7 Minutes to Midnight

The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists maintains a metaphorical clock, called The Doomsday Clock, but it doesn’t tell time. The placement of the minute hand on the clock instead represents how close humanity is to self-inflicted destruction from unchecked advances in science and technology. Every second the minute hand creeps closer to midnight, the threat to humanity grows.

From its inception in 1947, the Doomsday Clock has served as a bellwether of U.S./Russian relations. The clock was created in the aftermath of hydrogen bomb testing: 7 minutes to midnight. As Nixon began his policy of detente: 12 minutes to midnight. It was 17 minutes to midnight when the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991. For the last three years, the clock has remained at 100 seconds.

Sixty years ago at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis, the clock stood at its original time – 7 minutes until midnight. With the world on the brink of nuclear disaster, President Kennedy and a close group of advisors met to avoid the worst outcome. While now we look back at that time as an epic game of diplomatic chess, the Archives holds the documents and notes written in the moment that detail their thoughts, decisions and actions. This week, we explore the records that chronicle one of the most intense 13 days of American history.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

The Voices of ExComm

In the fall of 2012, in observation of the 50th anniversary of the Cuban missile crisis, Martin Sherwin, an American historian who had spent his entire career studying the history of nuclear proliferation, published an article in Prologue Magazine, the National Archives’ publication. Titled “One Step from Nuclear War. The Cuban Missile Crisis at 50: In Search of Historical Perspective,” the article is a painstaking and incisive analysis of the events in October 1962 that brought the United States and the Soviet Union perilously close to thermonuclear war. The source of their dispute was the Soviet Union’s deployment of nuclear missiles on the island of Cuba, a mere 90 miles from Florida.

Sherwin’s article is particularly interesting because it draws upon transcripts and tape recordings of the meetings that took place in the Oval Office and the Cabinet Room, where most of the discussions about the crisis took place. The Executive Committee (ExComm) that convened to discuss the situation initially included 16 members. Sherwin writes that the record of the meetings “lay bare the dynamics between senior advisers and contradicted many of their recollections. It exposed their confused views of Soviet objectives, revealed their analytical instincts (and lack thereof), and exposed whether they had what can only be referred to as good sense. And it raised deeply troubling questions about the judgment of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.”

Read more here

One Step from

Nuclear War

The Cuban Missile Crisis at 50: In Search of Historical Perspective

Source: NARA’s Prologue magazine

We invite you to read Martin Sherwin’s article, which will be time well spent. Martin Sherwin graduated from Dartmouth College in 1959. In 1971, he received his Ph.D. in history from the University of California, Berkeley. He founded the Nuclear Age History and Humanities Center at Tufts University, from which he retired in 2007. He also taught at George Mason University and Princeton. In 1975, he published “A World Destroyed: The Atomic Bomb and the Grand Alliance,” which was a finalist for the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize. “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” co-written with Kai Bird, won the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for biography or autobiography, the National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography, and the English-Speaking Union Book Award. In 2020, Sherwin published “Gambling with Armageddon: Nuclear Roulette from Hiroshima to the Cuban Missile Crisis,” which specifically addresses the Cuban missile crisis. Martin Sherwin died on October 6, 2021, at his home in Washington, D.C.

Phone call between JFK and Adlai Stevenson

regarding Soviet Missile Buildup in Cuba

(14 minutes 28 seconds)

Source: JFK Library

Recording of JFK’s radio address

regarding Soviet presence in Cuba

(17 minutes 46 seconds)

Source: JFK Library

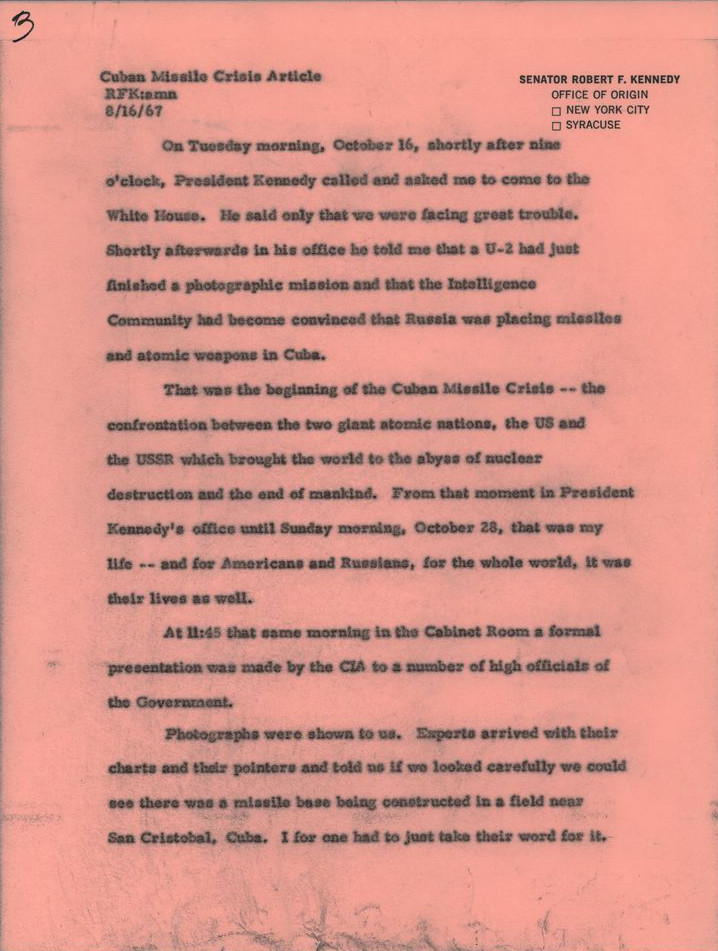

As Told by Bobby

Full Draft of an article by Robert F. Kennedy on the Cuban Missile Crisis, later published as the book, “Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis.”

Source: JFK Library – Digital Identifier: JBKOPP-SF079-001-p0001

In 1967, Robert F. Kennedy, who was his brother’s attorney general at the time of the crisis, recorded his recollections of the events of the Cuban missile crisis in a very detailed article, now in the holdings of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, an affiliate of the National Archives. Despite RFK’s dispassionate, almost deadpan style, the harrowing possibilities of how the situation could have played out are always close to the surface in his report.

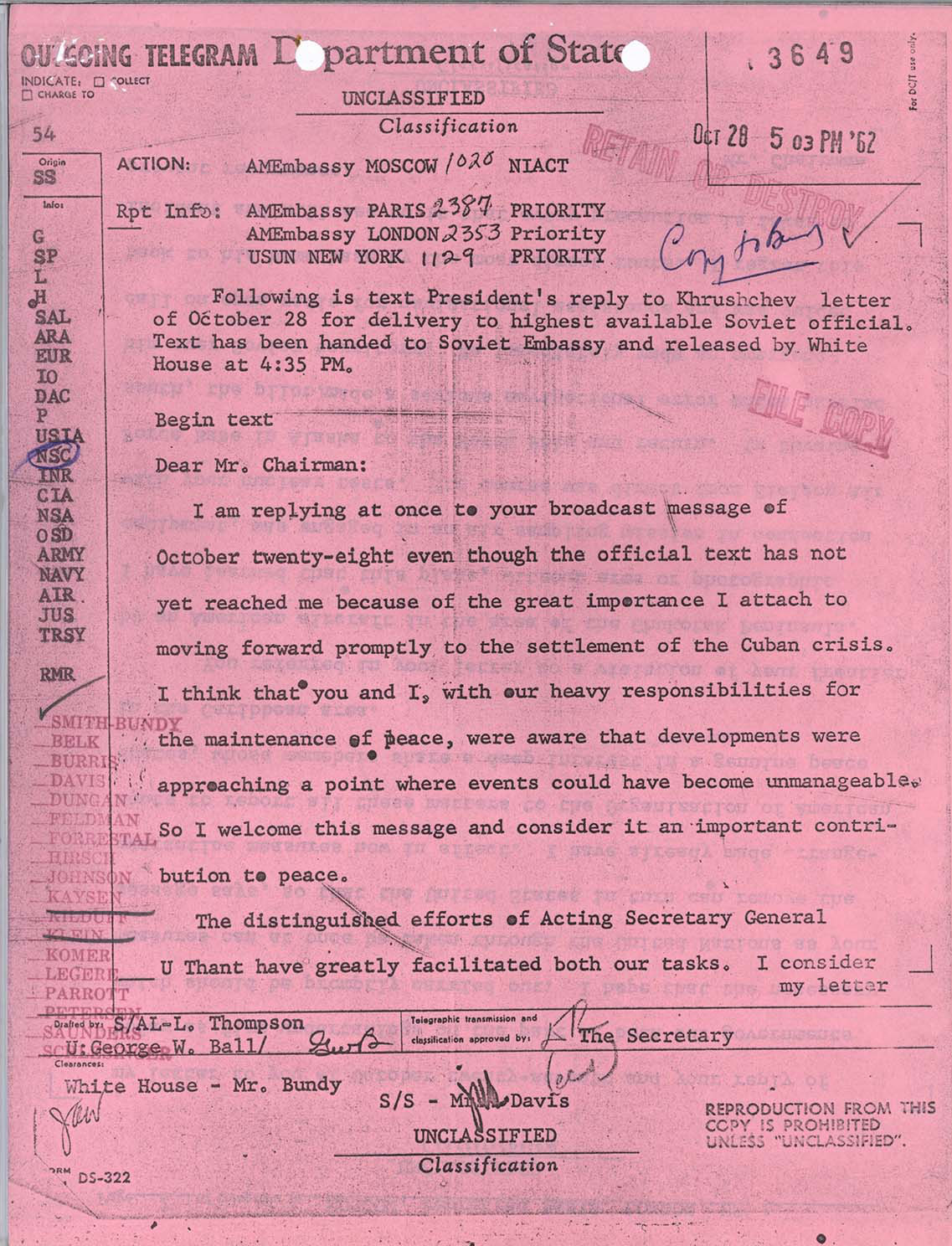

JFK’s response to Khrushchev’s radio address

Source: NARA’s Prologue Magazine

In the end, John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev managed to negotiate an arrangement that both nations could agree to, and a nuclear war that would have ended life on planet Earth was avoided. Robert Kennedy’s article became the basis of his book “Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis,” posthumously published in 2011 with a foreword by the eminent historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, who had served as a special assistant to John F. Kennedy.

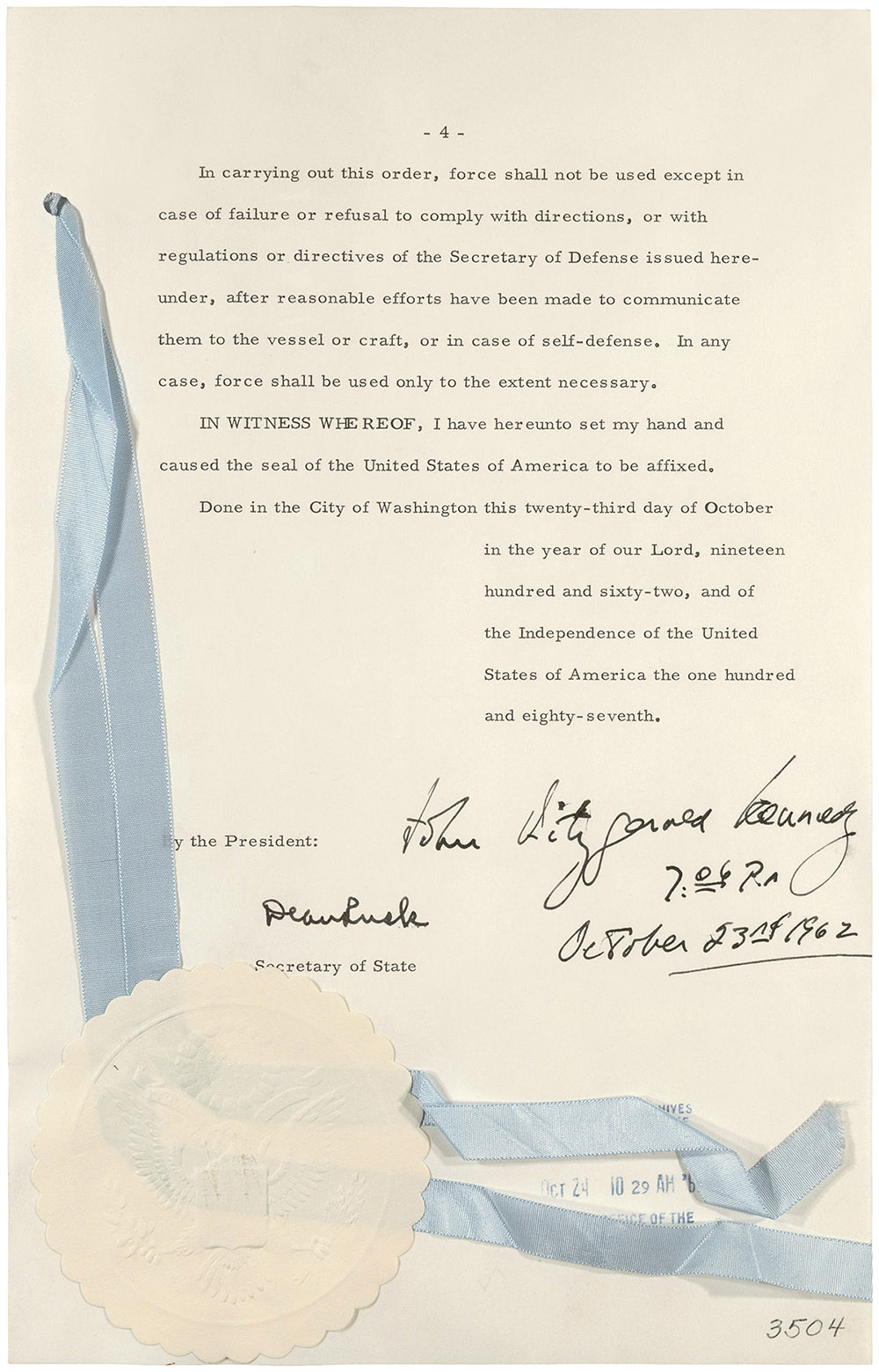

War of the Words

JFK’s order to quarantine weapons of mass destruction to Cuba

Source: NARA’s Prologue Magazine

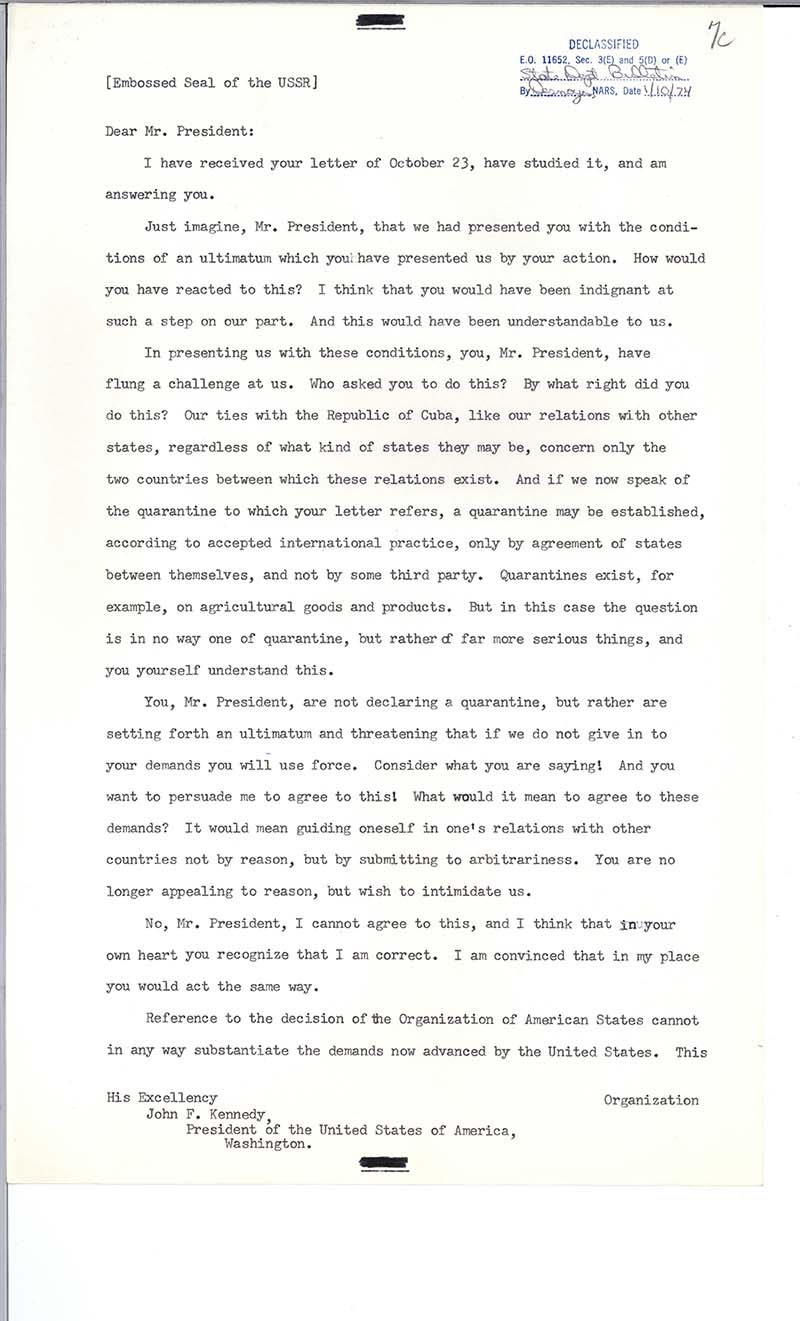

On October 23, in response to Nikita Khrushchev’s continued refusal to halt the deployment of nuclear weapons in Cuba, President John F. Kennedy ordered a naval “quarantine” of Cuba to keep any additional nuclear missiles from reaching the island. He avoided calling the action a “blockade,” which would have been a clear violation of international law. A “quarantine” was designed to only prevent offensive military equipment from being shipped to Cuba, not civilian materials.

Premiere Khrushchev’s response to JFK’s quarantine of Cuba

Source: NARA’s Prologue Magazine

The quarantine line consisted of nearly 200 ships strung out along an arc about 500 miles from northeast to southeast of Havana. Kennedy also included the Organization of American States in the order, and several member nations agreed to send naval vessels to participate in the action. The order that Kennedy signed authorizing the quarantine is in the holdings of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, an affiliate of the National Archives.

Bird’s-Eye View

Aerial Photo – 23 October 1962, MRBM Launch Site 2, Sagua La Grande, Cuba

NARA’s The NDC blog

By mid-September 1962, U.S. government officials had begun to suspect that the Soviet Union was constructing military bases and moving personnel into Cuba. The USSR ignored President Kennedy’s warnings to Premier Nikita Khrushchev that the U.S. would not tolerate such actions, so the U.S. started sending reconnaissance aircraft to take photographs of the suspicious maneuvers.

MRBM Field Launch Site No. 1 in San Cristobal, Cuba, 14 October 1962

National Archives Milestone Documents – National Archives Identifier: 193926

On October 16, 1962, President Kennedy called his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, to the White House for a briefing about the situation. “Photographs were shown to us,” the younger Kennedy recalled in his article on the subject, now in the holdings of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. “Experts arrived with their charts and their pointers and told us if we looked carefully we could see there was a missile base being constructed in a field near San Cristobal, Cuba. I for one had to just take their word for it.”

Take Note

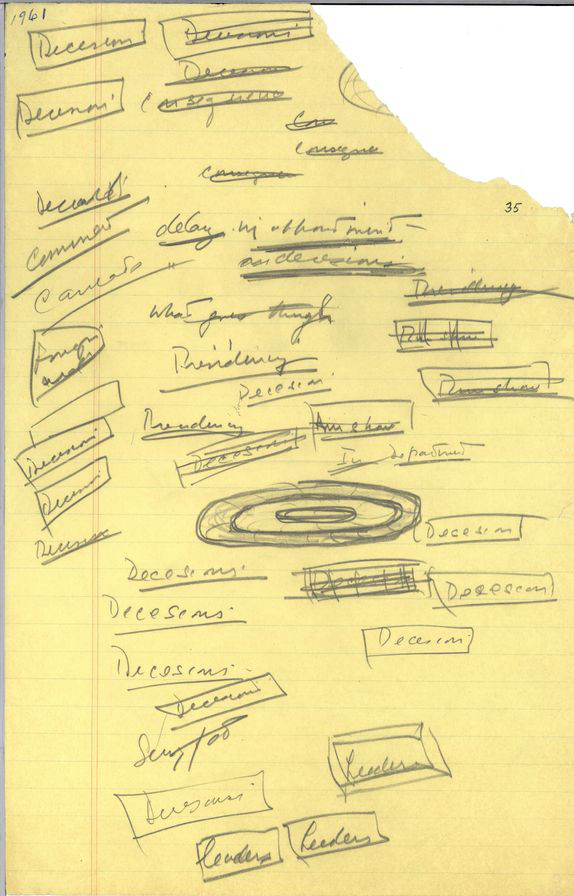

JFK’s notes

Source: JFK Library – Digital Identifier: JFKPOF-115-009-p0030, page 30

When your teacher is talking a mile a minute, it’s hard to take notes that will make sense to you later—but just imagine that you’re trying to take notes about a situation that might end in a thermonuclear war! It’s no wonder John F. Kennedy’s notes from his meeting about the Cuban missile crisis are a little hard to decipher.