Pass the potatoes, hold the politics

Thanksgiving. A time to gather around the table with your loved ones, enjoy a meal and watch some football. But wait–did someone just bring up the midterms? Or say, “I read a tweet that said…”? Good thing we are serving up a mashed refresher on civic engagement, U.S. government and how our government was built with how to handle differences in mind.

Just like a family around a dinner table, the founding fathers bickered about policy and knew conflict within our government was inevitable.

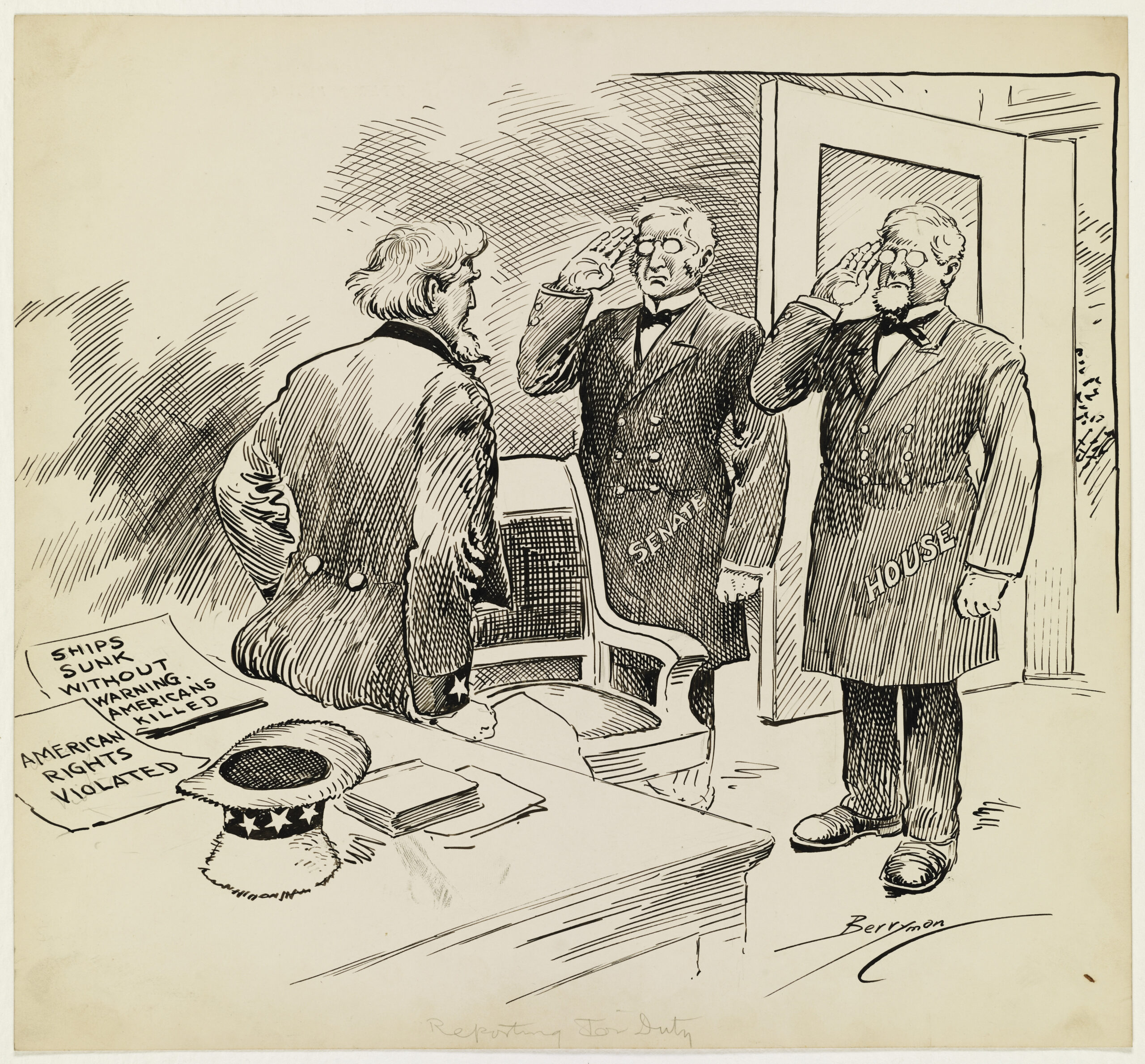

This week, we go beyond “checks and balances” and bring you the observations of Clifford Berryman. His familiar political cartoons will hand you a few good conflict resolution skills to have in your back pocket this Thanksgiving. Just in case.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

P.S. Love these cartoons? Check out the full

ebook “Representing Congress.”

Different Branches, Same Tree

In the U.S. Constitution, the founding fathers created three branches of government—the executive, legislative and judicial branches. Congress, the legislative branch, enacts laws, the president as the executive branch enforces them and the judicial branch, the courts, interprets them. Ideally, as this cartoon depicts, the branches work well together, and the nation runs smoothly. In reality, the course of true government rarely runs smooth.

The members of the House of Representatives serve two-year terms, while the members of the Senate serve six-year terms. Members of either house can introduce bills that can become laws, and support or opposition in either chamber can result in a bill being enacted or derailed. For a bill to become a law, it has to be passed in the same, identical form by both houses of Congress. Naturally, this requirement sets the scene for potential wrangling, high-hatting, deal-making, speechifying, grandstanding and compromise.

The House and Senate have been at odds since their creation; one represents people by population, the other makes all the states equal. As you can see in Berryman’s cartoons, the slow pace of the Senate has long been irksome for both the president and the House. A combination of long terms, low turnover and complicated rules make the Senate a place where you won’t find “fast-paced” in the job description. Luckily for the House, they have a counter-balance. Their close proximity to their districts and people make it easy to sneak “niche” needs into longer, more complicated bills. Who doesn’t want a side of local infrastructure with their defense spending bill?

Party’s Over

Beginning with the establishment of the United States, different political parties have held sway, but since the American Civil War, the Republican and Democratic Parties have been the two main ones in power, although their positions at that point in time would hardly be recognizable right now. (No, we did not heed George Washington’s warnings about political parties. Or foreign wars. Or…)

Still, for more than 150 years, the donkey and the elephant have lined up at the starting line for each election, sometimes along with the odd third- or fourth-party candidate, to run the race. A common situation with Congress, too, is that members of the different parties almost never agree on what they’ve achieved, come the end of the legislative session. Sometimes their interpretations are so different that it can be hard to believe they’re talking about the same event.

Especially in the Senate, rules protect the political minority, whereas in the House, power rests with the dominant party and the Speaker of the House. Our government has never been without political divides. Before it was the Democrats versus Republicans, it was the progressives versus the political machines; the anti-slavery Republicans versus the dying Whig party; the federalists versus the anti-federalists. There was even a time when we had two bitterly divided factions called the mugwumps and the stalwarts.

Stamp of Disapproval

Once the two houses of Congress have hammered out their differences and passed an identical bill, they must send it on to the president, who then can either sign it into law or veto it. If they veto it, the bill goes back to Congress, which has the option of letting it die or of trying to override the veto. Doing so requires a vote of two-thirds majority of both houses. If Congress achieves this, the bill becomes law without further presidential action.

Here’s where our friend “partisan conflict” reappears—there’s much less likelihood of a conflict between the executive and legislative if they’re controlled by the same party. But if not? We’re in for some fun, and that’s veto-proof! Some famous vetoes include Calvin Coolidge kills farm subsidies, Ulysses S. Grant strikes down inflating the money supply and Ronald Reagan vetoes sanctions against South Africa. The president who used the most vetoes? FDR with 635, although it helps that he was in office the longest. Conversely, both Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama used the veto rarely, just 12 times each over the course of their respective eight-year presidencies.

Passing Judgment

Untitled

National Archives Identifier: 6012025

How could we forget the third branch of government: the judiciary? The Senate also has the power to confirm or deny the appointment of high officials, including members of the Supreme Court of the United States. Even though judges are supposed to be nonpartisan, they still have the power to uphold or strike down laws enacted by a Democratic or Republican Congress.

The nomination hearings for such officials can sometimes be loud and drawn-out, especially if political differences come into play. As Berryman shows, Supreme Court nominees better have thick skins before they appear before the U.S. Senate!

Who’s the boss?

Reorganization of Congress

National Archives Identifier: 306100

From time to time, we hear a lot of talk about the need for term limits, so people can’t be elected to political office more than a specified number of times. But as this cartoon aptly points out, we already have term limits—they’re called elections! If the people don’t like the way a particular politician is representing them, they are empowered to vote them out and send them packing!