The Raid for Freedom

The debate over John Brown and his deadly actions at Harpers Ferry is still alive today. Many historians still question his behaviors and whether he was a devoted revolutionary who went to any length in the name of freedom, or a traitor. One fact that’s well agreed-upon is that he was an anomaly for his time—a white man putting his life on the line to end slavery was a position that not even the most ardent abolitionists took. Today is the anniversary of a particularly destabilizing event in the 19th century, the raid on Harpers Ferry…

In this issue

Riding in a wagon packed with guns and ammunition, fully prepared to wage war…

The South created exactly the kind of martyr that the abolitionist movement had been looking for…

History Snack

Background—“Bleeding Kansas” and John Brown

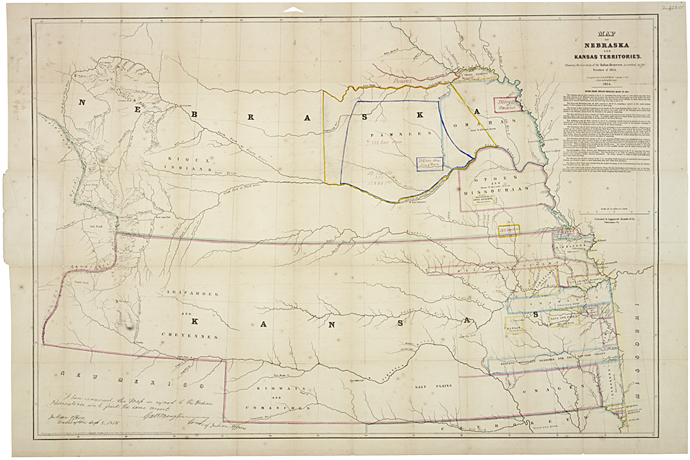

Territories of Kansas and Nebraska

NARA’s The Center for Legislative Archives

When John Brown arrived in 1855 to fight on the side of the antislavery movement in the Kansas territory, he had already established several very successful farms and tannery businesses in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Massachusetts, and New York. He had also been married twice and had fathered 20 children, several of whom had died very young. Born in 1800 in Torrington, Connecticut, Brown had studied for the ministry as a young man and had become a well-known preacher, and he was a very prominent abolitionist who had run several outposts on the Underground Railroad from his homes. He and his son-in-law Henry Thompson went to Kansas to join his five sons there, riding in a wagon packed with guns and ammunition, fully prepared to wage war in the conflict that swiftly became known as “Bleeding Kansas.”

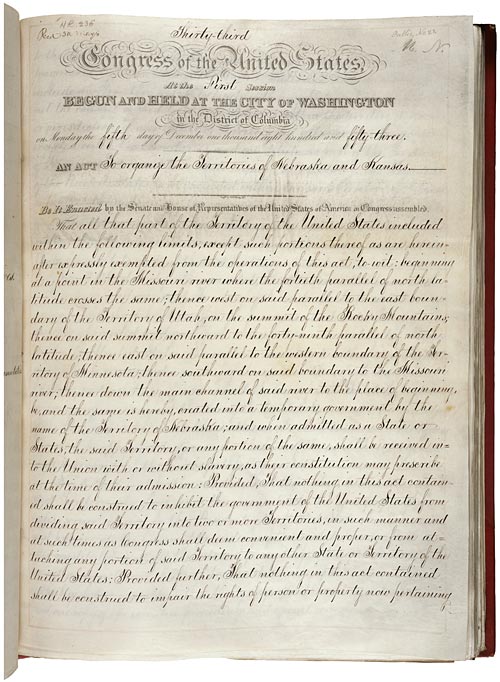

Kansas-Nebraska Act , 1854

NARA’s Milestone Documents

Kansas Territory was engulfed in a full-blown civil war that lasted from 1854 until 1860 over whether it would enter the union as a slave or a free state. The voters of Kansas were supposed to decide the question, but voter fraud in favor of making Kansas a slave state was rampant in the territory. On May 21, 1856, Lawrence, the center of the antislavery movement in Kansas, was attacked by a sheriff-led posse that destroyed the Free State Hotel and two abolitionist newspapers. Only one person died in the attack, a “border ruffian”—a proslavery man who had entered Kansas to ensure it became a slave state. John Brown was absolutely incensed by the attack on Lawrence and equally angered by the antislavery forces’ lackluster response to the raid.

In retribution, Brown, his sons, and other abolitionists dragged five pro-slavery settlers out of their homes and killed them in front of their families in Franklin County, just north of Pottawatomie Creek. The Pottawatomie massacre set off the bloodiest stretch of “Bleeding Kansas,” a three-month period during which 29 people were killed.

Brown participated in two more actions in Kansas, the Battle of Black Jack in June and Osawatomie in August, which resulted in federal warrants being issued for his arrest. He slipped out of Kansas and headed back east, where he again began planning a major attack on the institution of slavery, which he’d been working on for at least 20 years. He had finally set his sights on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, where thousands of firearms were stored.

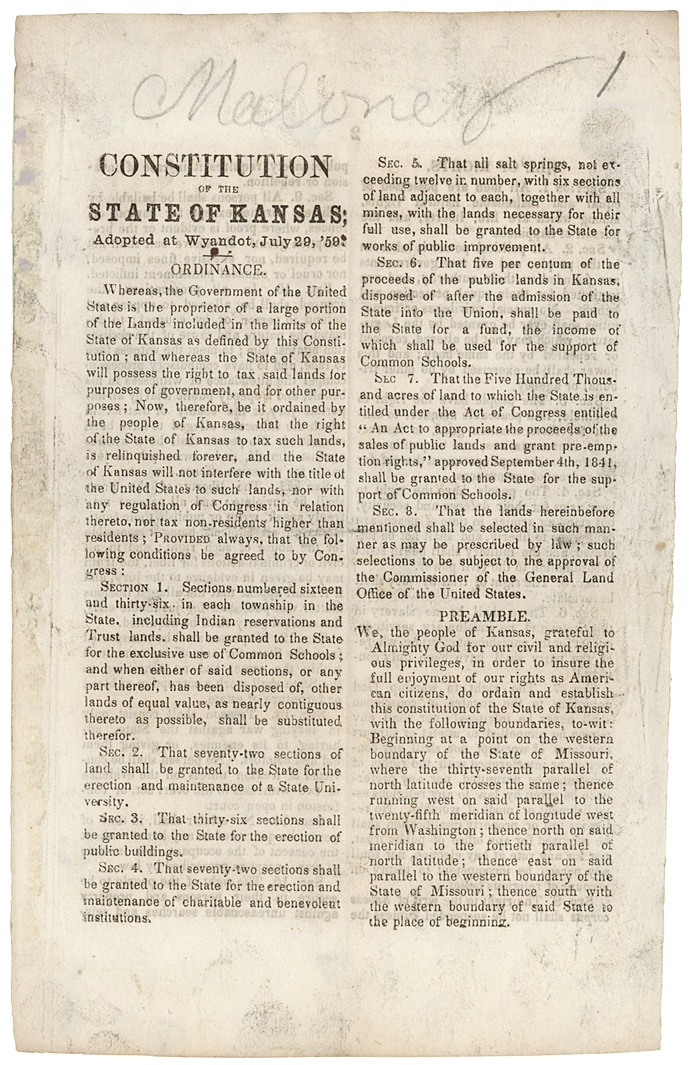

Wyandotte Constitution

NARA’s The Center for Legislative Archives

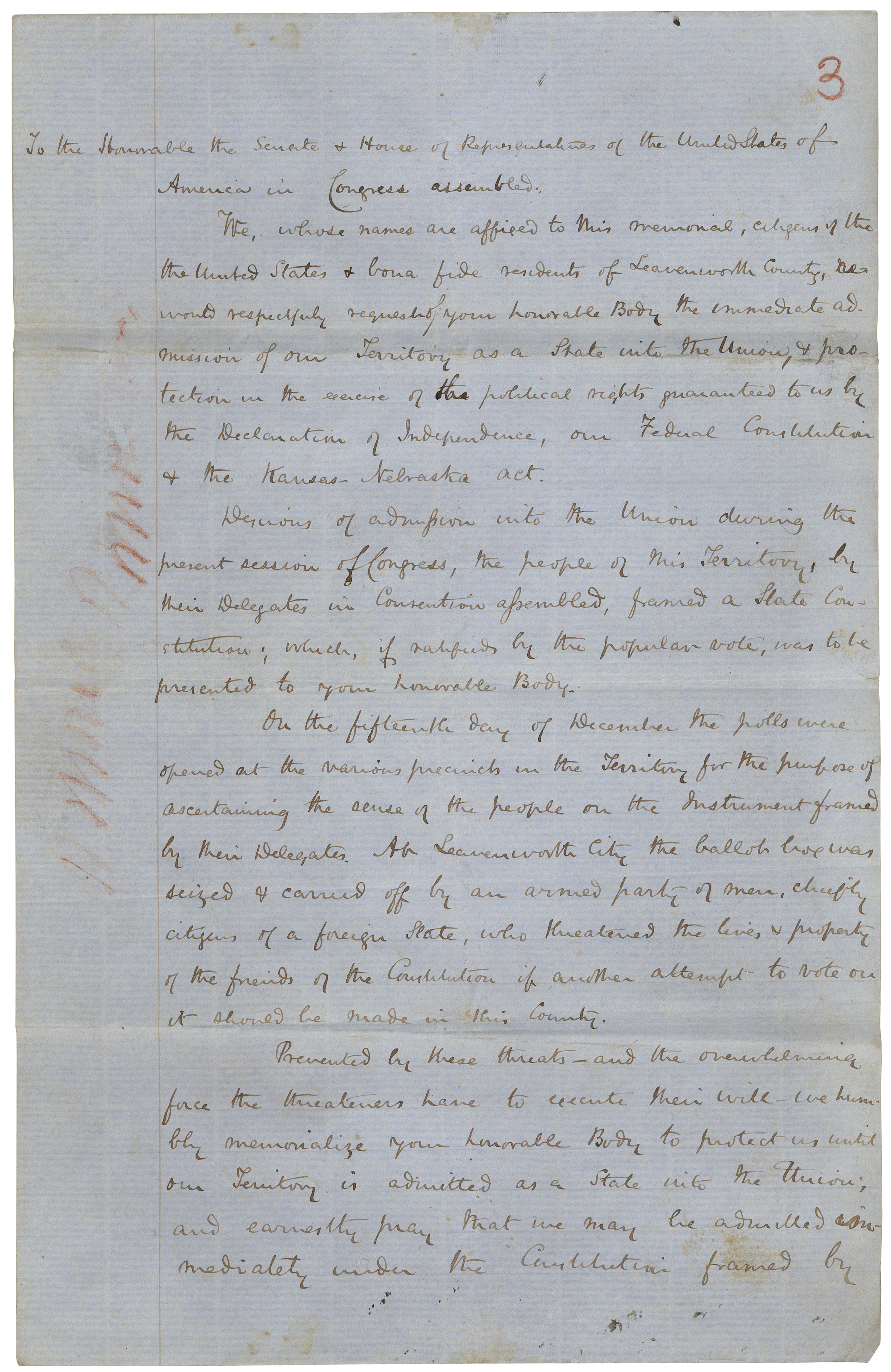

Memorial for residents of Leavenworth

NARA’s The Center for Legislative Archives

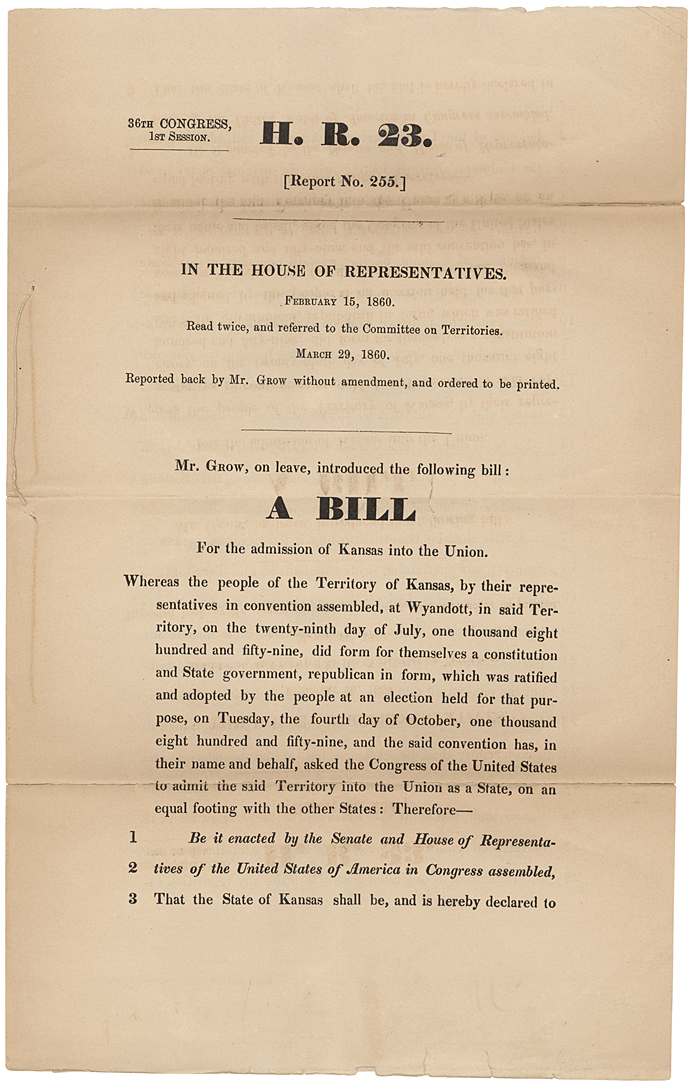

Kansas admitted as a free state

NARA’s The Center for Legislative Archives

Organizing the Raid

John Brown was an evangelical Christian who truly believed that violence was necessary to destroy the institution of slavery. He was firmly convinced that he was an American Moses, destined to lead all slaves to freedom. He meant to lead a raid on Harpers Ferry that would cripple slavery and inspire the enslaved on Southern plantations to throw off their chains and run away to the free states of the North.

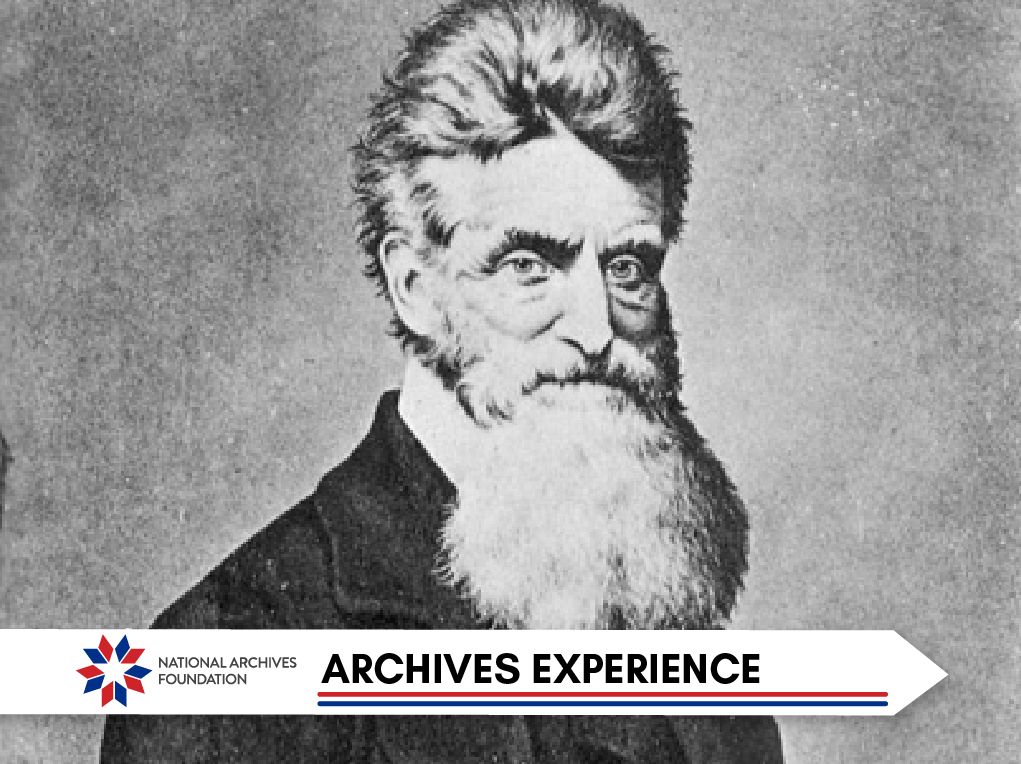

Brown did not talk about his plans with any of his followers. When he left Kansas, he quit shaving, growing a bushy beard to help change his appearance. Throughout 1857 and 1858, he traveled through Connecticut, New York, and Massachusetts to raise money and gain political clout, meeting with prominent abolitionists, including William Lloyd Garrison, Samuel Gridley Howe, Franklin B. Sanborn, Samuel G. Howe, M.D., George L. Stearns, Gerrit Smith, Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Mary Ellen Pleasant, an African American entrepreneur and abolitionist.

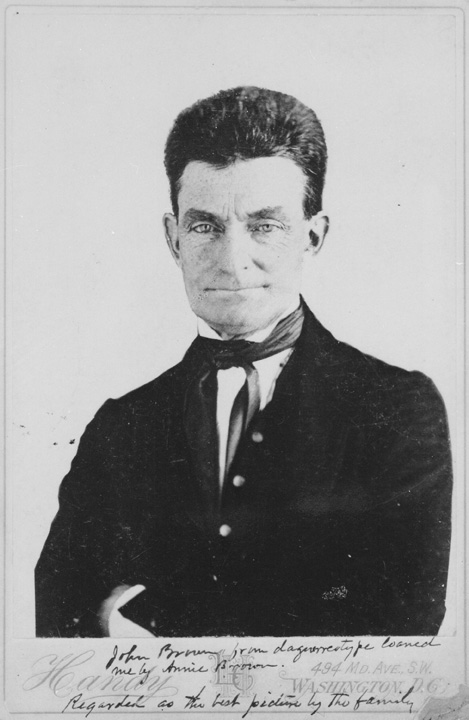

John Brown portrait–1850s

Source: NARA’S Prologue Magazine

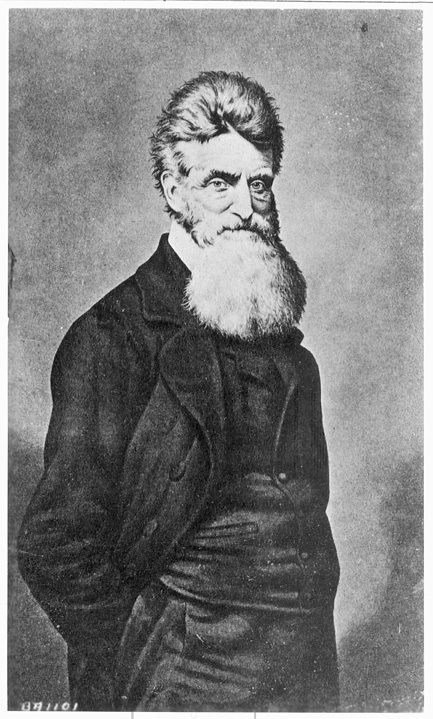

John Brown portrait

Source: NARA’S Prologue Magazine

However, Brown kept the details of his plans close to the vest. He did spend an entire day discussing the raid with Frederick Douglass, one of the most prominent Black leaders of the time, trying to persuade Douglass to join him at Harpers Ferry. Douglass quite pointedly refused, telling Brown that the plan was suicidal.

Through the efforts of the Massachusetts Committee, Brown procured 200 Sharps rifles and ammunition. Other weapons he managed to gather up included shotguns, muskets, and pikes. Brown planned to use these weapons to take the armory at Harpers Ferry and then to use the weapons stored at the armory to equip his troops.

Brown and his followers then went to Chatham, Ontario, where, on May 12, 1859, he convened a constitutional convention attended by 34 Black and 12 white people. It was here that Brown met Harriet Tubman.

Brown introduced his provisional constitution, which he had written while he was a guest at Frederick Douglass’ house in February 1858. The constitution called for the creation of a new state in the Appalachian Mountains populated by escaped slaves and others devoted to freeing the enslaved.

John Brown writes a provisional constitution and ordinances for the people of the United States

National Archives Identifier: 3819337

Nearly all the delegates signed the constitution, but almost none of them volunteered to join Brown’s raid. Brown then traveled to New York City, where he met Hugh Forbes, an English mercenary whom Brown hired to drill his forces in preparation for the raid. However, Forbes grew dissatisfied with his arrangement with Brown and proceeded to talk about Brown’s plans to Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson and other prominent individuals. The information leak put Brown’s plans in serious jeopardy.

Furthermore, Brown lost contact with many of his Canadian supporters, and he left for Kansas, where he joined up with James Montgomery, an abolitionist who was fighting the proslavery forces in Missouri. Brown led the Battle of the Spurs, at Netawaka, Kansas, on January 31, 1859, in which he freed 11 slaves and captured two white men and several wagons and horses. The governor of Missouri promptly put a price on Brown’s head, and Brown headed back east with the slaves in tow, bound, at last, for Harpers Ferry.

Brown visited his family in North Elba, New York, before he left for Hagerstown, Maryland, where he spent the night at the Washington House on June 30, 1859. From Hagerstown, Brown and his group moved to Kennedy Farmhouse in Washington County, Maryland, a few miles away from Harpers Ferry. They stayed there until mid-October, preparing for the raid.

View of Harpers Ferry

Source: NARA’s Prologue Magazine

Events of the Raid

Counting Brown himself, 22 men participated in the raid on Harpers Ferry, including three of his sons and five Black men. This was a much smaller group than Brown had hoped to assemble. They attacked on the night of October 16, 1859, starting by cutting the telegraph wires and taking the armory, which was guarded by a single watchman. They then took hostages at local farms and told the slaves that they were freed. So far, so good.

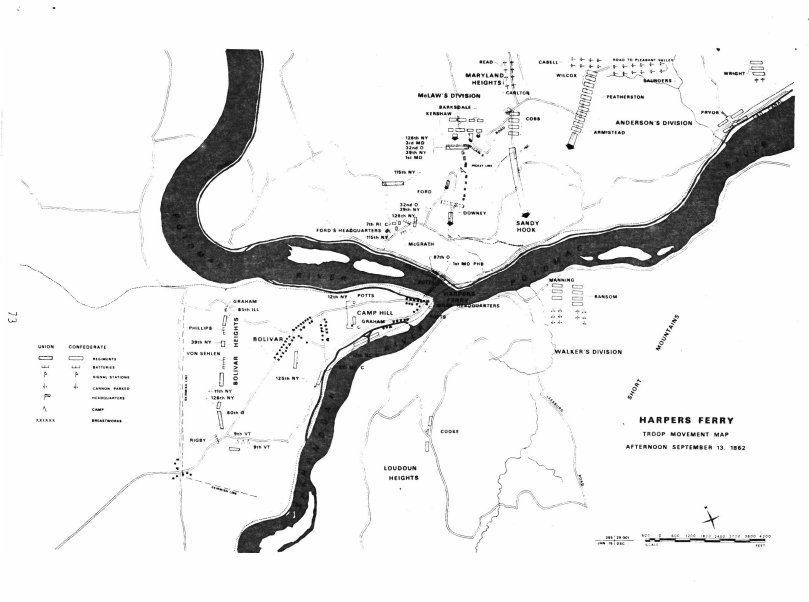

But their plans started to go awry when an eastbound Baltimore and Ohio train reached through the town. Brown stopped the train and then, for some unexplained reason, let it pass. When it reached the next town, where the telegraph was still functioning, the conductor wired news of the raid to the railroad’s headquarters in Baltimore. By the morning of October 18, First Lieutenant Israel Greene’s company of U.S. Marines had surrounded Brown’s raiders, who were holed up in the engine house. Backed up by the forces of Colonel Robert E. Lee of the United States Army, Army First Lieutenant J. E. B. Stuart ordered Brown to surrender. Brown refused, and the Marines proceeded to break down the door. The whole operation was over in three minutes.

Brown’s forces killed five people and wounded 10. Of his men, four escaped and the rest were killed or captured. The state of Virginia tried and convicted Brown of treason in a trial that started on November 2 and lasted a week in Charles Town. President Buchanan declined to involve the federal government in the legalities because the governor of Virginia, Henry A. Wise, contended that Brown’s actions made him the enemy of the slaveholders of the state of Virginia rather than of the nation as a whole. What went unspoken was the fact that a federal trial would doubtless have stirred up protests by abolitionists on a widespread national scale.

Company E and 22nd NY State Militia near Harpers Ferry

National Archives Identifier: 524561

Company of infantry on parade near Harpers Ferry, VA

National Archives Identifier: #######

Maryland Heights at Harpers Ferry

National Archives Identifier: 524577

The jury convicted Brown of treason in 45 minutes, and the judge sentenced him to hang on December 2. Brown was the first man convicted of treason in the United States up until that point. All of his men who survived the raid and were captured were also tried and executed.

Brown made good use of the last month of his life, talking to reporters and writing letters, many of which were printed in newspapers. Several plots to rescue him were uncovered, and Victor Hugo wrote an impassioned plea for his pardon that the press on both sides of the Atlantic published. However, Brown said he did not want to be pardoned, and Southern politicians feared the rise of hundreds, if not thousands, of John Browns bent on leading slave rebellions throughout the South if he was set free.

On December 2, 1859, the day of his execution, John Brown rode to the gallows sitting atop his coffin in a wagon. He had written out his last words, which proved prophetic indeed: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.”

He was hanged at 11:15 a.m. and pronounced dead about half an hour later. His body was transported to North Elba, New York, and buried there on the family farm. Afterward, the farm was sold except for the burial plot, and his family scattered across the country.

Aftermath

In the wake of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, the South began to rebuild its militia system in anticipation of more slave rebellions. The northern abolitionist movement found in John Brown the martyr he had hoped to become.

It is worth considering whether by insisting that Brown be executed, the South created exactly the kind of martyr that the abolitionist movement had been looking for. After all, a mere two years later, Union troops were singing “John Brown’s Body” as they marched to war against the Confederacy, and many of his contemporaries praised him to the skies. William Lloyd Garrison, who disapproved of Brown’s violent methods, wrote on the day he was hanged, “whenever commenced, I cannot but wish success to all slave insurrections.”

Frederick Douglass, who tried to convince him that the Harpers Ferry raid was a suicide mission, said that Brown’s “zeal in the cause of my race was far greater than mine—it was as the burning sun to my taper light—mine was bounded by time, his stretched away to the boundless shores of eternity. I could live for the slave, but he could die for him.” Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “[John Brown] will make the gallows glorious like the Cross.” And years later, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote the raid shone as “a great white light—an unwavering, unflickering brightness, blinding by its all-seeing brilliance, making the whole world simply a light and a darkness—a right and a wrong.”

Still, historians have debated endlessly about whether Brown was a revolutionary, a martyr to his cause, or simply insane. The answer one arrives at most likely depends on one’s attitude toward the methods Brown embraced, which were exceptionally violent even by the standards of his own day, and the war that followed his actions, both in Kansas and at Harpers Ferry.

Today, Harpers Ferry is a town almost frozen in time. Visitors can see original Civil War-era dwellings, businesses, and the armory, set against the beautiful backdrop of the Appalachian Mountains and both the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers.

View this profile on InstagramNational Archives Foundation (@archivesfdn) • Instagram photos and videos