One if by Land, Two if by Sea

Since our nation’s beginning, communication has played an essential role in how history unfolded. On the night of July 4, 1776, colonists learned of America’s Independence through the Dunlap Broadsides – large copies of the Declaration of Independence to be posted in public spaces. With the radio, telephone, TV, Twitter and TikTok still more than a century or two away, broadsides were the common way of spreading the most important news.

Over the years communication has trotted, sparked, broadcast and clicked across the country.

- American mail rode in on the Pony Express, tying the East to the Wild West.

- In January 1838, Samuel Morse demonstrated his telegraph for the first time. The invention – his single-wire telegraph – revolutionized communication worldwide, making it possible to send messages over great distances in just a few hours.

- President Franklin Roosevelt’s fireside chats became an iconic means to connect with the country during his administration.

- Even though Jimmy Carter’s campaign was the first to use email, it wasn’t until 1993 that President Bill Clinton became the first President in history to have a public email address. That same year, the White House launched its first website.

From there…well, I’m confident you can fill in the rest of the 140 characters. From lanterns to lunar phone calls, how Americans “heard the news” of triumph, hardship and everything in between shaped public opinion.

As technology and innovation propel us forward, this week we take a look back at where we’ve been – you’ve got mail!

📬

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

P.S. – Join me and FDR Presidential Library Director Paul Sparrow on January 28 for a discussion of the 20th century’s most influential power couple. We will explore the impact of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt together and apart. Register here.

History-making Memos STOP

Morse’s telegraph was used to send any number of important messages, both personal and official. Morse sent the first official one in the United States from just outside the Supreme Court Chamber in the Capitol building on May 24, 1844: “What hath God wrought?”

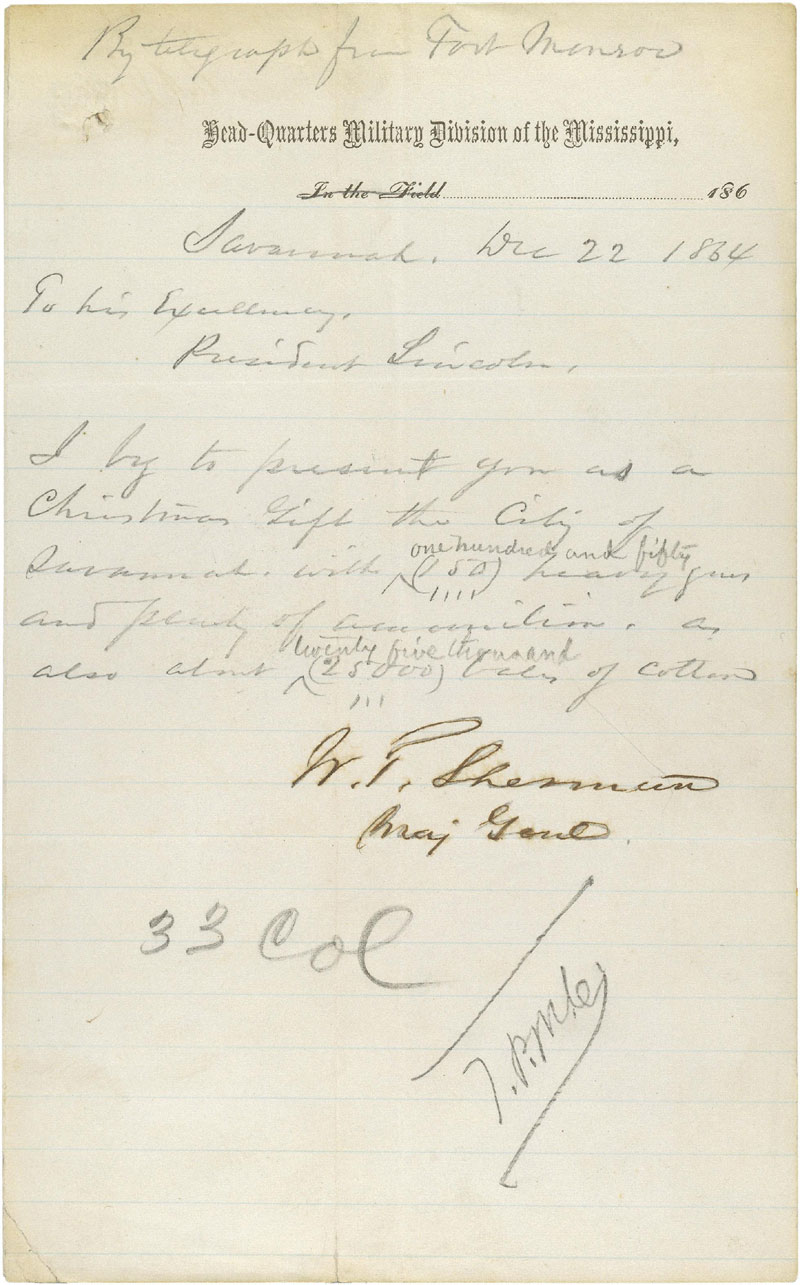

During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln used the telegraph to communicate with his generals. When the city of Savannah, Georgia, surrendered to General William Tecumseh Sherman, he sent the commander-in-chief a telegraph stating: “I beg to present you, as a Christmas gift, the city of Savannah, with 150 heavy guns and plenty of ammunition, and also about 25,000 bales of cotton.”

And the completion of the Transcontinental Railway on May 10, 1869, was announced by telegraph in a single word: “Done.”

Wings for War

If you are at war and can’t be sure a message would get to headquarters by land, how about sending it by air? During World War I, the humble carrier pigeon was often the hero, transporting messages to military headquarters and other units on and behind the front lines. One of them, Cher Ami, flew through withering friendly fire to deliver a message to military headquarters that the shells were falling on their own men. He was wounded, but he recovered. For his bravery, Cher Ami was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palm by the French government.

Transatlantic TV

On July 10,1962, NASA launched Telstar I – the first active communications satellite in space. Thirteen days later, it relayed the first-ever transatlantic TV signal, showing Europe pictures of the Statue of Liberty, the Eiffel Tower, part of a baseball game and remarks by President Kennedy on the value of the American dollar.

CBS news anchor Walter Conkite, also on the broadcast, later said, “We all glimpsed something of the true power of the instrument we had wrought.”

Undercover Ink

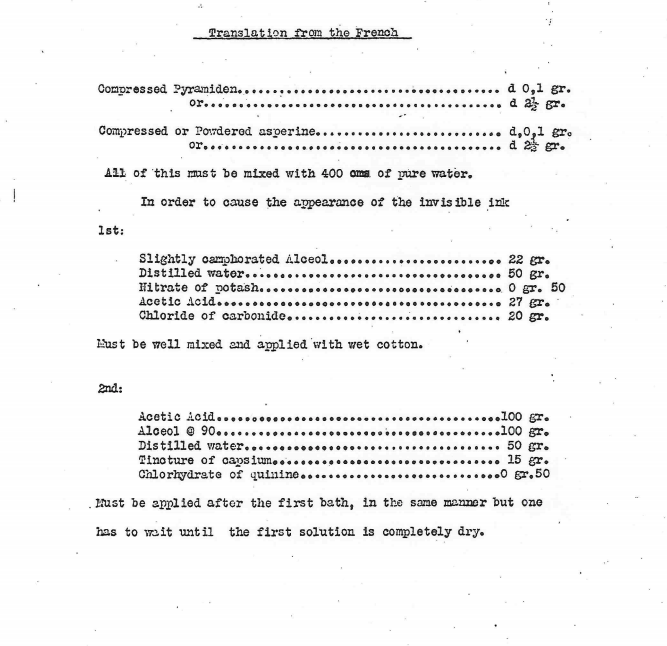

Do you ever wish you could send a message that only the recipient could read? During World War I, the Germans created invisible inks so they could safely communicate their battle plans. In collaboration with the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, documents in the National Archives about the formulas for the ink were declassified in 2011. One formula (written in French with translation) is described in this June 14, 1918 Office of Naval Intelligence document. The invisible ink’s ingredients – compressed or powdered aspirin mixed with “pure water” – and the method of causing it to appear are provided.

Unbreakable Code

During both World War I and II, the U.S. military needed a fool-proof way to communicate with their troops—one that the enemy could not decipher. The solution was the Code Talkers, Native Americans who were trained to encrypt the messages they sent over the radio in their native tongues. The Code Talkers were members of the Choctaw, Cheyenne, Comanche, Cherokee, Osage, Yankton Sioux, Navajo, Kiowa, Hopi, Creek, Seminole, and other tribes. Their “code” was never broken, and the Code Talkers are credited with helping win both wars.

During World War II, Philip Johnston was the initiator of the Marine Corps’ program to enlist and train the Navajos as messengers. Although Johnston was not a Navajo, he grew up on a Navajo reservation as the son of a missionary and became familiar with the people and their language. Johnston was also a World War I veteran and knew about the military’s desire to send and receive messages in an unbreakable code. He hit upon the idea of enlisting Navajos as signalmen early in 1942 when he read a newspaper story about the Army’s use of several Native Americans during training maneuvers with an armored division in Louisiana.