Archives Experience Newsletter - August 24, 2021

Counting All Voices

Over the past few weeks, Americans have been fascinated by the release of the 2020 census data. (Or, in the exact words of the Constitution, “the actual Enumeration.” ) The public and media have pored over population maps, viewing the changing makeup of our neighborhoods, states, and nation. The impact of the census cascades from how the government distributes funds to states and local communities to the makeup of Congress. The U.S. Census Bureau describes this moment: The census tells us who we are and where we are going as a nation.

But for the armchair family historian who has used census data to conduct research, something’s missing from the 2020 Census news: the details. Where are the specifics that reveal ages, jobs, and other facts people might use to find their relatives? This newsletter will explain.

The Archives is the agency entrusted to preserve these records until they are ready to be fully released – seventy-two years after the collection date. In 2022, the Archives will release the 1950 census. This will help many of us learn about the not-too-distant history of our own families and will reveal a wealth of information about everyday Americans during an iconic era.

The 2022 release isn’t too far off, so let’s limber up those research muscles. We’ve deciphered the details of the decennial census below.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

The Origins of 435

In the United States, the Constitution mandates that a census of the population be conducted every ten years. The census is especially important because the number of people in a state determines how many members that state is entitled to seat in the House of Representatives.

The question of equitable representation was a thorny issue when the First Congress was seated in 1789 because no reliable data existed about exactly how many people were living in the new nation. This problem motivated Congress to draft an enumeration act that established the procedures for counting the population. After prolonged and contentious wrangling, Congress passed the law and sent it to President George Washington for his signature.

It’s no surprise that many people were not happy with the results of the census. Thomas Jefferson and George Washington were both certain the final count was too low, but later censuses confirmed the accuracy of the 1790 data.

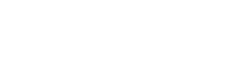

Congress used the results of the successive censuses to increase the number of representatives until 1929, when the Permanent Apportionment Act reassigned that duty to the Secretary of Commerce and capped the number of representatives at 435.

Counting on You

The National Archives is the keeper of all the data from all the censuses ever conducted in the United States, beginning in 1790. The records from 1790 to 1940 are now available to the public.

It might seem like the Archives is running late in releasing census data, but such data are subject to the “seventy-two year rule,” which forbids the government from releasing an individual’s personally identifiable information to any other individual or agency until seventy-two years after it was collected for the decennial census.

Looking at the individual records from the various censuses can reveal a massive amount of very interesting information. In addition to a person’s name and residence, the records often include ages, occupations, the names of other family members, and levels of education.

The National Archives is more than the keeper of these records; its staff members have also put together helpful information and resources about how to search past census records. Whether you’re looking for family history or population data or simply seeking more information about this unique and impactful process, the Archives is the place to go.

Who Wasn’t Counted?

When census takers began enumerating the population of the U.S. for the first time in 1790, they only counted particular groups of people: White male heads of households, free White males over the age of sixteen, free White males under the age of sixteen, free White females, all other free persons, and enslaved persons. Each enslaved person was counted as 3/5s of a person, and Native Americans were not counted at all.

The 3/5s rule was written into the Constitution because representatives of the Northern states, which did not permit slavery, were concerned about guaranteeing equitable representation in the House of Representatives, which is based on a state’s population. At that time, the number of enslaved persons in the South far outnumbered the populations of the Northern states. After the Civil War ended, Congress passed and the states ratified the fourteenth amendment, which stated, “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof” were U.S. citizens. This amendment specifically repealed the 3/5s clause.

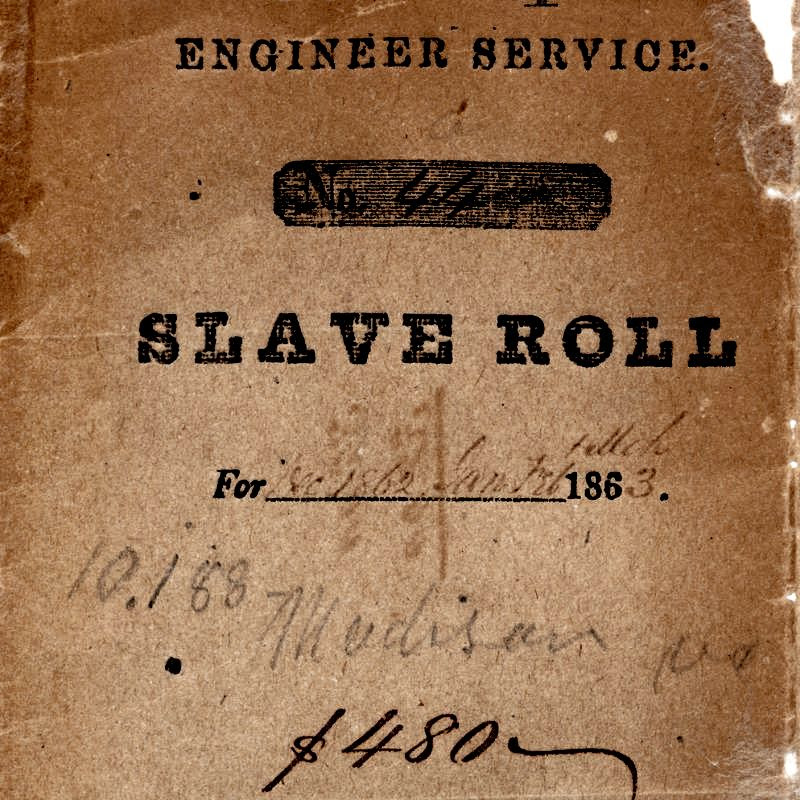

Unfortunately, because the census did not fully or reliably count enslaved Americans, we must often look elsewhere to get a complete picture of their daily lives, families, locations, and other information. One source of data about enslaved persons not derived from censuses is a series of records called the Confederate Slave Payrolls, which list the names of enslavers and their enslaved people whom they loaned to the Confederate Army during the Civil War. These enslaved persons mined raw materials to make explosives, dug trenches for the Confederate troops to fight from, washed their clothes, and cooked their food. The payrolls list the names of the enslavers, the names and home counties of the enslaved, and the amounts their owners were paid for their labor.

Beginning in 1860, a few Native Americans living among the “general population” were counted for the first time, but it was not until the 1900 Census those living on reservations were included in the regular count. Native Americans did not gain full citizenship until passage of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924.

Furthermore, women almost went uncounted in the census. During the debate over the 1790 Enumeration Act, Senator Samuel Livermore opposed using the word “female” in the bill. His reason? He was begging his colleagues to consider how a census taker could “be so indelicate as to ask a young lady how old she was.”

History Snacks

Not Who, but What

In addition to counting people, census takers have recorded information that can help us visualize different facets of daily life in that time period. For the census years 1850, 1860, 1870, and 1889, schedules of statistics are available for agriculture, mortality, and social data such as the value of real estate and average wages for different occupations. For 1935, schedules for statistics are also available about radio stations, banking and financial institutions, advertising agencies, public warehousing, miscellaneous enterprises, and trucking for hire.

Make Yourself Count!

To help persuade Americans to take part in the 1950 census, the Commerce Department created a series of public service announcements to be broadcast on television. The message is the same in all of them – it urges Americans to stand up and be counted – but the varying ways it is delivered reveal a lot about the era. Check out six of the PSAs right in the Archives’ catalogue!