Unexpected Sunshine

The National Archives is the great frontier of sunshine. Across the federal government, the Archives is the leader in providing access to millions of records every day that document the decisions and proceedings of the executive branch. From running the National Declassification Center to hosting Sunshine Week every year, the Archives is where the media and citizens go to learn about our country’s past.

But some documents, photographs, technology patents, and intelligence records are classified for up to 75 years (basically, they are not meant for the general public to ogle), so they are left to be studied by historians. Not all these secret documents remain hidden under lock and key. Some are revealed (by accident or intentionally) long before they are “supposed to be” and consequently create an uproar, but this has always been a part of American history. Leaked documents and technology have precipitated global conflict, shaped our perceptions of government, and even helped in founding a new nation.

More interesting than the specifics of a leak is the story behind it. This week’s newsletter reminds us of documents and technologies that have made unplanned entrances into the public realm and the stories behind them.

Mum’s the word.

🤫

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Two Can’t Keep a Secret

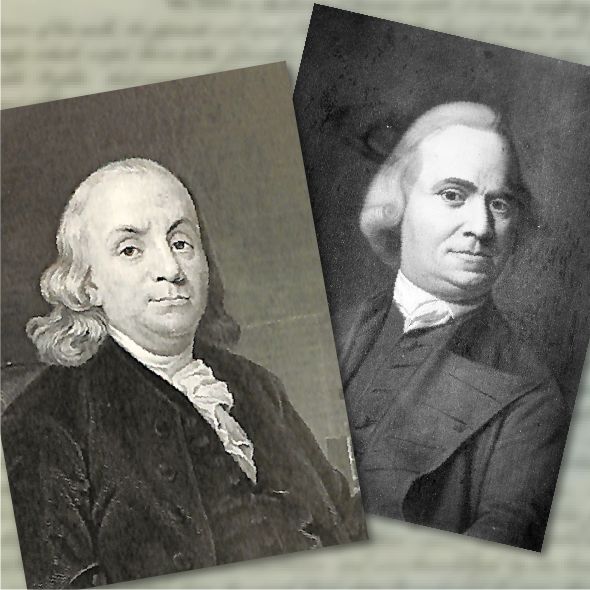

In June 1773, the Boston Gazette published a series of letters that Massachusetts province Governor Thomas Hutchinson and Lieutenant Governor Andrew Oliver had written to Thomas Whatley, an assistant to George Grenville, the British prime minister. The letters concerned the Townshend Acts, which empowered the British government to tax the colonists on imported goods, and furthermore asserted its authority to tax them without colonial representation in Parliament.

In one letter, Hutchinson commented that it would be impossible to grant the colonists all the rights they would have possessed if they were living in England. Oliver recommended changing the governor’s council, which until then was comprised of individuals appointed by the governor, to one with members who would be appointed by the crown.

When the Boston Gazette published the letters, many colonists who opposed Hutchinson’s rule were incensed. In Boston, Hutchinson and Oliver were burned in effigy on Boston Common. The Massachusetts governor’s council and assembly petitioned Britain to remove Hutchinson from his post.

But in England, the big question was how the letters had fallen into the hands of the colonists in the first place. Speculation first lighted on John Temple, a colonial official who had written to Thomas Whatley in their respective professional capacities. After Thomas Whatley’s death, Temple asked his brother, William Whatley, for permission to retrieve the letters he had written to Thomas, and William agreed. After the letters were published, William Whatley accused Temple of stealing them, a charge that Temple adamantly denied. Their exchanges became so heated that William Whatley and John Temple fought a duel over them. Whatley was injured in the duel, but the two then planned to face one another again after Whatley had recovered.

At that point, Benjamin Franklin, who was in London advocating on behalf of Massachusetts, issued a statement saying he had been in receipt of a packet of letters written to Thomas Whatley. Franklin had sent them to the colonies, where they had come into the possession of Samuel Adams. Franklin had very clearly stated that nothing from the letters should be made public, but Adams nevertheless let certain officials know about the letters and their contents.

Publication of the letters certainly threw gasoline on the fire of the colonists’ grievances, but their most important effect was quite possibly on Benjamin Franklin himself. In 1774, British Solicitor General Alexander Wedderburn publicly reprimanded Franklin for his role in the affair in the Privy Council, accusing him of sedition. The meeting had been called to discuss Hutchinson’s fate, but it was Franklin who lost his job—the council fired him from his position of postmaster general. Sheila Skemp, the author of The Making of a Patriot: Benjamin Franklin at the Cockpit, contends that up until that time, Franklin had been loyal to Britain, but the experience was one of his first steps toward becoming a revolutionary on behalf of the colonies.

Starting the Rumor Mill

Disturnell, Nueva York, 1847

The signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo formally ended the Mexican-American War, which was fought between 1846 and 1848 and resulted in Mexico ceding more than half of its territory to the United States. The land that the U.S. received encompasses parts of what is now Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. Mexico also relinquished all its claims to Texas and agreed that the Rio Grande was the border between the two countries.

National Archives Identifier: 299809

While U.S. senators were still discussing the finer points of the treaty, New York Herald reporter John Nugent published a leaked copy of the treaty. Despite virulent questioning by the furious senators, Nugent refused to say who had given it to him. Definitive proof of who that person was is still lacking, but a decade later, President James Buchanan handed Nugent a plum assignment, sending him to investigate events in New Caledonia (now British Columbia, Canada). Some historians think Buchanan, who was secretary of state under President James Polk, had leaked the treaty to Nugent and then given him that commission as a reward for his silence.

In the Papers

In 1967, when the Vietnam War was at a critical point, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara commissioned the “Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force,” commonly known as the Pentagon Papers. The report revealed that the Johnson Administration had been lying to the public and to Congress about the U.S. military’s true situation in Southeast Asia, as well as about the scope of the conflict.

In June 1971, Daniel Ellsberg, who had worked on the report, leaked it to the New York Times, which published it on the front page of the paper. Publication sparked widespread and immediate controversy and protests across the country.

President Richard Nixon at first was not inclined to do anything to suppress the publication because he thought it reflected badly on the previous two administrations, not his own. But Henry Kissinger told Nixon that Ellsberg and his friend, Anthony Russo, who had helped him photocopy the report, were guilty of espionage and that if they were not prosecuted, it would be harder to hold people who leaked government secrets accountable.

Nixon and Attorney General John Mitchell tried to persuade the New York Times to stop publishing the papers. When that didn’t work, they got an injunction to force the newspaper to stop publication on June 14. Four days later, the Washington Post began publishing the report. Meanwhile, the New York Times appealed the injunction.

The case was argued before the Supreme Court, while simultaneously, more news organizations across the country began publishing the report. On June 30, 1971, the Supreme Court ruled 6–3 that the injunction could not stand. Daniel Ellsberg was charged with stealing secret documents. However, when it came to light that the government had set out to discredit Ellsberg via illegal actions, including burglarizing Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office in Los Angeles and wiretapping Ellsberg’s phone, all charges against him were dropped.

The revelation that government operatives were illegally monitoring American citizens such as Ellsberg and the Democratic National Committee led to investigations that also uncovered the Watergate scandal, which eventually toppled the Nixon administration.

In cooperation with the John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard M. Nixon Presidential Libraries, the National Archives released the unredacted version of the entire Pentagon Paper on the fortieth anniversary of their being leaked to the press.

History Snacks

Cryptic Content

Joseph Rochefort

What could be more fun than sending someone a message that looks innocent, but that actually contains super-secret information? Cryptology, or writing in code, has been practiced by governments and individuals for centuries.

After 200 years, a glimpse into The Art of Secret Writing

Source: NARA’s The Text Message blog

Midway – The Battle That Changed the War in the Pacific

Source: Roosevelt Library’s Forward with Roosevelt blog

Secrets are secrets, but some secrets are more important than others. In 1942, when the United States was still reeling from the attack on Pearl Harbor and the war in the Pacific was going badly, American cryptologist and naval officer Joseph John Rochefort and his team, in collaboration with British and Dutch cryptologists, succeeded in breaking the code that the Japanese encrypted their messages and thus set into motion the U.S.’ successful victory at the Battle of Midway.

In 2011, the National Security Agency declassified more than 50,000 pages of information about cryptology and other clandestine activities. The National Archives is the repository of these documents.

U2 Could Get Caught

Leaked documents can cause governments embarrassment and sometimes even consternation, but technology can also be leaked and might sometimes be more damaging. A case in point is the U-2 spy plane incident, which occurred on May 1, 1960, when an American spy plane piloted by Francis Gary Powers was shot down over the Soviet Union. Representatives of the U.S. and other western countries were just about to sit down at the negotiating table with the Russians, but when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev learned of the incident, he delivered a furious speech and walked out of the summit.

U-2 Spy Plane Incident

Eisenhower Library Online Documents

Recovered Items from American U2 Spy Plane

National Archives Identifier: 72736152

The Russians recovered the wreckage of the airplane and went through it thoroughly. They took full advantage of the situation, trying Powers for espionage and sentencing him to ten years in prison. They also created exhibitions, like the one shown above, of materials they had recovered from the U-2 spy plane.

After serving two years in jail, Powers was released in a prisoner swap and returned to the U.S. He was a controversial figure because many believed the persistent but false myth that U-2 pilots were instructed to take a cyanide capsule to avoid capture. Powers affirmed this, contending that his handlers at the CIA had never given him these instructions. Gary Powers continued to live and work in the United States until his death in a traffic helicopter accident in 1977. In 2000, Powers’s family was presented posthumously with the Prisoner of War Medal, Distinguished Flying Cross, and National Defense Service Medal. Then-CIA Director George Tenet also authorized Powers to receive the Director’s Medal for extreme fidelity and extraordinary courage in the line of duty.