More than an Address

We hope you dug into the 1950 Census after last week’s newsletter inspiration. As the public collectively sifts through the mountain of documents, a significant finding may be the addresses of their family members. Beyond a person’s name, their address gives us insight into our past. Knowing what city they lived in, their neighborhood, and details about their immediate surroundings can unlock a treasure trove of information. Maybe you could travel to that same neighborhood, walk the same streets, or visit an old family home.

But how did your family end up living in that neighborhood? The 1950 census provides unique insight into this question. It was taken in the midst of an era of great change, migration, and prosperity that dramatically altered how we lived. With the postwar construction boom, suburban neighborhoods popped up for the first time. More people than ever owned their own homes, and the Baby Boomers were being born, becoming the largest generation ever up until that time.

The security of home ownership and the coveted suburban lifestyle were not distributed equally. As in many other times in U.S. history, people of color were unable to fully share in the success of the post-World War II society and were quite literally “drawn out” of desirable living areas. Although the 1950s were prosperous times, the policy choices made during this era affected housing, education, and many other facets of life through contemporary times.

The Archives has the records to help us understand this complex and consequential period for homeownership. What better way to recognize Fair Housing Month than by highlighting the origins and context found in the Archives’ holdings?

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Color-coded Inequity

“Location, location, location” is a mantra of the real estate profession. While today a “good location” might mean proximity to local schools or a popular downtown, its meaning previously referred to who you were living near, not what.

The year 1933 was in the midst of the Great Depression, when the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) was established. Originally, its purpose was to help homeowners who were in danger of default or foreclosure. It was a New Deal program that attempted to establish secure, government-backed mortgages and loans as opposed to locally offered short-term loans that required huge lump sum payments at the end. HOLC started with a noble goal, but the program had disastrous consequences for equity in housing.

maps here

Residential Security Maps, 1933 – 1939

Source: National Archives Catalog

Record Group 195:

Records of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board

HOLC categorized neighborhoods based on the risk of making loans for those properties. Each neighborhood was assigned a color and outlined on a “residential security map.” Green was the “best,” blue meant “still desirable,” yellow was “definitely declining,” and red indicated “hazardous.” Because housing, like many other aspects of American life, was deeply segregated, areas with high populations of minorities and immigrants were often assigned yellow and red categories. When these families attempted to purchase homes or secure loans in their neighborhoods, they were charged significantly higher interest rates for being in “risky” neighborhoods. Conversely, if they attempted to buy properties in green or blue areas, the fact that they were from red neighborhoods often meant they were denied the necessary loans.

Document outlining redlining practices

National Archives Identifier: 85713724

Taking its name from the red color of hazardous neighborhoods on the map, this practice became known as “redlining.” It artificially devalued properties in certain locations while keeping immigrants and people of color confined to lower-value neighborhoods. Things became even more inequitable during the post-World War II era, when middle-class white families were able to leave the city and move out to the suburbs, a phenomenon known as “white flight.”

Redlining only grew worse after HOLC ceased operations in 1951. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) outright refused mortgages to Black families, believing that allowing them to move into desirable neighborhoods would devalue the properties in the blue and green areas that the FHA had invested in. Until the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968, the FHA’s guidelines allowed and encouraged discriminatory lending.

An Attempt at Fairness

The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was one of the most consequential events of 1968. On the heels of this tragedy, President Lyndon Johnson, with the help of the NAACP and famed advocate Clarence Mitchell, saw an opportunity to advance Civil Rights legislation that had been languishing in Congress for years: the Fair Housing Act.

Clarence Mitchell

Richard Nixon stands with George Romney in Detroit

National Archives Identifier: 16916188

Dr. King was killed on April 4, and by April 11, Congress had passed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, complete with Title VIII, also known as the Fair Housing Act. Its goal was to end the discriminatory lending practices of the Federal Housing Administration and provide minorities, especially African Americans, opportunities to purchase homes. This was especially important for Black veterans, who were met with housing discrimination upon their homecoming after both World War II and the Vietnam War.

Your Right to Fair Housing: What Does Your Congregation Need to Know?

Source: Obama White House Archives

Despite the passage of the Fair Housing Act, housing remained strictly segregated. President Nixon led the first administration tasked with its enforcement, and he tapped George Romney to lead the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Romney advocated for a policy called “open communities,” which would use the authority of the act to encourage African Americans to move to the suburbs, but that plan met with hostility, and Nixon did not move forward.

Reagan’s Remarks on Signing the Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988

Source: Reagan Library

President Ronald Reagan strengthened the act in 1988 when he signed amendments to prohibit housing discrimination based on disability or family status (like the presence of children in a home). The amendments also gave HUD greater authority to enforce the act and established a discrimination complaint process through the Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity.

The 1988 amendments, like many other issues of the time, were a topic of discussion for Senator Ted Kennedy and his usual sparring partner, Senator Al Simpson. Here they comment on how a bipartisan compromise was reached:

September 29, 1988

Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988

Source: Kennedy Library

Public Housing, Public Perceptions

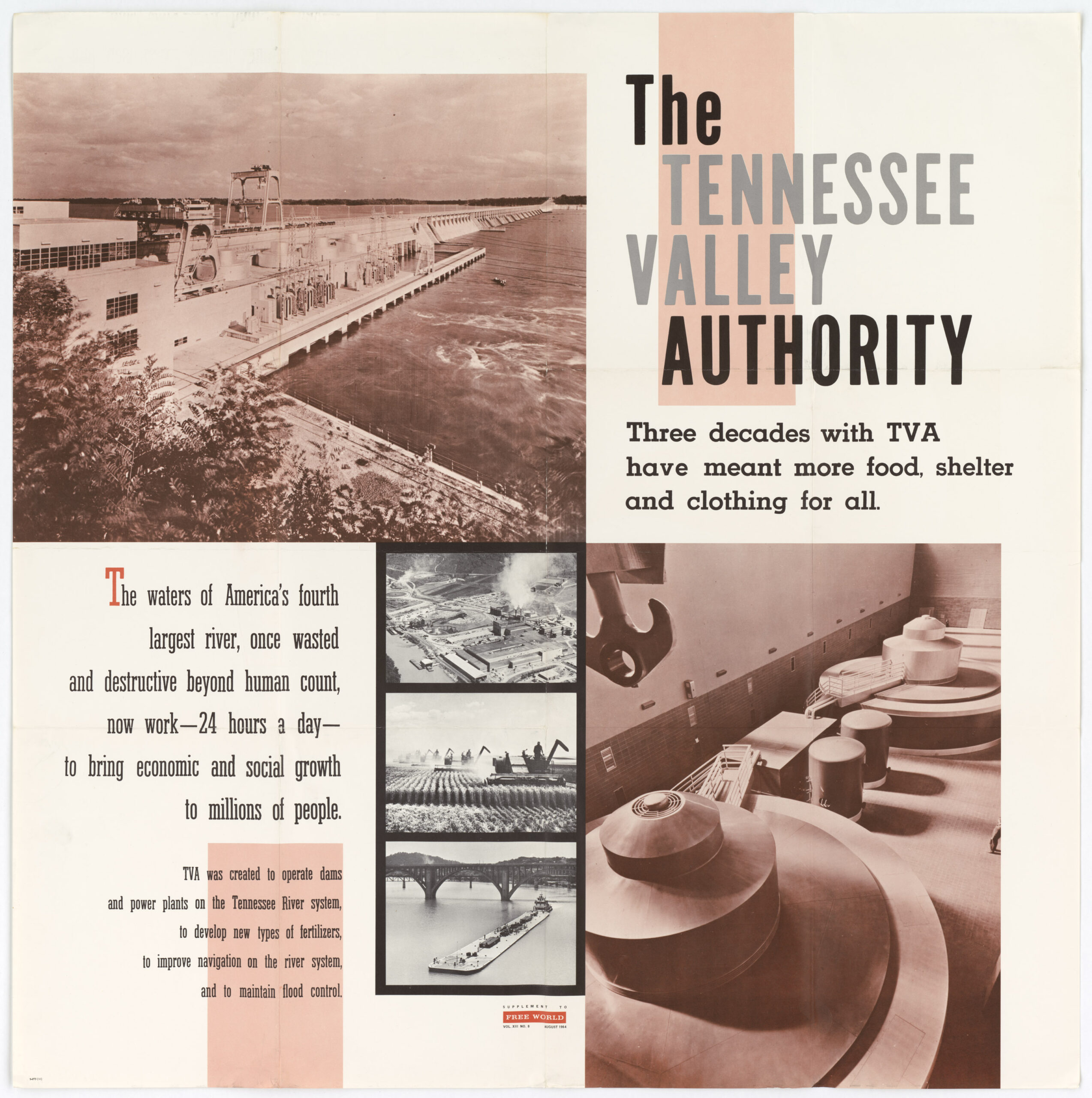

Tennessee Valley Authority

National Archives Identifier: 6949287

TVA Home Planning Center

National Archives Identifier: 653762

TVA-build elementary school specified for “Caucasian” only

National Archives Identifier: 280284

When it comes to the history of public housing, our individual conceptions are likely far from reality. During the Great Depression era, only the truly affluent could afford to purchase homes. Even if middle-class families did have the means, there was such a low supply of housing that it was often impossible anyway. The New Deal sought to combat two different problems at once: it used initiatives like the Tennessee Valley Authority and Civilian Conservation Corps to put people to work and to create more affordable housing.

The first housing projects were dedicated specifically to middle-class white families, and the rules were strict. In fact, there was a long list of disqualifying factors such as failure to provide a marriage license, misbehaving children, or even lack of sufficient furniture. In 1940, the Lanham Act was passed to create more public housing dedicated to those in the defense industry as the country geared up for war. Thousands of units of housing were built to accommodate them.

Housing Projects

1937 – 1941

Record Group 196:

Records of the Public Housing Administration

Housing and Mortgages

Source: National Archives Catalog

Like other types of housing, public housing was deeply segregated, and at first, not even open to Black Americans. As the concept of public housing developed and the NAACP challenged the exclusion of African Americans, regulations were established so that the makeup of individual public housing projects had to reflect the existing racial makeup of the communities. But as the HOLC maps featured in our first story show, that simply led to more segregation.

Read the full Kerner Commission report here

Source: Kennedy Library

Eventually, greater inequities in both income and the housing market changed public housing from affordable housing for the middle class to housing for low-income individuals and families. The deterioration and lack of investment in public housing projects became a Civil Rights issue in the late 1960s, when poor conditions led to protests and riots. President Johnson signed an Executive Order that created the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (the Kerner Commission) to address this problem. Their report’s conclusion was, “Our Nation is moving towards two societies, one black, one white separate and unequal.”

Neighborhood Schools

What does your neighborhood school have to do with housing? Most students in the U.S. go to school in close proximity to their homes. But when neighborhoods are sharply divided between Black and white, schools start to look that way too. Even though Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka desegregated schools, it didn’t desegregate neighborhoods.

That happened with the 1972 ruling in Milliken v. Bradley, which said that busing students across district lines for the purpose of integrating schools was constitutional. The ruling met with extreme opposition, and tensions were so high that advocacy organizations like Freedom House began publishing resources for Black families with school-aged children.

This booklet, printed in 1975 for students in Boston, contains information to help Black families navigate integration into white schools. Sadly, it mostly focuses on how Black children were targeted and unfairly disciplined. Some of the advice includes:

- advising Black students to put their sides of incidents in schools in writing;

- outlining what a “fair disciplinary hearing” should look like, and informing students of their rights; and

- how to advocate for yourself if police or administrators want to search your locker.

The end of the pamphlet comes with this warning:

A Guide Booklet Prepared Especially for

Students and their Parents

to Help Them with

School Problems and the Law

National Archives Identifier: 12161204

Joining the Cabinet

Robert C. Weaver works at his desk in April 1942

Source: Library of Congress

Throughout the twentieth century, housing was becoming a bigger issue for Americans. The country had faced a lack of supply for decades,whether because of the Great Depression or the growing families of the Baby Boomer generation. At the conclusion of World War II, housing was becoming more accessible to middle-class families, and more people owned their own homes than ever before.

Swearing In of Robert C. Weaver as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development

National Archives Identifier: 2803409

This meant an expansion of the government’s role in housing, and in 1965, the Department of Housing and Urban Development Act moved HUD to a cabinet-level position. The first HUD secretary, Robert Weaver, was appointed by President Johnson.

The Crisis

in the American Experience Newsletter

February 8, 2022

Weaver was the first Black cabinet secretary, and he had a long history of housing activism for the Black community. He published articles in W. E. B. Dubois’s paper, The Crisis, (throwback to our Black History newsletter for a refresh!), which pointed out inequities in housing between Black and white communities and argued for a greater supply of housing for Black Americans.

In the 1930s as an advisor to FDR, he implemented a housing plan that provided aid to local housing agencies, bringing down the cost of rent from an average of $19 per month to $16 per month. The HUD building in Washington, D.C., is named in honor of Weaver.

Finding Place for the Negro: Robert C. Weaver and the Groundwork for the Civil Rights Movement

in NARA’s Prologue Magazine

Census programming is made possible in part by the National Archives Foundation

through the generous support of Denise Gwyn Ferguson.