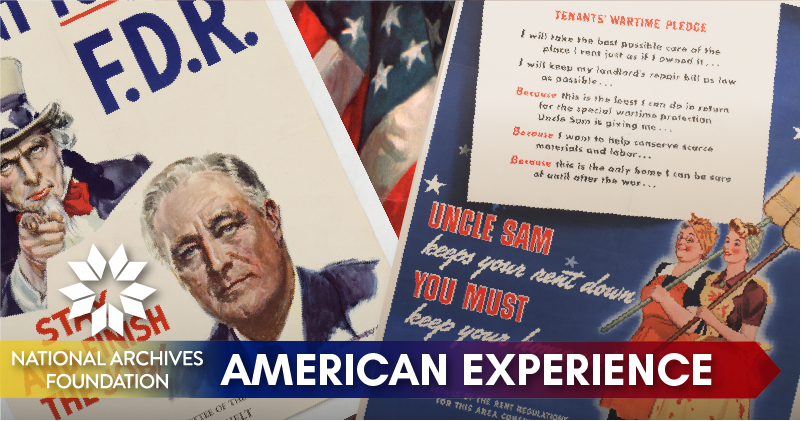

Power of Persuasion

The public has heard a lot about President Biden’s plans for the first 100 days of his Administration. The President who came up with the concept of the first 100 days was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, when the nation was mired in the Great Depression. As soon as he’d taken the oath of office, Roosevelt immediately introduced a flurry of legislation aimed at achieving his “New Deal”: providing relief for the needy, economic recovery, and financial reform.

Source: NARA’s Educator Resources

FDRs Fireside Chats were radio broadcasts addressed directly to the American people as a means to sway public (and Congressional) opinion. He explained the aims of his new policies, discussed current events, and reassured listeners. He spoke to his audience as his equals, his tone warm, encouraging and never condescending. People across the nation gathered around their radios to hear what the President had to say.

All governments use their megaphones to persuade audiences at home and abroad. The U.S. is no different. In fact, as the Founders were finalizing the Declaration of Independence, they gave the text to a local Philadelphia printer to print copies and get the word out. Nowadays public service campaigns, press conferences, social media, diplomats, posters, late night shows, and even leaflets dropped from planes all carry a message the government wants to be heard.

So this week, join us as we look back at how the government and our leaders framed tragedies and triumphs, world wars and milestone moments of the past.

Cocktail Conversations with Derek Brown

Freedom Summer Inspiring Young Voters Today

🌪️

OR OR OR OR

The Spin Doctor

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

P.S. There’s still time to register for our two upcoming programs this month. First, a spirited conversation with cocktail expert Derek Brown on temperance, prohibition, and the alcohol free cocktail movement” this Friday, February 19. On February 24, we’ll explore “Freedom Summer Inspiring Young Voters Today,” a program about how a civil rights murder in 1964 has inspired a national movement of young people to vote and engage in civic life today. Register here!

We Can Do It!

National Archives Identifier: 44266042

You’ve probably seen the famous World War II posters of Uncle Sam and Rosie the Riveter, but many other countries, including China, Russia, Italy and France, also issued posters that urged their citizens to do their part to support the war effort. The Royal Indian Navy distributed this poster describing opportunities “for Educated Boys between the ages of 15-17 and for Youths of 17-1/2 to 26.” The poster also lists other positions such as writers, sick berth attendants, stewards, cooks, signal and wireless operators, and seamen and stokers. The poster was designed by artist Frank Norton and printed by the Times of India Press. At that time, India was still part of the British Empire.

Poster art from WWII

Source: NARA’s The Unwritten Record blog

The National Archives holds a vast and varied collection of World War II propaganda posters. A digital version of the exhibition”Powers of Persuasion: Poster Art from World War II,” which was on view at the National Archives Museum in Washington, D.C. from May 1994 to February 1995, features eleven of the posters and one sound file that were included in the original exhibition. If you are interested in more, check out the well known

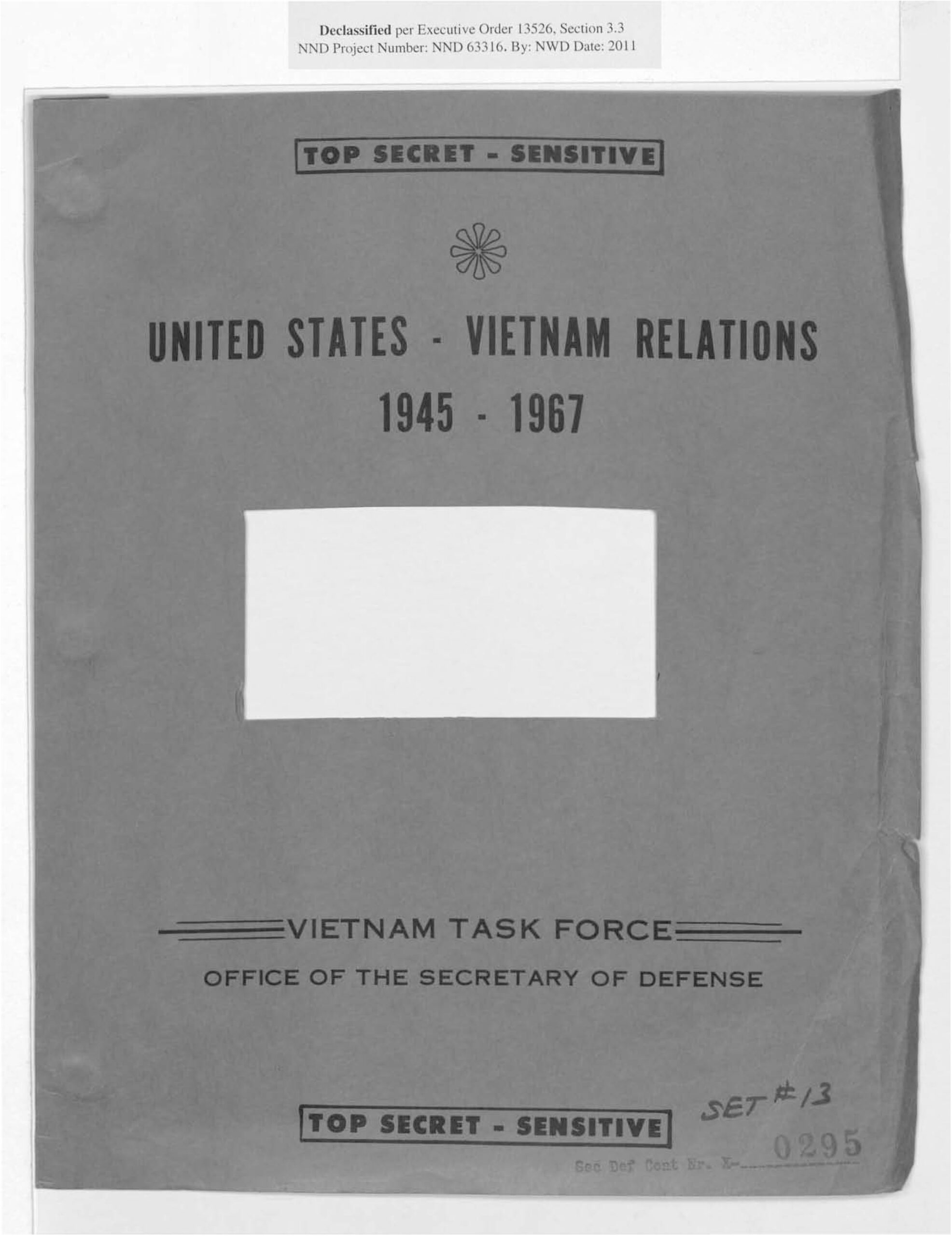

Why Viet-Nam?

On July 26, 1965, President Lyndon Baines Johnson held a press conference to address the question of why the United States was committed to fighting a war in Southeast Asia.

A partial transcript of his speech is located in the holdings of the Archives.

National Archives Identifier: 5890517

The U.S. Army later produced a 31-minute film titled Why Viet-Nam? It begins with footage of Johnson asking that question at the press conference. It then echoes Johnson’s question three more times, backed by dramatic music and featuring images of the fighting in Vietnam.

Then the film compares the situation in Vietnam to the events of September 30, 1938, when British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain signed the Munich Agreement with Adolf Hitler in an attempt to avoid having to go to war with Germany. The film characterizes the agreement as a failure of concession. The implication is that the United States, having long been committed to protecting the democratic ambitions of South Vietnam, would not make the same mistake that Britain had and thus would prevent communism from spreading throughout all of Southeast Asia.

The Archives holdings include a copy of the film, the first two minutes of which have been digitized. [NB – at the time of reposting this newsletter to the Archives Experience in July 2022, all three reels are now available online and have been added below]

Reel 1

(8 minutes 28 seconds)

National Archives Identifier: 2569861

Reel 2

(9 minutes 58 seconds)

National Archives Identifier: 2569861

Reel 3

(10 minutes 42 seconds)

National Archives Identifier: 2569861

A National Loss

Source: Reagan Library

It happened 35 years ago last month. Tuesday, January 28, 1986 began as any ordinary day for most Americans. President Ronald Reagan was working his way through a series of meetings when Vice President George H. W. Bush and National Security Advisor John Poindexter came in and told him that the Space Shuttle Challenger had exploded shortly after take-off. It was,the President noted in his diary, “A day we’ll remember for the rest of our lives.”

Challenger

Many of those who recall the disaster also remember the speech that President Reagan delivered that evening. He spoke of the seven members of the Challenger’s crew – Michael Smith, Dick Scobee, Judith Resnik, Ronald McNair, Ellison Onizuka, Gregory Jarvis, and Christa McAuliffe. He spoke directly to their families, expressing his and First Lady Nancy Reagan’s condolences. He spoke to the nation’s children, for many of whom the event was probably their first experience of a national loss. And he spoke to the nation as a whole. “The future doesn’t belong to the faint-hearted,” he said. “The future belongs to the brave.”

President Reagan’s speech has long been considered a masterwork of public rhetoric. With its plain language and quiet tone, it describes both the courage of the crew and the excruciating pain of losing them. It expresses Reagan’s genuine empathy and affirmed, yet again, his status as “the Great Communicator.” Certainly, with the calm sincerity of his words, Reagan paid tribute to the crew and evoked a national period of mourning. He also most likely forestalled, at least for a little while, the onslaught of questions, investigations, and inquiry that followed the tragedy.

“I Want You” to Create a Propaganda Poster

Create a Propaganda Poster

Source: FDR Library

During World War II, the U.S. Office of War Information (OWI) Bureau of Graphics distributed millions of posters that conveyed encouraging, inspirational, and warning messages to the public. The posters urged men to join the military, women to join the workforce, and the general public to watch their words, lest foreign spies learn secrets that could injure the war effort.

Visit the website of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, located in Hyde Park, New York to learn how to make your very own propaganda poster.

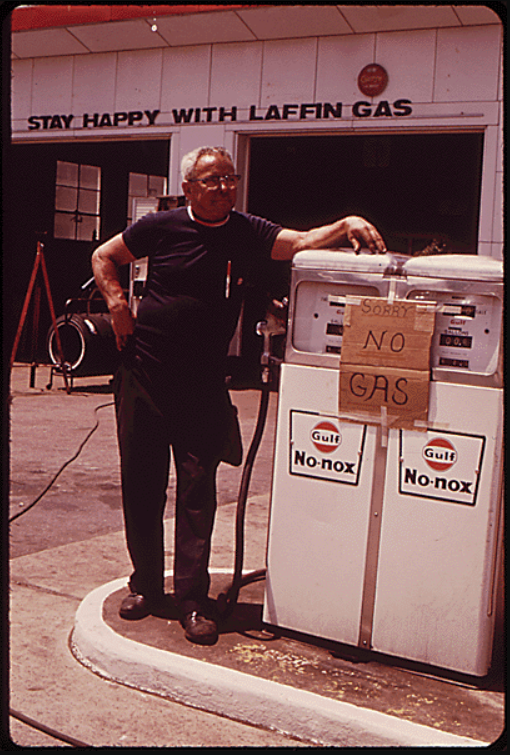

It Is a Crisis of Confidence

In the summer of 1979, the United States was beset by an energy shortage, rising unemployment and double-digit inflation. President Jimmy Carter was doing his best to deal with these problems, but the results of his efforts were decidedly mixed.

On July 15, 1979, exactly three years to the day after he had accepted the Democratic Party’s nomination for President of the United States, Carter addressed the nation, describing a “crisis of confidence” he felt Americans were experiencing. The principal subject of the speech was the energy crisis, and Carter outlined ways in which the public could conserve energy and thus put the United States on a more independent and certain footing.

July 14, 1979

Source: Carter Library

A common thread that runs through all presidential administrations is the idea of speaking directly to the people to break up logjams in Congress. Carter directly follows this line of reasoning in his “Crisis of Confidence” speech.

What subject would you tackle in a speech? What kind of language would you use to persuade your listeners to agree with you? Write a short speech you’d give to express your opinions and win your audience’s support.