Archives Experience Newsletter - March 28, 2023

A Courtroom Drama

Americans love courtroom drama, as evidenced by the fact that there are 22 seasons of “Law & Order.” But in the 1920s, there were no household TVs to turn on to catch a courthouse verdict. Only certain cases demanded the type of press attention that resulted in the juicy details from arrest to verdict.

One case was the Scopes Monkey Trial. Its name alone probably indicates why it generated so much interest. In fact, the press coverage was so wild that it turned small-town Dayton, Tennessee into, well, a circus.

For modern Americans, the National Archives holds records that allow us to revisit this classic courtroom drama. All rise…

In this issue

He had made quite a name for himself in anti-evolution circles…

A well-known criminal defense lawyer and member of the ACLU and an agnostic…

Two chimpanzees and a “missing link,” a short man with a protruding jaw and a receding forehead…

History Snack

The Case against John Scopes

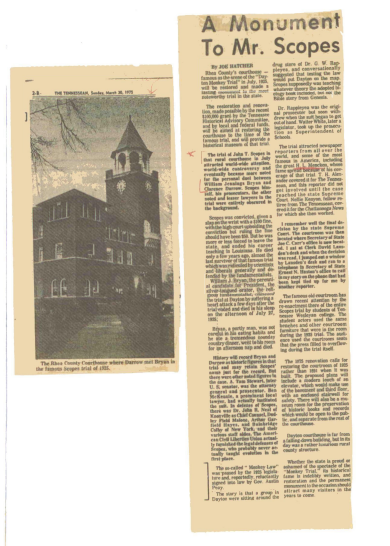

Rhea County Courthouse records (pgs. 54-57)

National Archives Identifier: 135817597

On January 21, 1925, against a backdrop of a bruising national debate about the conflict between religion and the theory of evolution and whether the latter should be taught in public schools, Representative John Washington Butler introduced a bill into the Tennessee legislature that would bar the teaching of “any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.” Exactly two months later, on March 21, Governor Austin Butler signed it into law, thereby instating the first such law in the country.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) immediately saw the law as unconstitutional because “it made the Bible, a religious document, the standard of truth in a public institution.” The organization offered to defend any teacher who was prosecuted for violating the Tennessee law. John Thomas Scopes, a 24-year-old high school football coach who also taught biology in Dayton, Tennessee, agreed to teach evolution in his class so he would be indicted in a test case that the ACLU hoped would go all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court on appeal.

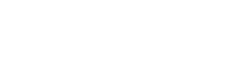

Rhea County Article

John Scopes was arrested and charged on May 7. Town officials in Dayton began preparing for the trial, hoping it would attract positive publicity for their city, which was struggling economically. Anticipating that national media would be covering the trial, they retrofitted the courtroom with radio microphones, telephone and telegraph wiring and movie camera platforms. They built a platform on the courthouse lawn where speakers could address the public and turned six blocks of the main street into a pedestrian mall. The city fathers got their wish—on July 10, the day the trial began, journalists from all over the country flooded into Dayton, along with tourists from out of town and lookers-on from the countryside.

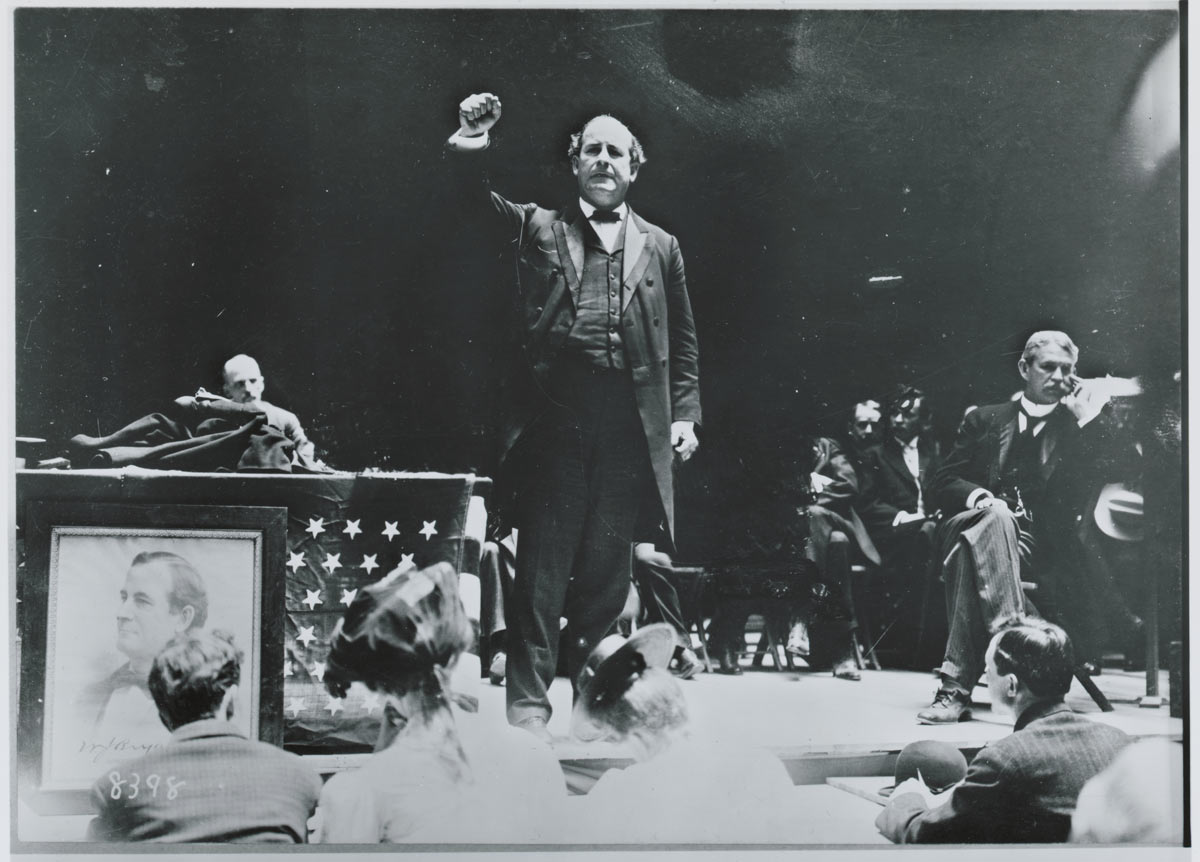

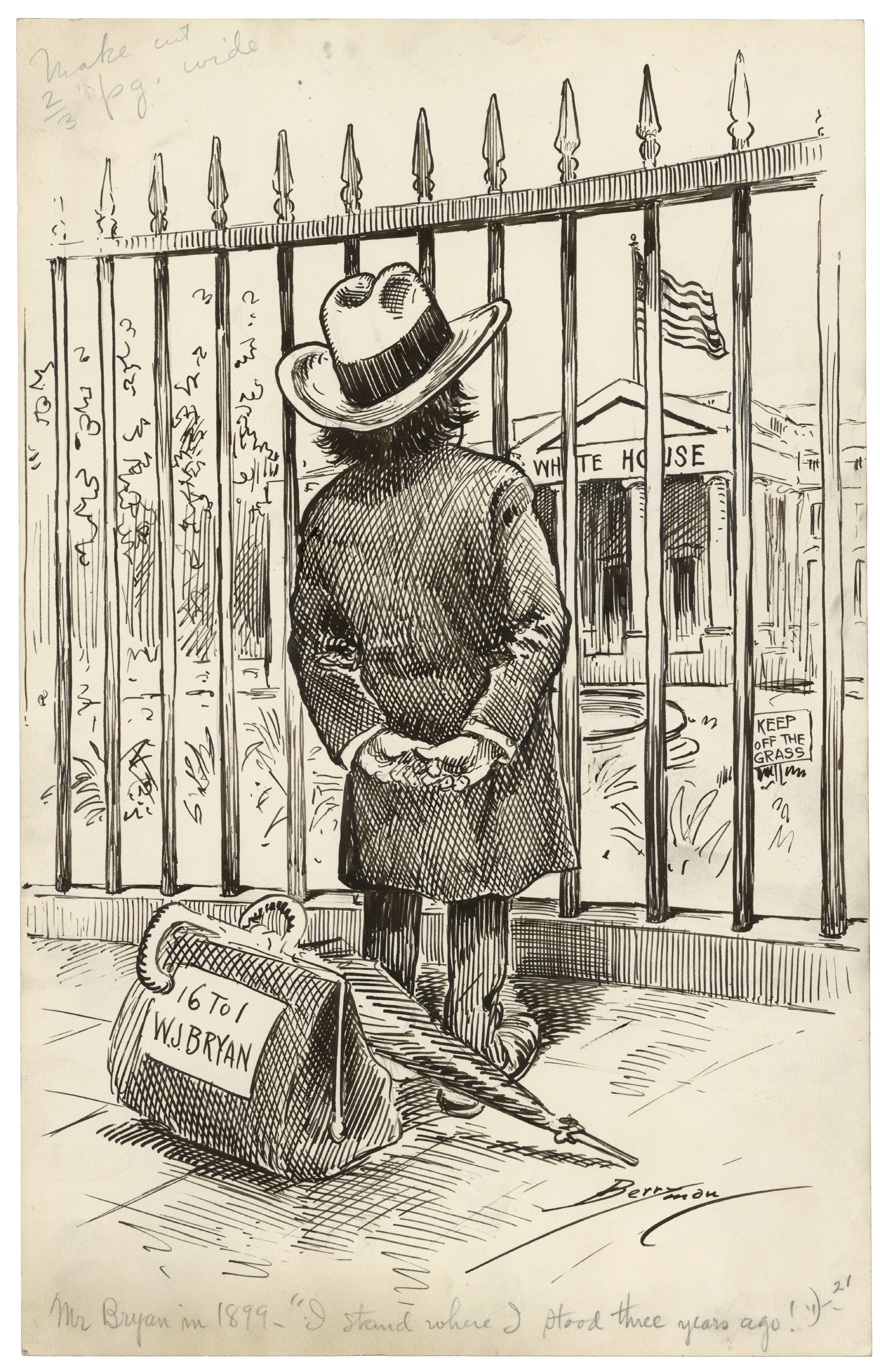

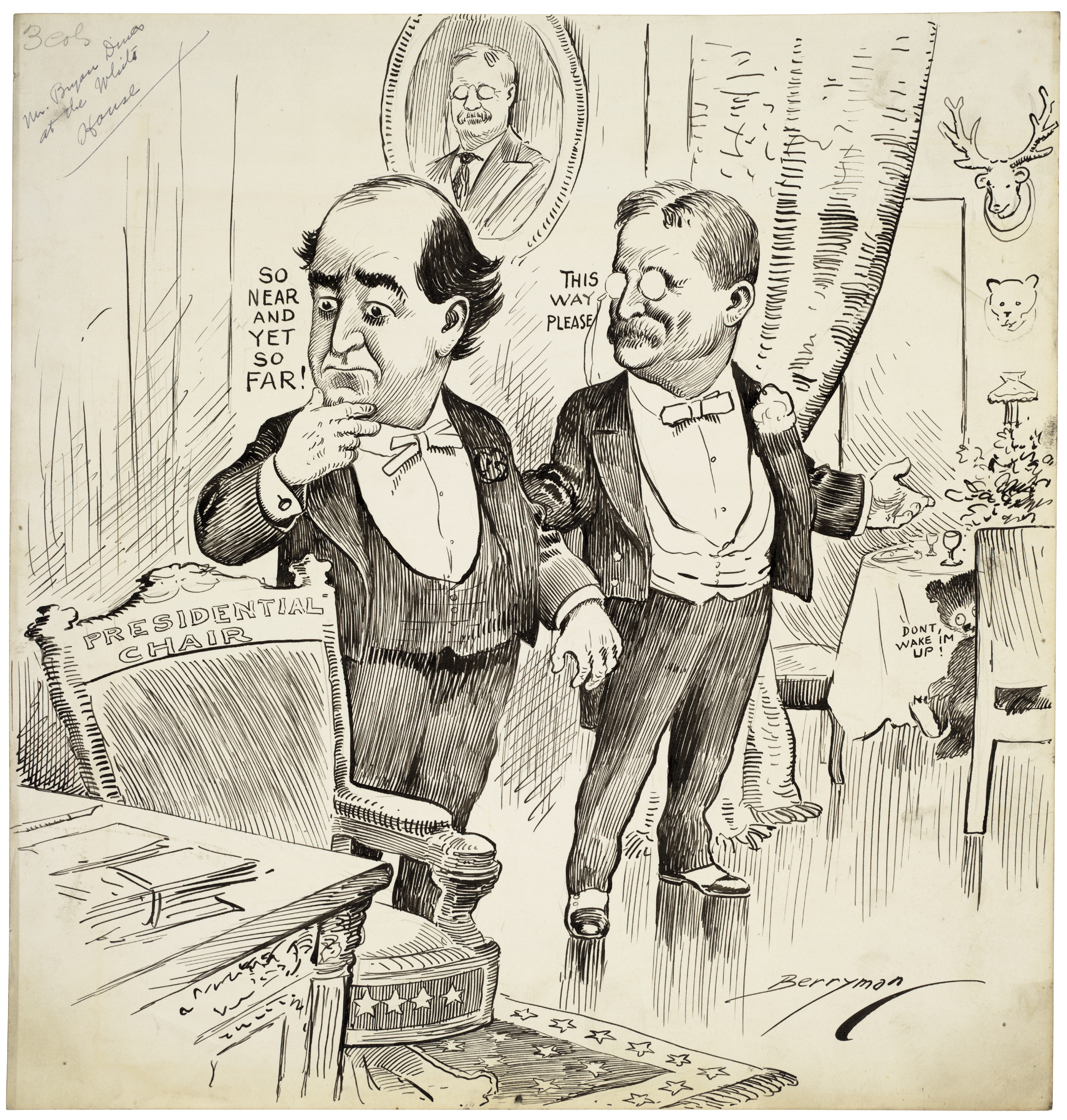

For the Prosecution: William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan, quite possibly the most famous lawyer in the country at that time, agreed to serve as special counsel for the prosecution in the Scopes trial. Bryan had run for president three times on the Democratic ticket, had served as Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wilson and was a lifelong Presbyterian. Beginning in 1921, he had made quite a name for himself in anti-evolution circles, traveling around the country delivering speeches titled “The Menace of Darwinism” and “The Bible and Its Enemies.” The rest of the prosecutorial team included Tom Stewart, the district attorney for the 18th Circuit Court, and attorneys Ben B. McKenzie and Herbert and Sue K. Hicks.

The prosecution’s argument was straightforward: John Scopes had violated the state’s law by teaching his students the theory of evolution.

For the Defense: Clarence Darrow

Clarence Darrow’s childhood home, the “Octagon House”

To counter Bryan, the defense team called upon Clarence Darrow, a well-known criminal defense lawyer and member of the ACLU and an agnostic. He declined at first because he was concerned the trial would turn into a media circus, but he soon realized that would happen with or without him, and he felt an obligation to argue against the Tennessee statute.

Besides Darrow, the defense team included his law partner W. O. Thompson, F. B. McElwee, ACLU general counsel Arthur Garfield Hays, Dudley Field Malone, a lawyer who had worked at the State Department, and biblical authority Charles Francis Potter, a Modernist Unitarian preacher. The defense intended to argue that the Tennessee law was unconstitutional.

The Proceedings

On July 10, 1925, Judge Raulston set the tone for the proceedings by asking the Reverend Lemuel M. Cartright to open the trial with a prayer. Jury selection for The State of Tennessee vs. John Thomas Scopes then got underway.

The actual proceedings began on July 13. In an eloquent speech, Darrow contended that the Tennessee law violated freedom of religion. The next day, he objected to the judge’s practice of beginning each day’s proceeding with a prayer. The judge overruled the objection because he said the prayer made no reference to the issues of the case.

Rhea courthouse significance letter pg. 1

Rhea courthouse significance letter pg. 2

On July 15, the judge overruled Darrow’s motion to have the Butler law declared unconstitutional, effectively derailing the defense’s entire approach to the case. With that, John Scopes entered a not guilty plea, and the two sides gave their opening arguments. The prosecution then questioned the superintendent of schools and two of Scopes’ students, who testified that he had taught evolution in his classes. The defense called Maynard Metcalf, a zoologist, who stated that evolution was an accepted theory in the scientific community.

The next day, the judge ruled that the defense could not call any more scientists to testify because the question was whether Scopes had violated the law, not the validity of the theory of evolution. Many of the journalists then left town because they thought the trial was, for all intents and purposes, over.

Read the entirety of the proceedings in the Rhea County Courthouse National Register Records

National Archives Identifier: 135817597

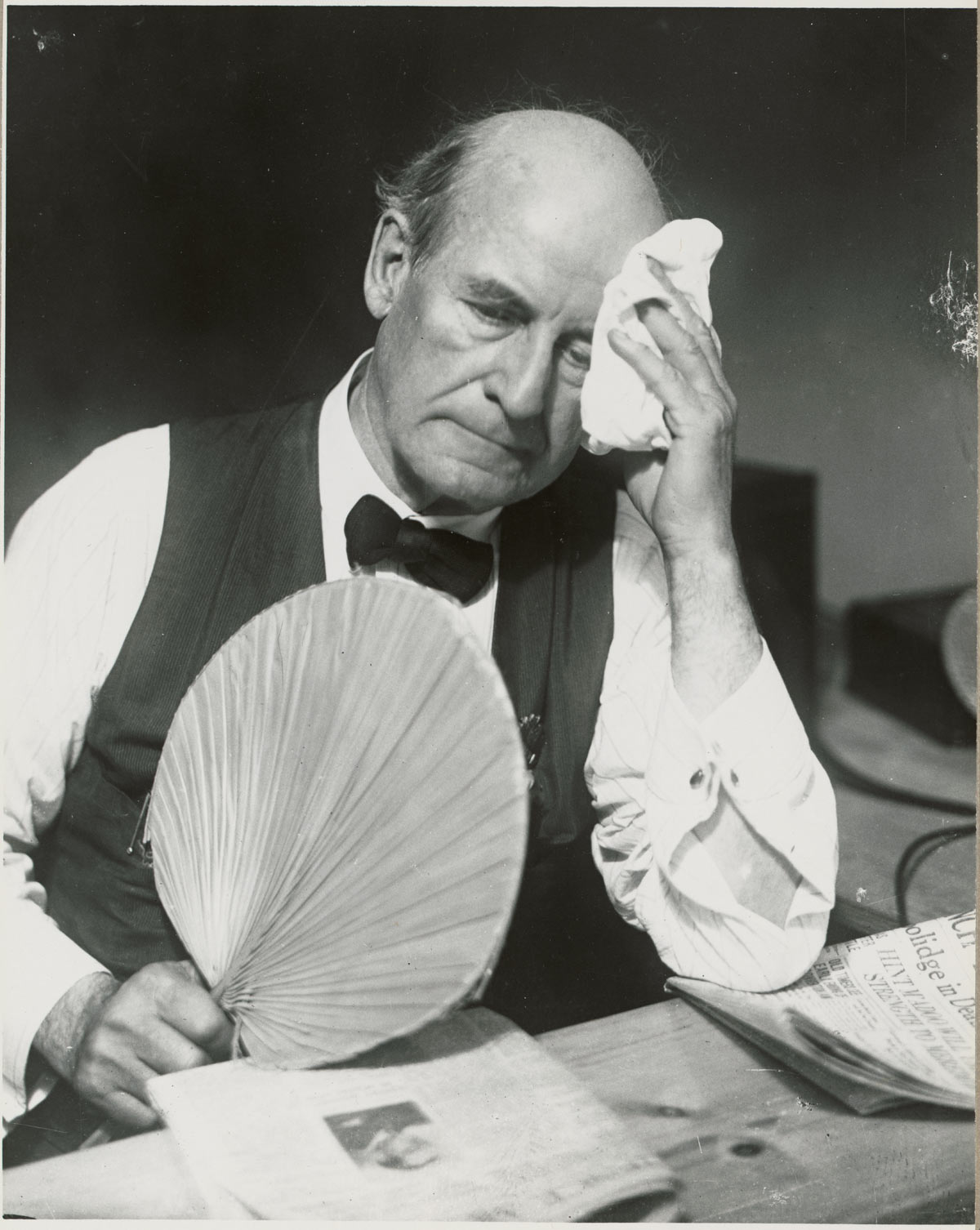

On July 20, Judge Raulston moved the trial outside to the courthouse lawn because of the oppressive heat. Darrow then made his master move—he called Bryan to the stand to testify as a biblical witness. Darrow proceeded to tear apart Bryan’s reasoning that the Bible should be interpreted literally. By all contemporary accounts, the defense attorney publicly humiliated Bryan.

The next day, the judge refused to let Darrow recall Bryan to the stand and instructed the court reporter to strike Bryan’s testimony from the court record on the grounds that it could “shed no light upon any issues that will be pending before the higher courts.”

The Verdict

John Scopes newspaper clipping

Darrow then demanded that the case be sent to the jury and that Scopes be found guilty. This tactic forestalled Bryan’s plan to deliver a final speech to the assembled crowd. The judge obliged Darrow, and the jury returned a guilty verdict in nine minutes. The judge fined Scopes $100, the minimum allowable amount, which equates to just over $1,700 in 2023 dollars. Both the ACLU and Bryan offered to pay the fine on Scopes’ behalf.

John Scopes then issued the only statement he had made at any point in the trial: he intended “to oppose this law in any way I can. Any other action would be in violation of my ideal of academic freedom—that is, to teach the truth as guaranteed in our constitution, of personal and religious freedom.”

Five days after the trial ended, Williams Jennings Bryan died in his sleep in Dayton. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery on July 31, 1925. His tombstone reads, “He Kept the Faith.”

The Circus

H. L. Mencken

Just as Darrow feared, the trial turned into a media circus. Radio WGN broadcast the proceedings live—the first time in history this had occurred in the U.S. Correspondents from more than 100 newspapers and more than 1,000 people crammed into the courtroom before Judge Raulston moved the trial outside.

Preachers set up tents and held revivals on the streets of the town. An exhibit opened in town with two chimpanzees and a “missing link,” a short man with a protruding jaw and a receding forehead. Vendors hawked lemonade, hot dogs, toy monkeys and Bibles.

H. L. Mencken house in Baltimore

H. L. Mencken, a reporter for the Baltimore Sun, covered the trial for that newspaper and brought to bear on Dayton and its townspeople his unrelenting scorn. It was he who labeled the proceedings the “Monkey Trial.” He called Bryan a “buffoon” and the residents of Dayton “yokels” and praised Darrow to the skies.

H. L. Mencken background–significance letter

As had been its intention from the beginning, the ACLU promptly appealed Scopes’ conviction to the Tennessee Supreme Court. In 1927, the court ruled the law was constitutional, but it overturned Scopes’ conviction on a technicality. The result was that the case could not be further appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. It was not until 1968 that a similar case reached the highest court in the land, where it was ruled unconstitutional on the grounds that it violated the First Amendment.