Preserve, Protect, and Defend

Held in the cavernous Rotunda at the National Archives are the Charters of Freedom – the original Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. This is the founding trilogy of democracy in the United States.

The vision, words, intent, interpretation and implementation of these three documents are put to action every single day in every single city and town. From our sidewalks and town halls to our courthouses and military bases, the Founders’ vision for the republic – that was negotiated, haggled over and agreed upon (eventually) – is put to work. Tomorrow’s event will be another example of the enduring permanence of the Constitution.

No quadrennial election is without politics or drama. We have had both over the last year, yet tomorrow the country will pause at noon and watch the next President of the United States assume the role. Each inauguration is historic. They have taken place in New York, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. In Washington, they have been hosted in the Senate Chamber and on the East and West Porticos of the U.S. Capitol, inside the Capitol and at the White House. Tomorrow’s ceremony will not be notable for the location or site, but the country will bear witness as a woman assumes the role of Vice President for the first time – 101 years after women secured the constitutional right to vote.

In the spirit of this week’s page forward in history, we look back at previous inaugurations and presidential history.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

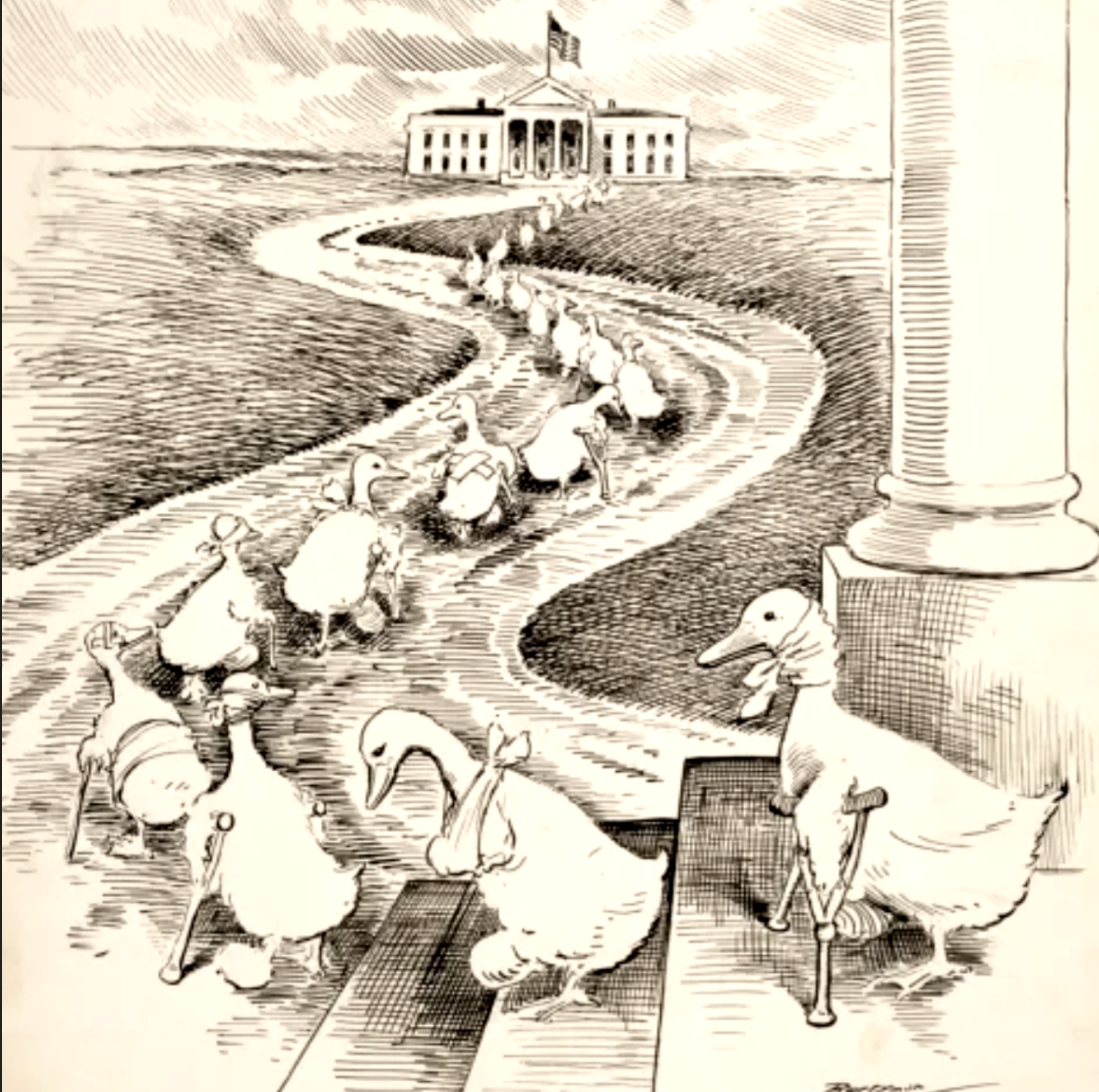

A Duck to Water

Until 1936, the President was sworn in on March 4, as the Constitution mandates. A President who is leaving office is called a “lame duck” during the period from the election until the new President is sworn in because he or she generally can’t accomplish much in that short time. Furthermore, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, news traveled much more slowly than it does now, so the four-month lag between Election Day and the inauguration was not especially troublesome then. That situation had changed by the time Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1860 – news of his victory traveled swiftly, and consequently, nearly all the Southern states had seceded from the union by the time he took the oath of office in March.

The 20th Amendment, which changes the date of the ceremony to January 20, was ratified in 1933 and went into effect for the next presidential election.

Fourth Time’s A Charm

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was an unusual President for many reasons, not the least being that he was elected to the office four times. Consequently, he took the oath of office at four different inaugural ceremonies, the first three of which were conducted at the U.S. Capitol. Because World War II was still raging in 1944, FDR’s fourth inauguration took place very quietly at the White House. FDR was also the first president to take the oath in January rather than March.

MLK and JFK

When he took the oath of office in January 1961, John F. Kennedy was the youngest man ever elected to the presidency. His youth, charisma and eloquence were all powerful attractions, but for much of the presidential campaign, he was running neck and neck with Vice President Richard Nixon.

During the campaign, the nation was being rocked by protests aimed at advancing civil rights, especially in the South. In late October 1960, less than a month before Election Day, Martin Luther King, Jr., was jailed in Georgia for leading a protest in Atlanta. Most of Kennedy’s advisors felt the candidate should not try to intervene—they feared doing so would alienate white Southerner voters. Others argued that Kennedy had to do something, and in the end, he agreed. He called Coretta Scott King, who was pregnant at the time, at her home and offered her his support.

When he was freed from jail, King credited Kennedy with having used his influence to secure his freedom. The election results were extremely close, but Kennedy defeated Nixon by a very narrow margin. Many historians credit Kennedy’s support of King with having won him vital support among black voters across the country. Both John Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., were passionate about advancing the cause of civil rights in the United States, and both were gifted orators.

Kennedy’s inaugural address and King’s “I Have a Dream” speech are among the most frequently quoted speeches in U.S. history.

When he signed the proclamation authorizing the official observance of the Martin Luther King, Jr., federal holiday in 1996, President William Jefferson Clinton noted, “But despite the great accomplishments of the Civil Rights Movement, we have not yet torn down every obstacle to equality.” A great deal of work remains to be done to guarantee every person in the United States the same freedoms and opportunities.

Taft’s Gaff

When you have to give a speech or act in a school play, do you ever worry that you’ll forget your lines? Don’t fret – it’s extremely unlikely you’ll make as big a public gaff as

Chief Justice William Howard Taft did when he administered the oath of office to presidential incumbent Herbert Hoover in 1929. Instead of instructing Hoover to say he would “preserve, protect, and defend” the U.S. Constitution, Taft said Hoover should promise to “preserve, maintain, and defend” it. Considering that Taft had been President from 1909 to 1913 and thus had taken the oath himself, that’s a pretty big mistake. Unfortunately, at the inauguration, you don’t get do-overs.

Lassoing the Cowboy President

No, it wasn’t Wonder Woman – it was cowboy Montie Montana who threw a lasso around President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s shoulders as he reviewed the inaugural parade in 1953. Fortunately for Montana, he had gotten clearance from the Secret Service to pull this stunt.