Ours to Define

Welcome to the Archives Experience debut series: A Republic, If You Can Keep It. In celebration of Constitution Day, we’re chronicling the creation of this document—but these aren’t the stories we’ve all heard before. Instead, we’ll look at how the National Archives holdings show just how close we came to an entirely different form of government and how “We the People” triumphed in the end.

If there’s one thing we expect from the Supreme Court, it’s answers to our most fundamental questions. From the scope of its early powers to the role of government in modern day, the court has always been a place the American people and other branches of government look to for guidance.

But the court leaves more questions unanswered than not. And in the course of shaping our nation, there’s one big question they’ve left to us and us alone to answer……

Unanswered Questions

Some constitutional scholars have argued that Founding Fathers added the judicial branch of American government to the Constitution as an afterthought, but there is ample evidence that the court system was on their minds throughout the process of writing the document that governs our republic. On May 28, 1788, Alexander Hamilton wrote in The Federalist No. 78,

It is more rational to suppose that the courts were designed to be an intermediate body between the people and the legislature, in order to keep the latter within the limits assigned to their authority. The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts.

Thus, Congress is charged with making the laws, and the executive branch with sometimes proposing them and always with signing them into law, but the courts are responsible for interpreting them. But the Constitution is rather vague about the specifics of the country’s court system, so it fell to Congress to more clearly define the Supreme Court. On September 24, 1789, President George Washington signed into law the Judiciary Act of 1789, which stipulates in Section 1,

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the supreme court of the United States shall consist of a chief justice and five associate justices, any four of whom shall be a quorum, and shall hold annually at the seat of government two sessions, the one commencing the first Monday of February, and the other the first Monday of August.

(An aside: Modern day readers of this law may be surprised to learn that the court did not always have nine justices.)

Hamilton-Federalist #78

NARA’s Founders Online/figcaption>

Federal Judiciary Act of 1789

NARA’s Milestone Documents

The Jay Court

That same day the Judiciary Act became law, Washington nominated John Jay for chief justice of the United States and John Rutledge, William Cushing, Robert H. Harrison, James Wilson, and John Blair, Jr., as associate justices. Congress confirmed all six nominees, but Harrison declined his nomination, so Washington then nominated James Iredell in his stead.

John Jay served as chief justice of the Supreme Court for just a little less than six years, but in that time, he firmly established the course on which it continues to this day. He and his associates spent much of the first three years of his tenure establishing rules and procedures and presiding over cases at the circuit court level. However, in 1790, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton wrote Jay asking the court to endorse legislation that would assume the states’ debts. Jay answered that the court was only obliged to rule on the constitutionality of cases that were being tried before it. He also declined to advise George Washington about whether a particular foreign policy was or was not constitutional.

In Hayburn’s Case, (1792), the Supreme Court was asked to rule on whether certain nonjudicial duties could be assigned by Congress to the federal circuit courts in their official capacity. This was the first time that the Supreme Court addressed this issue. Congress eventually reassigned the duties in question, and the Supreme Court never issued a judgment. This case is important because the court found that it could not impose certain duties on Congress because they are separate branches of government.

Madison letter on Hayburn’s Case (1792)

NARA’s Founders Online/figcaption>

Perhaps Jay’s greatest contribution, however, is that he set the precedent that the court would only make its determinations based on existing case law, not as an advisory role. This is the founding principle of the Supreme Court’s actions.

The Marshall Court

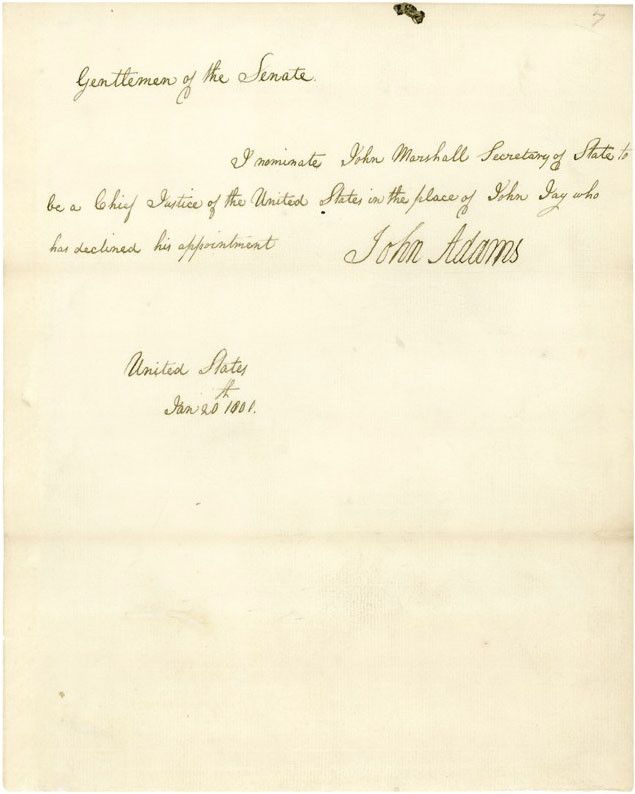

Chief Justice John Marshall was the fourth to serve in the office and still holds the distinction of having served the longest, with a tenure of 34 years from February 4, 1801, until July 6, 1835. He instituted several innovations, including that the court issues a single majority opinion and accompanying minority opinions, if necessary. Prior to his tenure, each judge had written his own opinion for each case.

Nomination of John Marshall to the Supreme Court

NARA’s DocsTeach

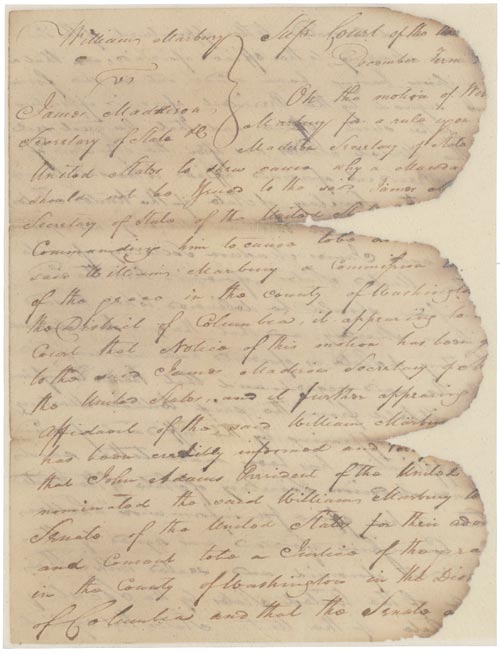

But Marshall made several sweeping edits that profoundly directed the way the court operates. In the 1803 decision in Marbury v. Madison, Marshall stated, “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases, must of necessity expound and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the courts must decide on the operation of each.” In this decision, he specifically gave the Supreme Court the power to determine the constitutionality of laws.

The Marshall court also instituted the process of judicial review, by which the judiciary can review executive, administrative, and legislative actions and can invalidate such actions if it finds they are unlawful or unconstitutional. Judicial review is one of the checks and balances given to the judiciary in the separation of powers.

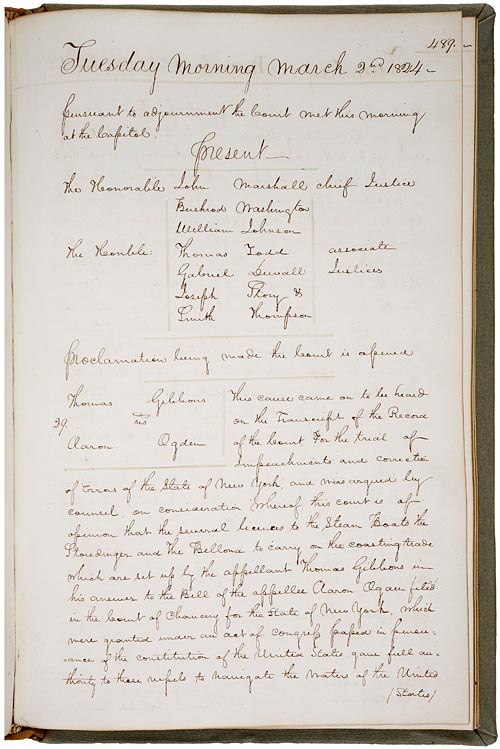

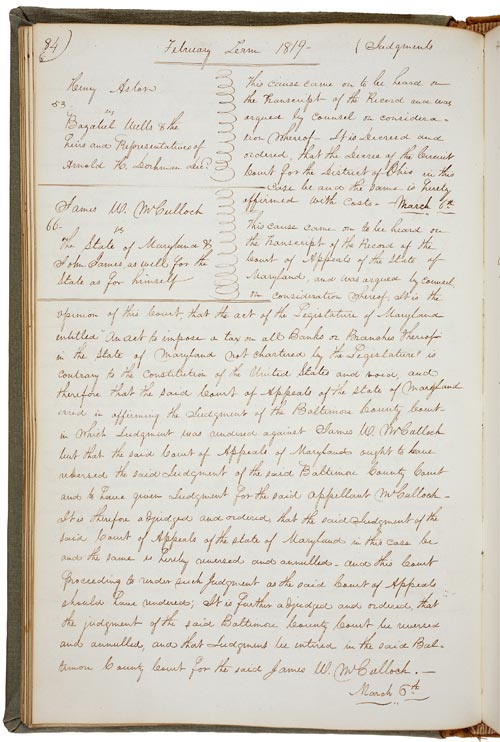

Other powers that Marshall gave to the Supreme Court were the ability to regulate interstate commerce (Gibbons v. Ogden, 1824) and that the federal government had sovereignty over the states (McCulloch v. Maryland, 1819).

Decision in Marbury v. Madison

NARA’s Milestone Documents

Decision in Gibbons v. Ogden

NARA’s Milestone Documents

Decision in McCulloch v. Maryland

NARA’s Milestone Documents

What’s a Republic?

There’s one area that the Supreme Court has declined to rule on, however, and that’s the definition of a republic. We talked a few weeks ago about the Guarantee Clause, which states that people in every state had the right to a republican form of government. But what is a republic? The Supreme Court won’t say. In the 1840s, the state of Rhode Island had an internal rebellion over the charter of its state government. Each side hoping to prove its validity through the Guarantee Clause, they took their cases to the Supreme Court. But in the 1849 decision in Luther v. Borden, the court declined to pick a side, saying that the definition of republican was a political question the court had no right to answer.

In the years since Luther, the court has upheld this precedent time and again.

So what IS a republic? That’s up to us. Our series has been based on Ben Franklin’s iconic quote, “A Republic, if you can keep it.” This challenge, for the people to participate in and define our own republic, is as salient today as when Ben Franklin first said it at the dawn of our new government. Republics require the education of and involvement from all citizens, and the Foundation and our partners at the National Archives are well positioned to be leaders in this space. But we need your help.

We are just days away from the end of our Civics Education Fund appeal. If you love stories like these and want to help make them accessible to students, educators, and all American citizens, you can double your impact by making a gift before September 30.

We hope you’ve enjoyed celebrating Constitution Month with us. Next week, the Archives Experience will be back to our regularly-scheduled programming.

View this profile on InstagramNational Archives Foundation (@archivesfdn) • Instagram photos and videos