Take This Job And…

Whether it’s Johnny Paycheck’s anthem or Dolly Parton’s famed “Workin’ 9 to 5,” the eight-hour workday with breaks, weekends, days off, and safe workplace standards are no accident.

Throughout our nation’s history, workers and community leaders have organized to demand humane treatment on the job. As the Industrial Revolution revved up and the economy expanded, workers (both adults and children) were often put in difficult and dangerous work situations. Factories with locked doors, underground in mines without breaks, and twelve-hour days working six days a week were not uncommon. Even though there is much discussion over changes to office-based workplaces now in the aftermath of the COVID pandemic, many workers continued to grind it out throughout the health crisis. Labor Day is the nation’s holiday to celebrate advancements in the workplace. This week, we add our gratitude to all of the individuals and organizations that fought for decades to make our lunch break happen with labor stories from the Archives.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Getting Organized

Unions have been in the news a lot lately as workers who a few years ago would seemingly have never thought about it are now voting to unionize. In mid-June, a majority of employees at the Apple Store in Towson, Maryland, voted to join the Machinists Union. As of Wednesday, August 3, employees at 209 Starbucks stores have voted to unionize, according to the National Labor Relations Board. Unions are also being formed at Trader Joe’s, Activision Blizzard, a Google Fiber contractor, Kickstarter, and REI. Many factors are contributing to this situation, which appears to be reversing the trend of declining union membership that has been persisting since Ronald Reagan became President in 1980.

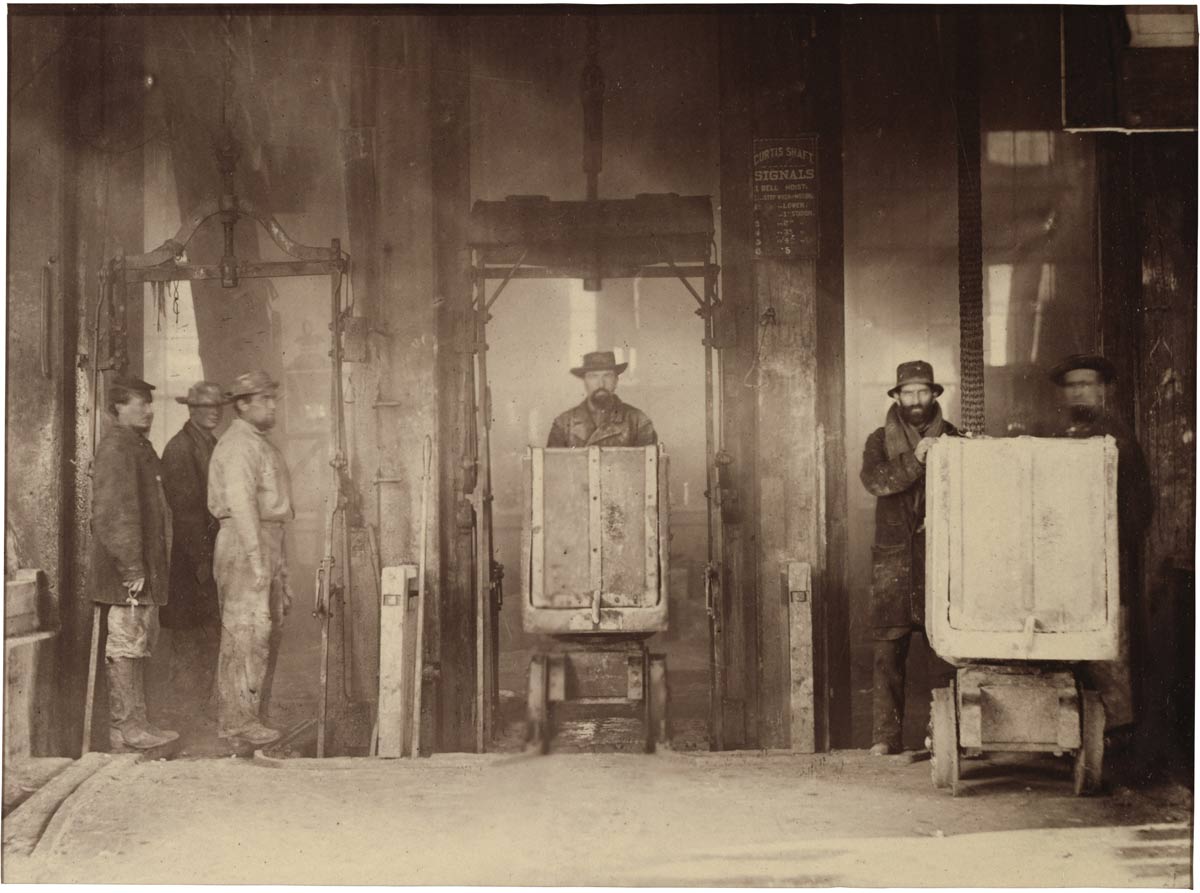

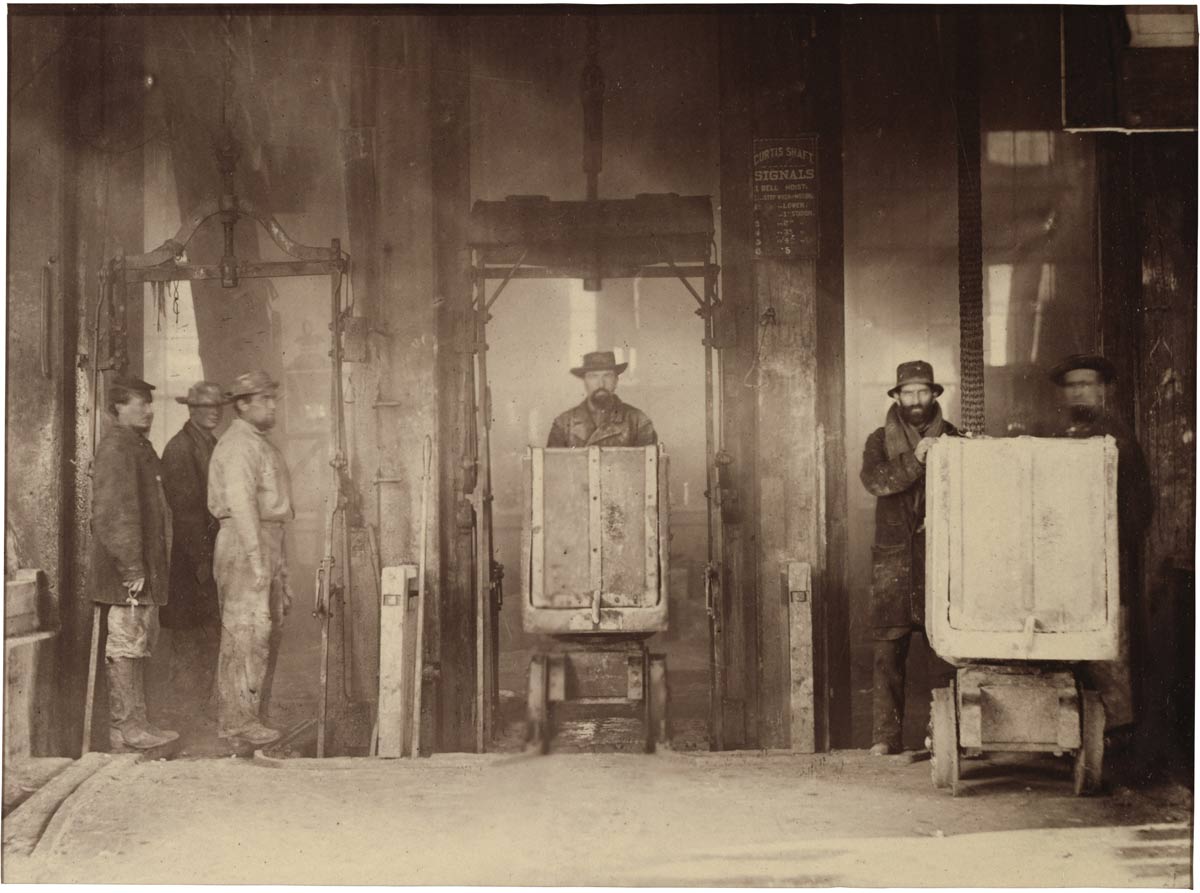

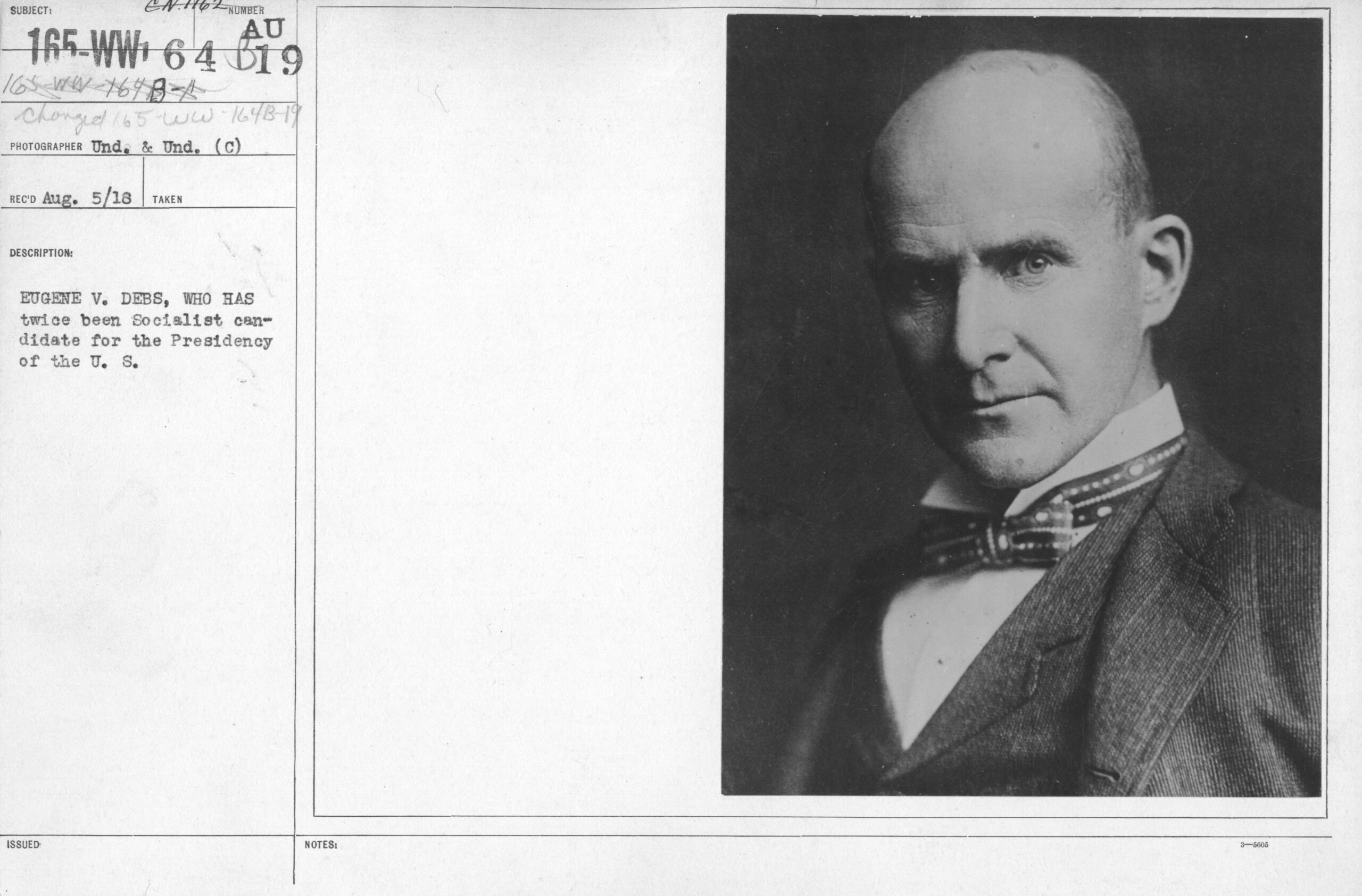

In the United States, labor unions started being formed after the end of the Civil War. In 1905, William Hayward, a former hard-rock miner, gave a speech at Brand’s Hall in Chicago to a group of more than 200 socialists and trade unionists, including Daniel De Leon, the leader of the Socialist Labor Party, Eugene Debs, the leader of the American Socialist Party, and Mother Jones, who crusaded for children’s and miner’s rights. Out of that meeting arose the predominant labor union of the early twentieth century, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), commonly called the “Wobblies.” The IWW was an unapologetically socialist organization that gave capitalism no quarter. “The Industrial Workers are organized not to conciliate but to fight the capitalist class,” said Eugene Debs. “The capitalists own the tools they do not use, and the workers use the tools they do not own.”

Then and now, organizers are the front-line operatives of any union. They are the face of the organization, the ones who communicate the values of the union to potential members and encourage them to join it. Franklin Henry Little worked as a union organizer for the IWW from 1905 until 1917, when he was lynched in Butte, Montana. Details about his early years are sketchy, but Little was believed to have been born in Oklahoma Territory in 1879. He is reported to have been half Cherokee and half Quaker. In his early twenties, he followed his brother to California and became a miner. After a short stint of mining in Bisbee, Arizona, Little joined the Western Federation of Miners as an organizer. He joined the IWW in 1905.

From the start, Little’s tenure with the IWW was harrowing. His techniques were pioneering—he used passive resistance methods that were later adopted by the Freedom Riders in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, and very often, he employed free speech campaigns as the thin edge of the wedge to drive his organizing campaigns. His first effort was in Missoula, Montana, where he helped organize lumber workers. Then he participated in another free speech fight in Spokane, Washington, where he read the Declaration of Independence on a street corner and was thrown in jail for thirty days in retaliation. Frank Little went on to organize workers in Fresno, California, the San Joaquin Valley in California, Duluth, Minnesota, and Superior, Minnesota. His enemies, who hated and feared him, quite regularly kidnapped him, beat him up, held him at gunpoint, and threatened to hang him.

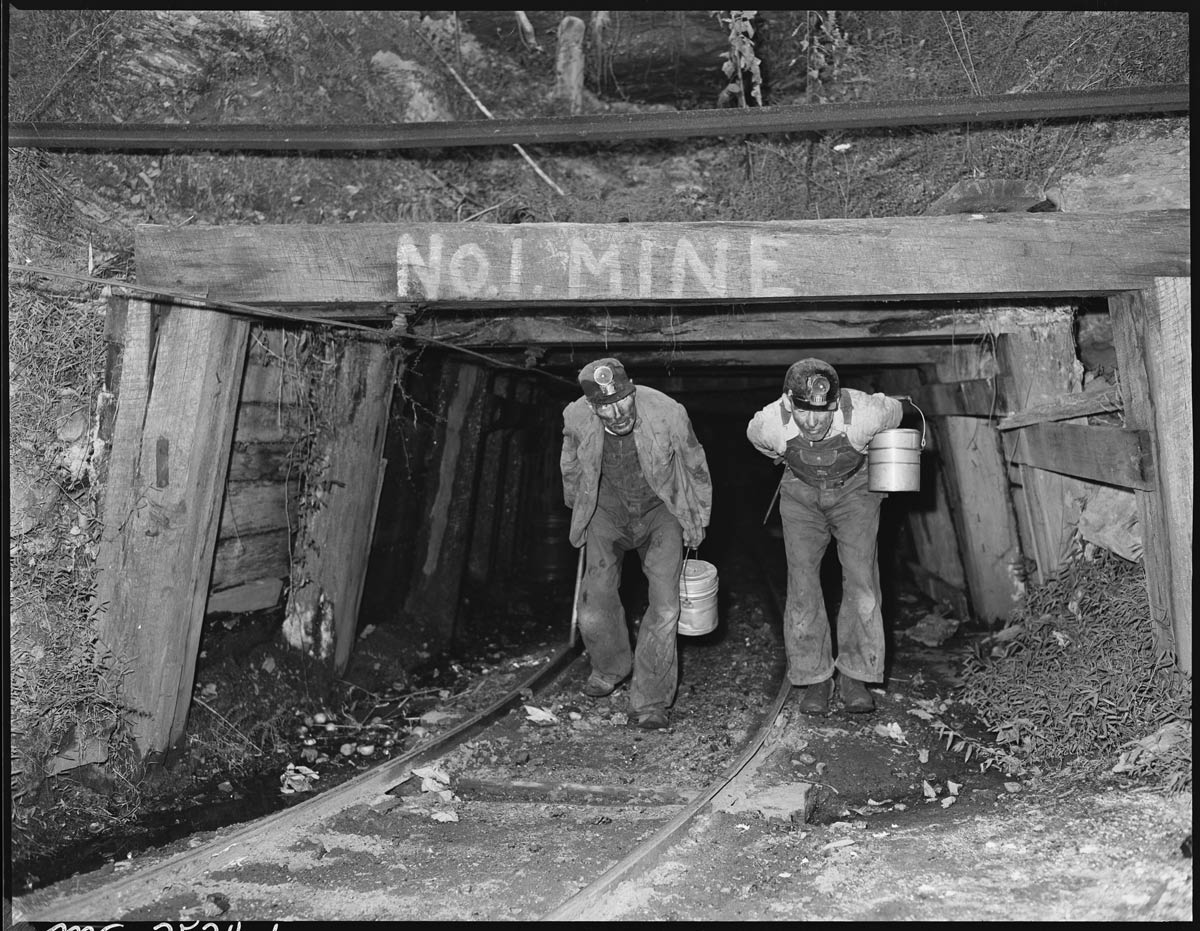

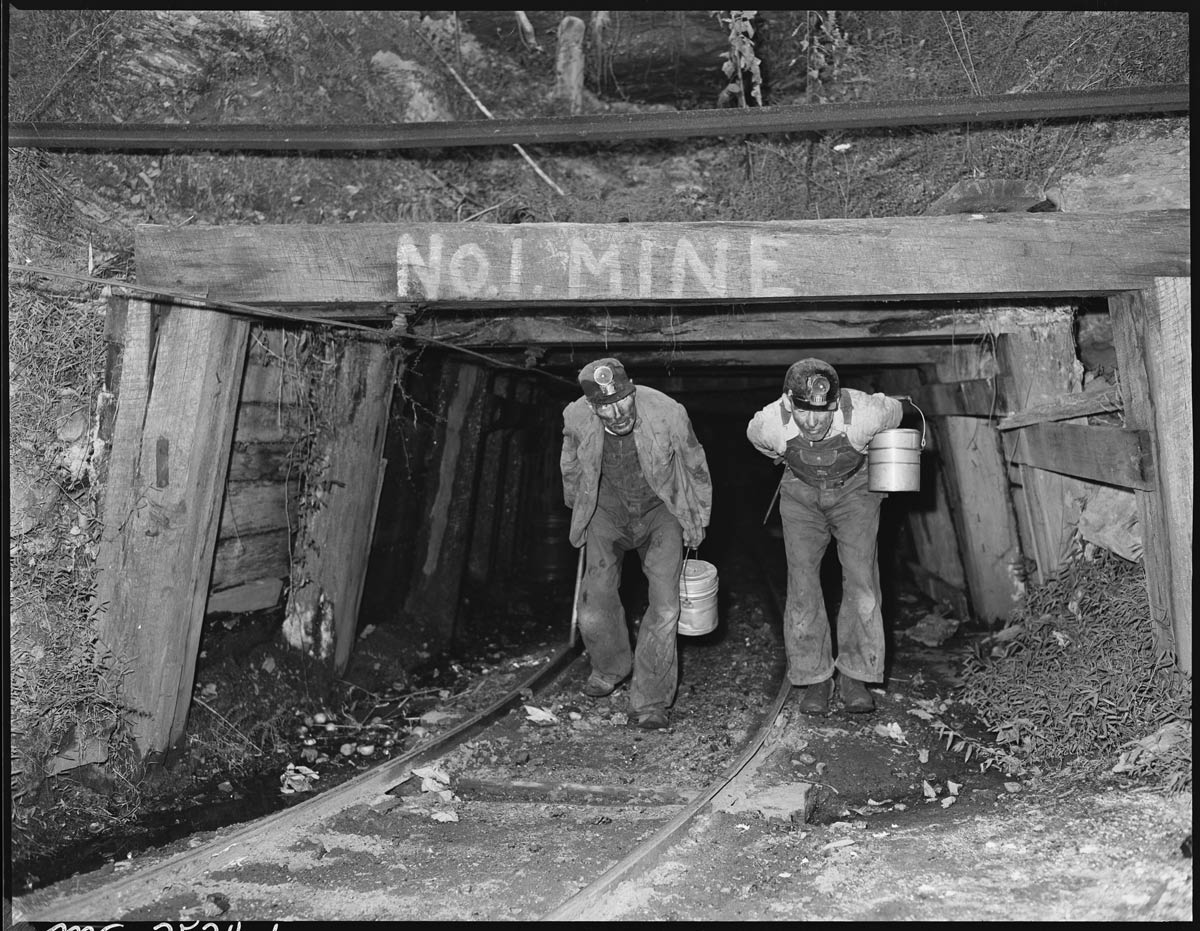

In 1914, Little was elected to the General Executive Board of the International Workers of the World. He was also opposed to war, a stance that got him into trouble with some of the leaders of the IWW when World War I began. The editor of the IWW’s newspaper, Solidarity, Ralph Chaplin, insisted that the union had to support the war or face retaliation by the government, which could destroy it. Little and other board members argued that the union needed to gain more members before it would be powerful enough to oppose the war.On June 8, 1917, 168 miners had died when a fire started in the Granite Mountain shaft of the Spectacular Mine, owned by the North Butte Mining Company, in Butte, Montana. The surviving mine workers then formed a union and went on strike. Hampered by a broken ankle and persistent injuries from the beatings he’d endured, Frank Little still went to Butte to organize the copper miners and lead a strike against the Anaconda Mining Company. He arrived on July 18, 1917, and immediately organized picket lines, encouraged other trade workers to join the strike, and spoke out against the war.

On August 1, while he was asleep in a boarding house in Butte, Frank Little was abducted by six masked men who hustled him into a car and drove away with him. Then they tied him to the rear bumper of the car and dragged him behind it for several blocks to the Milwaukee Bridge, where they hanged him from a railroad trestle. No one was ever prosecuted for Little’s murder.

“Frank Little is an American hero, not for the great things he accomplished in his lifetime, but because he remained true to his revolutionary principles until the day he died,” states his biography on the IWW website. His funeral was the largest ever in the history of Butte—an estimated 10,000 people attended it. His grave marker in Mountain View Cemetery reads, “Slain by capitalist interests for organizing and inspiring his fellow men.”

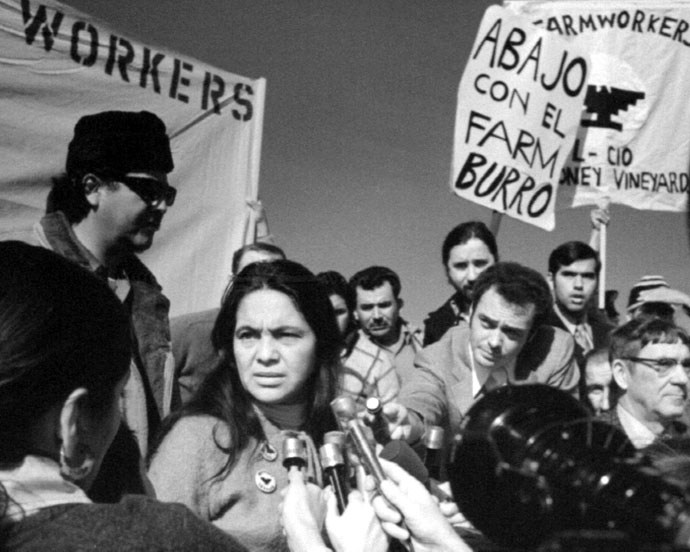

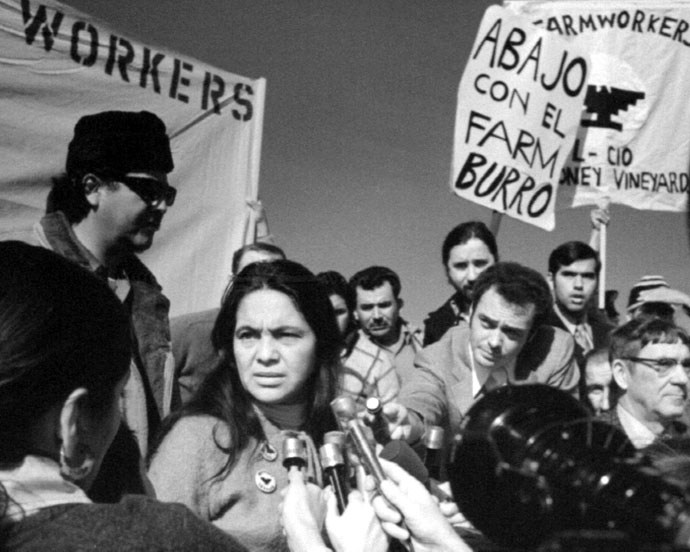

Dolores Clara Fernández Huerta began her union career in 1955, when she cofounded the Stockton, California, chapter of the Community Service Organization with Fred Ross. The organization aimed to improve economic conditions for migrant farm workers, and Ross recognized that Huerta, who had grown up in the farmworker community of Stockton, had graduated from college, had taught elementary school, and who spoke both Spanish and English, was uniquely suited for communicating the organization’s message by going door to door.

From there, Huerta went on to cofound the Agricultural Workers Association in 1960, and then in 1962, she cofounded the National Farm Workers Association with César Chávez. That organization eventually became the United Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee. For the next several years, she worked for organizations that aimed to improve the lives of farmworkers, including their wages, working conditions, living situations, and the educational opportunities of their children.

By 1965, the United Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee had merged with the National Farm Workers Association to become the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee (UFW). In September 1965, Filipino grape pickers in Delano, California, went on strike, demanding better wages, and Huerta spearheaded the UFW’s actions in support of their strike, which included boycotts of companies that used Delano grapes. In the end, in 1970, the strike and the boycotts forced the table grape producers to sign a collective bargaining agreement with the United Farm Workers.

Huerta’s successes have not come without costs. She has been arrested many times for participating in peaceful demonstrations. In September 1988, she was savagely beaten by a policeman in front of the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco during a peaceful protest of the policies of presidential candidate George H. W. Bush. She was taken to the emergency room, where she had surgery to remove her spleen. She received a financial settlement from the city of San Francisco for the beating, which she donated to help farm workers.

She has also been the victim of routine racist and sexist criticism for her actions throughout her life. In 2002, Huerta founded the Dolores Huerta Foundation, which creates leadership opportunities for community organizing, leadership development, civic engagement, and policy advocacy. She received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama on May 29, 2012.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

18 Minutes

Firefighters at the factory

National Archives Identifier: 6040087

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory was located on the eighth, ninth, and tenth floors of the Asch Building (later renamed the Brown Building) in Greenwich Village, on the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place in New York City. Approximately 600 workers, mostly young Italian and Jewish immigrant women, sewed women’s blouses, then called “shirtwaists,” in the factory, earning $7 to $12 each week for fifty hours of labor (the equivalent of $4.03 to $6.91 an hour in 2022 dollars).

Broken fire escape – NAI: 6040085

National Archives Identifier: 6040085

The factory was owned by Max Blanck and Isaac Harris. On Saturday, March 25, 1911, a fire started in a scrap bin under one of the cutters’ tables on the eighth floor. When an attempt to extinguish the fire failed because the fire hose was rotten, the workers started trying to escape by the elevator, but it would only hold twelve passengers at a time. The operator made four trips up and down, but then the fire and heat disabled the elevator. The women who had been waiting for it jumped down the elevator shaft to their deaths.

The young women and girls who had tried to escape down the stairwells discovered that the doors at the bottom were locked, which was common practice at the time to prevent workers from stealing and from taking unauthorized breaks. They burned to death at the bottom of the stairwells.

The owners and some of the workers went up to the roof and then crossed over to safety on the roofs of adjacent buildings. Workers who couldn’t escape to the roof or get to the stairwells or the elevator started jumping out the windows. Firefighters arriving on the scene couldn’t help them because their ladders only reached seven stories high.

Victims on the sidewalk

National Archives Identifier: 6040083

The whole tragedy lasted only eighteen minutes, from start to finish. One hundred and forty-six workers died. The oldest identified victim was forty-three, and the two youngest were fourteen.

Building interior after the fire

National Archives Identifier: 6040089

Owners Blanck and Harris had been suspected of setting fires in their Diamond Waist Company factory twice before and in the Triangle factory twice prior to the 1911 disaster to collect on their fire insurance—an unethical but common practice at the beginning of the twentieth century. Arson was ruled out in the case of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, but Blanck and Harris had refused to install sprinkler systems and reliable fire escapes and stairwells in the buildings. Their negligence unmistakably contributed to the deaths and injuries that day. Nevertheless, a grand jury failed to indict them for manslaughter. Blanck and Harris ended up paying the families of the victims $75 each, while their insurance company paid them $400 for each death.

Mourners and demonstrators after the fire

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

All that said, the tragedy galvanized the labor movement in the United States and united it with progressive politicians and, ultimately, with the Democratic Party. The workers union organized a march down Fifth Avenue on April 5 that 80,000 people attended. Politicians in the city passed the Sullivan-Hoey Fire Prevention Law, which established the New York City Fire Prevention Bureau and required factory owners to install sprinkler systems in their buildings.

Sleeper Boycott

An Act making Labor Day a holiday

Source: AOTUS blog archives

If you were doing some cross-country traveling in the late 1800s, you may have found yourself in a Pullman Car. Perfected (but not invented) by George Pullman, these cars allowed for elaborate luxury railway travel, acting as a living room, dining room, and bedroom for parties of up to a dozen people. Offering limitless customization options, including the ability to install a marble fireplace in one of the cars, Pullman made his fortune by designing and shipping these cars all over the United States.

But luxury sleeper cars weren’t all that Pullman was known for; his business was one of the earliest to establish company towns, a community where employees both lived and worked. Pullman wasn’t just a name or a business—it was also an entire neighborhood in Chicago where workers lived in company housing, and both wages and rents were set by the Pullman company.

Eugene Debs, two-time socialist candidate for President

National Archives Identifier: 134982162

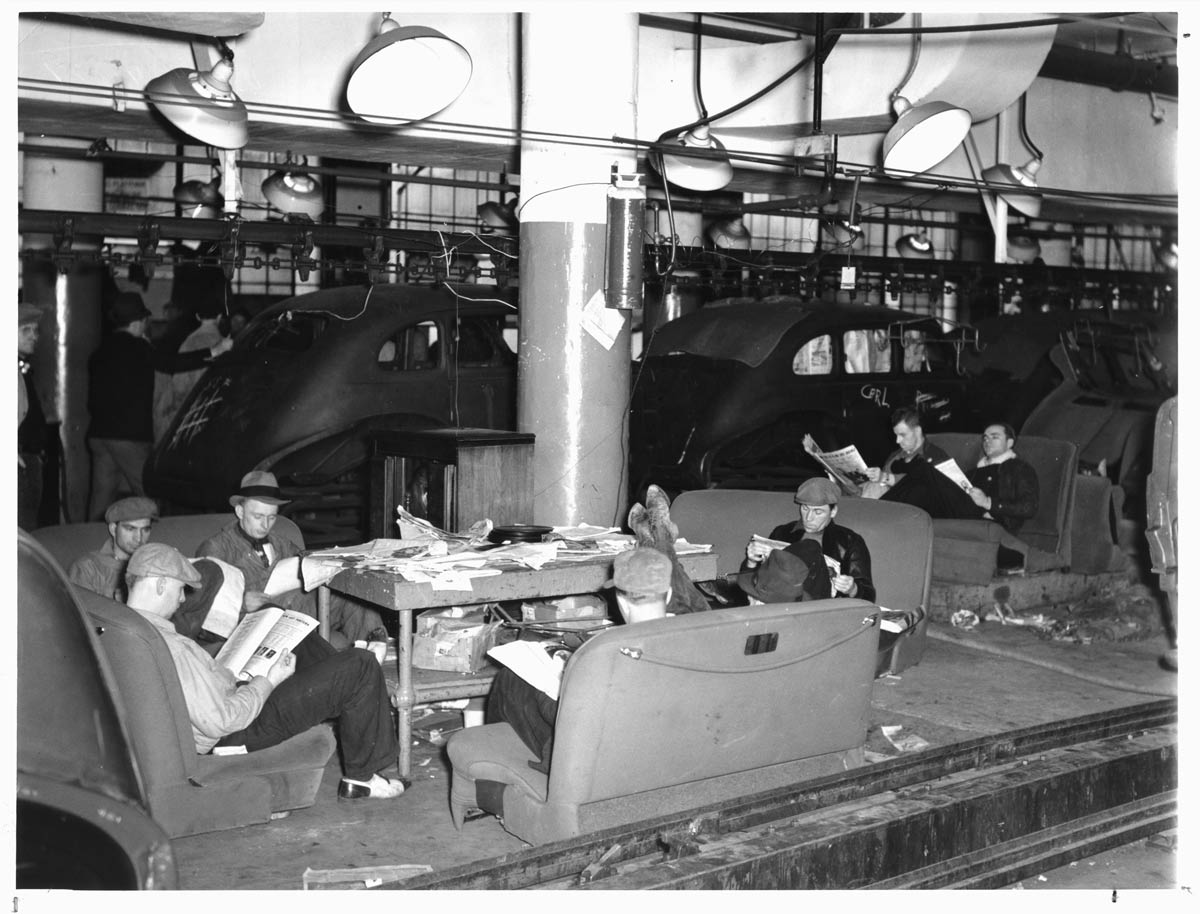

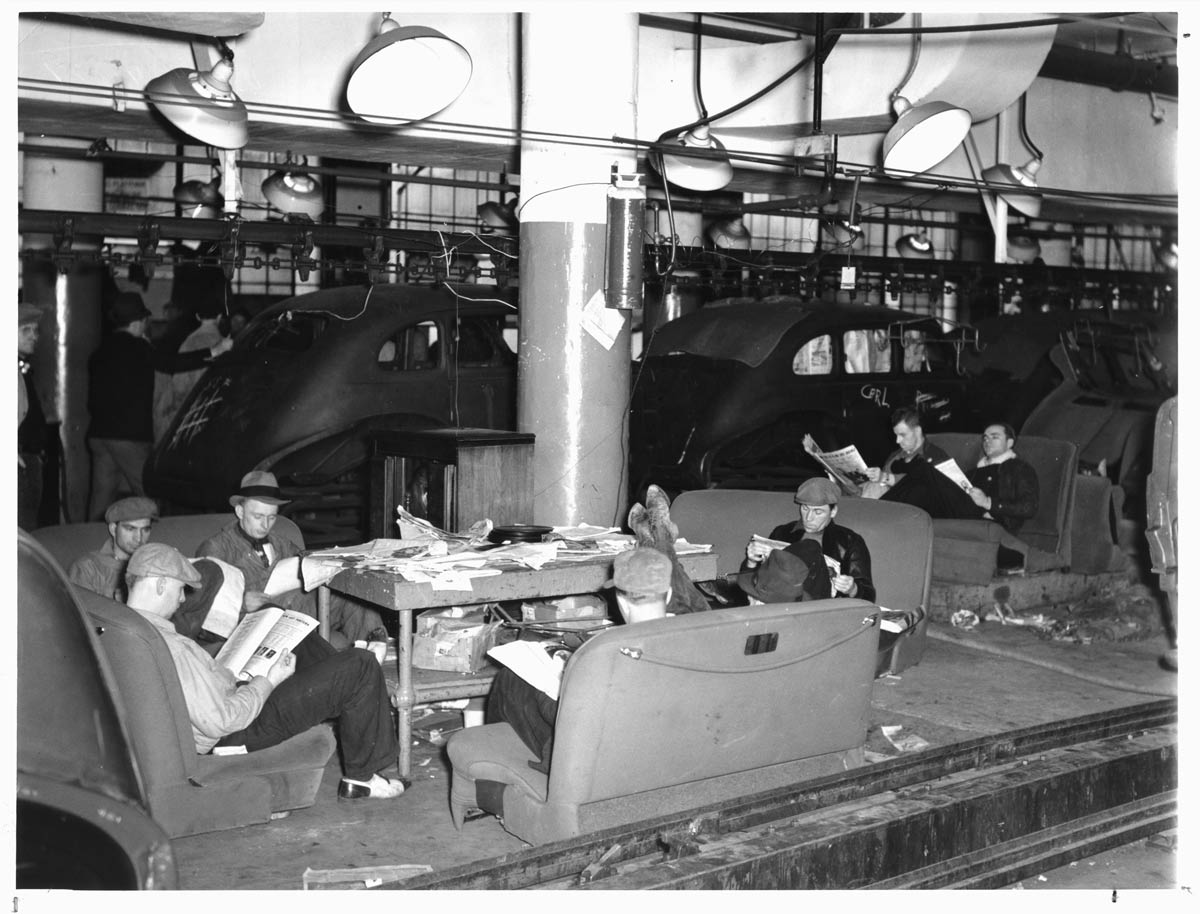

When an economic crisis known as The Panic of 1893 struck, luxury sleeper cars were one of the first expenses people cut back on, and orders and revenue dwindled. In response, the Pullman Company laid off workers and reduced wages, but it didn’t reduce rents in company housing. The remaining workers found themselves in untenable financial straits. Although they did not have a union, on May 11, 1894, more than 4,000 Pullman workers not only went on strike, but with the input of labor organizer Eugene Debs, they also organized a boycott against all trains that carried Pullman cars.

Read more about strikes in the U.S.

National Archives Identifier: 231768300

This brought rail travel to a grinding halt, harming the already sluggish economy. President Grover Cleveland tapped his attorney general, a former railroad lawyer, to oversee a federal response to the strike, which involved sending in the military. Already a powder keg, the arrival of troops caused the strike to turn into chaos. During clashes with the military, thirty strikers were killed and fifty-seven were wounded. Pullman cars were destroyed and burned, causing $80 million in damage.

Labor Day cartoon by Clifford Berryman

National Archives Identifier: 6010329

This sent shockwaves across the country, in which press and public opinion were generally negative. Even the labor movement itself was divided about the actual boycott, with union leaders like Samuel Gompers speaking out against it. The strikers, who were mostly underpaid immigrants, were cast as unpatriotic and dangerous. Nevertheless, Cleveland wanted to mitigate the damage caused by both the deaths and widespread coverage of the strike. That same year, he created a holiday to celebrate workers called “Labor Day.” In designating it the first Monday of September, he also looked to dilute the effect of May 1st or “May Day,” the more radical holiday celebrated by socialists and union organizers.

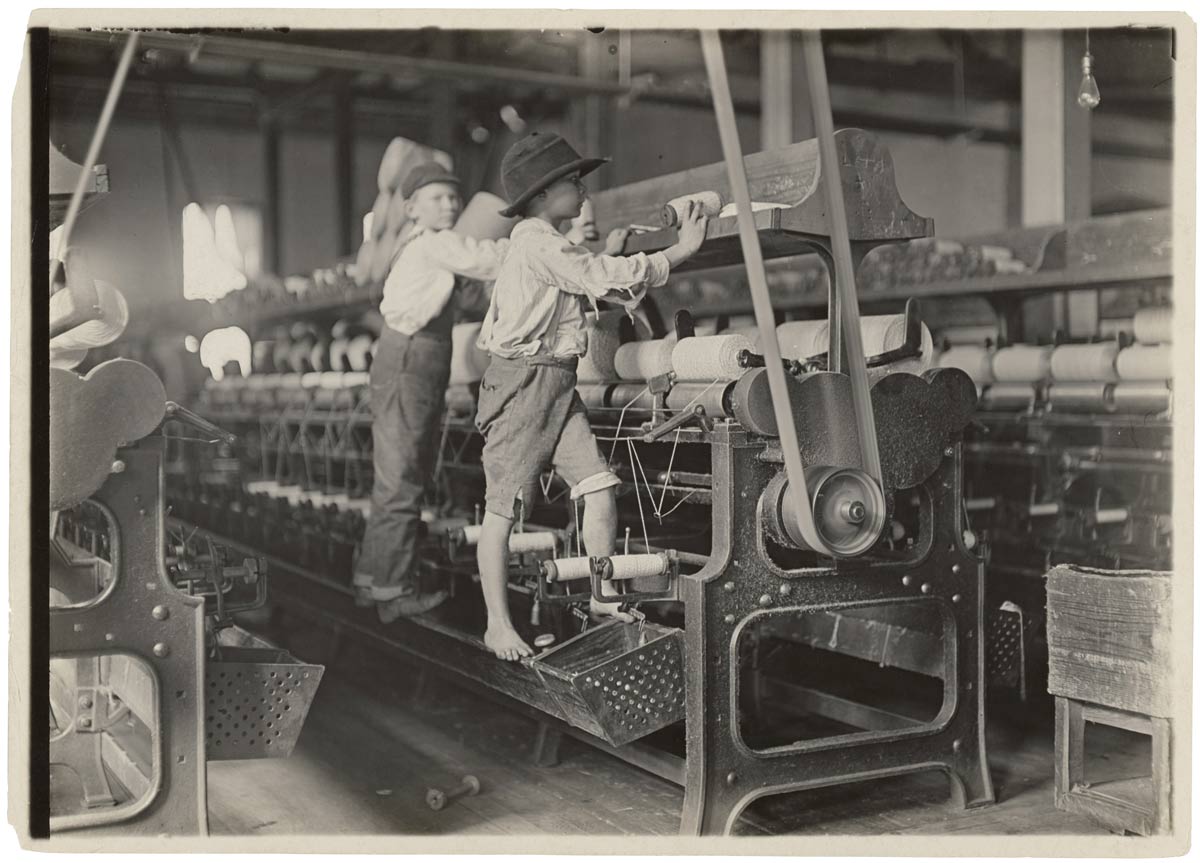

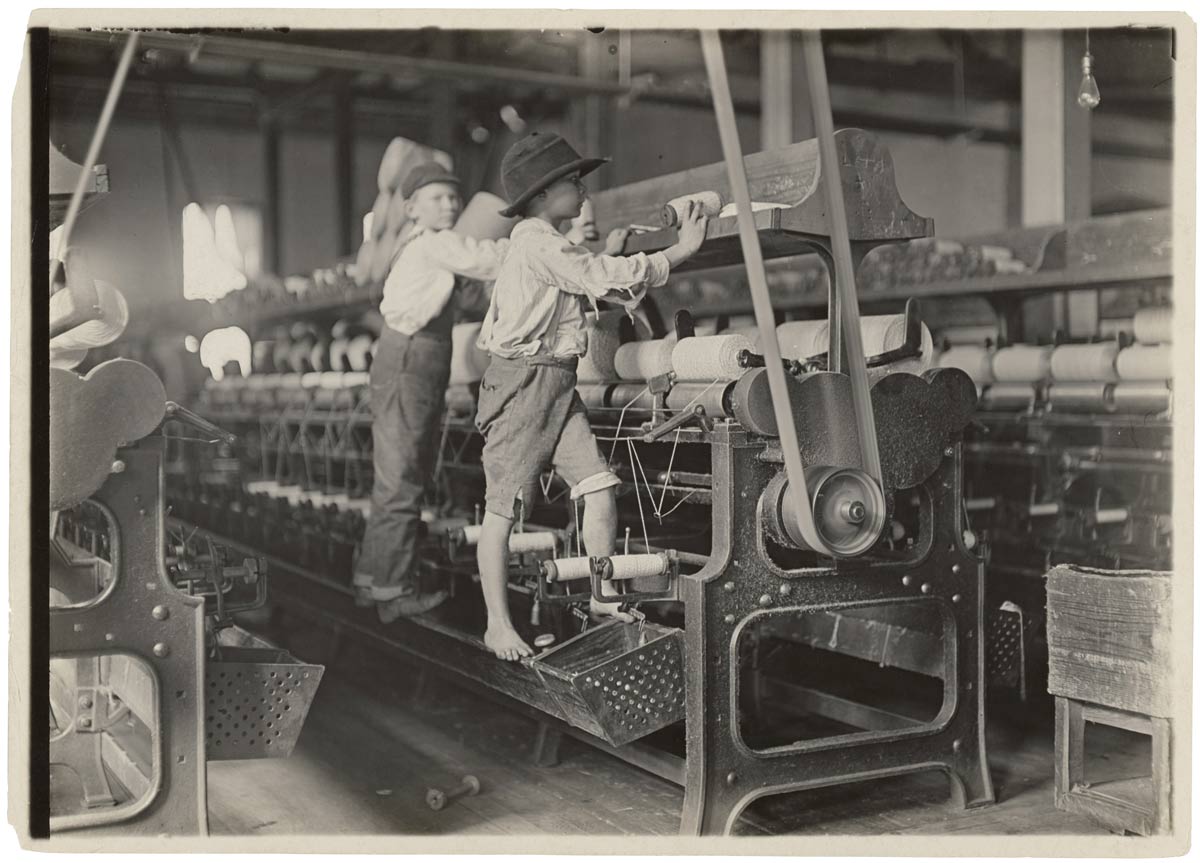

Dangers to Kids

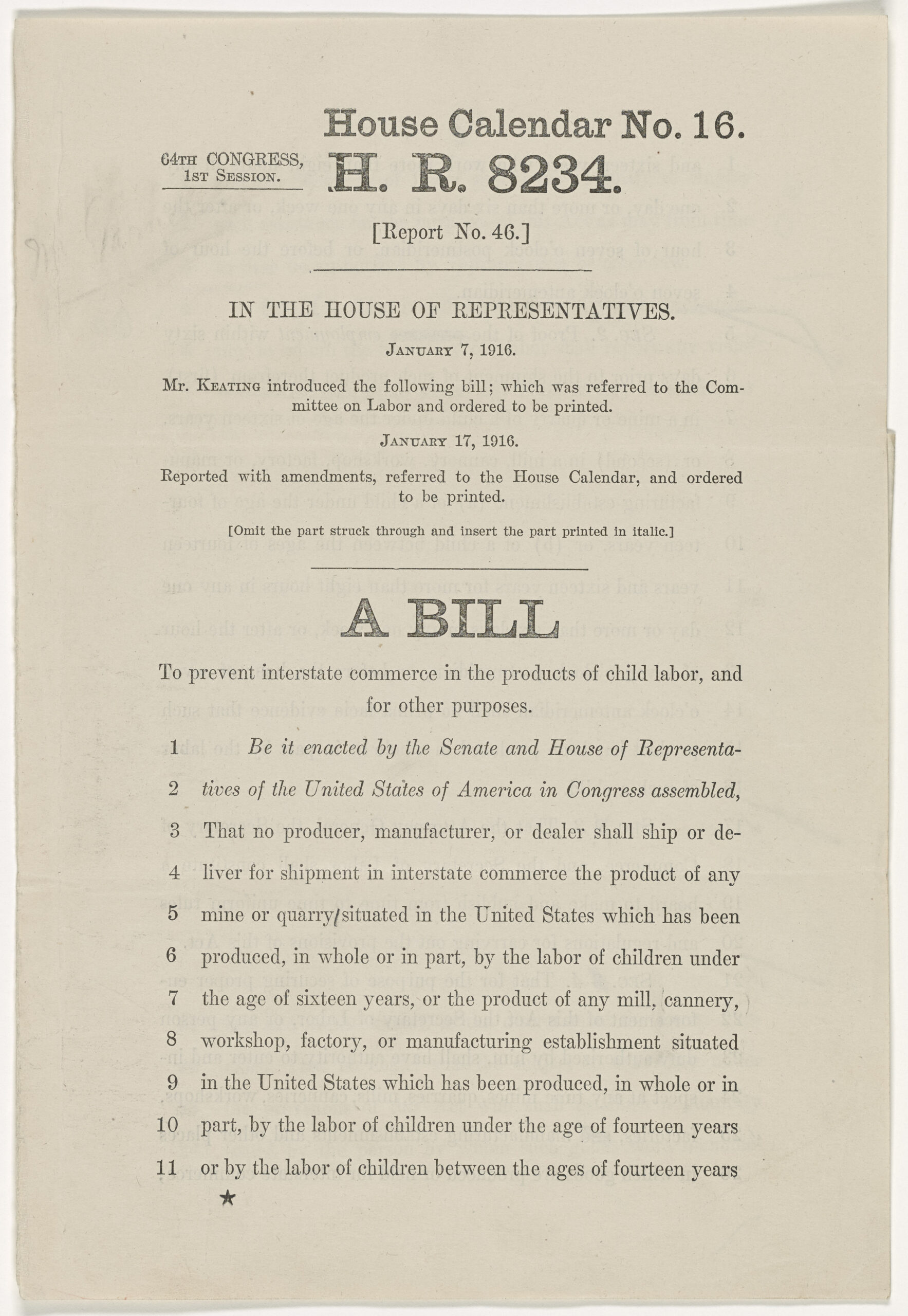

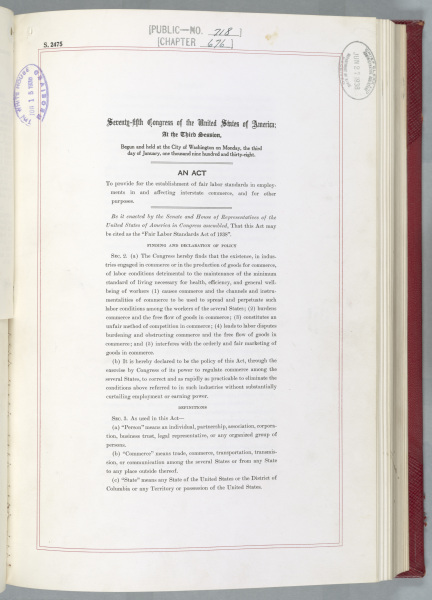

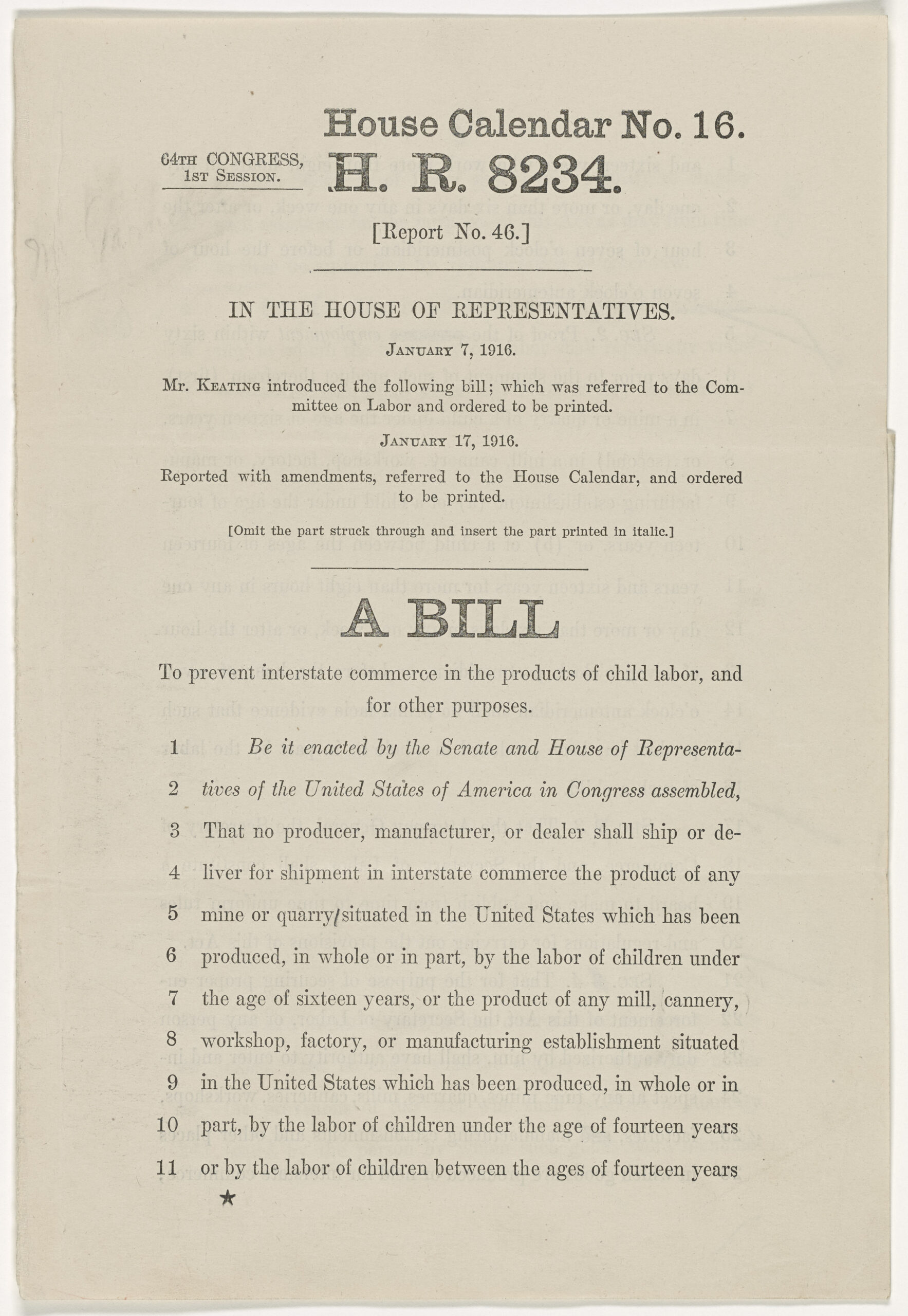

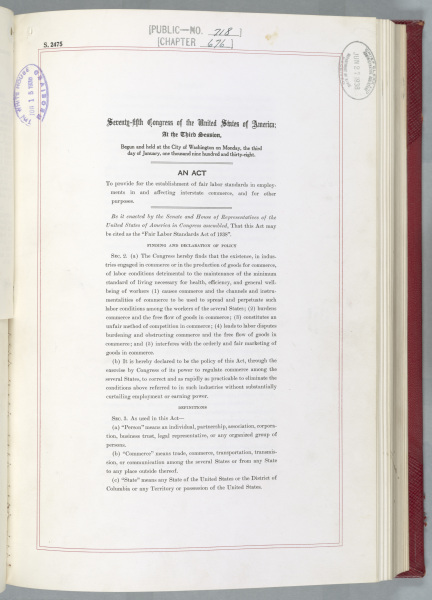

The first law Congress passed to ban child labor was the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act of 1916. Indiana Senator Albert J. Beveridge had written a proposal in 1906 that formed the basis of the Keating-Owen Act, which banned the sale of products from any facility that employed children under the age of sixteen at night or for more than eight hours during the day, from any factory, shop, or cannery that employed children under the age of fourteen, and from any mine that employed children under the age of sixteen.

Learn more about the Fair Labor Standards Act in the Records of Rights

Source: NARA’s Records of Rights Exhibit

Although Congress passed the law and President Woodrow Wilson signed it, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional on the grounds that it interfered with interstate commerce. It took several more tries and more than twenty years, but finally, in 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, and the Supreme Court agreed that it was constitutional in 1941, thereby outlawing child labor throughout the land.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

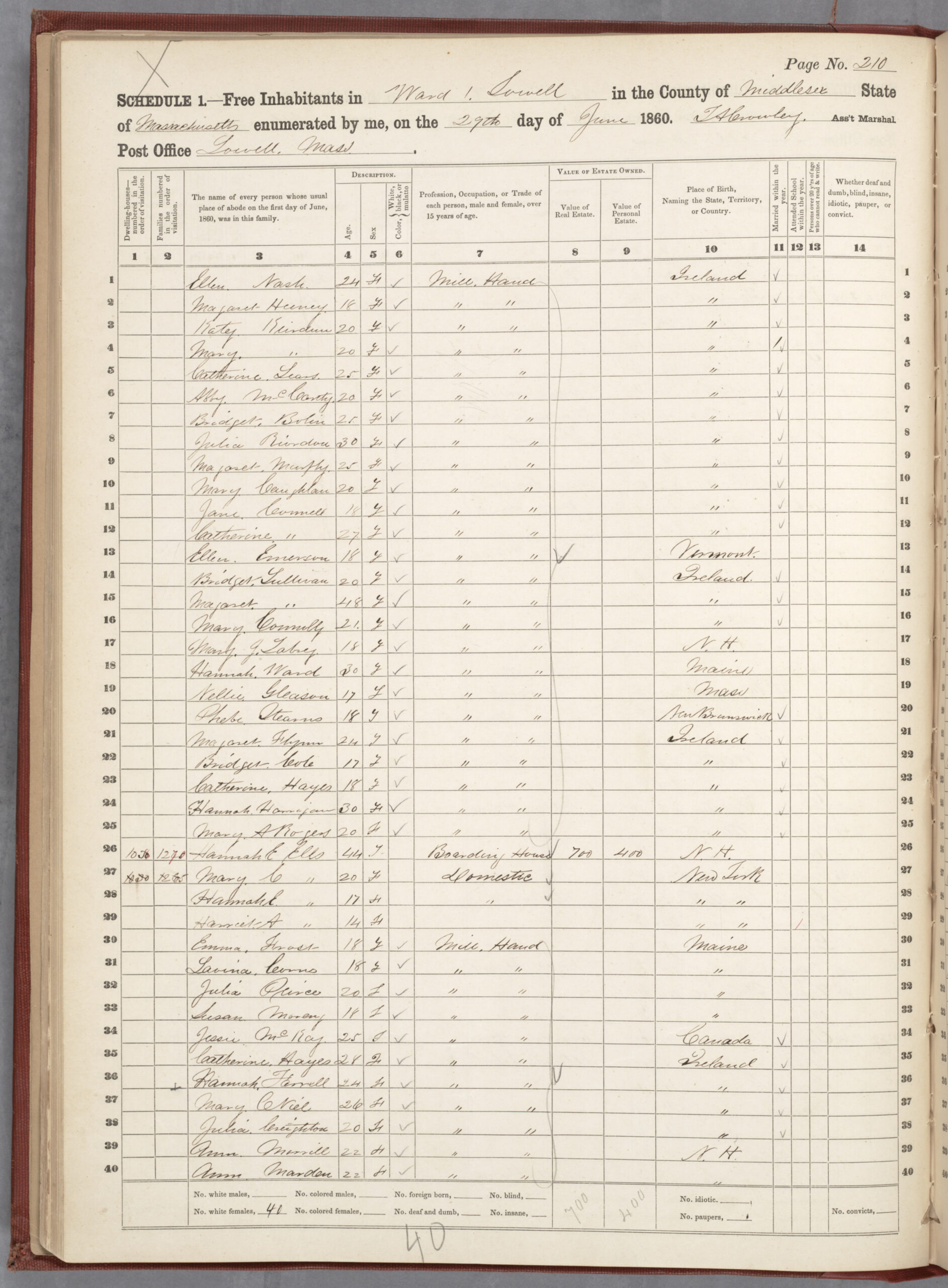

Mill Girls

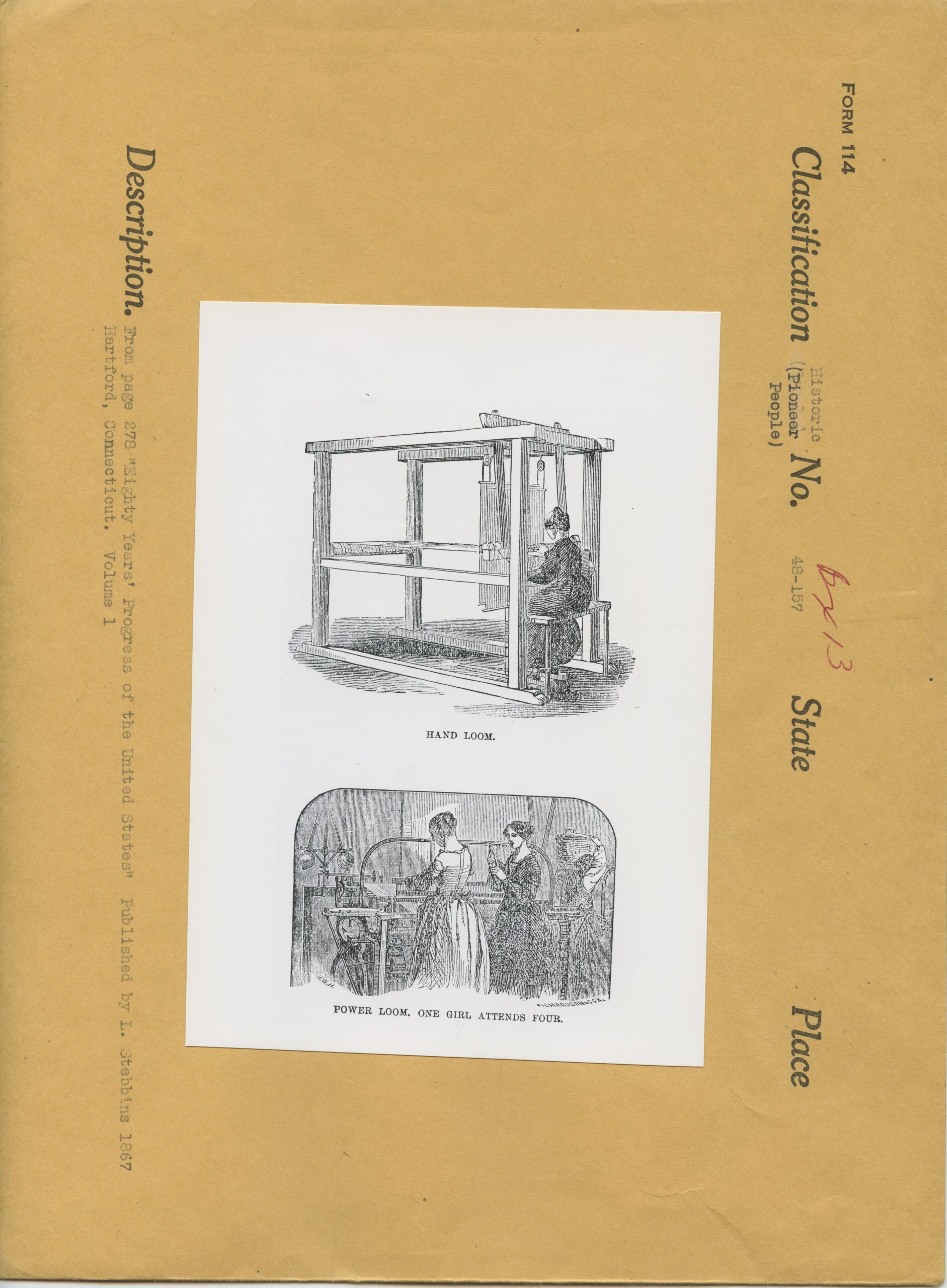

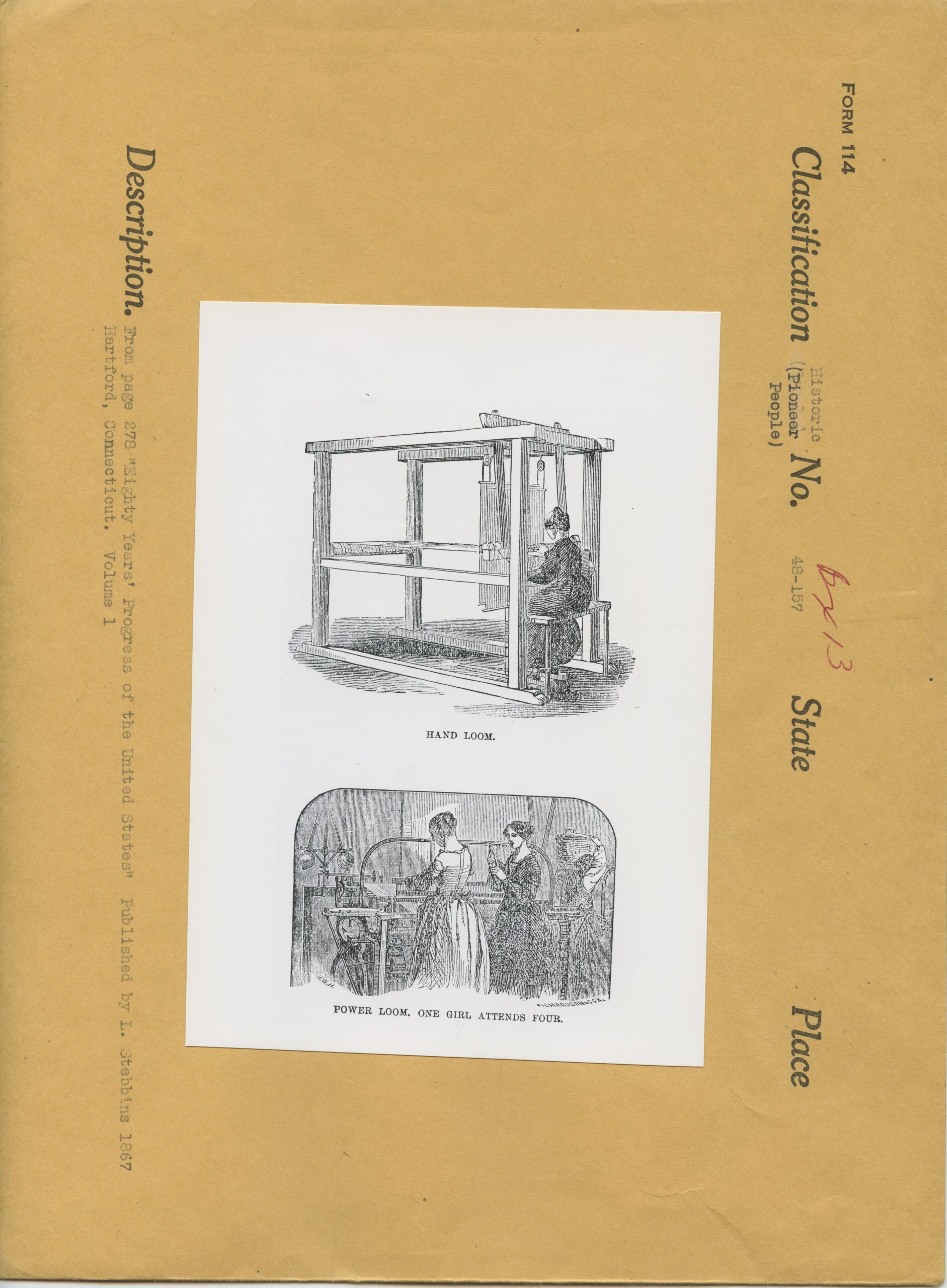

Francis Cabot Lowell was an American merchant who was born in Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1775. He graduated from Harvard University in 1793 and started trading in silks and tea from China and cotton fabrics from India.

In 1810, Lowell and his family took a trip to Britain, where he became interested in the spinning and weaving industries there. He visited textile mills and studied the machines, and he memorized how they all worked. By 1812, when war broke out between Great Britain and the United States and Lowell and his family returned to the U.S., he was ready to set his plan for a new textile empire in motion.

In 1814, Lowell, his three brothers-in-law, and merchants Nathan Appleton and Israel Thorndike pooled their resources and founded the Boston Manufacturing Company at Waltham, Massachusetts. Using the power of the Charles River, they opened the first textile mill in the United States that spun and wove cotton fabric in the same facility. Lowell and a machinist named Paul Moody patented a power loom in 1815.

To meet the demand for labor in his mill, Lowell created what became known as the Waltham-Lowell System. He and his associates hired young women, aged between fifteen and thirty-five, from the surrounding farms to work in the mills. The women lived in company boarding houses, where as many as six of them shared a single room. They worked twelve to fourteen hours a day, six days a week, with a short break for lunch. The factories were loud and hot, and bits of thread and cotton filled the air. New workers were partnered with more experienced women, who taught them the skills they needed for the job. Most signed on for a one-year contract and worked an average of four years for the company.

The boarding houses were managed by chaperones who made sure the workers watched their manners and went to church regularly. The women ate together, and curfew was usually 10 p.m. The women were offered educational opportunities after work, but considering their long work days, taking advantage of those offerings was difficult. These conditions seem extreme now, but at the time, they were considered quite enlightened.

Read more about the Lowell Mills in the National Register

National Archives Identifier: 530414

Lowell died in 1817 of pneumonia, and in 1821, his partners moved the operation north to the Merrimack River because the Charles River couldn’t generate enough power to keep the mill functioning. The partners renamed the town “Lowell” in honor of the founder and set out to revolutionize the textile manufacturing system. Lowell soon became the center of the Industrial Revolution in the United States. By 1840, the mills employed about 8,000 workers, most of them women.

Although wages had started out around $3 to $5 a week (about $90 to $149 in 2022 dollars), a depression spurred the company’s board to cut wages in February 1834 by fifteen percent. In response, the workers staged a strike and withdrew their earnings from two local banks, which caused a run on them.

1860 Census showing “Mill Hands” living in the Lowell Mill Dorms

Source: NARA’s Records of Rights Exhibit

The strike failed, but the board was startled and chagrined by the workers’ actions. In October 1836, the board tried to raise the rent of the boarding houses. In response, some 1,500 workers walked off their jobs and stayed off until the board rescinded the rent increase.

The strength of the collective will of the Lowell mill girls, as they came to be called, contributed directly to their ability to control their own destinies. In 1845, a group of female workers created the first women’s union, the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association. The association lobbied the Massachusetts legislature for shorter work days and better working conditions. Progress was slow, but by 1853, they had succeeded in getting the workday shortened from twelve hours to eleven.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above