Smoke and Mirrors

“Smoking or nonsmoking?” It’s probably been awhile since you’ve heard that question, but it used to apply almost everywhere: restaurants, hotel rooms, public buildings and even airplanes.

Throughout history, cigarettes were a staple of American culture. While searching the Archives catalog, it was common to find photographs of notable historical figures with a cigarette in their hand, and even physicians touted the benefits of a mild, relaxing cigarette.

So what changed, and how? Let’s dive into the Archives (no smoking, please!) and find out.

In this issue

Cigarette smoking among Americans got a tremendous boost during World War I…

…there’s fire

In January 1964, a committee of 10 experts presented a report to Surgeon General Luther L. Terry, M.D. …

Clearing the air

The representatives of the tobacco industry were naturally petrified by the prospect of the release of the Surgeon General’s report…

History Snack

Where there’s smoke…

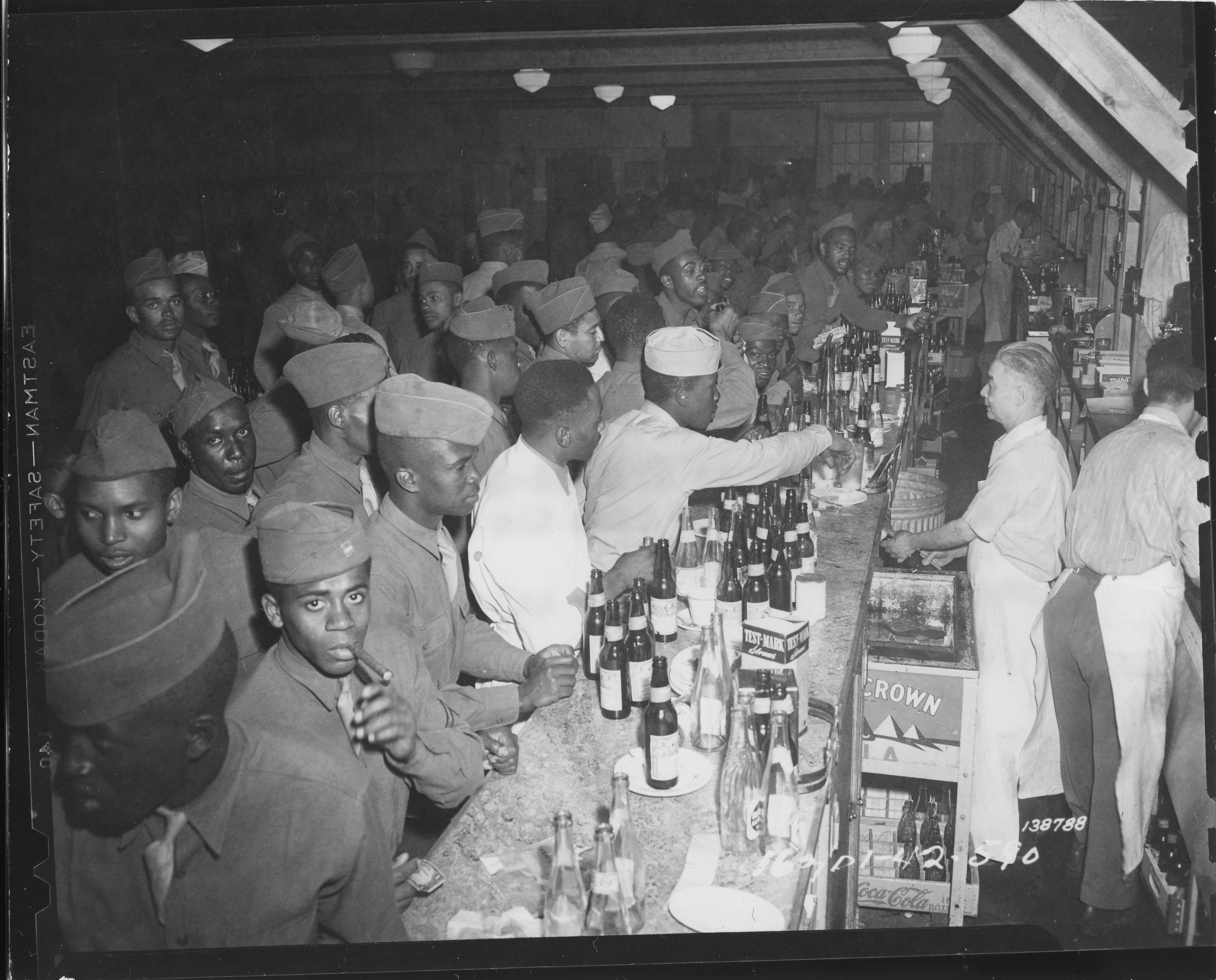

Cigarette smoking among Americans got a tremendous boost during World War I, when the Army started distributing cigarettes in field rations to GIs to help them calm their nerves on the battlefield. These were “manufactured,” or machine-rolled, cigarettes, as opposed to hand-rolled cigarettes, and before the United States entered the war to end all wars, Americans smoked only about 18 million “tailor-made” cigarettes a year. By the time the war was over, that number had skyrocketed to 45 million. In addition to smoking themselves, U.S. servicepersons used cigarettes as currency and as good-will gifts to the residents of the countries they were liberating, handing them out along with chocolate and chewing gum as they moved on to the next battlefields.

Red Cross distributes cigarettes at Verdun

(7 minutes 41 seconds, NO SOUND)

Source: National Archives Identifier: 24971, page 9

Letter to Herbert Hoover — Crime is Due to the Use of Cigarettes

National Archives Identifier: 6854435

Then the war ended, and all those smokers came home, and the Roaring Twenties were on with a vengeance. Smoking and drinking bootleg liquor were national pastimes, along with dancing the Charleston, driving fast cars and listening to jazz. Lots of younger women took up smoking too, an act of rebellion that shocked many of the older generations. Religious people and social reformers were horrified, mostly because they saw smoking as a gateway to much worse habits like drug and alcohol use, but opposition to smoking didn’t gather much steam, despite the fact that doctors were reporting increasing incidences of lung diseases like asthma, emphysema and cancer.

By the middle of the century, nearly half of the U.S. population smoked, and most of the other half accepted the practice as socially acceptable. It seemed like everybody smoked everywhere and all the time—at home, in restaurants, in bars, on trains and airplanes, in automobiles, in hospitals, in public buildings. Movie stars smoked, both on screen and off, and many of them, including John Wayne and Ronald Reagan, had endorsement deals with tobacco companies. Cartoon characters smoked on their shows and in cigarette commercials, most notably Fred and Wilma Flintstone. Characters in novels, male and female, smoked like chimneys. If a smoker ran out of cigarettes, a vending machine stocked with their favorite brand was doubtless close at hand.

Tobacco companies did everything in their power to protect the market they had and expand on it. They advertised in newspapers and magazines, on billboards and on the radio and television. They distributed baseball cards in cigarette packs. They sponsored sporting events. Their mission was to convince Americans that smoking made smokers look sexy and cool. They conveniently ignored that it was also addictive and deadly.

…there’s fire

In January 1964, a committee of 10 experts presented a report to Surgeon General Luther L. Terry, M.D., titled Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General. The committee had spent just over a year, from November 1962 through January, reviewing more than 7,000 scientific papers with the aid of 150 consultants at the National Library of Medicine at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. On January 11, 1964, Dr. Terry released the report to the public. He had deliberately chosen that day because it was a Saturday, which would give newspaper reporters time to review the report for the Sunday editions, but their stories would not immediately roil the stock market. The report announced for the first time that the U.S. government recognized that cigarette smoking had bad effects on smokers’ health.

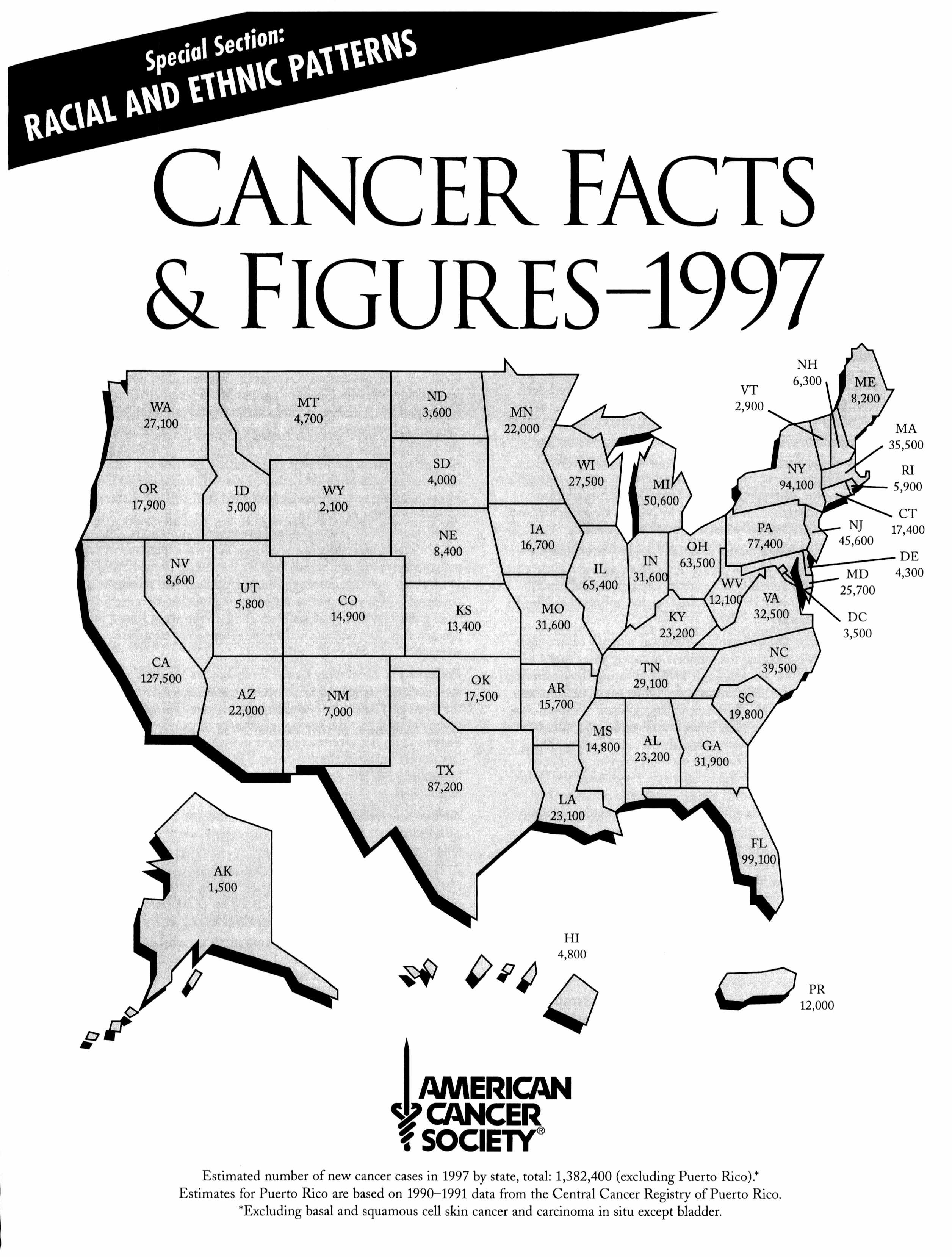

Dr. Terry later said that Smoking and Health “hit the country like a bombshell. It was front page news and a lead story on every radio and television station in the United States and many abroad.” The committee had found that the evidence against smoking was damning: the report stated that smokers experienced a 70% increase in mortality and a nine- to 10-fold greater risk of developing lung cancer compared to nonsmokers, and the odds were much worse for heavy smokers. Furthermore, smoking contributed to smokers developing chronic bronchitis, emphysema and coronary heart disease, and smoking during pregnancy reduced the birth weight of newborn babies.

American Cancer Society Report, page 5

National Archives Identifier: 26413455, page 5

Despite all that bad news, the federal government was slow to take action, but in 1966, Congress passed legislation that required cigarette packages to carry a label indicating that smoking was bad for one’s health. That initial warning was pretty weak, but over time, it has been increased to many different statements supported by graphic illustrations, such as, “WARNING: Smoking reduces blood flow to the limbs, which can require amputation.”

Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act of 1966

Source: Federal Trade Commission

The Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act, signed into law by President Richard M. Nixon in April 1970, outlawed advertising cigarettes on radio and television as of January 2, 1971. In 1997, the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement banned advertising of cigarettes in 46 states on billboard, outdoor and public transportation advertising. In 2010, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act forbade tobacco companies from sponsoring music, sporting and cultural events and from putting their logos on apparel, hats or other products.

The report did result in a decrease in smoking. When it was released, more than 50% of the U.S. population smoked. Dr. Terry himself had smoked two packs a day until just prior to the release of the report, at which point he quit cold turkey. The first group that started to quit en masse were doctors, who, incidentally, had also been among the heaviest smokers.

The bad news about smoking just kept on coming. New studies found that smoking contributed not only to the development of lung cancer, but also to esophageal, bladder, pancreatic and stomach cancer. In 1972, the Surgeon General reported that secondhand smoke was dangerous to nonsmokers’ health. In 1980, the first Surgeon General’s report investigating the effects of cigarette smoking on women’s health was issued, and again, the news was not good.

Clearing the air

Phillip Morris document telling Congress they will self regulate

National Archives Identifier: 26416520, page 2

The representatives of the tobacco industry were naturally petrified by the prospect of the release of the Surgeon General’s report, which they correctly surmised would have a devastating effect on their livelihoods. They countered by disputing its scientific contentions in writing and in public forums and by fighting tooth and nail to continue to advertise their product in every avenue available to them. But their most successful method of attacking the report was funneling massive amounts of cash into the campaigns of politicians who were sympathetic to their cause.

“Tobacco companies poured $4.5 million in 1997—the most ever for a year without a presidential election—into congressional campaign chests and national political party coffers, an analysis of public interest-group databases, Federal Election Commission data and other sources reveal,” wrote David Phinney in his article “Congress Awash in Big Tobacco Money” for ABC News on May 6, 1998. “And members of Congress who got direct donations voted with Big Tobacco nine to 15 times more often than those who didn’t accept campaign cash from makers of cigarettes, cigars, chewing tobacco and other products, according to ABCNEWS.com’s analysis.”

Tobacco Campaign Contributions

National Archives Identifier: 26413495, page 2

Meanwhile, nongovernment groups started taking action to stop smoking in their communities. In the 1970s, the American Medical Association divided its meetings into “Smoking” and “Non-Smoking” sections. During the same period, airplanes were similarly segregated. In 1977, the American Cancer Society took its fight against cigarette smoking to the public when it sponsored the “Great American Smokeout,” issuing a challenge to smokers to stop smoking for a day. Supporters of the society hoped that participants would go on to kick the habit entirely. The Smokeout has since evolved into an annual event held on the third Thursday of November each year that encourages people to quit smoking or to make a plan to quit.

In 1981, Surgeon General C. Everett Koop declared that the United States should become a smoke-free country. Koop, who served from 1981 through 1989, issued eight reports during his tenure on the health hazards of smoking, including one on the addictive qualities of nicotine.

Elena Kagan Q & A on youth smoking (1998)

National Archives Identifier: 55034106, page 1

In 1988, the state of California banned smoking on all short airplane flights, and in 1990, smoking was banned on all domestic flights in the United States. Delta Airlines became the first U.S. airline to ban smoking on international flights in 1995. That same year, California banned smoking in restaurants that did not have bars and in offices, manufacturing plants and enclosed work spaces. Twenty-nine states, including California, have now enacted bans on smoking in enclosed workplaces, including restaurants and bars.

Despite the steady and constant opposition of the tobacco industry, the number of smokers in the United States has dropped precipitously, from about 50% of the population in 1964 to about 12.5% in 2020. Since about 1990, a renewed focus on battling teen smoking, new warnings about the dangers of smoking and higher taxes on cigarettes have all contributed to lower smoking rates.

View this profile on InstagramNational Archives Foundation (@archivesfdn) • Instagram photos and videos