Archives Experience Newsletter - July 26, 2022

Respect: More Than Just Ramps

Thirty-two years ago today, President George H. W. Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act into law. Modeled after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it gave “equal opportunity” to the disability community for the first time.

This landmark legislation was one of the largest overhauls of policies to impact everyday life in the United States, and it established inclusion and access as an expectation, not an exception.

People with disabilities spent decades pointing out the biases built into their lives and how the freedom to move through a world that was designed for all is fundamental. The law’s passage was just the beginning of building awareness with politicians, the media, and the public – a campaign that continues to this day.

July 26 is National Disability Independence Day. We’re boosting the visibility of disability activism with Archives records related to the landmark ADA, disability activism, and more.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Executive Experiences

Enrolled Bill S. 6 – Education for All Handicapped Children

National Archives Identifier: 6037497

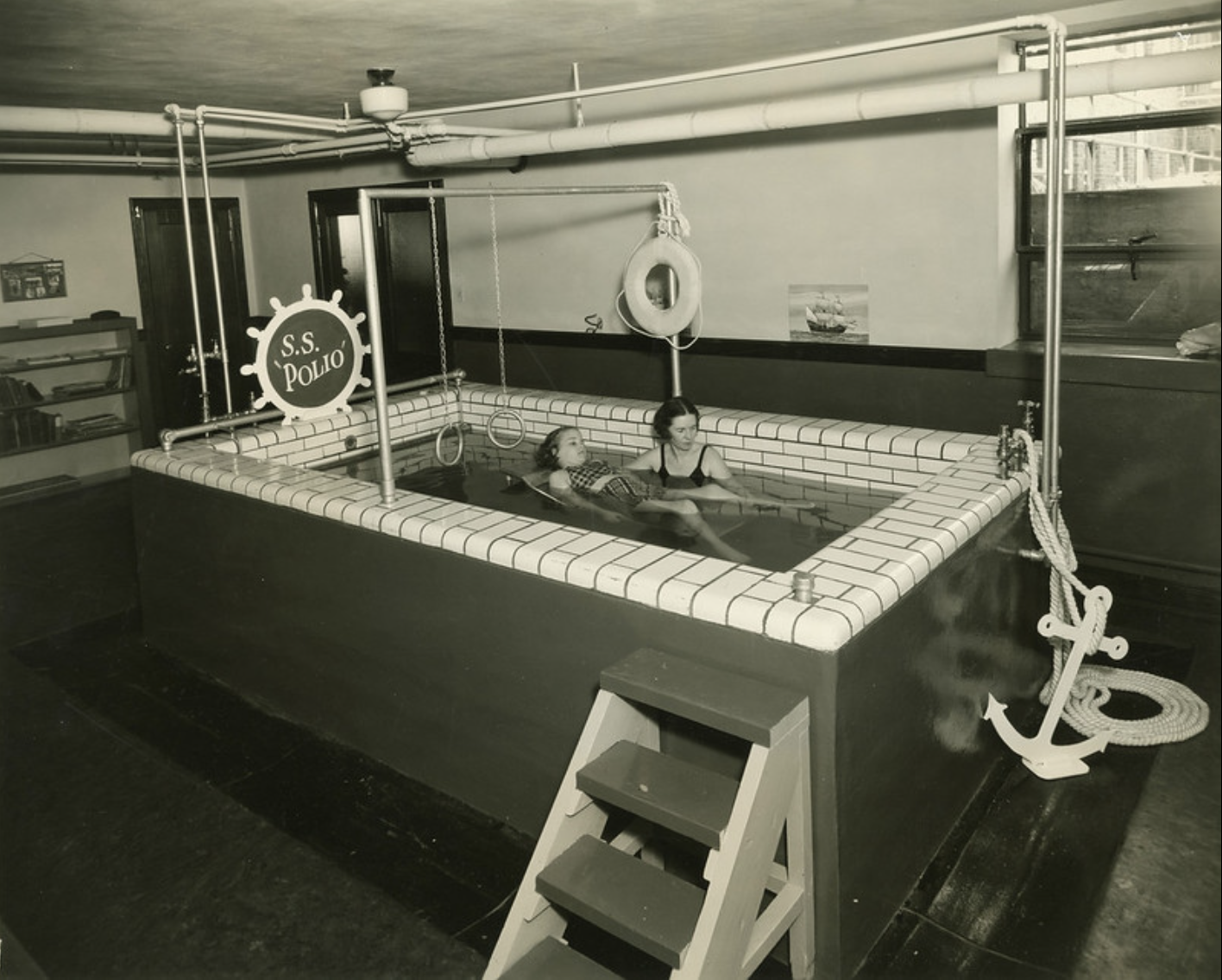

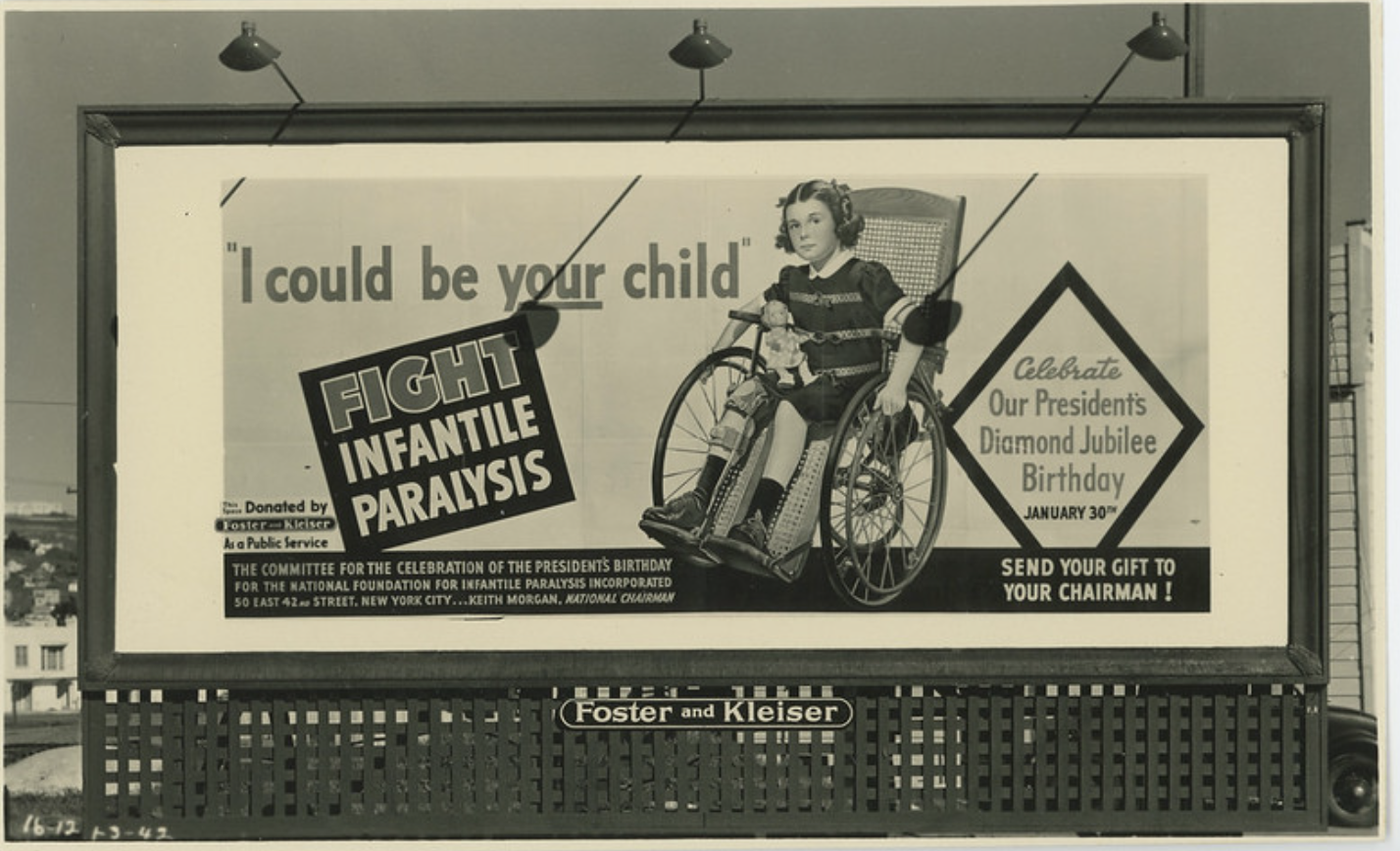

Even before George H. W. Bush signed the Americans With Disabilities Act, past presidents used their lived experiences to ensure protections and resources for people with disabilities. One of our most famous presidents, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, had a disability himself. He did not contract infantile paralysis (more commonly known as polio) as a baby as the name suggests, but was likely exposed to it one summer at Boy Scout camp before spending a summer in New Brunswick with his grandparents. The virus fully manifested in 1921, when FDR fell off a yacht and experienced paralysis throughout his entire body. His was an extremely rare case of adult-onset polio in that he contracted the disease at the age of thirty-nine when most contracted by age four.

Throughout his life, FDR lived with his disability, despite wanting to hide it from the public for fear of looking “weak.” He had custom braces built that allowed him to walk with the help of an aide, which was often his son. FDR’s wheelchair was also made especially for him out of a household dining chair and bicycle wheels – a nimble, lightweight, and highly mobile version of the clunky and awkward wheelchairs of the 1920s.

Although his advisors often wondered how his disability would affect him politically, it did not seem to damage his favorability – he was after all, the only President elected a record four times. The press generally complied with his request that he not be photographed in a “weak” state, i.e., when entering and exiting from his wheelchair, and the Secret Service intervened when necessary. Although disabilities across the board were viewed during this time as weakness, there was no doubting FDR’s strength and resilience. During his lifetime, he founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, the organization we now know as the March of Dimes.

Two decades later, President John F. Kennedy spearheaded the causes of mental and intellectual disabilities, an issue that hit close to home for him. JFK’s younger sister Rosemary was born with an intellectual disability, and her treatment (or lack thereof) was a major impediment to her living a full life close to her friends and family. At the urging of his sister, Eunice Kennedy Shriver (who eventually started the Special Olympics), JFK appointed a panel of scientists and mental health advocates that researched ways to support people with intellectual disabilities, as well as maternal and child health and human development.

Read more about

JFK’s work with people with intellectual disabilities

Source: JFK Library

JFK’s panel made initial recommendations for mental health care that we still follow: refocusing from “custodial” institutions to community-care centers, funding for maternal and prenatal care, funding for teachers of students with intellectual disabilities, and research centers to identify the cause of intellectual disabilities. Subsequent Presidents like LBJ and Gerald Ford acted on many of the panel’s recommendations.

While these Presidential actions certainly made an impact on disability policy, it was the disabled community’s own organizing that led to the largest legislative overhaul of everyday life in the U.S.

FDR navigated his disability using custom braces that allowed him to walk

and a custom wheelchair

(2 minutes 42 seconds) *NO SOUND

Source: NARA YouTube Channel

Accessibility Activism

Both legislators and civilian advocates play integral roles in getting the ADA through Congress and over the finish line. Some of the activism traces its origins far back before the ADA, when activists like Helen Keller, John Beaulieu, and the Blinded Veterans Association began being recognized publicly or invited to the White House.

In the run-up to the vote on the ADA, there were several key figures on the government side. Senator Tom Harkin (Democrat—Iowa) was the author and chief sponsor of ADA in the Senate. When he introduced the bill on the Senate floor, he delivered part of his speech in sign language because he wanted his deaf brother to be able to understand it.

Senator Bob Dole (Republican—Kansas) also advocated for the legislation. While he was serving in Europe in World War II, in 1945, Dole was nearly fatally wounded when he was struck on the upper back and right arm by a German shell. For the rest of his life, he dealt with the consequences of his injuries, which included numbness in his left arm and limited use of his right arm. Representative Patricia Schroeder (Democrat—Colorado) also supported the legislation.

Other supporters included Justin Whitlock, Dart, Jr., an activist who had contracted polio before attending university and who was denied a teaching certificate because of his disability; Patrisha Wright, an activist known as “the General” for her ability to organize the campaign for the ADA; and Shirley Davis, who worked for the Society for Human Resource Management and who contended that people with disabilities possessed valuable abilities that employers needed.

Listen to “Face Off’ AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT (ADA)

6 SEPTEMBER 1989

Source: Kennedy Library

Renewed Independence

Americans With Disabilities Act, 1990

National Archives Identifier: 6037488

The Americans with Disabilities Act was introduced into the House of Representatives and the Senate in 1988 and became law in 1990. Although it was opposed by some businesses and religious organizations because of the costs it would impose on them, in general, the law enjoyed broad public and bipartisan support in Congress.

Bush remarks at signing of the ADA

National Archives Identifier: 594138

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits discrimination against Americans based on a broad range of physical and mental disabilities. ADA excludes certain conditions that might cause illegal activities, such as exhibitionism or pedophilia. This federal civil rights law is similar to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but unlike that law, it also requires employers to provide their employees with what it terms “reasonable accommodations” to enable them to complete their work, and it requires public facilities to be accessible to people with disabilities. This includes public entities such as city, county, state, and federal buildings, public accommodations such as restaurants, bars, and hotels and motels, public housing, and public transportation such as buses and trains.

President Bush comes out in support of the ADA at the Republican National Convention

The law originated in recommendations by the National Council on Disability, which in 1986 drafted the first version of the bill that was introduced to Congress two years later. President George H. W. Bush signed the bill into law on July 26, 1990. An amended version was passed and signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2008 and became law on January 1, 2009.

George W. Bush signs amendments to the ADA in 2009

President George H. W. Bush signed the bill into law in a ceremony on the White House lawn. Before the signing, he noted, “I know there may have been concerns that the ADA may be too vague or too costly, or may lead endlessly to litigation. But I want to reassure you right now that my administration and the United States Congress have carefully crafted this Act. We’ve all been determined to ensure that it gives flexibility, particularly in terms of the timetable of implementation; and we’ve been committed to containing the costs that may be incurred….Let the shameful wall of exclusion finally come tumbling down.”

The Full Picture

One of the activists who sat in his wheelchair beside President George H. W. Bush in the famous photo where he signed the Americans with Disabilities Act into law on the south lawn of the White House was Justin Whitlock Dart, Jr. The scion of a wealthy family from Chicago, Dart was born there on August 30, 1930. He caught polio in 1948, which confined him to a wheelchair for life. He attended the segregated University of Houston, where in 1954, he completed degrees in education and history. However, the university denied him a teaching certificate because he was wheelchair-bound.

President George H. W. Bush Signs the Americans with Disabilities Act (Dart is pictured to Bush’s left)

National Archives Identifier: 6037489

Dart became a successful businessman, but in 1967, he resigned from his businesses and took up the life of an advocate for those with disabilities. He began his advocacy by working on various state and federal disability commissions. When President Ronald Reagan tried to revise the 1973 Rehabilitation Act, Dart opposed it, even though Reagan was a friend of Dart’s family. At their own expense, Dart and his wife Yoshiko went on two “Road to Freedom” tours to all fifty states and several U.S. territories to speak with disabled people about their needs.

Dart was a leading advocate for the Americans with Disabilities Act. After it became law, he served as chairman of the President’s Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities under President Bill Clinton. In 1995, he helped co-found the American Association of People with Disabilities with several other prominent activists.

In recognition of Justin Whitlock Dart’s lifetime of service on behalf of the disabled, President Bill Clinton awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1998. Whitlock died in 2002, of congestive heart failure brought on by post-polio syndrome.

Dogs with Jobs

One major provision of the Americans with Disabilities Act is the codification of rules governing the term “service animal” and where service animals are allowed to go. Under the rules, only dogs that are trained “to do work or perform tasks for a person with a disability” are service animals.

Service animals perform all kinds of tasks, including leading blind people, pulling wheelchairs, reminding people to take their medications, calming people with post-traumatic stress disorder who are about to have or who are having anxiety attacks, and warning people who are deaf of danger or those who are about to have a seizure.

Service animals are permitted to accompany people with disabilities anywhere that members of the public are allowed to go. In hospitals, for instance, they can go into cafeterias, examination rooms, or patient rooms, but not into operating rooms, which are sterile theaters. The handler must always be in control of their service animal.

Interestingly, the ADA also allows miniature horses (twenty-four to thirty-four inches tall and seventy to one hundred pounds) to be certified as service animals if they have been properly trained. Such horses must be housebroken and always under the owner’s control, and the facility must be able to accommodate the horse without compromising its safe operations.

Service dogs are considered medical equipment; if you see one out and about, admire their cuteness from afar, because they’re working! Even though the therapy dogs in the pictures below aren’t service dogs (the ADA does not count therapy dogs or emotional support animals as service animals), we did want to find a way to highlight the important work these good boys (and girls!) do for their humans.