Archives Experience Newsletter - February 7, 2023

Get in the Game!

Whenever there’s a big event coming up, people will sometimes say, “This is our Super Bowl.” It’s turned into a pretty universal (at least…in America) euphemism for, “This is a BIG deal.” Starting in April, we at the Foundation will begin planning for our annual July 4th celebration, and you’ll hear staff around the office say, “July 4th is our Super Bowl.”

Well, this weekend is the actual Super Bowl, so is there a better topic than the history of football? Luckily, it’s all on display in the Archives exhibit “All American: The Power of Sports,” and now we’re bringing it to your inbox.

In this issue

Rutgers and Princeton, played the first football game in the United States on November 6, 1869…

Second Down

In 1894, the Army-Navy game became so violent that President Grover Cleveland banned the annual contest between the two academies…

Third Down

President Teddy Roosevelt laid down the law: “Football is on trial. Because I believe in the game, I want to do all I can to save it”….

Fourth and Goal

In 1965, the NFL approached the AFL to negotiate a merger…

History Snack

First Down

Next Sunday, February 12, 2023, the Kansas City Chiefs and the Philadelphia Eagles will play for the National Football League championship in Super Bowl LVII at State Farm Stadium in Glendale, Arizona. The game has come a long way since two college teams, Rutgers and Princeton, played the first football game in the United States on November 6, 1869, at Rutgers in New Brunswick, New Jersey. In that game, each team had 25 players, and the rules of their game were based on those of soccer. Since then, the game has evolved from a combination of the rules of both soccer and rugby—although it is fair to say that often there were few to no rules at all, and players rarely wore protective gear.

More colleges joined the intercollegiate competition throughout the 1870s, but the rules of the game remained fluid, and the playing field sometimes looked more like a war zone. In 1873, representatives from Yale, Princeton and Rutgers established the Intercollegiate Football Association (IFA) to create rules for what they called “association football” and schedules for games between the participating universities. Representatives from Harvard did not attend because they were holding out for a different set of rules.

Representatives from Harvard, Yale, Princeton and Columbia met at the Massasoit House hotel in Springfield, Massachusetts to standardize new rules in 1874. At that meeting, Harvard, Columbia and Princeton established the second Intercollegiate Football Association, but Yale did not join the group until 1879, because of a disagreement about the number of players per team. This IFA lasted from the 1877 season until 1893.

Soldiers drafted into WWI work out on base — football and boxing were the most encouraged

(9 minutes 39 seconds, NO SOUND)

National Archives Identifier: 24715, item #47

Second Down

In 1876, a young man named Walter Camp enrolled at Yale. A gifted athlete, Camp immediately excelled in baseball, track and association football. He played halfback on the Yale football team and was captain of the team in 1878. That same year, he began attending the annual meetings at Massasoit House. Called the “father of American football,” Camp immediately began proposing changes to the rules. First, he suggested reducing the number of players from 15 to 11, an idea that was at first declined but was later adopted in 1880, along with his proposals for creating a line of scrimmage and snapping the football from the center to the quarterback. In 1882, he suggested that a team had to move the ball at least five yards within three downs.

After he graduated, Camp went on to coach college teams, starting with Yale, moving to Stanford on the West Coast and then returning to Yale. He was famous for his hard-nosed approach to the game. “Better make a boy an outdoor savage than an indoor weakling,” he said.

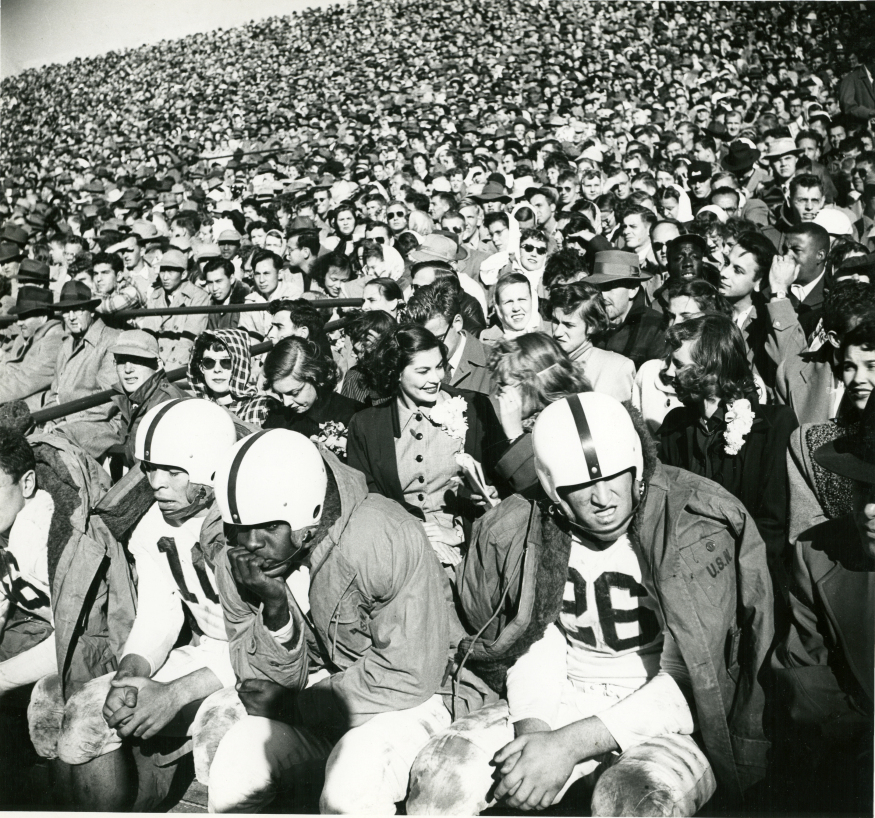

And indeed, Camp’s innovations did nothing to make the game safer. To say playing football in this period was dangerous is an understatement. For the most part, players still weren’t wearing protective gear, including helmets. One particularly dangerous play was called the “flying V,” in which players lined up in a V formation and ran directly at the player on the opposing team who was carrying the ball. In 1894, the Army-Navy game became so violent, with so many fistfights on the field, in the stands and even between high-level members of the military elite who were attending the game—one brigadier general and one rear admiral nearly fought a duel over the game—that President Grover Cleveland banned the annual contest between the two academies.

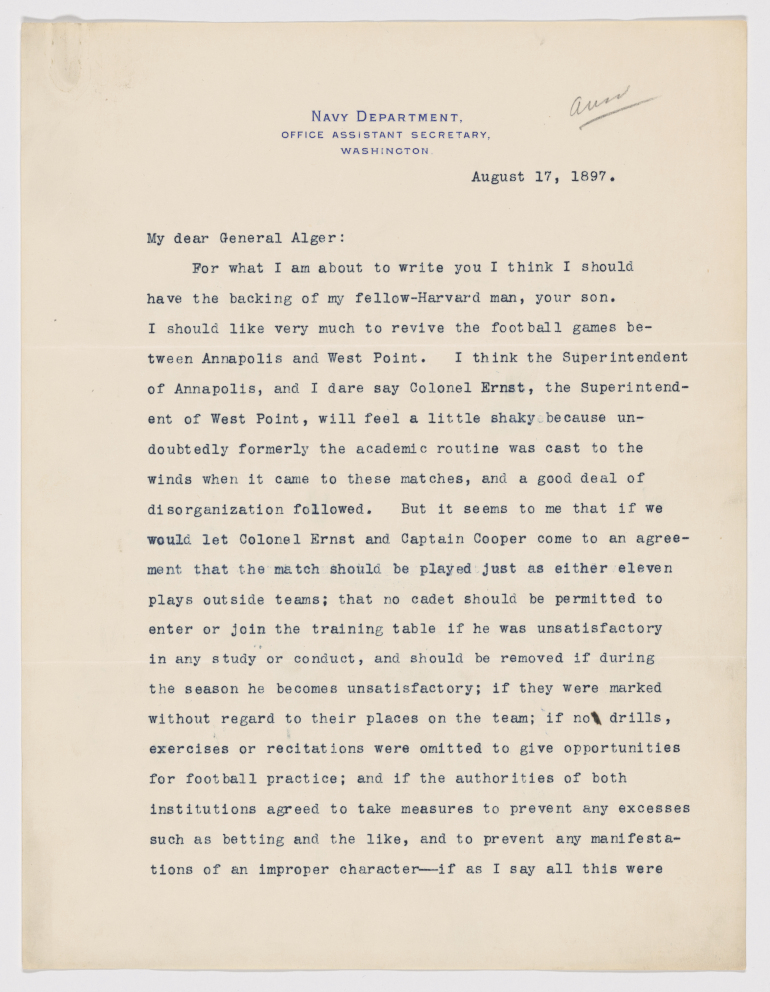

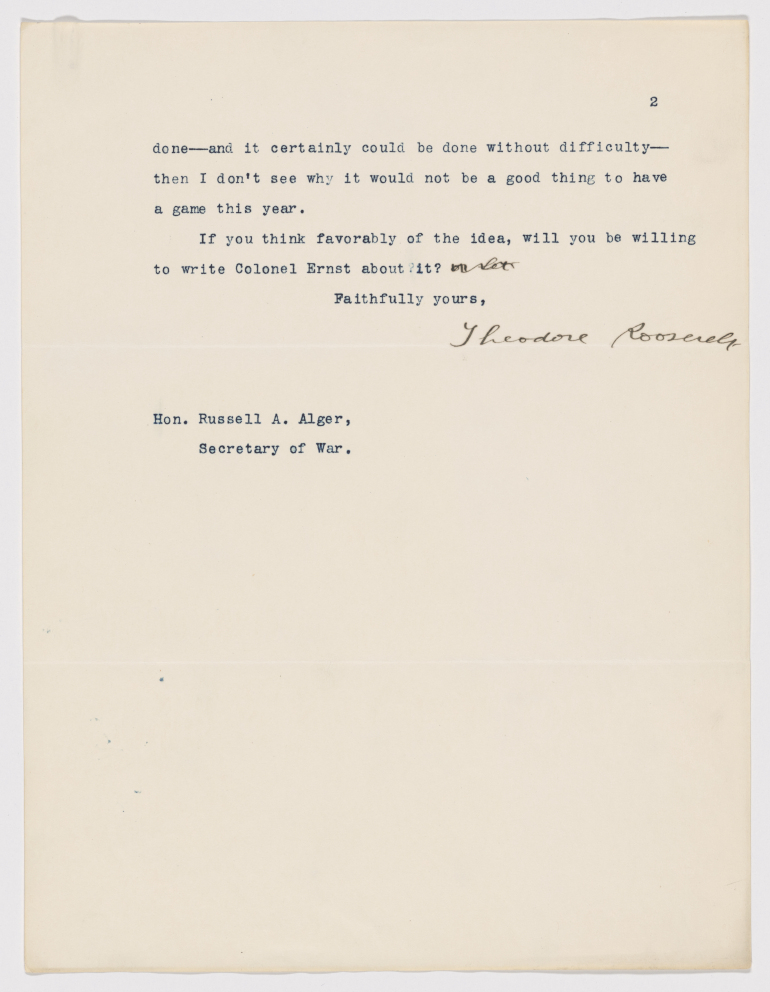

This state of affairs persisted until, in 1897, Vice President Theodore Roosevelt stepped in, petitioning Russell A. Alger, the Secretary of War, to reinstate the game, provided the opposing teams would agree to certain conditions to keep the contest (rather more) civilized. The academies agreed, and the next year, in 1898, the competition began again.

Teddy Roosevelt requests reinstatement of the Army/Navy game, page 1

Teddy Roosevelt requests reinstatement of the Army/Navy game, page 2

Footage of the 1938 Army/Navy game

(8 minutes 49 seconds)

National Archives Identifier: 84439

Third Down

Nevertheless, the mayhem on the gridiron persisted. In 1905, horrified by 18 deaths and at least 159 serious injuries on the football field—and by “serious,” we mean broken backs, broken necks, concussions and internal injuries that resulted from being kicked during pileups on the field—President Teddy Roosevelt called a meeting at the White House with Secretary of State Elihu Root and coaches and athletic directors from Yale, Harvard and Princeton. There, Teddy laid down the law: “Football is on trial. “Because I believe in the game, I want to do all I can to save it. And so I have called you all down here to see whether you won’t all agree to abide by both the letter and spirit of the rules, for that will help.”

The attendees got the message—it was rein in their players, or Teddy would ban the sport nationwide. Sixty-two colleges signed on as members of the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States in March 1906 (renamed the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in 1910). They changed the rules to forbid hurdling, allow the forward pass, create a neutral zone at the line of scrimmage, increase the yards necessary for a first down from five to 10, limit the number of players who could line up in the backfield to five, prohibit hurdling, and establish a penalty system. These changes helped diminish the violence inherent in playing the game. The forward pass also made the game faster and more fun to watch.

Fourth and Goal

All these changes gave birth to the modern era of American football. The professional era began unofficially when Pudge Heffelfinger received $500 on November 12, 1892, to play for Allegheny Athletic Association against the Pittsburgh Athletic Club, but paying players was frowned upon until the establishment of the American Football Association, later the National Football League, in 1920. The association created rules for recruiting and paying players, including prohibiting college players from participating in professional football games. College football remained the main form most Americans enjoyed until 1925, when the NFL’s Pottsville Maroons defeated a team of Notre Dame all-stars in an exhibition game. Once professional football was televised after World War II, it gained a much wider audience.

In 1960, a group of investors wanted to expand the number of professional teams. They got no cooperation from the National Football League and consequently went out on their own, creating the American Football League, which included eight teams, four in the east and four in the west. The NFL assumed that the AFL would soon burn out and consequently chose to ignore it, but the success of teams like the New York Jets, led by quarterback Joe Namath, and televised AFL games that attracted millions of viewers began to give the NFL pause. Bidding wars for star college players immediately ensued between the two leagues. Things were beginning to get out of hand. In 1965, the NFL approached the AFL to negotiate a merger, which was announced on June 8, 1966, to take effect in 1970. The agreement included several provisions, including the initiation of an annual championship game between the two leagues that eventually became the Super Bowl.

Ford helmet in “All American” exhibit

Green Bay Packers letter to Gerald Ford offering him a professional football contract

National Archives Identifier: 6926458

Football had become part of the fabric of American life. A future president, Gerald Ford, participated in football for the University of Michigan throughout his college career, playing linebacker, center and long snapper. Upon his graduation with a degree in economics, the Green Bay Packers offered him a professional contract at $111 per game. Ford turned it down, but he credited playing football with teaching him leadership skills. He continued to attend football games throughout his life and even occasionally joined the huddle on the field.