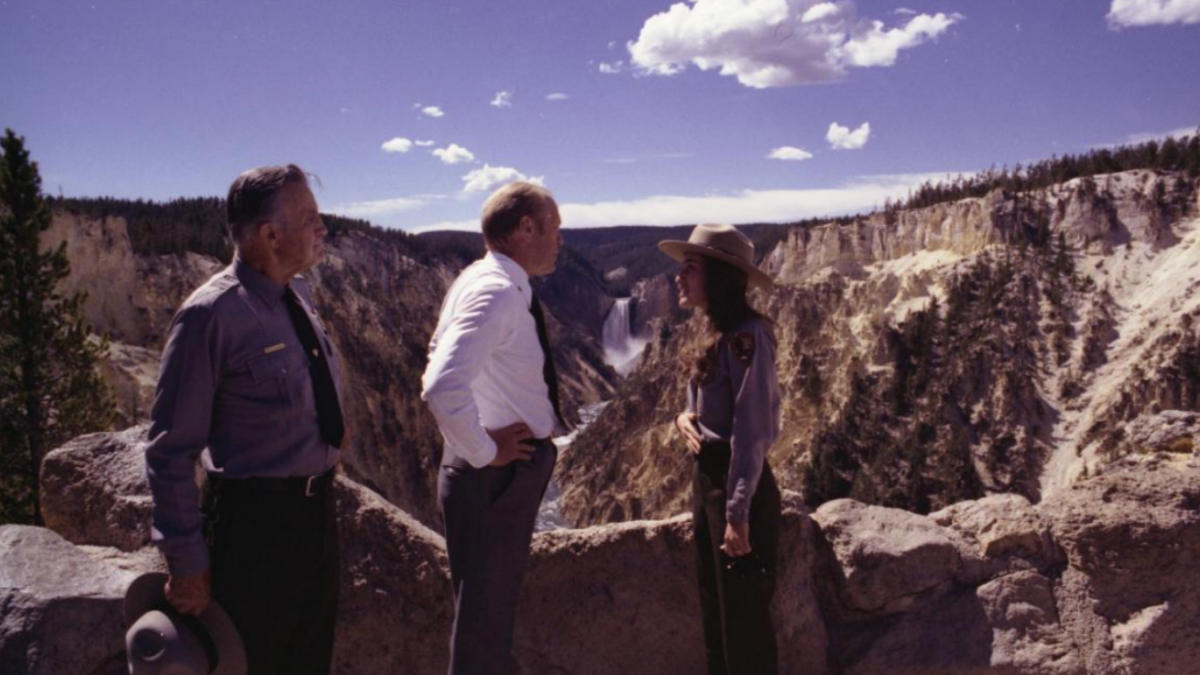

William Henry Jackson’s photographic perspective of the canyon

National Archives Identifier: 516694

He rapidly completed a monumental painting that he titled The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, which Congress bought from him shortly after it had passed the legislation that created Yellowstone National Park in 1872. The painting is now in the collection of the U.S. Department of the Interior and is on long-term loan to the Smithsonian American Art Museum. William Henry Jackson photographed the canyon from nearly the same spot—this photograph is in the holdings of the National Archives.

Moran’s Home and Studio in New York

Landmark Nomination

Document p. 383

National Archives Identifier: 75316077

Throughout his long life, Thomas Moran regularly returned to the American West, where he painted scenes in Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon in Arizona, Yosemite, the Grand Tetons, and, over and over again, the cliffs of the Green River in Wyoming, which he had first seen on that initial trip to Yellowstone. His combination house and studio in East Hampton, New York, is on the National Register of Historic Places. Thomas Moran died in Santa Barbara, California, in 1926, at the age of 89.

“How a (Parks) Bill Becomes a Law”

Legislative action to establish Yellowstone National Park was introduced simultaneously in both houses of Congress on December 18, 1871, by Congressman William H. Clagett of Montana Territory and Senator S.C. Pomeroy of Kansas. The report of the House Committee on Public Lands read in part, “The bill now before Congress has for its objective the withdrawal from settlement, occupancy, or sale, under the laws of the United States a tract of land fifty-five by sixty-five miles, about the sources of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers, and dedicates and sets apart as a great national park or pleasure-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” By February 27, the bill had passed both houses and was sent to President Ulysses S. Grant, who signed it into law on March 1, 1872.

Take a closer look at the Act to Preserve Yellowstone

The significance of the establishment of Yellowstone National Park can hardly be overstated. Since then, the total number of national parks in the United States has grown to 423. Furthermore, not only is Yellowstone the first national park in the United States, but it is also the first in the world. Many nations have since followed the U.S.’ example by setting aside areas of important natural beauty and wildlife habitat, including Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, Jasper National Park in the Canadian Rockies, and Torres del Paine National Park in Chilean Patagonia.

One interesting fact about Yellowstone National Park is that from its inception, it was marketed to the public as a pristine wonderland that had never been inhabited by humans—meaning specifically, by Indians. This was a deliberate action on the part of the park’s managers, who believed that people who might be interested in visiting Yellowstone would be frightened by the prospect of Indian attacks. In fact, archeological digs in Yellowstone—which started pretty much as soon as the park was established and have continued to the present day—have proven that humans have lived and hunted in the park for nearly 10,000 years.

“Camping”

Almost from the moment it was created, Yellowstone National Park was under siege from private interests that wanted to cut timber, kill wildlife, build hotels and railroads, and establish concessions within its boundaries. In 1883, the Yellowstone National Park Improvement Company was on the verge of securing a grant from the Interior Department to build a railroad into the park and log, mine, and establish cattle ranches.

But the park was never without allies, and one of the most powerful men in the country, Lieutenant General Sheridan, the commanding officer of the U.S. Army and a hero of the Union Army during the Civil War, was leading the charge to protect Yellowstone in its pristine state. He proposed to President Chester A. Arthur that he take the chief executive on a three-week fishing trip into Yellowstone.

Learn more about Chester A. Arthur’s presidency here

Facial Hair Friday: Rising above party politics

in NARA’s Pieces of History blog

Arthur might have seemed like an unlikely candidate for a long, probably uncomfortable, and possibly even dangerous trip, mainly on horseback, into the wilderness. He suffered from chronic kidney disease that periodically rendered him bedridden, and he was not a rabid political animal— as we have noted before, he only became president because President James Garfield was assassinated.

But Chester Arthur was a fishing fanatic. Truly! He was born in Vermont, he had fished all his life, and he traveled all over North America to fish. In 1880, in Canada, he had caught the biggest salmon ever recorded on a fly. When Sheridan suggested that fish in the Yellowstone River were eagerly waiting to leap onto his hook, Arthur happily agreed to the trip. And he immediately went out and bought $50 worth of new fishing equipment for the trip—almost $1,400 in today’s money.

The expeditionary group, which numbered more than 75 and included a substantial military escort to ensure the President’s safety, traveled to Green River, Wyoming, on the Union Pacific railroad and then left on horseback for Yellowstone, a distance of more than 300 miles, on August 6, 1883. The group enlisted the help of Arapaho guides to cross the Wind River Mountains and reach the park, which they entered on August 23. They exited the park on September 1 and journeyed on to Livingston, Montana Territory—and Arthur fished nearly every day. Chester A. Arthur was the first American President to travel to Yellowstone, and he enthusiastically agreed with General Sheridan that the park’s natural state should be preserved. His trip conclusively put an end to the Yellowstone National Park Improvement Company’s plans for the park.

“New Slogan”

Even though Yellowstone was established in 1872, not everyone was happy about the idea of the natural resources on 2.2 million acres being protected from extraction by private enterprises. After more than a decade of unrelenting poaching and illegal logging in the park, the U.S. government finally sent the army in to establish a fort at Mammoth Hot Springs at the north end of the park in 1886. The army was stationed in the park for twenty-two years, maintaining order and building permanent structures, including barracks and jails for unruly visitors.

Learn more about

Teddy Roosevelt as a “naturalist President”

from the JFK Library

Then, in 1894, Theodore Roosevelt and other members of the Boone and Crockett Club, one of the earliest conservation organizations in the United States, succeeded in getting the Lacy Act passed, which protected the birds and animals of the park and empowered the army to seize weapons and prosecute crimes committed in the park. The Lacy Act effectively ended poaching and other criminal acts in the park and protected the wildlife and natural features.

Roosevelt Arch, which stands at the northeast entrance to Yellowstone at Gardiner, Montana, was named for the President because he happened to be vacationing in the park while it was under construction. Built of columnar basalt and standing fifty feet tall, the arch is purely decorative.

How was Yellowstone honored on its last major anniversary?

Read Bill Clinton’s words from the 125th.

But Teddy wasn’t finished. Over time, he earned himself the nickname “the Conservation President.” The National Park Service was not created until 1916, well after the end of his second term as President in 1909, but he nevertheless created five new national parks: Crater Lake, Oregon; Wind Cave, South Dakota; Sullys Hill, North Dakota; Mesa Verde, Colorado; and Platt, Oklahoma. Furthermore, under the authority of the Antiquities Act of June 8, 1906, Roosevelt established four national monuments: Devils Tower in Wyoming; El Morro in New Mexico; Montezuma Castle in Arizona; and Petrified Forest in Arizona. He also protected a large portion of the Grand Canyon in Arizona.