Uncle Sam’s Library

War has always been devastating, but in the 20th century, the introduction of machine guns and chemical warfare took the destruction to another level. With Europe in the grips of a power struggle, the United States entered World War I in 1917, sending our soldiers into a grim conflict of trench warfare, mustard gas, and high casualties.

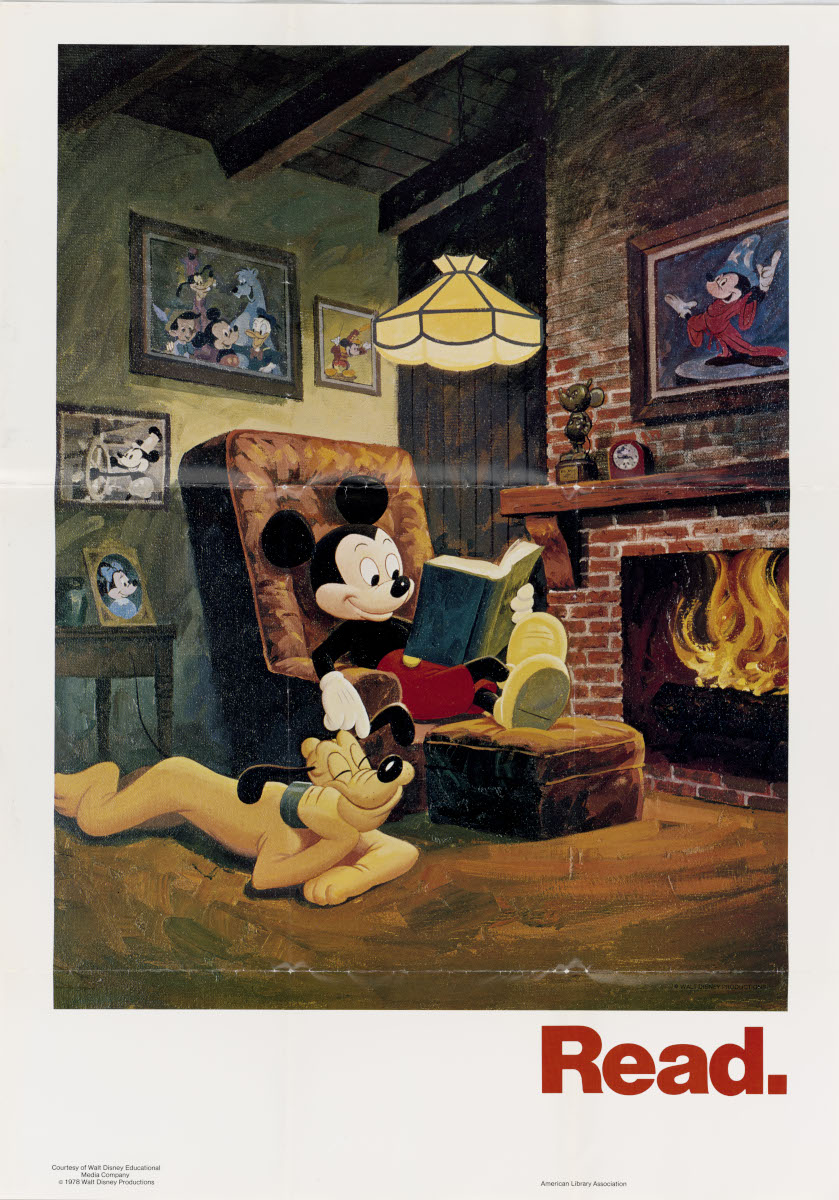

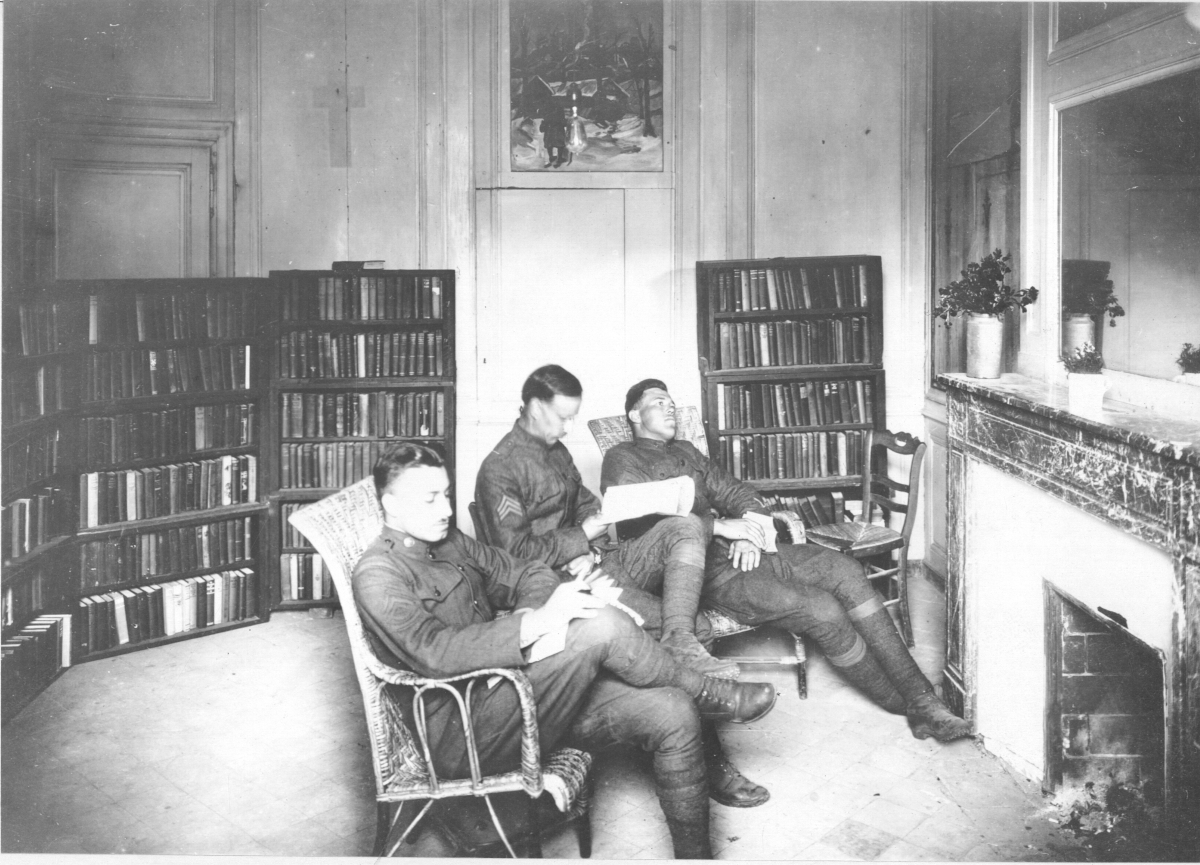

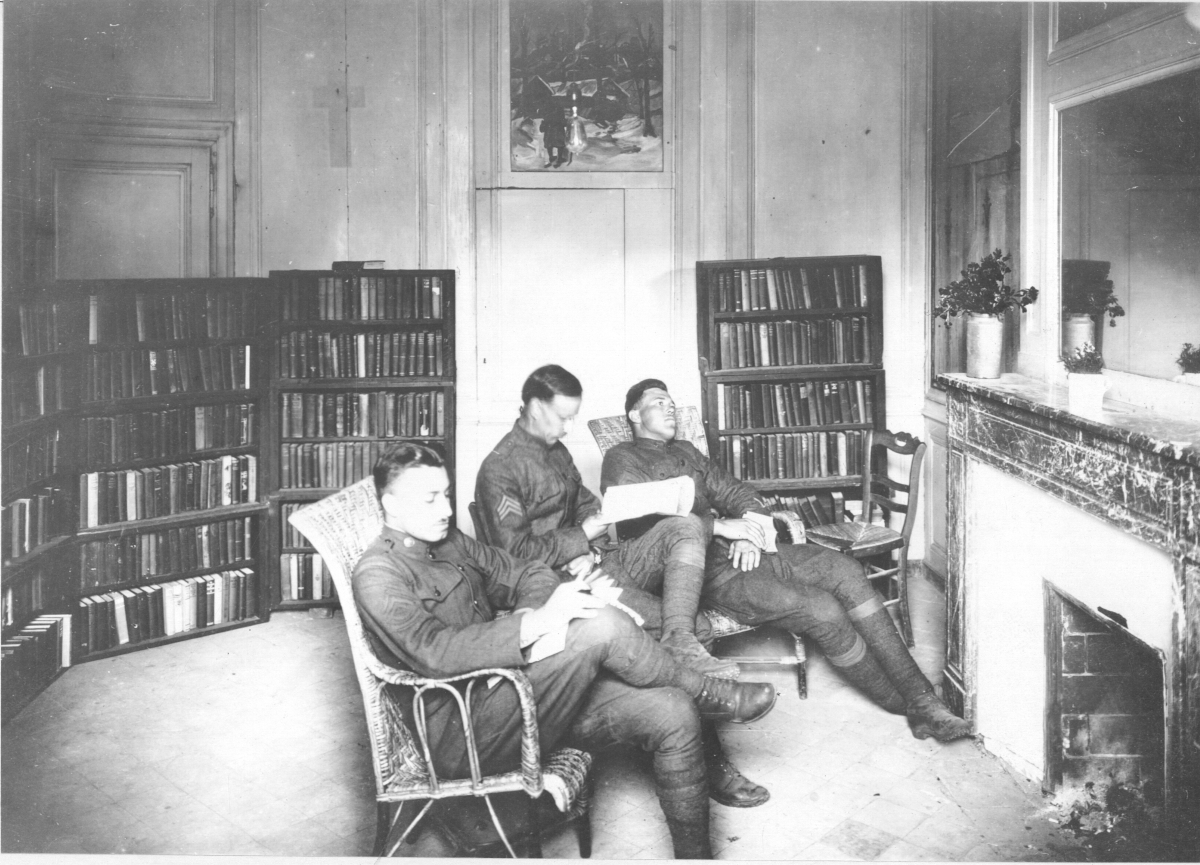

But the American Library Association provided a temporary reprieve for these soldiers. The reading materials that were given to them became a lifeline, a means to escape the horrors of war, even if it was just via paper.

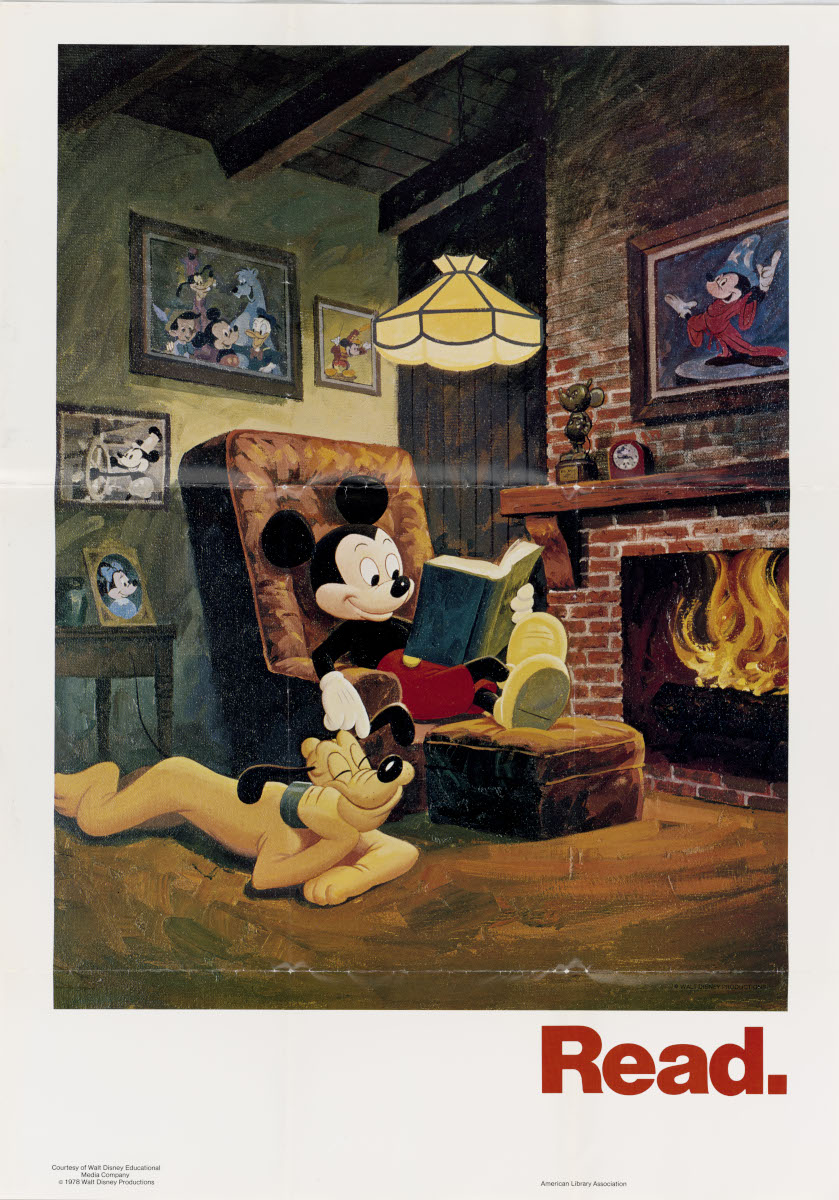

Tomorrow is National Book Lovers’ Day! What better way to spend it than reading?…

In this issue

History Snack

Book Lovers Unite!

On October 6, 1876, when the United States had just celebrated its 100th birthday by throwing itself a huge party, the Centennial International Exposition in Philadelphia, 103 librarians, including 90 men and 13 women, met at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. As the meeting ended, they passed a register around and invited anyone who wanted to become a charter member of an organization aiming “to enable librarians to do their present work more easily and at less expense” to sign up.

Thus was born the American Library Association. From its beginnings, it has been an organization devoted to firsts: the first to host a children’s story hour and to gather a children’s collection, initiated by librarian Caroline Hewins at the Hartford, Connecticut, Young Men’s Institute in 1882; the first to create a children’s reading room at the public library in Brookline, Massachusetts; the first to send out a bookmobile from the Washington County, Maryland, Public Library. The ALA also elected a woman, Theresa West Elmedorf, as its president in 1911, nearly two decades before women won the right to vote in the United States.

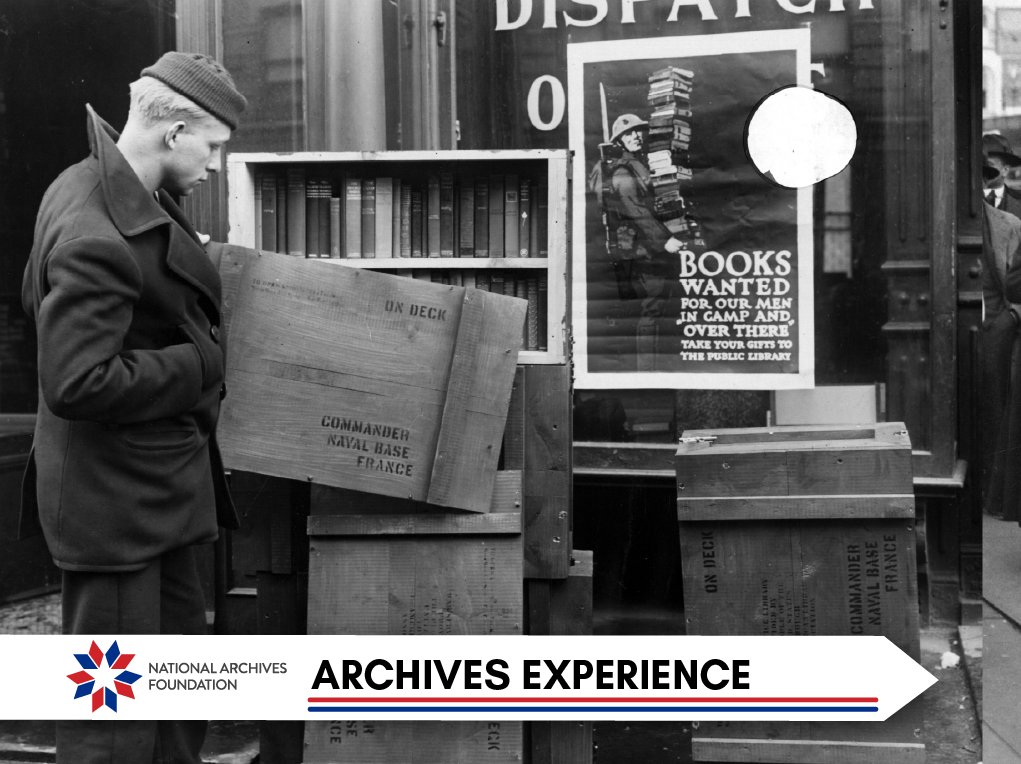

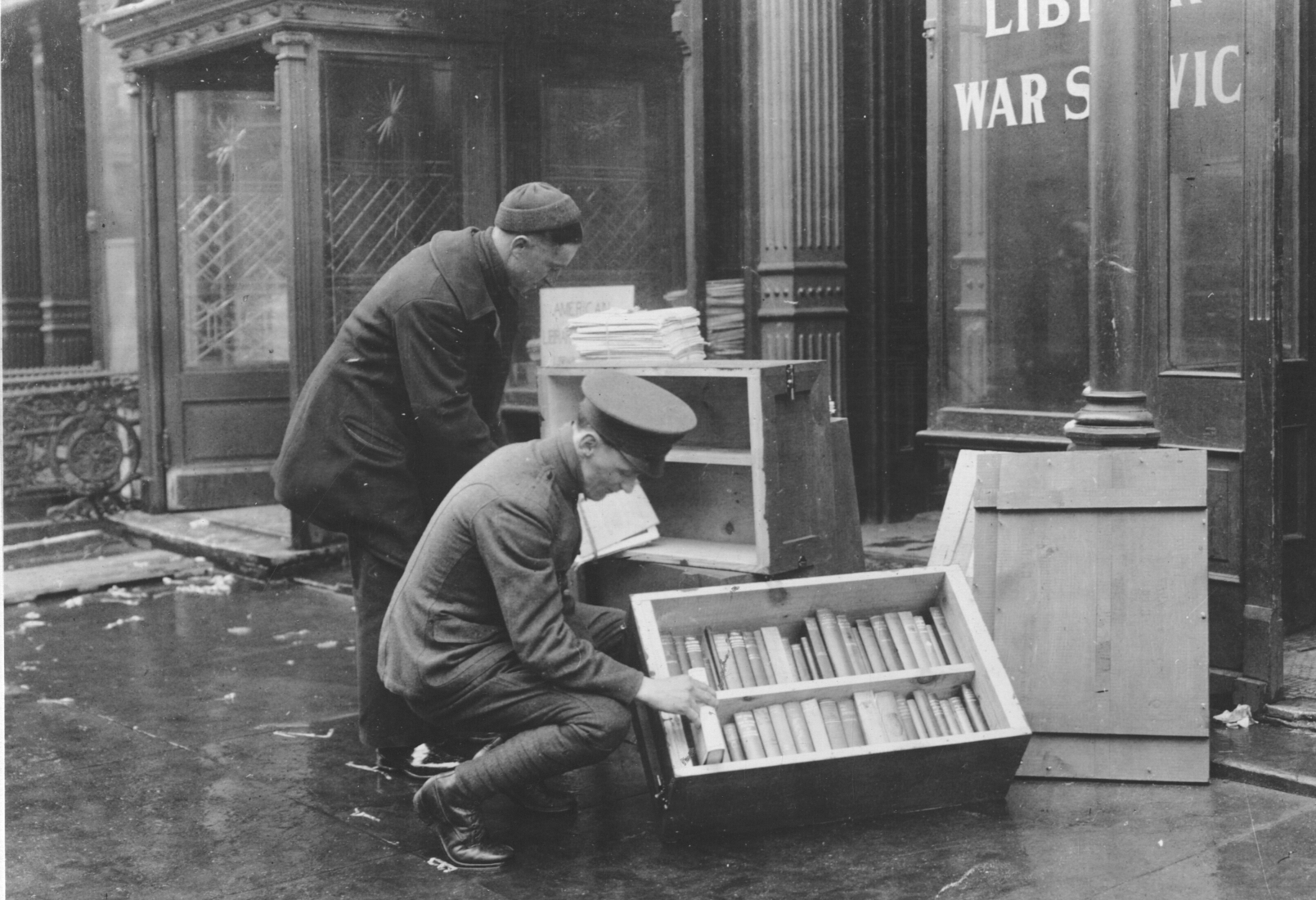

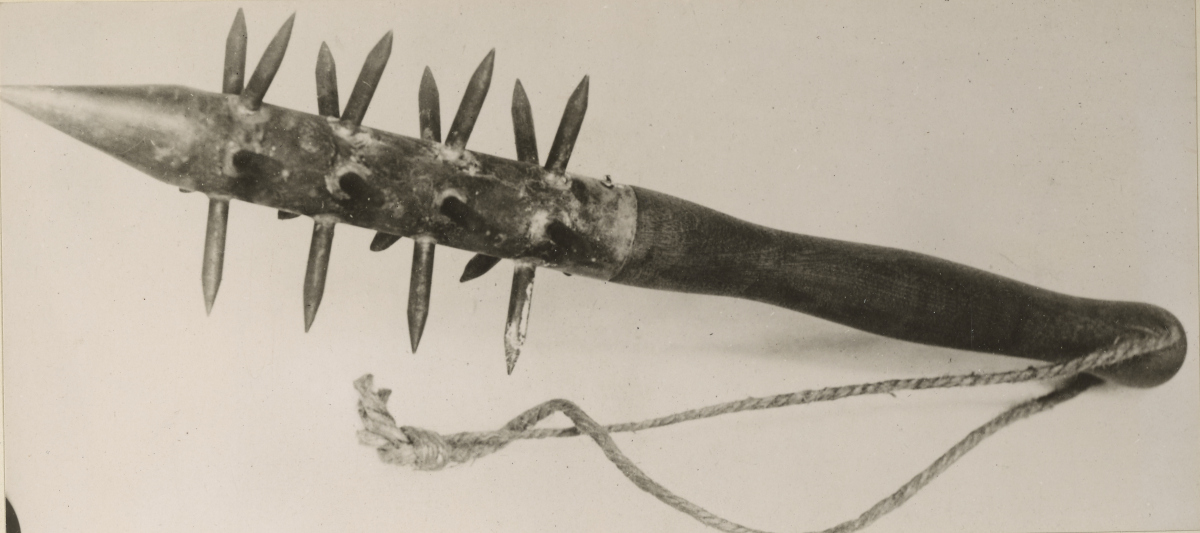

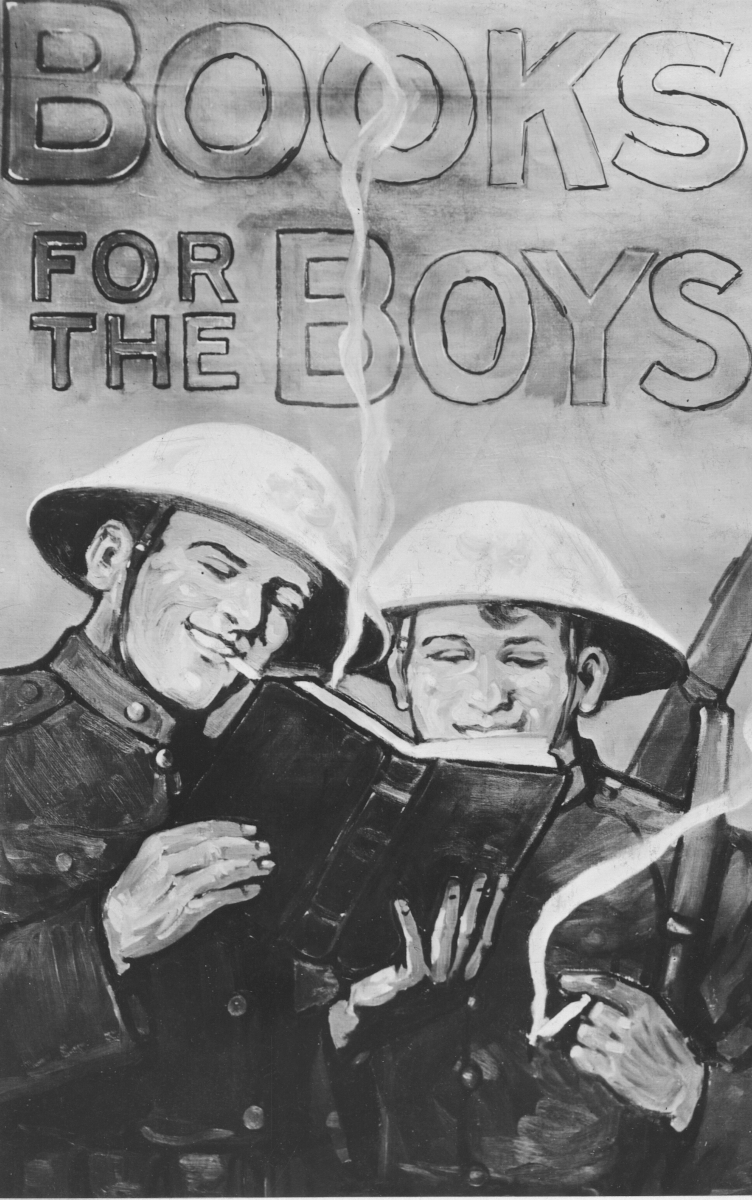

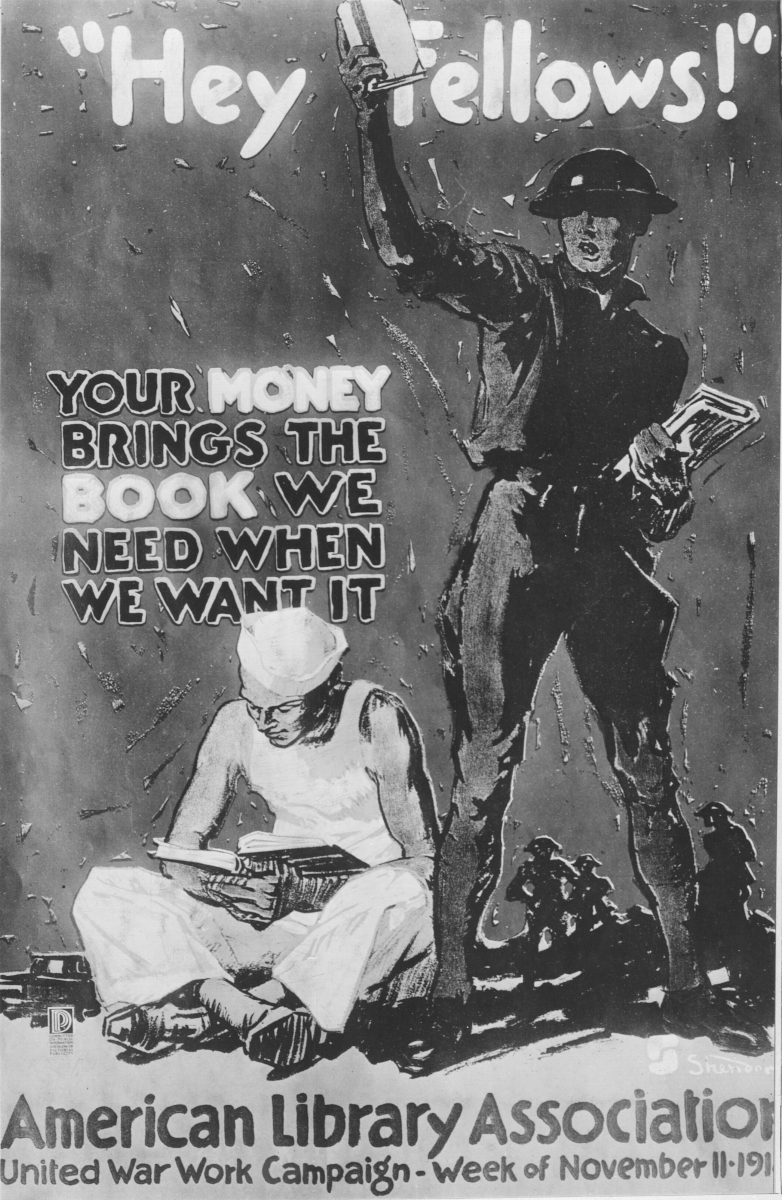

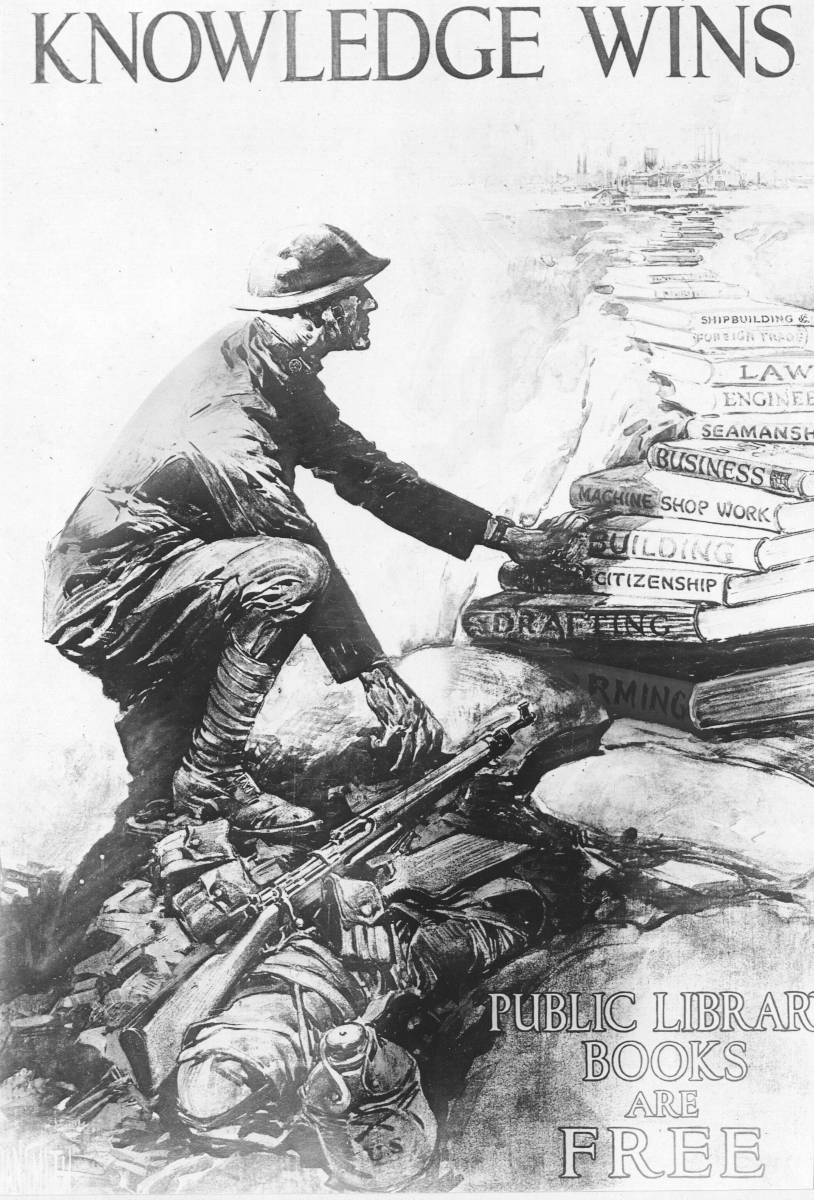

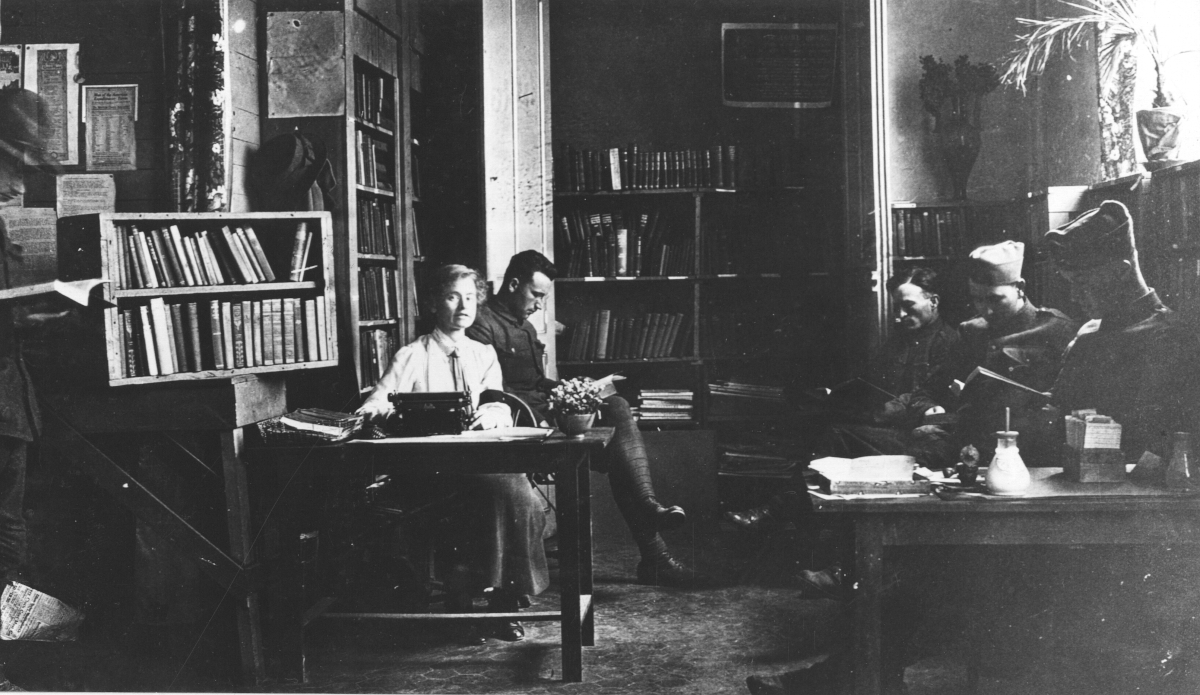

In 1917, as the United States entered World War I, the Executive Board of the ALA created a Committee on Mobilization and War Service Plans with the mission to provide books and periodicals to military personnel at home and abroad. Having raised an initial $1 million, the committee set about getting reading materials into the hands of American soldiers, wherever they might be.

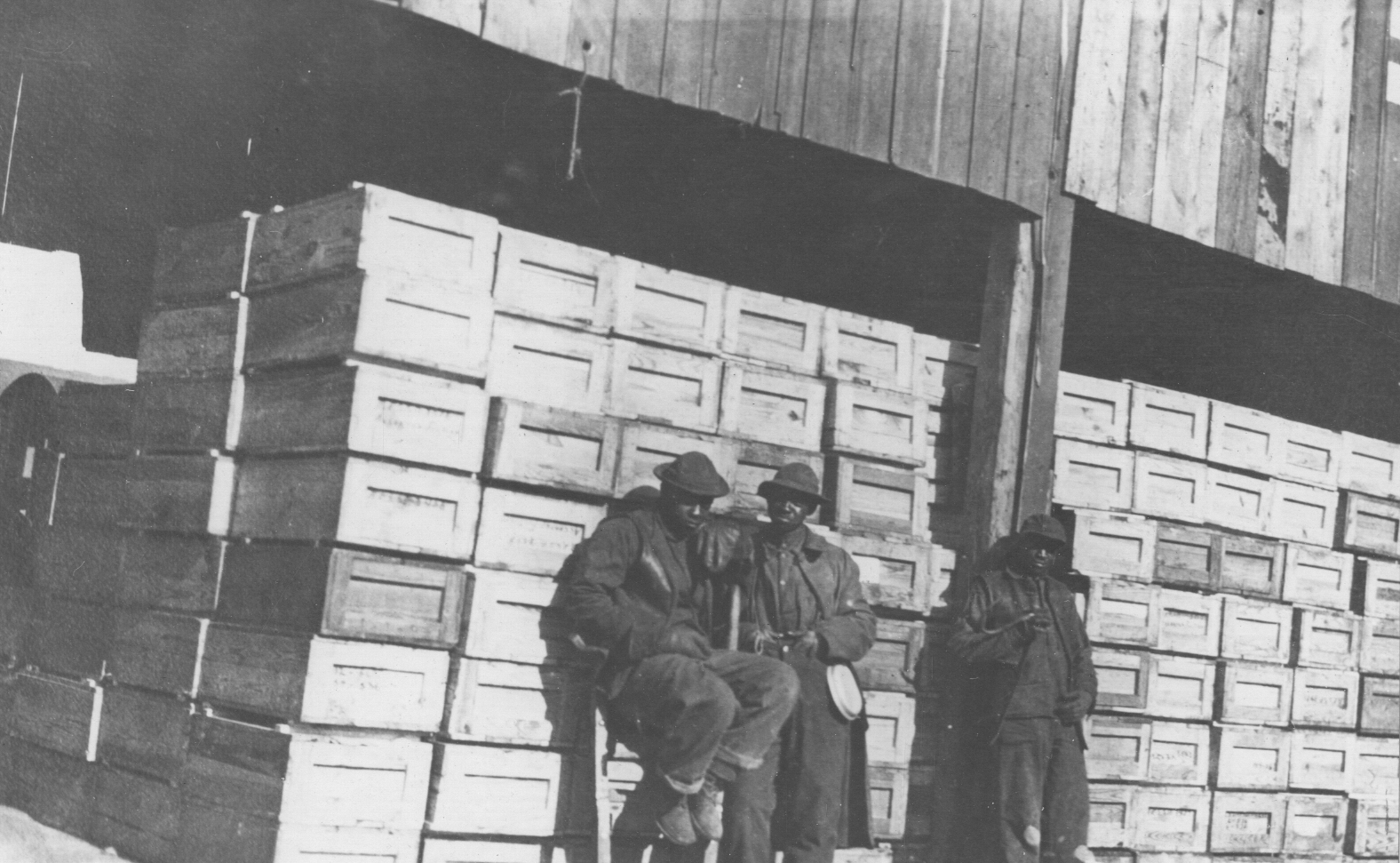

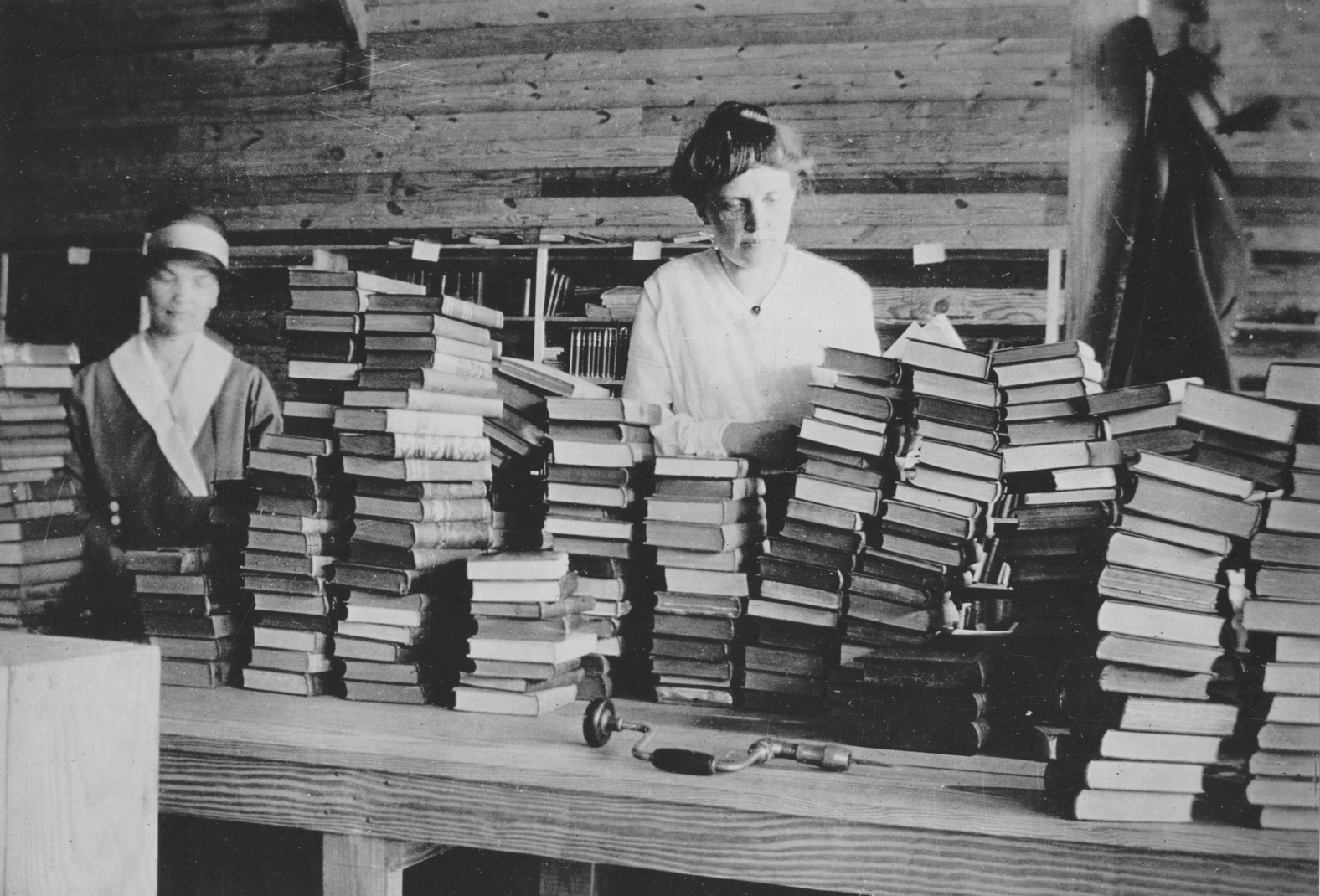

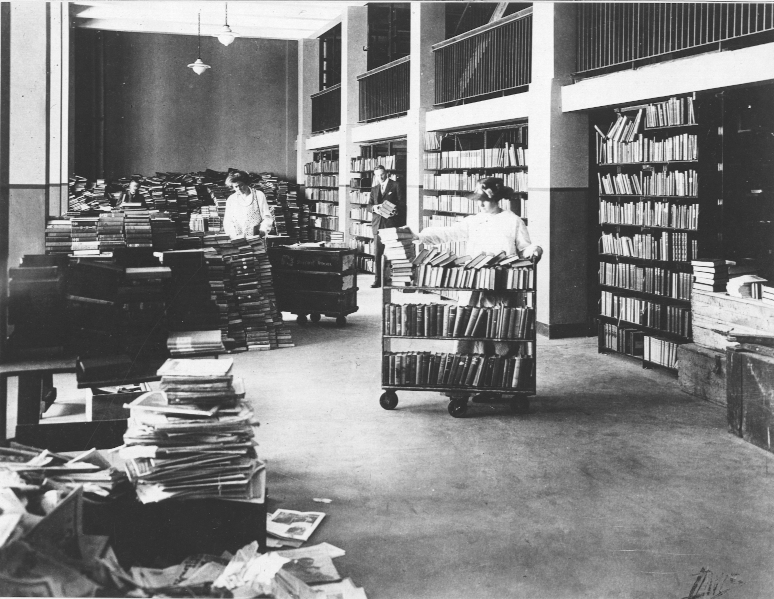

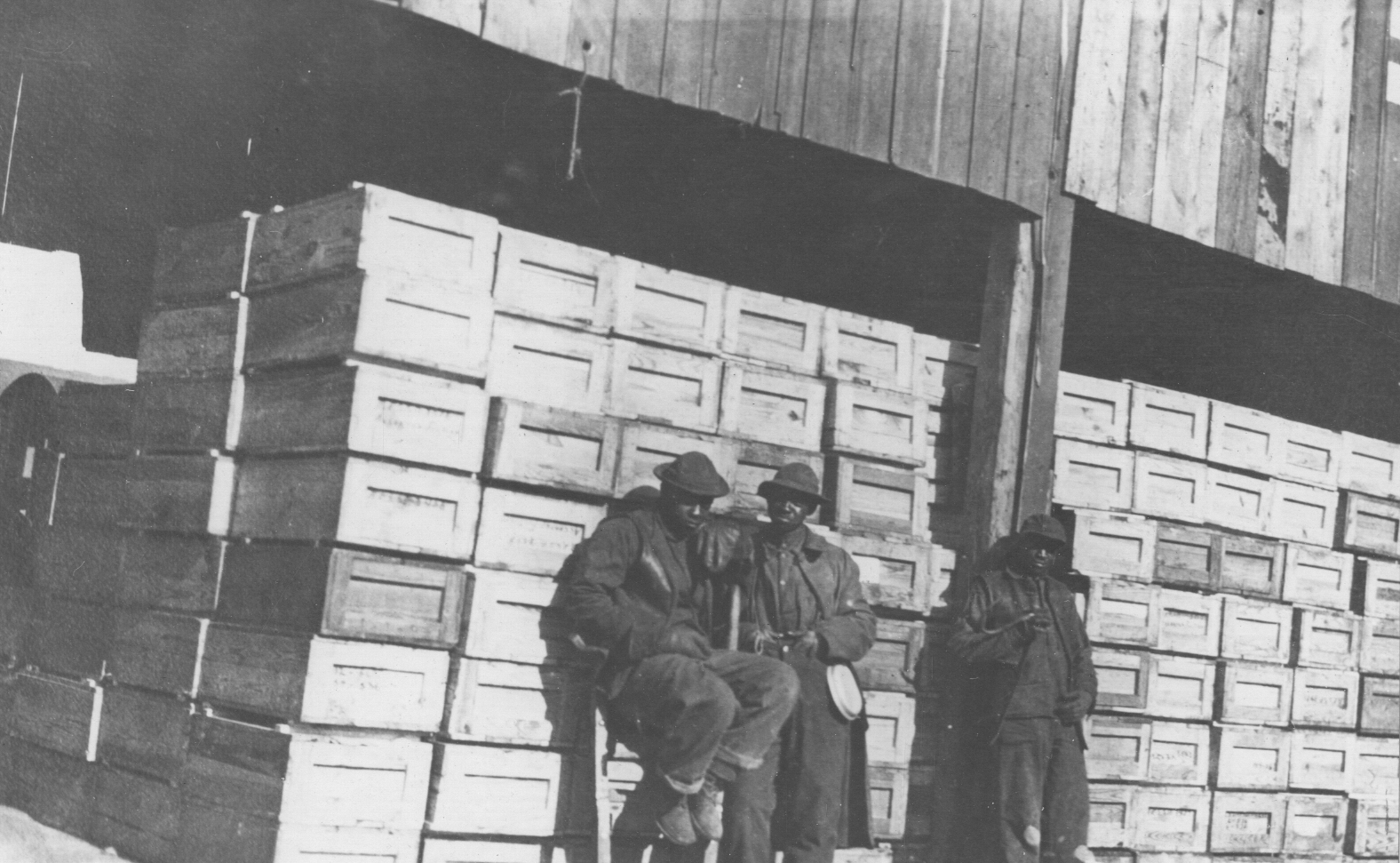

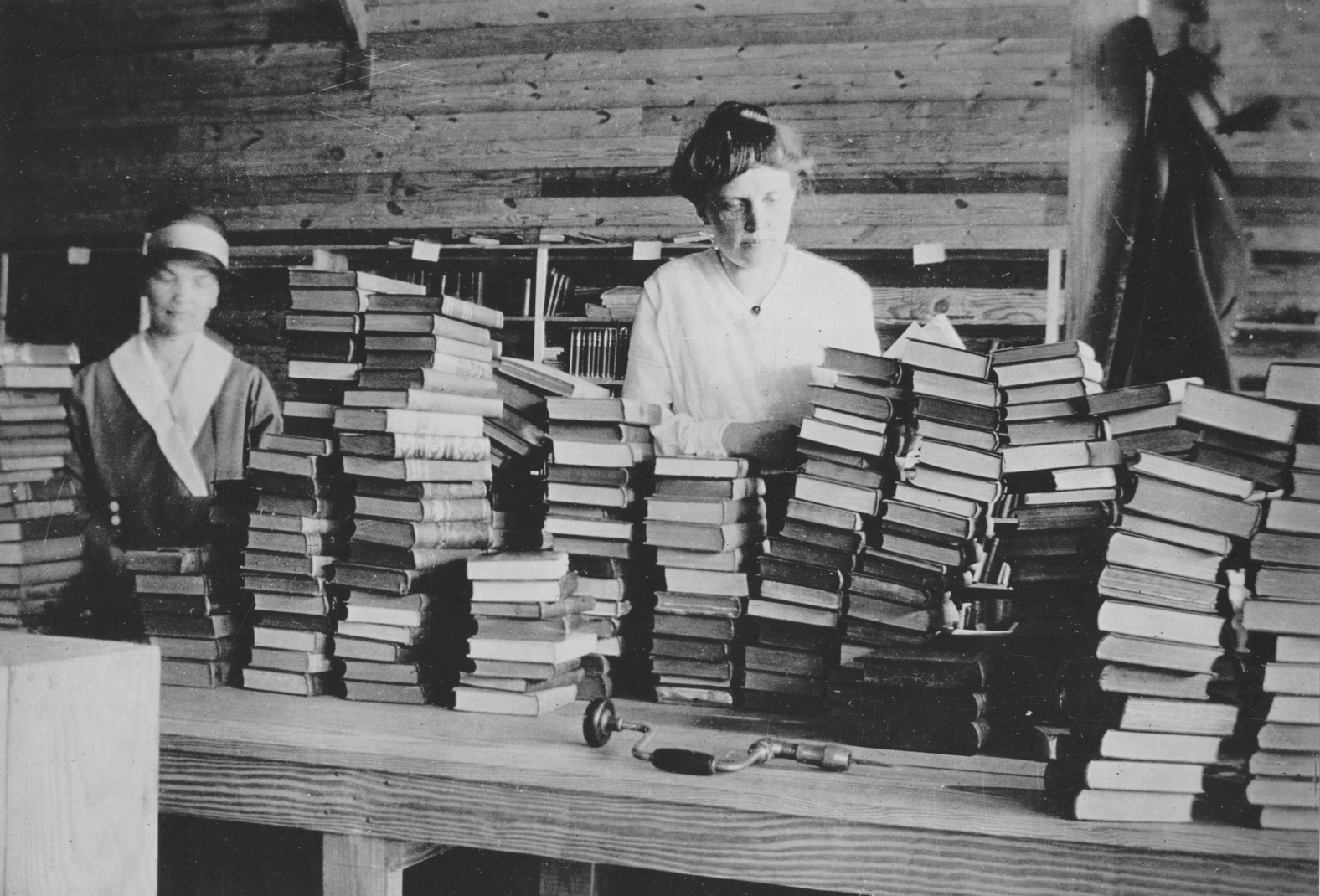

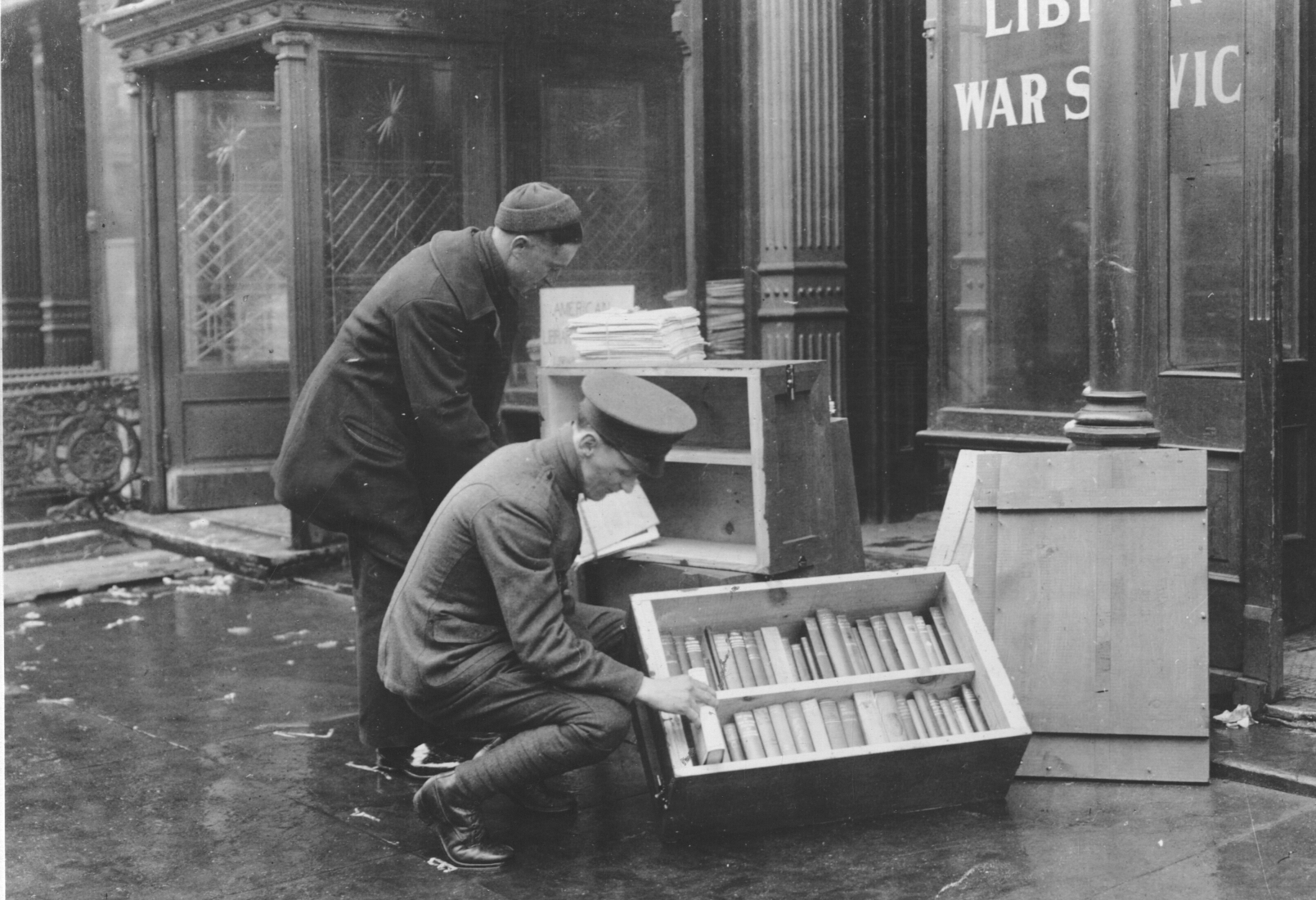

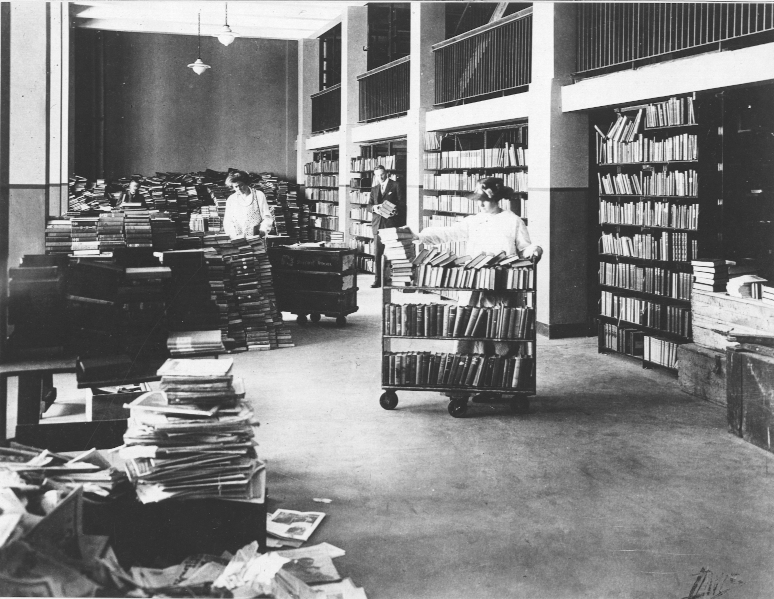

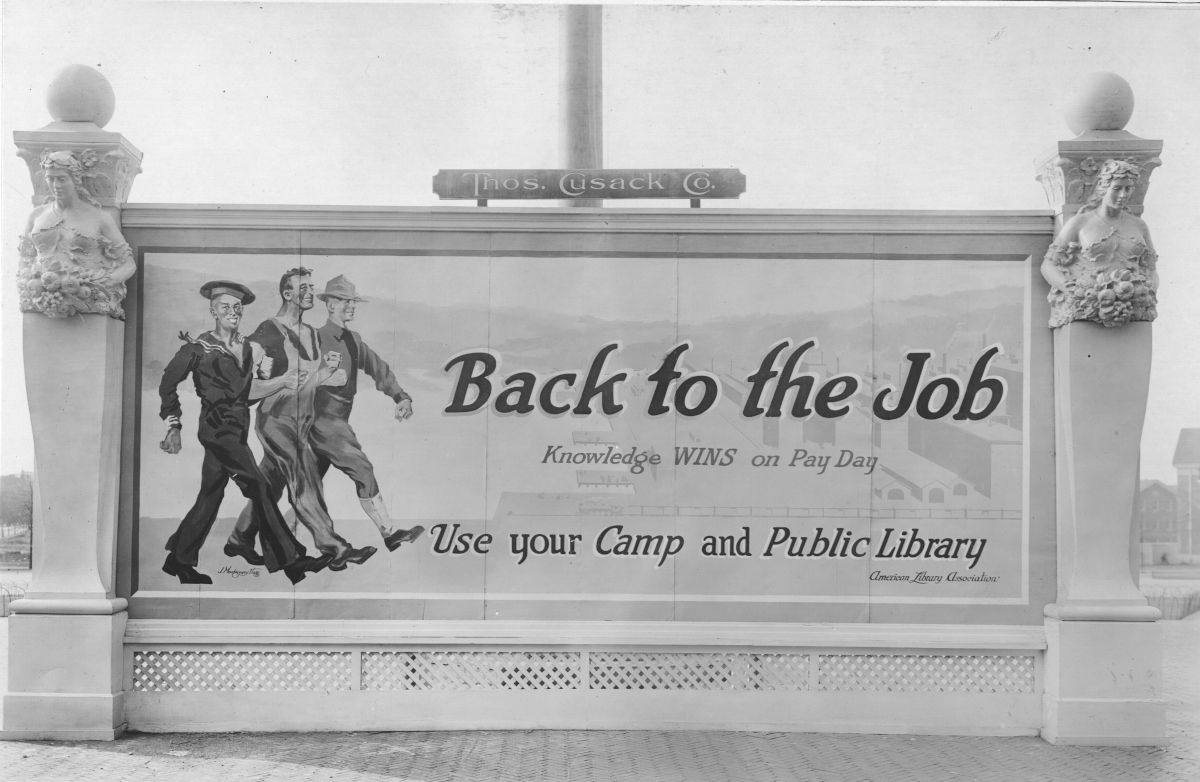

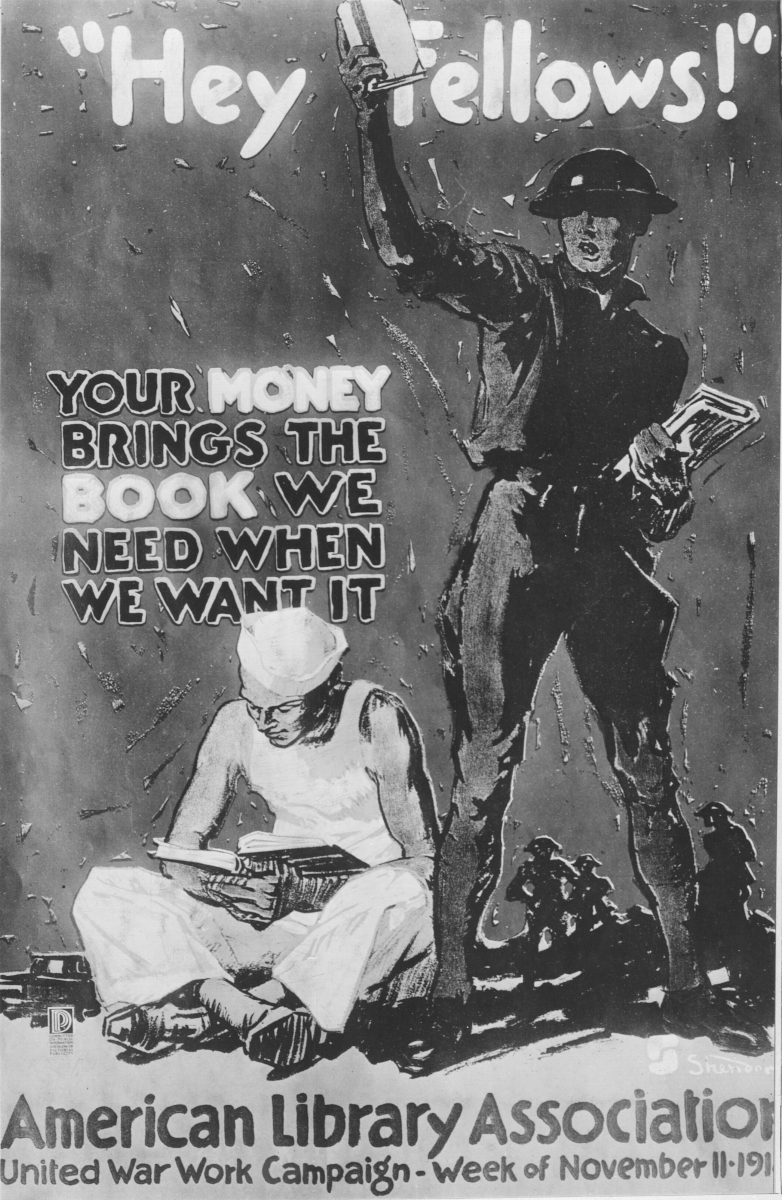

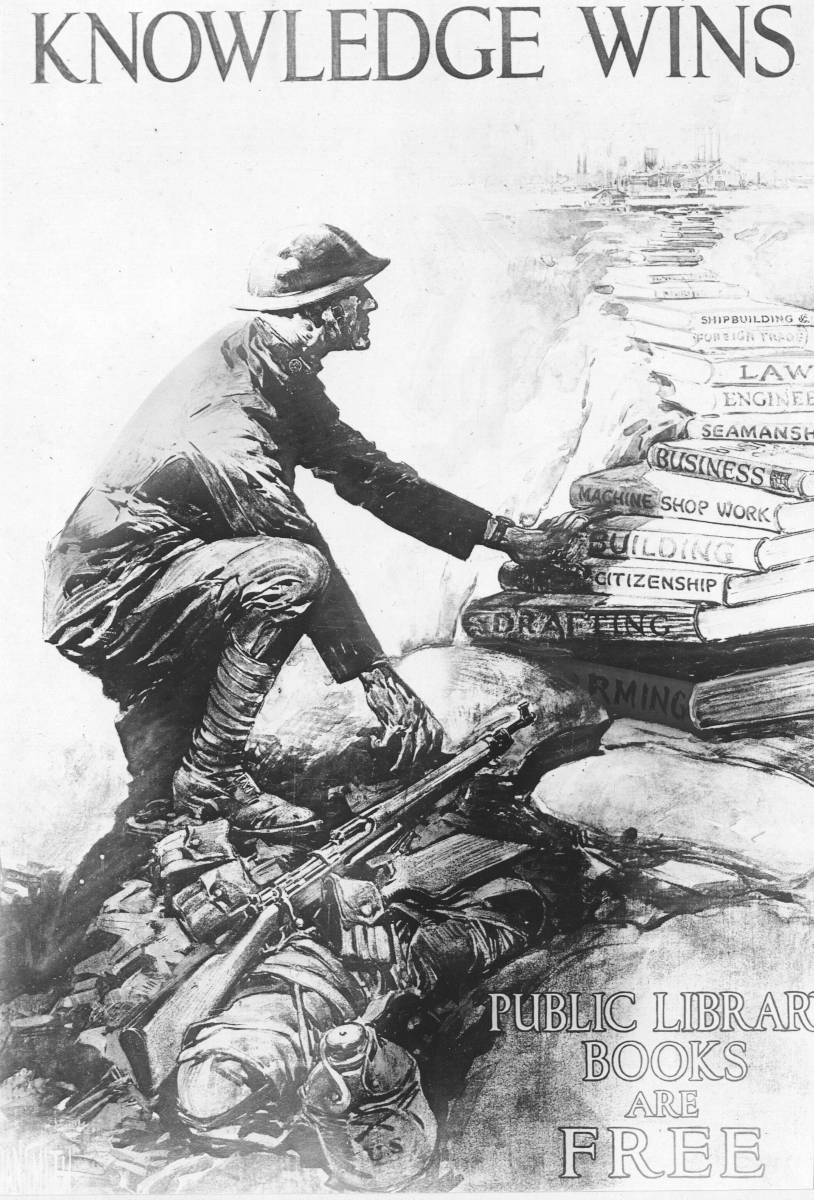

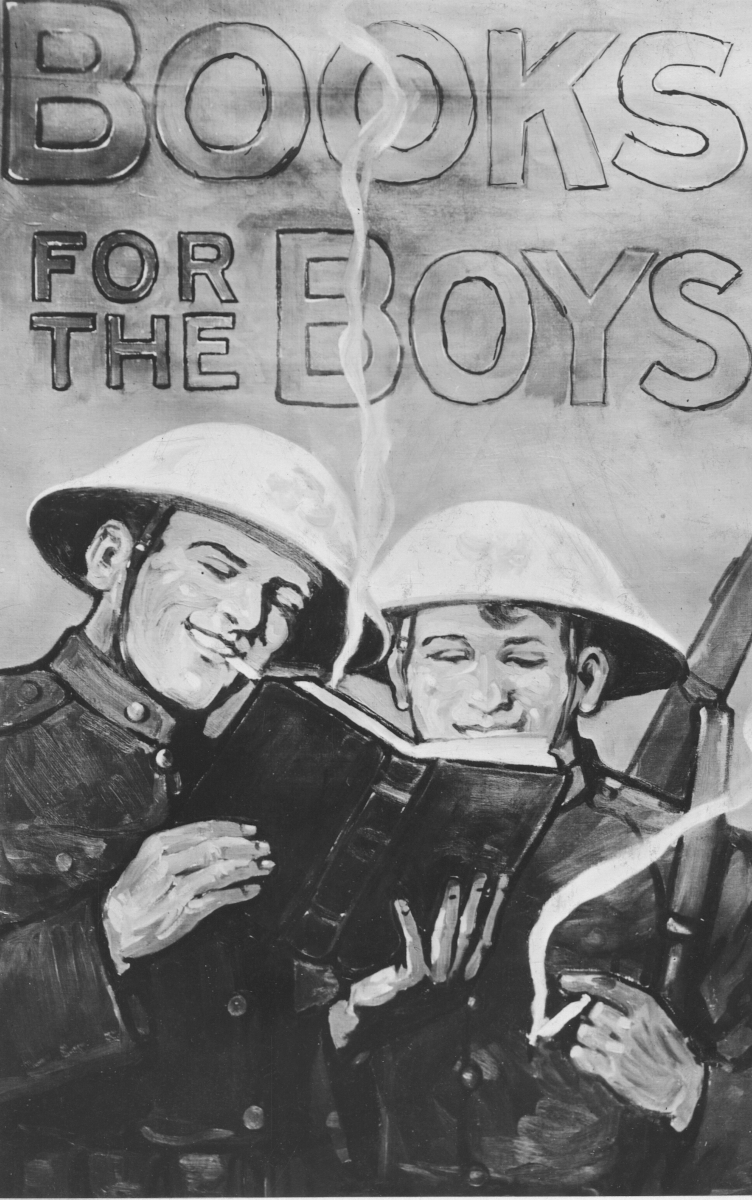

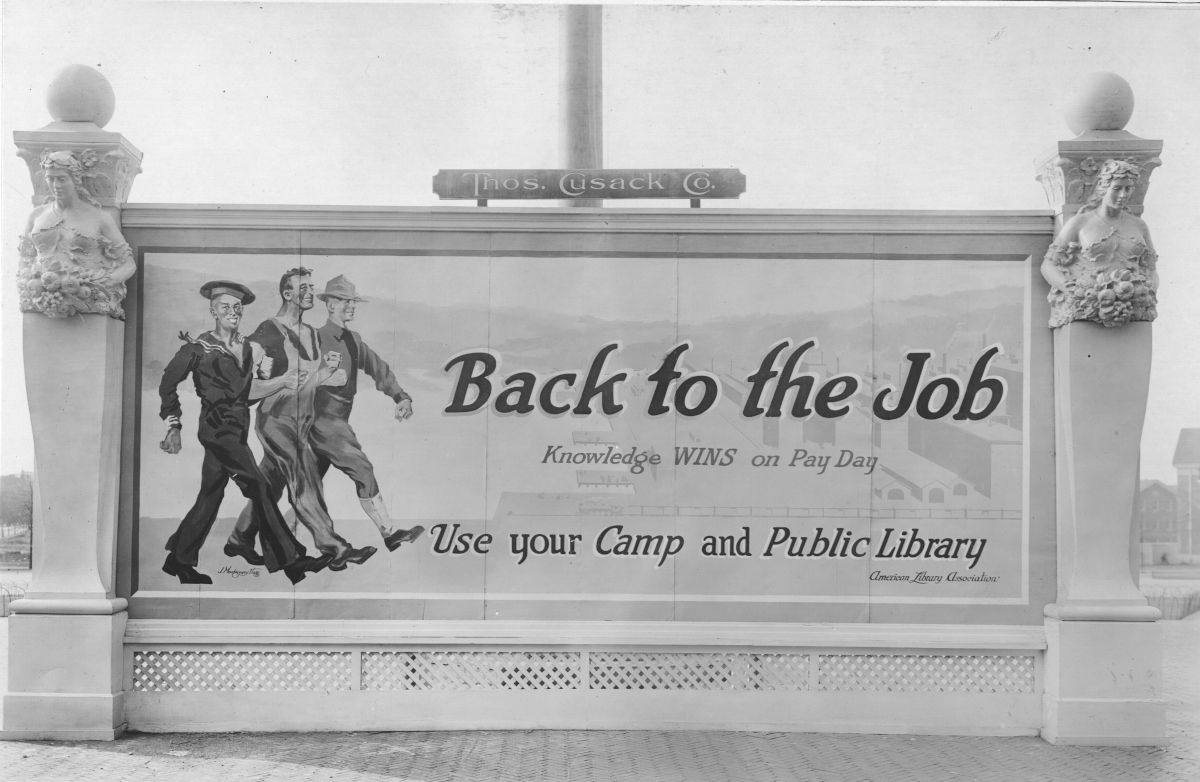

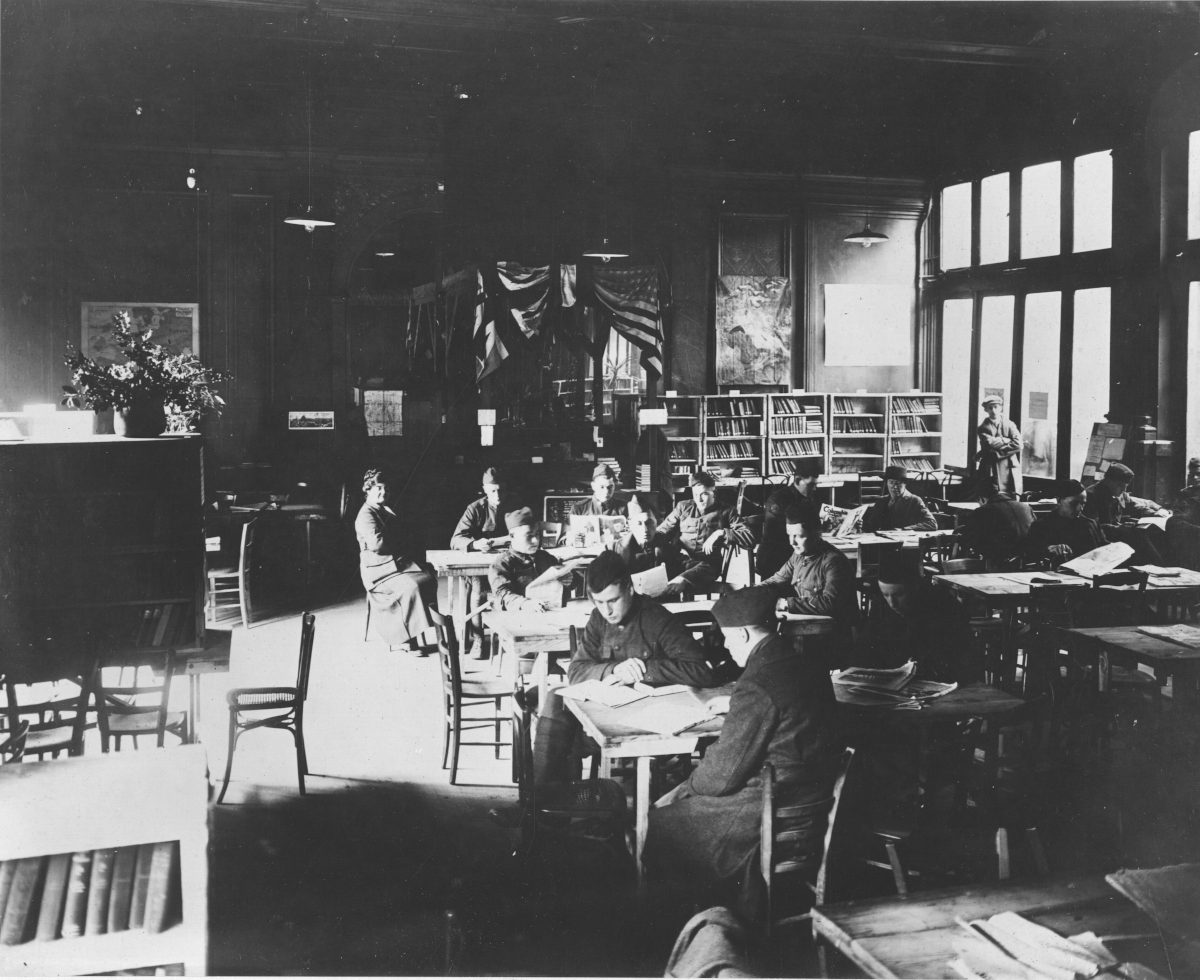

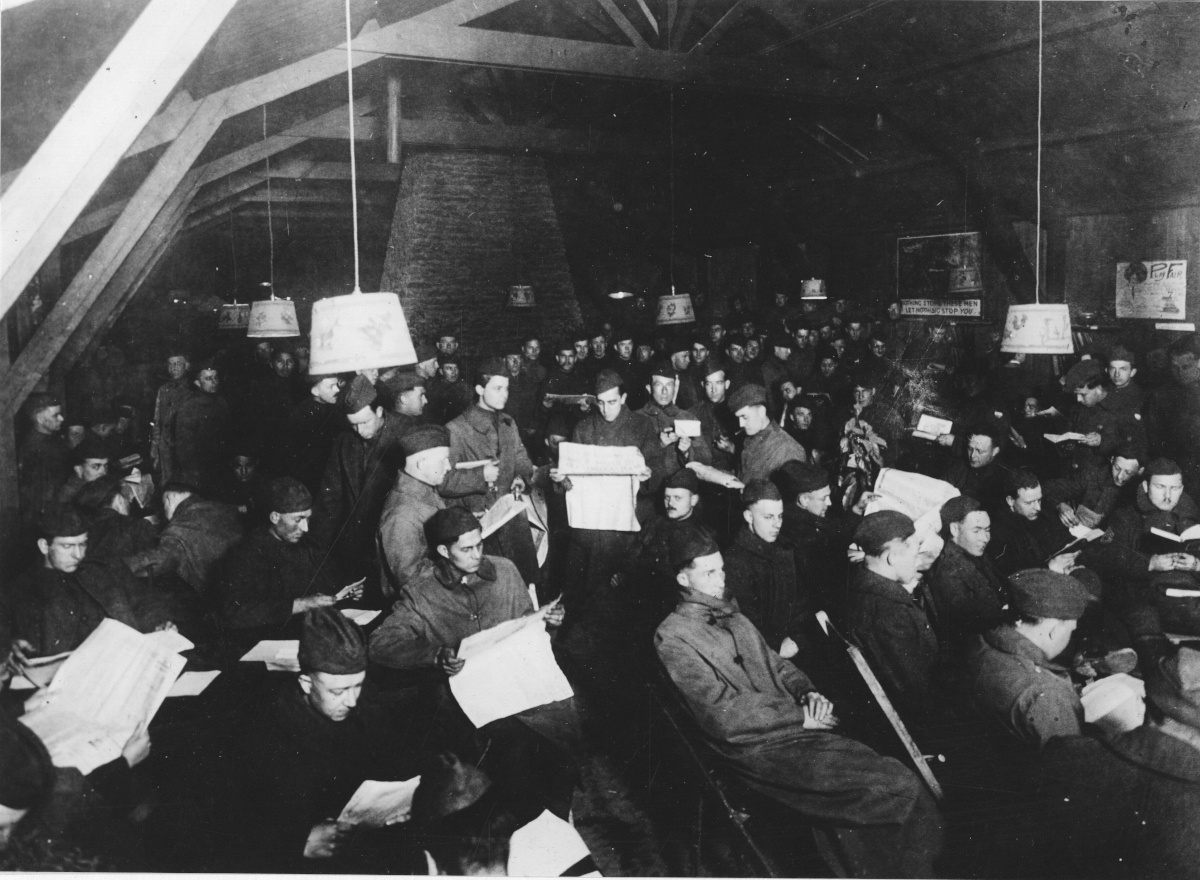

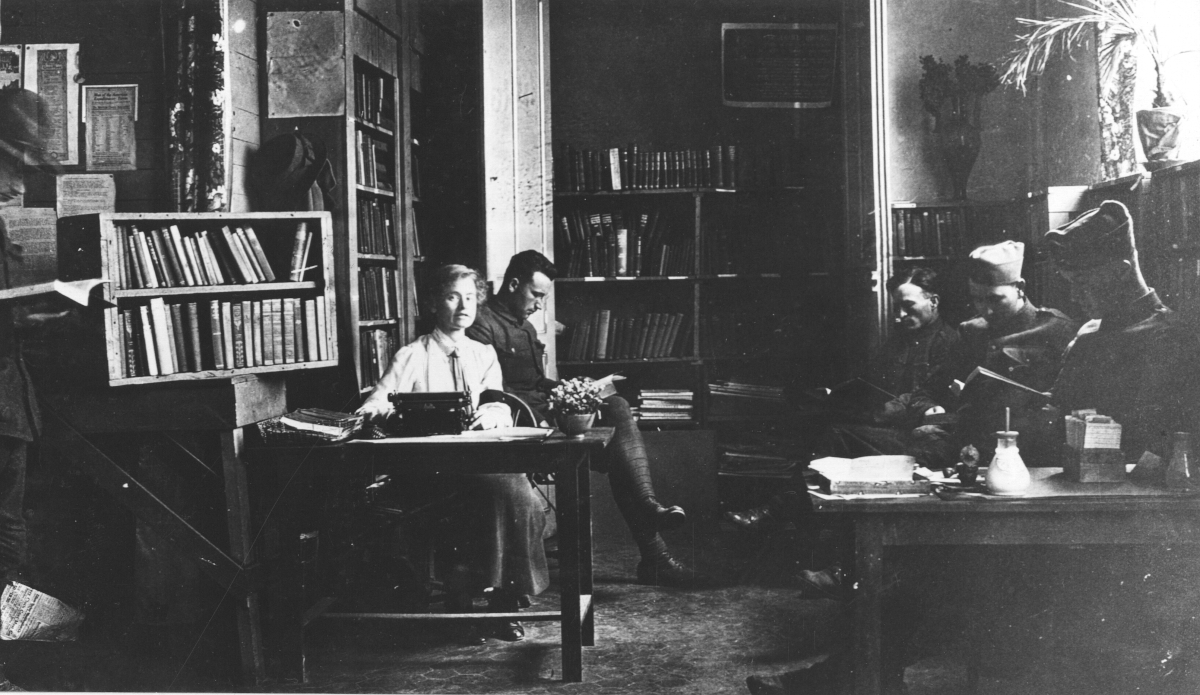

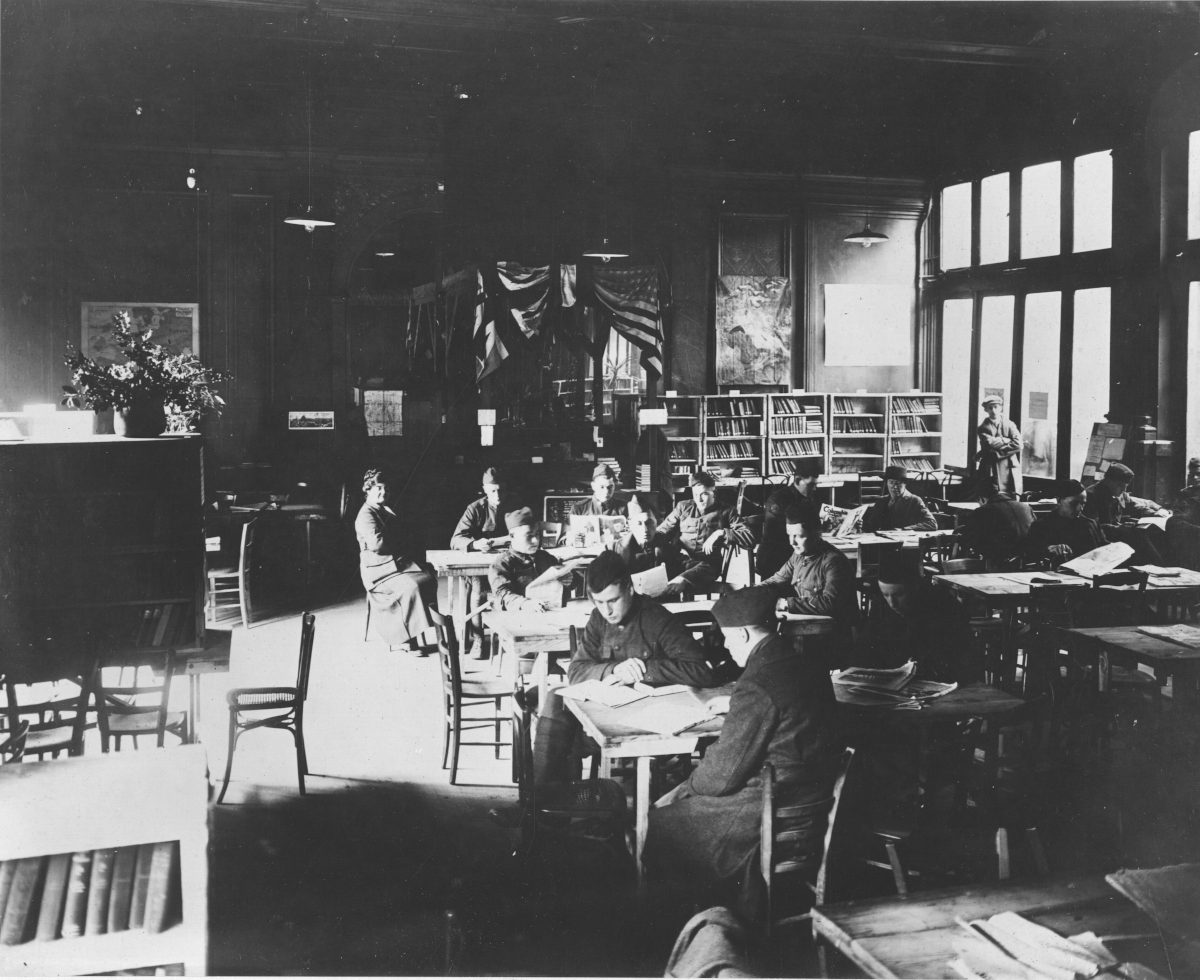

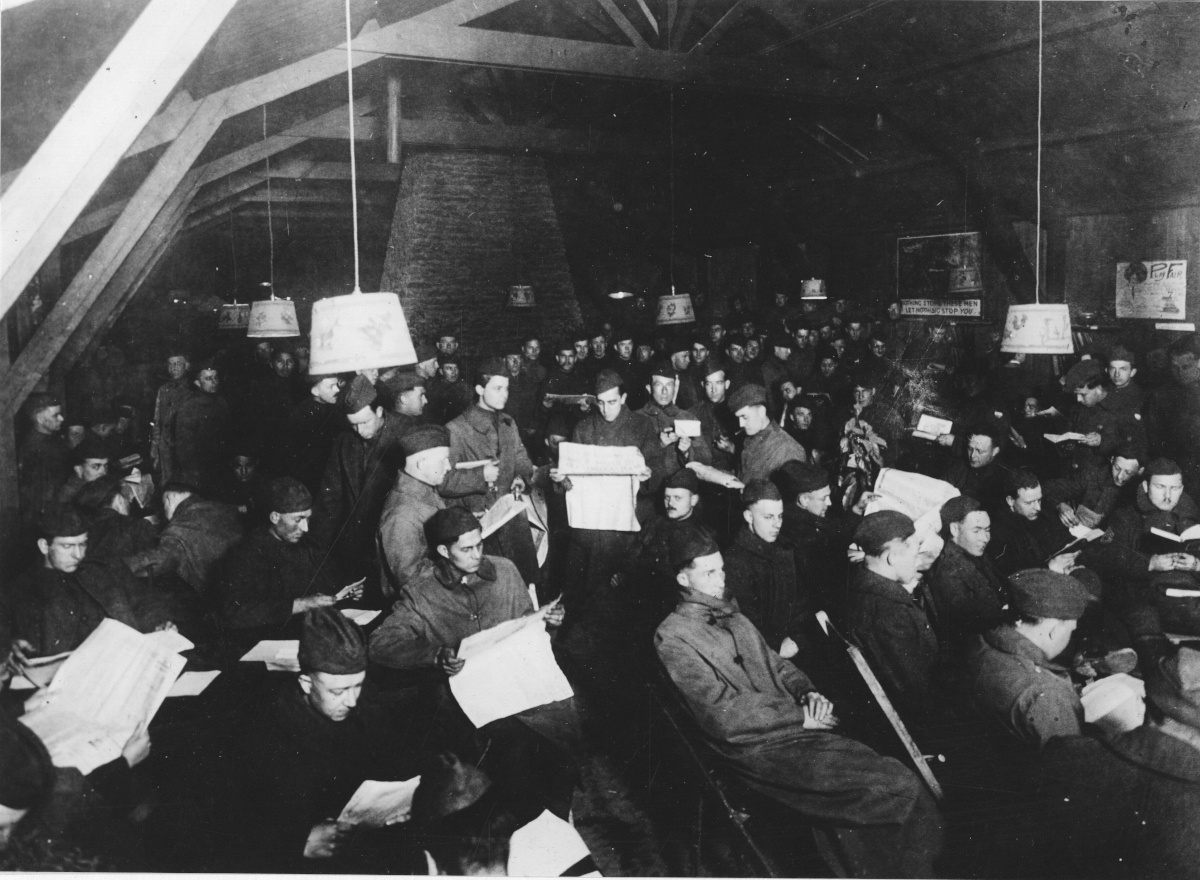

In the midst of the despair of war, the American Library Association moved forward with its mission, raising money, building library camps, and handing out books and other reading materials at more than 500 locations throughout the U.S. and Europe. The ALA solicited donations of funds and books and used libraries across the country as sites both for donations and for preparing materials for shipment.

In 1917, the ALA had more than 3,300 members, which only grew as their wartime efforts expanded and their efforts were successful. As the United States built up its army, the ALA built up its infrastructure as well. With the $5 million they received in public donations, they went about creating 36 camp libraries and providing materials to more than 500 other locations, including overseas.

In the Trenches

World War I had created horrors that ordinary soldiers could never have imagined—trench warfare, chemical weapons, machine-gun nests draped in barbed wire on the edges of broad fields of mud. Soldiers died by the hundreds of thousands on the battlefields. Many of those who survived suffered savage wounds. Some developed “shellshock”—what we now recognize as post-traumatic stress disorder—and received little to no sympathy, let alone adequate treatment.

By the time the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, the situation in Europe was very grim. In the field, German and French troops were at a near stalemate, staring each other down across a no-man’s land of mud, trenches, machine-gun nests, and barbed wire. Things got so bad that in May, 16 French army corps mutinied, refusing to leave their trenches to attack the Germans. French Field Marshal Philippe Pétain responded by calming his troops and assuring them they would hold their positions until conditions improved enough for them to advance. “We must wait for the Americans and the tanks,” he told them.

Another Chapter

The ALA’s efforts stood the test of time. By 1920, permanent libraries had been created in the Army, Navy, and Veterans Bureau. The Merchant Marines—which include U.S. Coast Guard ships, stations, lightships, and lighthouses—also formed a library association in 1921 to spread reading materials among their personnel. The American Library in Paris, which was initially established in 1918, continued on, using the 30,000 books left over after the war’s conclusion. And it doesn’t just serve as a library—it’s also a memorial and reminder of the bravery of American soldiers and the French-American alliance during the Great War.

Sadly, the Great War did not turn out to be the war to end all wars. Just over a decade later, the world was on the precipice of another global conflict. Although the ALA was not directly involved in World War II literacy efforts, their model of providing reading materials to troops was used once again. This time, the books were printed as “Armed Service Editions” (ASEs), which were 5.5″ by 6.5″ and thus small enough to fit into soldiers’ cargo pockets. The novels chosen as ASEs became some of the most poignant American classics we now know —but that’s another story!

The National Archives is the repository of multiple files of photographs documenting the American Library Association’s efforts to get reading materials into the hands of military personnel during World War I. It includes hundreds of photos of ALA libraries, both at home and abroad, and posters that served as civilian recruiting tools in soliciting donations and reading materials. Although it might seem like a small gesture, anyone who has been able to lose themselves in a good book can appreciate how much it would mean to a soldier or sailor a long way from home. The effort also served as a reminder to the troops that those back in the States had not forgotten them or their service.

View this profile on InstagramNational Archives Foundation (@archivesfdn) • Instagram photos and videos