Archives Experience Newsletter - February 8, 2022

An Ongoing Revolution

Our nation was born of a revolution. But even after the initial victory and decades passed, the words of the Declaration of Independence, “…that all men are created equal,” have yet to become a full reality for all.

There has never been just one American Revolution. The Founding Fathers of one era marched as an army against an empire. They gave way more than one hundred years later to the Founding Mothers who marched tirelessly to secure equality of voice through the right to vote.

While all this was happening, there was a parallel reality. The Black community, denied basic human rights until President Lincoln ended slavery, struggled to achieve the same recognitions and protections. One hundred years after the Civil War and many marches later, the Civil Rights movement bore fruit in the form of new laws that started to close the gap toward equality. As a nation, we continue to strive toward a more perfect union. I encourage you to listen to the words of John Lewis as he echos this sentiment.

National Archives Foundation Fund for Rights and Justice (6 min)

This week’s newsletter continues our celebration of Black History Month by highlighting the effort of the Black leaders and organizations whose work has brought us closer to the promises of a more equal, fair, and just nation for all.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

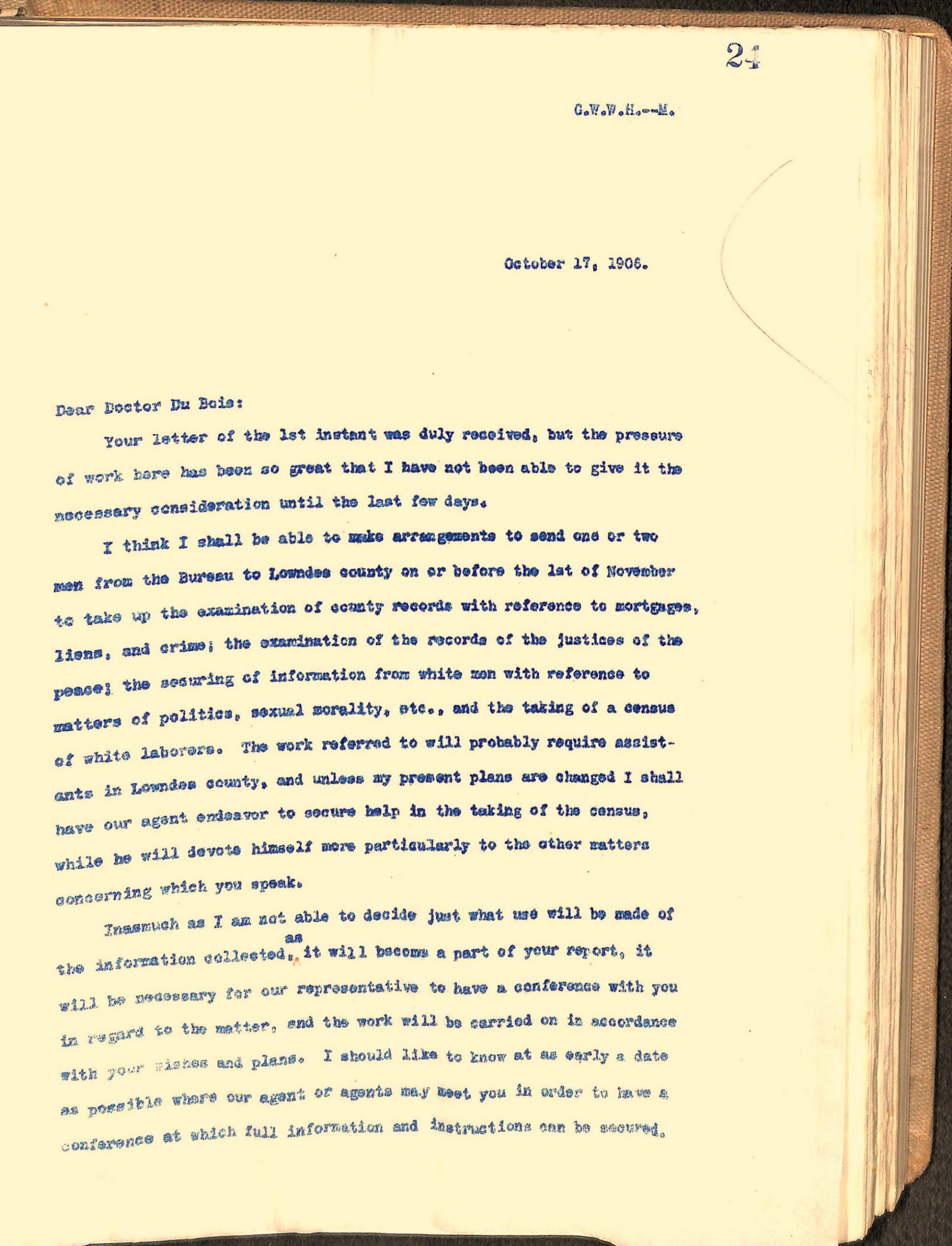

The Crisis

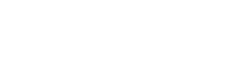

Learn more about W.E.B. DuBois’s home

National Register of Historic Places

National Archives Identifier: 63793639

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was one of the leading lights of the very early movement for Black Civil Rights in the United States. Born shortly after the Civil War in 1868 in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, he was extremely well educated, attending the local integrated public school. He went on to study at Fisk University, a historically black college in Nashville, Tennessee, which his neighbors in Great Barrington paid for. Although he did report having experienced some incidents of racism as a child, he was not subjected to systemic racism and discrimination until he lived in Nashville. He did graduate work at the University of Berlin and at Harvard University, where, in 1894, he became the first Black American to complete a doctorate. The title of his dissertation was The Suppression of the African Slave Trade in the United States of America: 1638–1871. He was not yet thirty years old. In 1884, DuBois worked with Carroll D. Wright, Commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, to help paint an accurate picture of Black life in America.

W. E. B. Du Bois, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the Study of Black Life

on the Rediscovering Black History Blog – Say It Loud

Du Bois taught at Wilberforce University in Ohio for two years and then at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. It was here that he began to formalize his opinion that Black Americans should not aim to integrate into white society. In 1897, he accepted a position at Atlanta University, where he came face to face with the worst practices of the Jim Crow South. He quickly found himself at odds with Booker T. Washington, who advocated an accommodationist position rather than confronting racism outright.

In 1903, Du Bois published one of his most famous works, a collection of fourteen essays titled The Souls of Black Folk. In the introduction, he stated unequivocally, “[T]he problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line.” This was a position from which Du Bois never wavered throughout his long and prolific life.

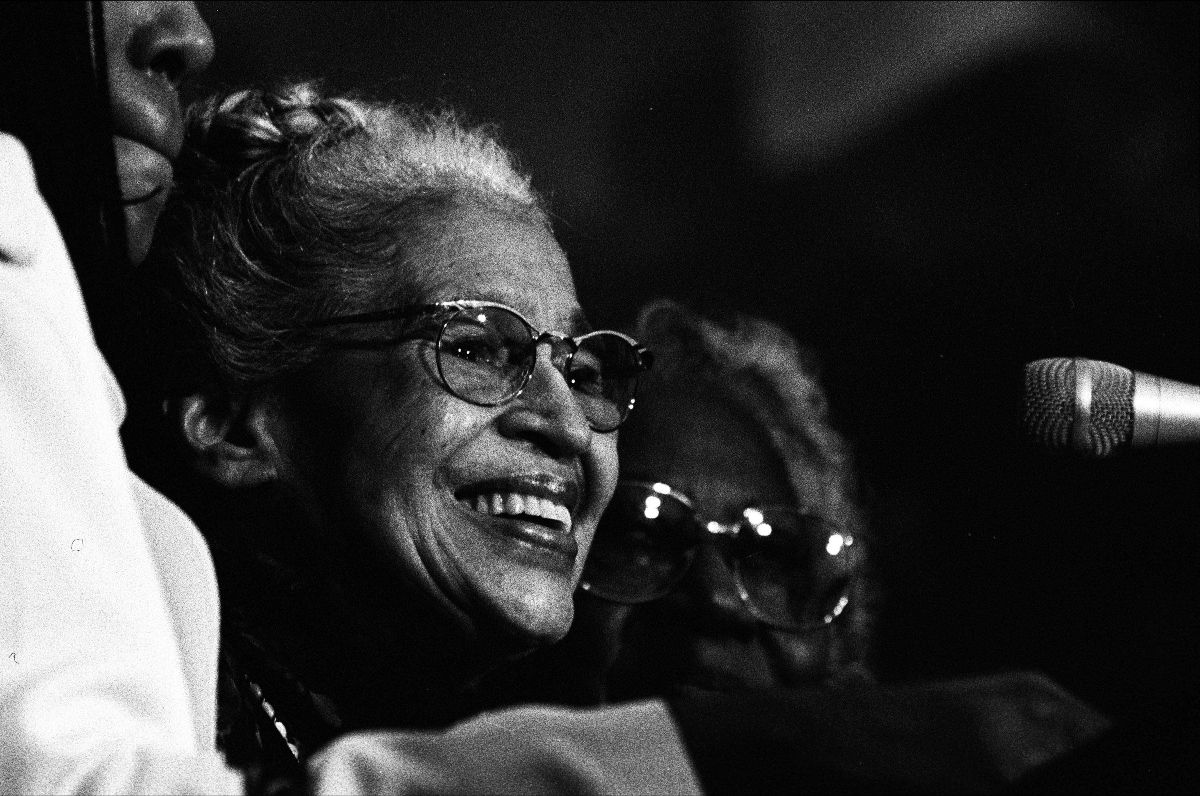

Du Bois was instrumental in the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1910, an organization that exists to this day. He accepted the position of director of publicity and research of the organization in 1910, resigned his position at Atlanta University, moved to New York City, and took on the editorship of the NAACP’s flagship publication The Crisis. From this position, he critiqued Jim Crow and the many harmful stereotypes and caricatures of how Black people were presented at the time.

Du Bois considered himself a socialist, and he often found himself in uncomfortable positions because, for instance, he supported unions but opposed union leadership because Blacks were barred from membership. The same was true of his stance on women’s rights—he supported women’s right to vote, but the leaders of the suffrage movement refused to support the right of Black people to vote.

Starting in 1910, Du Bois fought racism and social injustice from his bully pulpit of The Crisis, reporting on race riots, lynchings, discrimination in government hiring, voting rights, and unfair working conditions. When he got crosswise with Walter Francis White, who became president of the NAACP in 1931, Du Bois resigned and returned to Atlanta University. There, he continued to write, publish, and advocate on behalf of Black people everywhere. He opposed the United States’ participation in World War II and became a more avid anti-war advocate in the years after that conflict ended. He was critical of both capitalism and communism. In 1951, the U.S. Justice Department charged him and his newly founded Peace Information Center with being agents of a foreign government. The case was dismissed as soon as Du Bois’ attorney advised the judge that Albert Einstein was prepared to testify on Du Bois’ behalf.

The government had lost its case against Du Bois, but that didn’t stop it from confiscating his passport and keeping it for eight years. Once he finally retrieved it, Du Bois and his wife took a trip around the world. In 1960, at the age of 93, he joined the Communist Party and traveled to Ghana. He stayed there, working on the Encyclopedia Africana, a comprehensive work about the African diaspora. While he was there, the United States refused to renew his passport, so he became a citizen of Ghana. He died and was buried there in 1963 at the age of 95.

An Ideology Unfinished

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1925) played a prominent role in the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. The spokesperson of the Nation of Islam, a Black Muslim religious organization, Malcolm X was the second most recognizable member of the organization after its leader, Elijah Muhammad.

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination

National Archives Identifier: 73920634

Malcolm Little began life as an impoverished child in Omaha. Because of racist threats against his father, the family moved to Lansing, Michigan, where his father Earl died when Malcolm was six and his mother Helen was left to care for seven children on her own. When his mother was committed to the state insane asylum, the children were separated and sent to foster homes. Eventually, Malcolm went to live with his half-sister in Roxbury, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston, at the age of fourteen. He soon began committing burglaries, dealing drugs, gambling, and pimping.

In 1946, Malcolm was arrested, convicted, and sentenced to eight to ten years for breaking and entering and larceny at Charlestown State Prison. It was there that despite his disdain for organized religion, he was converted to the Nation of Islam. When he was released in 1952, he embraced the religion fully, along with its separatist ideology and belief that Black people should not just be equal to white people, but that they were superior. Bolstered by Malcolm X as their spokesperson and the new converted heavyweight champion boxer Muhammed Ali (formerly Cassius Clay), membership in the Nation of Islam skyrocketed.

National Archives Identifier: 7840017

Malcolm X was outspoken and not inclined to pull any punches with the press or the police. Tall, charismatic, and impeccably dressed, he did not advocate armed rebellion against white society, but he did state that Black people needed to be prepared to defend themselves should white people, including law enforcement officers, attack them.

By the early 1960s, however, Malcolm X became disturbed when he began hearing rumors that Elijah Muhammad was having extramarital relationships with young female members, which was strictly forbidden by the organization’s teachings. In 1964, Malcolm X left the Nation of Islam and, in a matter of weeks, became a member of the Sunni Muslim faith. He then traveled in April 1964 to Saudi Arabia on a pilgrimage to visit Mecca. It proved to be a turning point for the man and his faith.

in NARA’s African American Heritage Resources

“My pilgrimage broadened my scope,” Malcolm told Alex Haley, the coauthor of The Autobiography of Malcolm X. “It blessed me with a new insight. In two weeks in the Holy Land, I saw what I never had seen in thirty-nine years here in America. I saw all races, all colors,—blue-eyed blonde to black-skinned Africans—in true brotherhood! In unity! Living as one! Worshipping as one!”

Malcolm X returned from Mecca a changed man, believing that Islam could be the instrument to achieving true unity among all people the world over. Unfortunately, he did not live to see his dream fulfilled. On February 21, 1965, at the Audubon Ballroom in New York City, Malcolm X was gunned down by an assassin who was a member of the Nation of Islam. Malcolm X was thirty-nine years old when he died.

An Imperfect Messenger

National Archives Identifier: 596069

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an organization devoted to African American civil rights that is based in Atlanta, Georgia. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was its first president. Since its founding in 1957, the SCLC has endorsed and organized nonviolent, noncooperative direct action to protest racial discrimination and disenfranchisement in the United States, mostly in the South. The conference has organized marches in Albany, Georgia; Birmingham, Alabama; St. Augustine, Florida; Selma and Montgomery, Alabama; Grenada, Mississippi; Jackson, Mississippi; and, famously, Washington, D.C.

The SCLC was also responsible for the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The boycott introduced a new phase of the Civil Rights movement, noncompliance. And although the boycott was started due to the bravery of women like Claudette Clovin and Rosa Parks, the SCLC often downplayed and overlooked the contributions of Black women to the Civil Rights movement or disallowed them from opportunities completely.

Watch our interview from last year with Fred Gray, the lawyer who planned the boycott (1 hour 14 min)

about Rosa Parks

NARA Educator Resources:

An Act of Courage,

The Arrest Records

of Rosa Parks

In 1954, Septima Clark started the Citizenship Schools in the South in partnership with Esau Jenkins. Although the mission of the schools was purportedly to teach Black adults to read and write, the students also studied civil rights, politics, and tactics of struggle and resistance. When the SCLC acquired the schools, Clark became the first woman on the board, and the fights over her tenure then started and never stopped. “We also should heed the words of the Civil Rights organizer Septima Clark who commented that during the ’60s many black men in the movement, ‘just thought that women were sex symbols and had no contributions to make, [and] whatever the man said would be right and the wives would have to accept it,” noted Adele Logan Alexander, an emeritus professor of history at George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

Today, the SCLC is a nationwide organization that continues the legacy of Dr. King while also advocating for the advancement of Black women and girls.

“Good Trouble”

National Archives Identifier: 222097049

National Archives Identifier: 16899041

John Lewis was a young man when he joined the fight for civil rights in the United States. Born in 1940 in Alabama, he co-founded the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and helped organize many important events in the Civil Rights movement, including the Freedom Rides, the 1963 March on Washington, and the Selma to Montgomery Marches. He spoke before Dr. King did at the March on Washington in 1963 and took part in the “Bloody Sunday” Selma March in 1965. Understanding the indelible connection between civil rights and the right to vote, he invested endless hours in voter registration drives in his community.

NARA’s African American Heritage Resources

Lewis was elected to the House of Representatives in 1987 to represent the Fifth District of Georgia. Over the next thirty years, he was reelected eighteen times. Through it all, he never lost his dedication to civil rights. “I have been beaten, my skull fractured, and arrested more than forty times so that each and every person has the right to register and vote,” he tweeted in 2018. “. . . Do your part. Get out there and vote like you’ve never voted before.”

Called by his colleagues the “conscience of the Congress,” Lewis exhorted everyone to get into what he described as “good trouble, necessary trouble.” John Lewis died in office in 2020 at the age of 80.

The Children’s Crusade

National Archives Identifier: 16899060

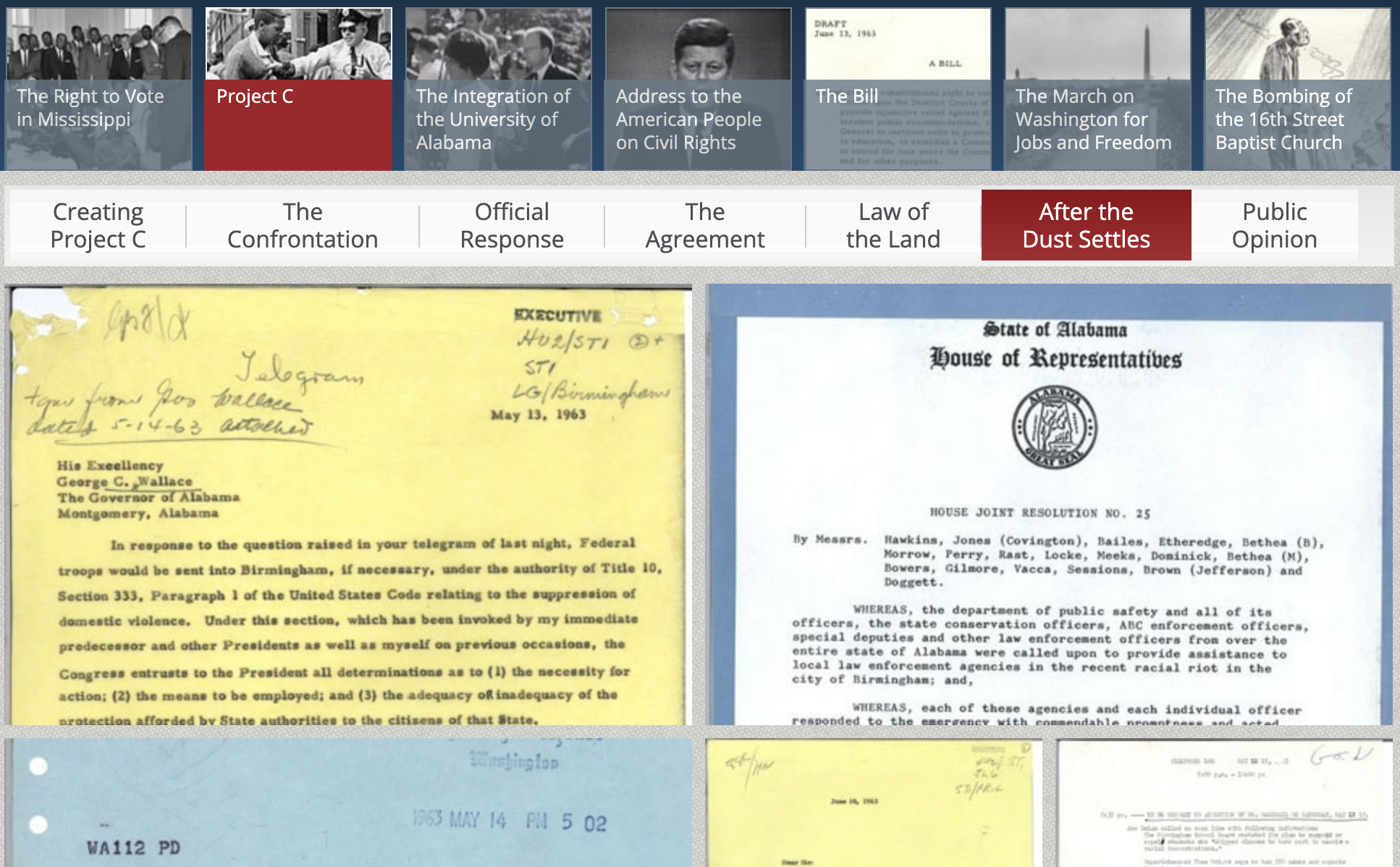

Martin Luther King, Jr., considered Birmingham, Alabama, the most segregated city in the United States. He and Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth organized a series of protests in Birmingham in the spring of 1963, but those efforts had little immediate effect. King was arrested in Birmingham on Good Friday, April 12, and thrown in jail for a week. His “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” which he addressed to white and Jewish clergy members who objected to his tactics in pursuing civil rights, became one of his most famous and provocative pieces of writing.

from the 1963: The Struggle for Civil Rights – Project C at the JFK Presidential Library

While King was in jail, James Bevel, another civil rights organizer, encouraged the young Black people of Birmingham to demonstrate. Starting in May, they marched in the streets. To suppress the demonstrations, Birmingham City Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor sent police out with high-pressure fire hoses and police dogs. The police arrested nearly a thousand young people.

from the JFK Presidential Library

Connor’s efforts backfired, however, when television broadcasts of the violence flashed around the nation and the world. President John F. Kennedy responded by sending several thousand troops to Alabama, and in Washington, he moved to accelerate the passage of a comprehensive civil rights bill.