That’s the Spirit!

It’s late. You’re gathered with your friends on the living room floor, or maybe wrapped in sleeping bags around a campfire. One person in the group offers up a scary story or puts a flashlight under their chin to really creep everyone out. After their story is over, no one’s sleeping tonight. What you may not know is that gatherings like these have deep historical roots in our country.

Spooky stories abound at the Archives. Just ask a few of the long-serving guards in the historic Washington, D.C., building who can attest that the stacks are haunted. This is not dissimilar from a well-documented tale of a “demon cat” that has roamed Washington, D.C., since the Civil War.

This week, we’re delving into some spirited Archives records that may convince you that you’ve seen a ghost, or is it all just an illusion? Find out.

👻 BOO! 👻

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Knock Knock

Spiritualism is a religious movement that embraces the belief that consciousness persists after death and that the dead can communicate with the living. Spiritualism has existed since the beginning of human existence, but in the United States, it first manifested as a movement in upstate New York in the 1840s, the same area where the Second Great Awakening, a Protestant revival movement, arose in the early part of the 19th century. Several religious movements, including Mormonism, dispensationalism and Millerism, originated from the same area of the country. Spiritualism was not an organized religion, but rather a general belief in the existence of an afterlife from which the inhabitants could contact those who were still living on Earth. However, because most spiritualists believed that people would only contact the deceased through the interventions of mediums, the practice was particularly susceptible to fraud. Mediums usually communicated with spirits either via paranormal phenomena like table tapping or moving objects or by going into trances during which the spirits spoke through them.

In the United States, on March 31, 1848, the Fox sisters, Kate and Margaretta, of Hydesville, New York, announced that they had been contacted by the spirit of a peddler who claimed to have been murdered in their home and who communicated with them by rapping on the walls. Their claims caused a sensation in the small community, and the sisters, who were about 11 and 13, respectively, were sent away to Rochester. A Quaker couple, Amy and Isaac Post, took them in, and became convinced that the girls’ claims were true. The Posts were considered quite radical, being advocates of abolition, women’s suffrage and temperance, and they rapidly introduced the Fox sisters to like-minded individuals. Consequently, the spiritualist movement became fused with these social beliefs.

Late in life, in 1888, Margaretta Fox admitted that she and her sisters had made up the story of the murdered peddler and explained at great length how they had faked the rapping by which the spirit communicated with them. Her admissions caused an uproar in the spiritualist movement, and when she tried to recant them a year later, she was met with great disgust.

Prior to the American Civil War, several trance lecturers through whom spirits supposedly spoke were prominent in the spiritualist community. They included Cora L. V. Scott, Achsa W. Sprague and Paschal Beverly Randolph. When the war began and soldiers began dying in great numbers, more people were attracted to the spiritualist movement as they sought to contact their dead loved ones. A similar phenomenon occurred during and after World War I, especially in the United Kingdom. Spiritualism saw a rekindling during the 1970s, when the New Age movement sparked interest in “channeling” the spirits of past individuals and even extraterrestrials.

The spiritualism movement met opposition everywhere, especially from religious leaders, and most especially from the Catholic church. It was often associated with witchcraft, even though its practitioners disavowed that association.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

Is Anyone There?

Mary Todd Lincoln

by Mathew Brady

National Archives Identifier: 529952

The wife of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, Mary Todd Lincoln suffered one terrible loss after another throughout her life. Her mother died when Mary was six. She married Abraham Lincoln in 1842, and they had four sons, only one of whom, Robert Todd Lincoln, the eldest, survived to adulthood. Their second son, Eddie, died in 1850 at the age of four of tuberculosis. While Lincoln was president, their third son, Willie, died of typhoid fever.

In her grief, Mary began to practice spiritualism. Soon after Willie died, she met the Lauries, a group of mediums based in Georgetown, who helped her by holding séances to contact Willie. Mary soon began holding séances in the Red Room of the White House, some of which her husband attended.

White House Red Room

National Archives Identifier: 7498513

Mary Todd Lincoln was convinced that Willie contacted her during the séances, and the experiences gave her great comfort. She told a friend that Willie visited her every night and sometimes brought his brother Eddie with him.

On April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth shot President Lincoln in the presidential booth at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., with Mary looking on. In 1871, the Lincolns’ fourth son, Thomas, nicknamed “Tad,” died at the age of 18. Not surprisingly, Mary Todd Lincoln suffered from profound grief and depression. She consulted a spiritualist photographer, William H. Mumler, in 1872, who produced a portrait of her with what appears to be the ghost of Abraham Lincoln standing behind her. Mumler’s works have since been proven to be hoaxes.

Lincoln Room during White House renovation

National Archives Identifier: 6993192

Convinced that his mother’s behavior was dangerously erratic, Robert Todd Lincoln persuaded a court to institutionalize Mary Todd Lincoln in 1875. She was briefly committed to Bellevue Place, a private sanatorium in Batavia, Illinois, but widespread publicity and the resulting public disapproval resulted in her release into her sister’s custody in 1876. Now estranged from Robert Todd Lincoln, she then went to Europe for four years and returned to Springfield, Illinois, to live with her sister. She died in 1882 and was buried next to her husband.

Just an Illusion

Harry Houdini draft card

National Archives Identifier: 641795

Harry Houdini, the most famous illusionist and escape artist of his generation, had absolutely no patience with spiritualists, all of whom he considered frauds. Born Erik Weisz to a Jewish family in Budapest, Hungary, in 1874, he, his six siblings and his parents immigrated to the United States in 1878. The family settled briefly in Wisconsin and then moved to New York City, where Erik’s name was Americanized to “Erich Weiss.” He became a professional magician in 1891, calling himself “Harry Houdini” after the French magician Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, but it was not until he began performing intricate and dangerous escape acts that he catapulted to fame, becoming, by the turn of the century, one of the highest-paid entertainers in the world.

Houdini began exposing spiritualists as frauds in the 1920s. Because he was well versed in tricks and sleight of hand, he was adept at figuring out how the spiritualists of his day pulled the wool over the public’s eyes. He sat on a committee of Scientific American magazine that put up a cash prize to any spiritualist who could prove their supernatural abilities, but none was ever able to do so, and the prize went unclaimed.

Divers’ suit patent invented by Houdini

National Archives Identifier: 167819289

Divers’ suit patent invented by Houdini

National Archives Identifier: 135816123

Houdini exposed George Valiantine of Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania, the medium Mina Crandon, known as “Margery,” Joaquín Argamasilla, known as the “Spaniard with X-ray Eyes,” and the Italian medium Nino Pecoraro as frauds. He described his exploits in his book “A Magician among the Spirits,” which he co-wrote with C. M. Eddy, Jr. An unfortunate casualty of his zeal for debunking spiritualists’ claims was his friendship with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who was convinced Houdini used paranormal abilities to complete his stunts. Their disagreement turned them from friends to bitter enemies.

When he was dying, Houdini told his wife Bess that if the dead could communicate with the living, he would send her a message, “Rosabelle believe.” He passed on Halloween, October 31, 1926, and for 10 years, Bess held a séance on the anniversary of his death. She never received a message from her husband. On that night, she put out the candle that she had kept burning beside his photograph since the night of his death. Bess is reported to have said in 1943, “Ten years is long enough to wait for any man.”

Let’s Talk

Patent US446054A

Elijah J. Bond

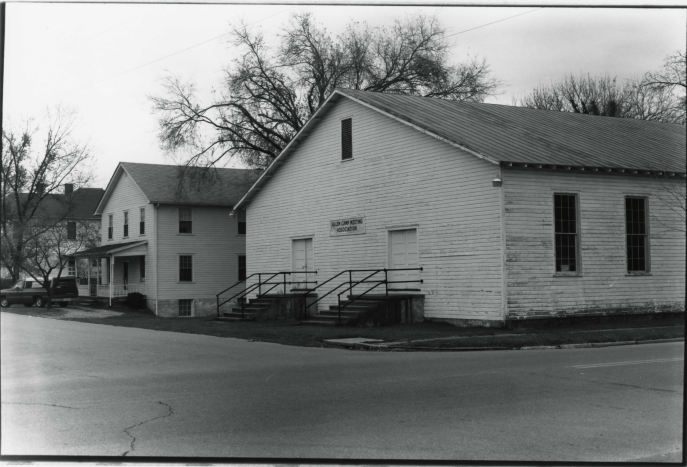

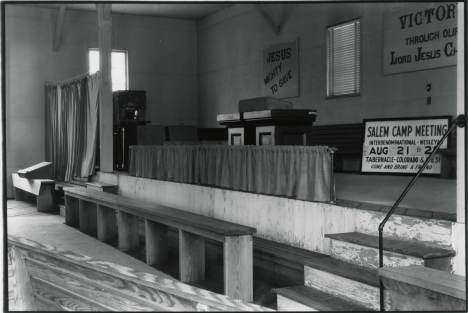

Talking boards were a common tool of spiritualists in the United States in the late 19th century, who used them to contact the dead. In 1890, Charles Kennard and four other investors created the Kennard Novelty Company in Baltimore, Maryland, for the express purpose of manufacturing and selling talking boards to the public. Stories about how the board got its name vary widely (and wildly), but in the end, the makers settled on “Ouija.” They were awarded a patent for it on February 10, 1891.

The Ouija board has had a checkered history, having been sold as both a parlor game for families and as a way to contact those who have passed. It has been embraced by believers and debunked as pseudoscience by skeptics. Perhaps nothing has so colored its reputation as the film “The Exorcist,” in which the innocent child Regan plays with a Ouija board and winds up possessed by a demon.

Charles W. Kennard’s “Talking Board”

Source: National Archives at Kansas City

Eternal Construction

Sarah Lockwood Pardee was born to Leonard Pardee and his wife Sarah Burns in New Haven, Connecticut in 1839, where in 1862, she married William Wirt Winchester, the heir to the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. The couple had one child, a daughter, Annie Pardee Winchester, who died about a month after her birth in 1864. Then in 1881, Sarah lost her father-in-law, her mother and her husband.

Inconsolable, Sarah consulted a medium, who told her all these deaths were the revenge of the victims whose lives had been lost to the firearms the Winchesters had manufactured and were still making. The medium told Sarah that she herself was cursed, and that if she wished to stay alive, she had to move west and build a house for the spirits, constantly, without ceasing, day and night.

And so she did. The Winchester Mystery House at 525 S. Winchester Boulevard in San Jose, California, stands on the southeast third of an 18.4 acre tract of land. It began life as an eight-room farmhouse, but at its largest, the house had about 500 rooms. Sarah built, remodeled and tore down continuously and with no particular plan, abandoning projects that lost her favor, so the house has staircases that lead nowhere, rooms that run maze-like from one to another and walled-off interior doors and windows.

The 1906 earthquake severely damaged the house, destroying one entire wing and collapsing most of the chimneys and a seven-story tower. Although Sarah resumed construction, she was less ambitious in her later years. By the time she died in 1922, the building, which is now on the National Register of Historic Places, had only 160 rooms.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above