Tyrants

Any history buff, Broadway fan, or 18-year-old can certainly sing more than a few lines from Hamilton. And now that Alexander Hamilton is a musical theater star, which historical figure is next? It just might be Edwin Booth.

A new musical tells the story of not just Edwin, the renowned actor, but also John Wilkes, his notorious brother, and Junius Brutus, their famous but onerous father. An early version of Tyrants premiered at the National Archives this October—the only time our stage has ever hosted a Broadway production. The choice of the archives as the venue was no accident, but rather a statement of how the historic events retold to music are found in its records…

In this issue

History Snack

A Play About Actors

Edwin Booth portrait, by Mathew Brady

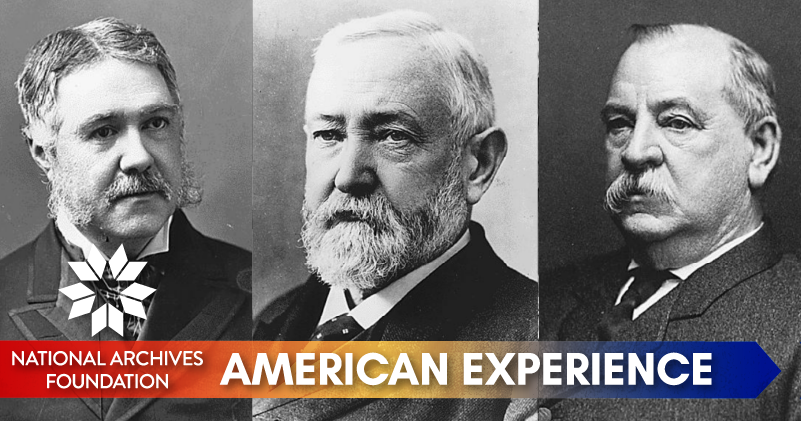

On October 6 and 7, the National Archives hosted Tyrants The Musical, a retelling of the story of the lives of esteemed actor Edwin Thomas Booth and his notorious brother John Wilkes Booth and their twisted upbringing at the hands of their father, English stage actor Junius Booth. Produced by Robert Bowman and Hundred Nights Hamlet, LLC, the musical explores the intersection of the political and the personal in the lives of the two brothers at the end of the American Civil War.

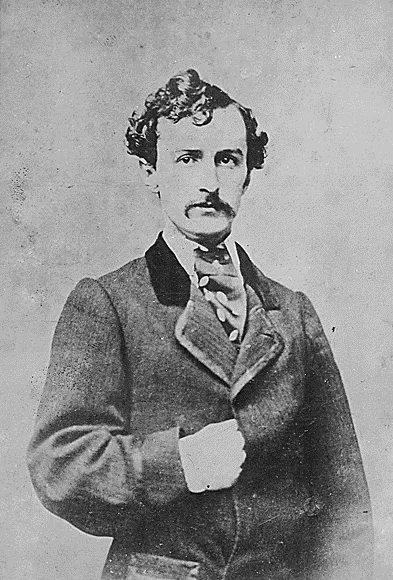

John Wilkes Booth

Junius Brutus Booth was the difficult, alcoholic father of Edwin Thomas Booth, John Wilkes Booth, Junius Brutus Booth, Jr., and their sister, Asia Booth, all of whom were born in the United States. Edwin was one of the most exalted actors of his time and a stalwart supporter of the Union cause, while his brother, John Wilkes Booth, was at best a struggling actor and an adamant Confederate. The two brothers clashed repeatedly over their political differences, to the point that they were sometimes estranged; Edwin finally banned John from his New York home. In 1859, John Wilkes Booth had actually attended John Brown’s execution at Charles Town, Virginia, standing close to the gallows to witness the hanging.

Immortal Portraits

Mathew Brady, photographer

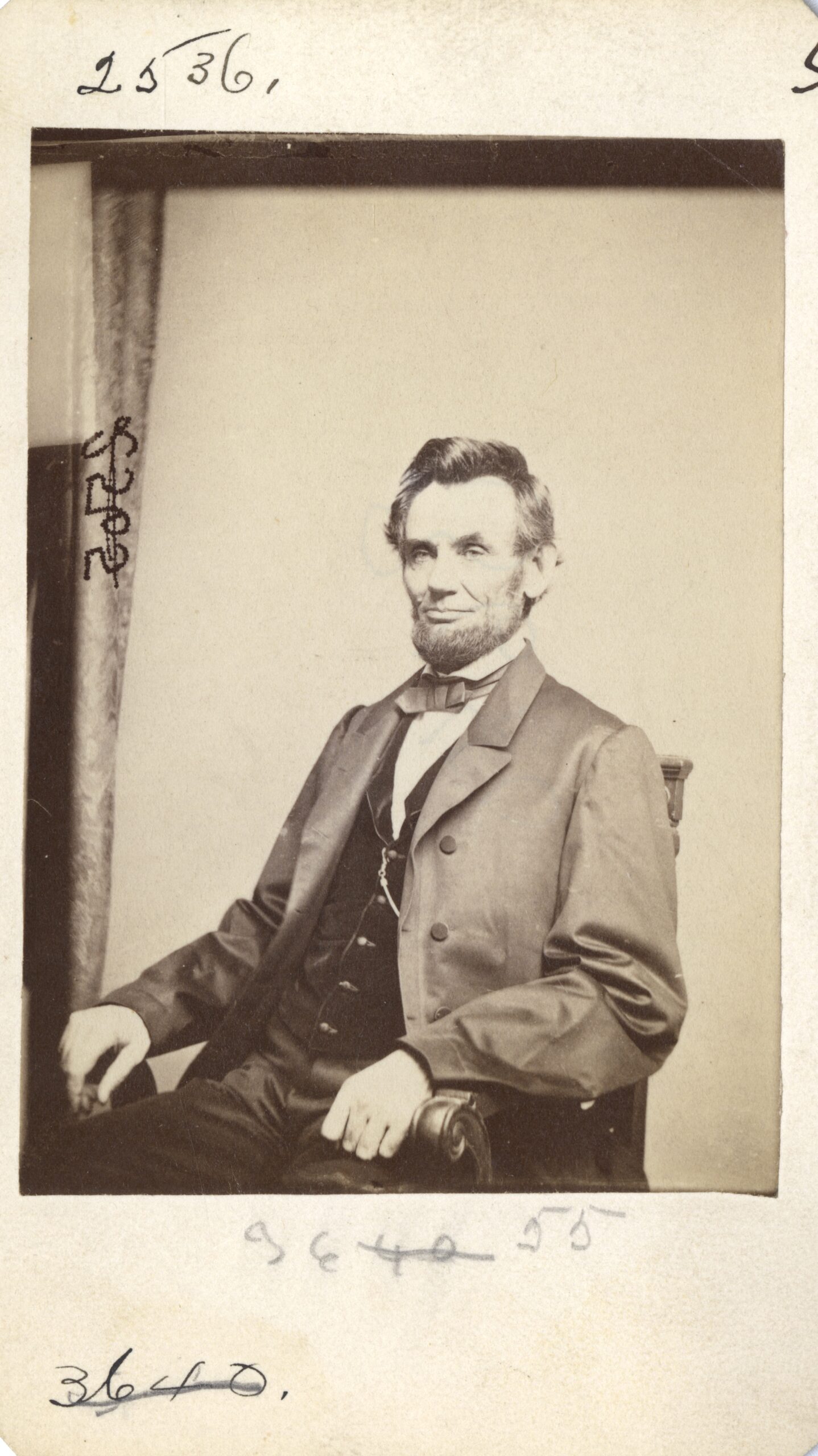

Mathew Brady’s Abraham Lincoln portrait

National Archives Identifier: 167249680

The National Archives is the repository of a remarkable group of objects related to this turbulent time in our country’s history. Among them are three portraits by Mathew Brady, the preeminent photographer who arose to prominence during the American Civil War, when many people raced to have their portraits made. In those perilous times, soldiers going to war wanted to have their likenesses preserved for their loved ones to remember them by, in case they did not return, while actors had more pragmatic reasons for having their “headshots” made.

Mathew Brady’s iconic image of Abraham Lincoln, taken on January 8, 1864, depicts the President in three-quarter pose, seated for a moment in the midst of the most dramatic period of the war. Lincoln plainly had no personal vanity. Brady’s portrait of Edwin Booth is a profile shot of a rumpled individual who nevertheless was one of the most acclaimed actors of his generation.

Conspiracy Unraveled

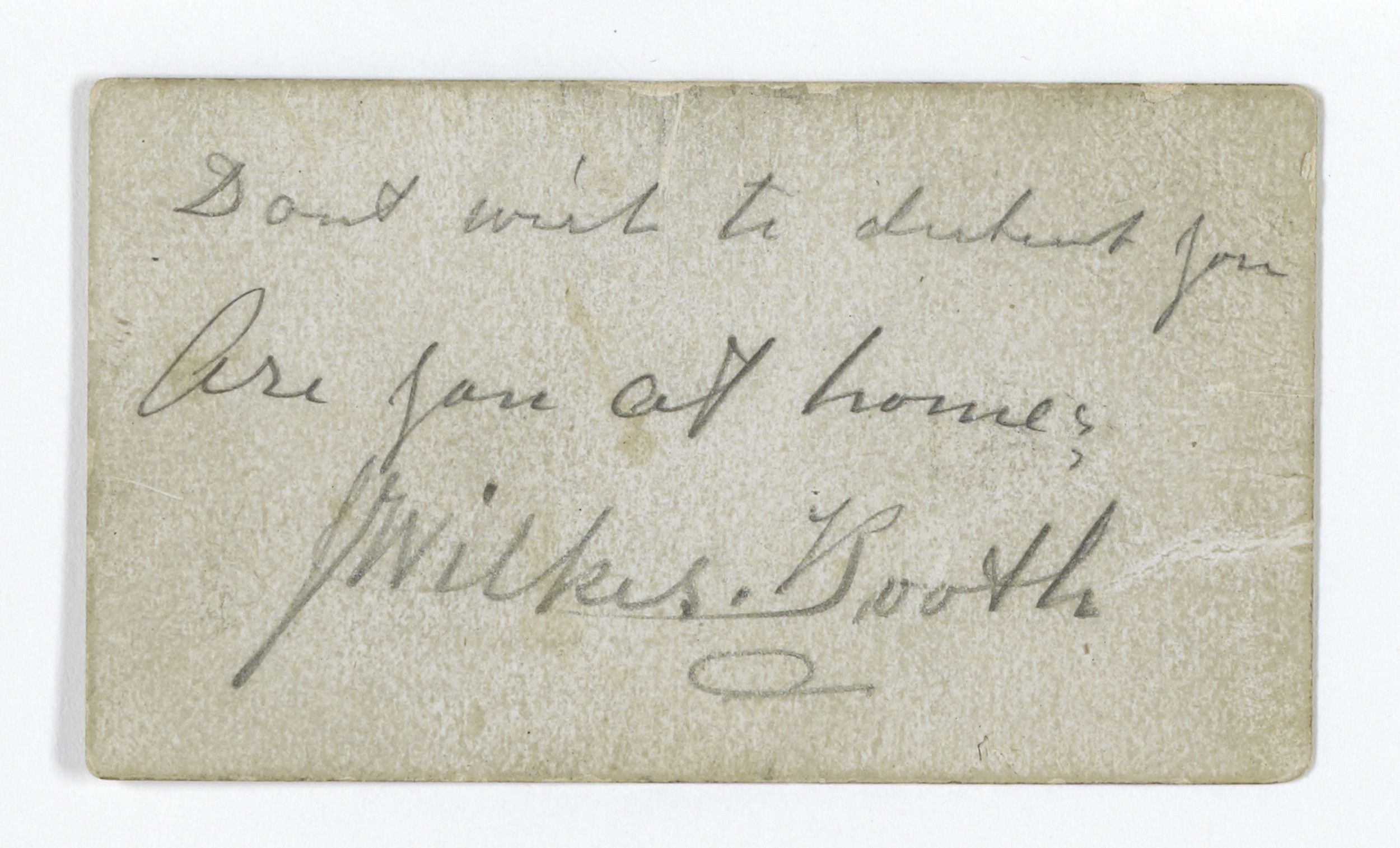

John Wilkes Booth calling card

John Wilkes Booth was the mastermind of a conspiracy that began as a plot to kidnap Abraham Lincoln. As time went on, the plan morphed into a greater intention to execute Lincoln, Secretary of State William H. Seward, and Vice President Andrew Johnson. Rather creepily, John Wilkes Booth left his calling card at Vice President Andrew Johnson’s hotel in Washington on the afternoon of April 14, 1864, just before he shot Lincoln. The message he inscribed reads, “Don’t wish to disturb you. Are you at home? J. Wilkes Booth.”

Secretary of State William Seward

On the evening of April 14, 1865, Booth succeeded in killing Lincoln, but Lewis Powell only wounded Seward, and George Atzerodt completely lost his nerve and spent the evening drinking rather than trying to kill Johnson.

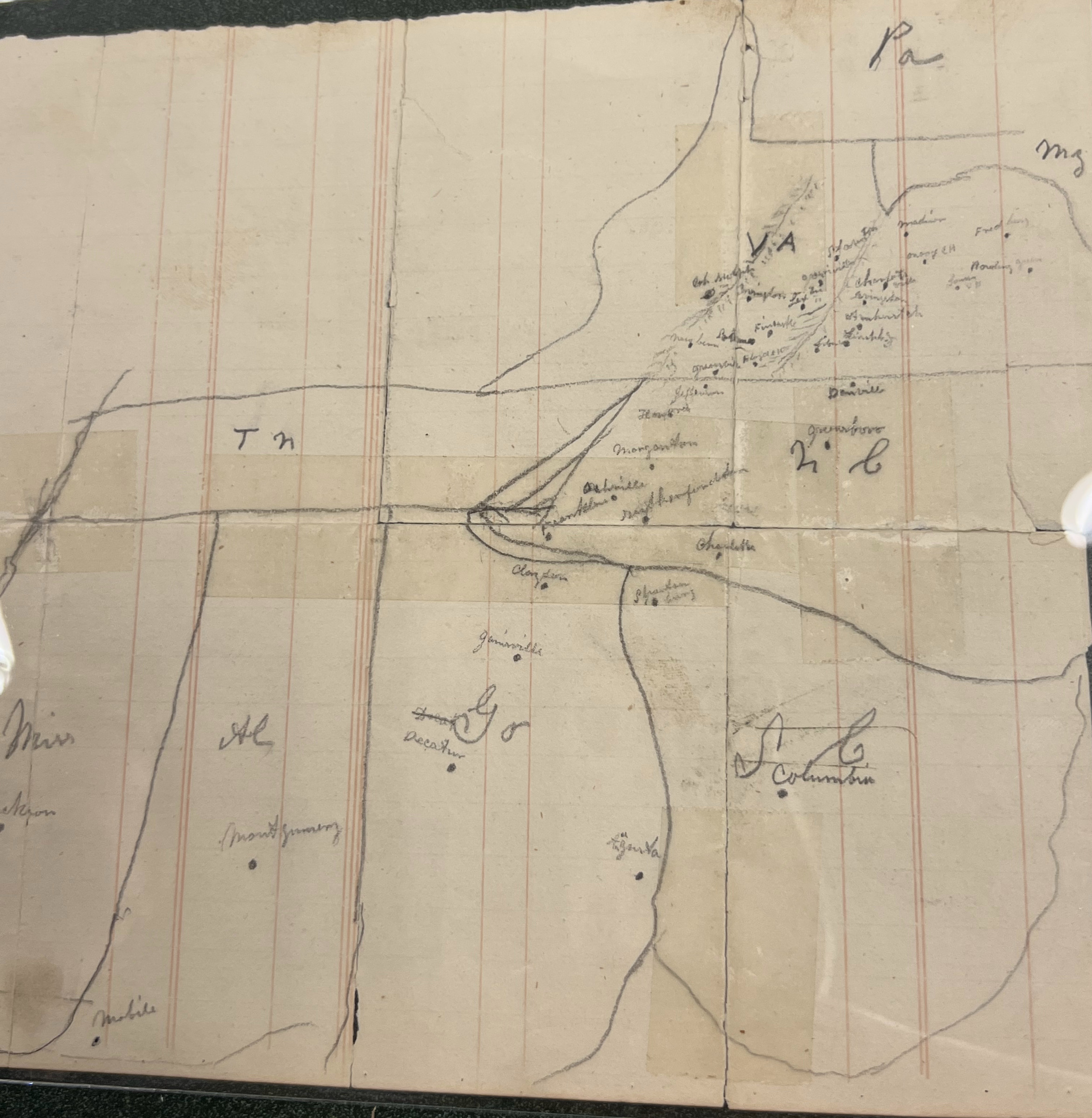

As he leapt from the balcony to the stage of Ford’s Theatre, Booth shouted, “Sic semper tyrannis! (‘Thus always to tyrants’),” which gives the musical its name. Booth escaped from the alley behind the theater on horseback to southern Maryland, planning to cross the Potomac River into Virginia. He didn’t count on several developments, however—first, he fractured his leg, either when he jumped from the balcony or in a horse accident on the trip into Maryland. On April 16, he sought treatment from Dr. Samuel Mudd at St. Catherine, who set Booth’s leg.

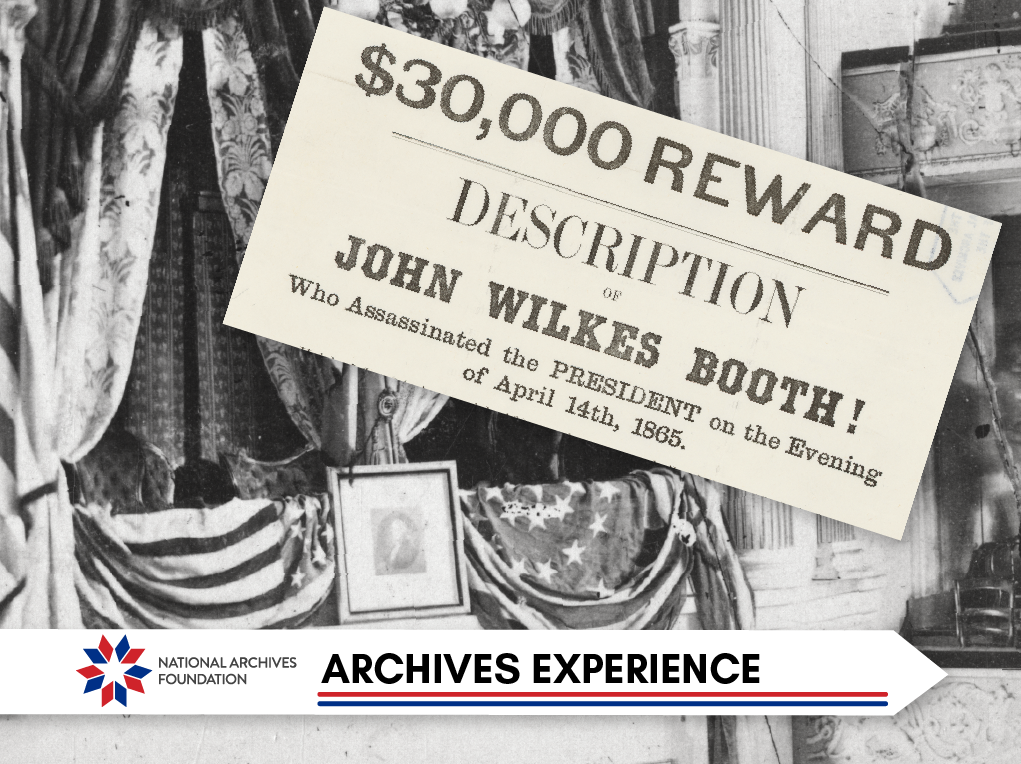

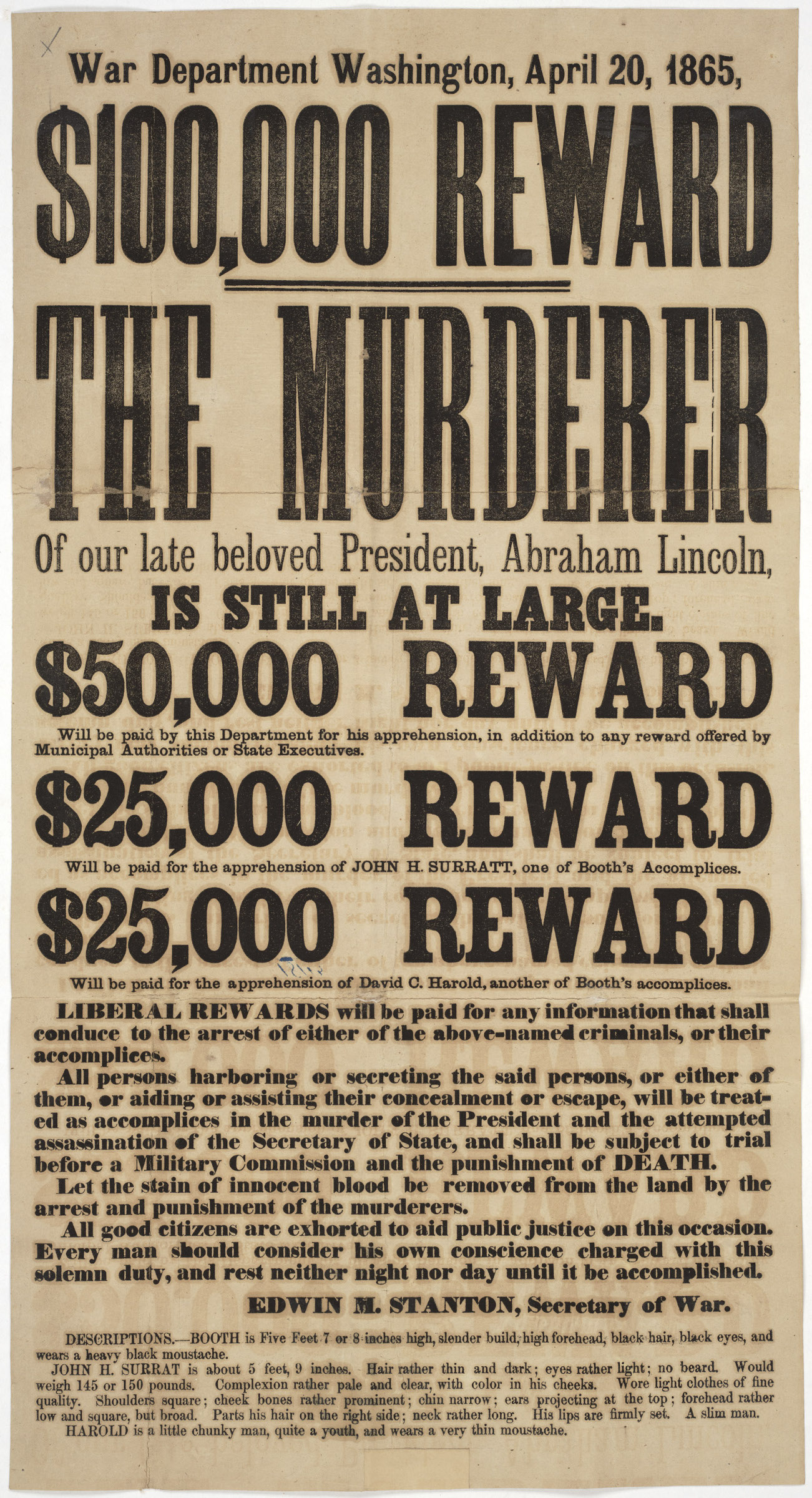

Booth also didn’t count on the massive federal manhunt that immediately arose in response to the assassination. A huge bounty was placed on his head that eventually reached $100,000, and federal troops were combing the woods he was hiding out in practically from the moment he escaped Washington. From St. Catherine, Booth slipped down into the Maryland woods, where he hid out until April 21, when he finally crossed the river over into Virginia. He kept apprised of the local feeling by reading the newspapers and was stunned to learn that he was considered a traitor to his country.

John Wilkes Booth hand-drawn escape map

John Wilkes Booth wanted/reward poster

“With every man’s hand against me, I am here in despair,” he wrote in his diary. “And why; For doing what Brutus was honored for… And yet I for striking down a greater tyrant than they ever knew am looked upon as a common cutthroat.”

Booth arrived at Richard H. Garret’s farm on April 24, where he hid for several days. He was finally captured on April 26. Despite Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s express order that Booth be captured and returned to Washington alive, Sergeant Boston Corbett shot him in the back of the head, severing his spinal cord and paralyzing him. Booth died two hours after being shot. Mathew Brady’s portrait of Corbett is the third and final one of this group.

Corbett was court-martialed for shooting Booth against orders, but he was discharged on the grounds that he fired his weapon in self-defense. He left the army in 1865 and had a difficult time holding a job thereafter, largely because of his notoriety as the avenger of Abraham Lincoln.

Another portrait of Sergeant Corbett, also by Mathew Brady

National Archives Identifier: 526798

Tyrants actor A.J. Shivley, who plays actor Edwin Booth, reads the letter that Edwin wrote to the American people in the wake of the assassination

(2 minutes 1 seconds)

View this profile on InstagramNational Archives Foundation (@archivesfdn) • Instagram photos and videos