The New Face of Justice

Every Supreme Court nomination is historic – the lifetime tenure of a seat ensures that vacancies are rare and highly coveted. In 233 years, no Black woman has served on the court. When President Joe Biden nominated Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson to sit on the highest court in the land, he set the stage for this to end. If confirmed, Judge Jackson will join the ranks of Thurgood Marshall and Clarence Thomas, both trailblazers in the legal profession and on the court.

This powerful judicial body has long determined the legal status of the Black community with notable cases – Dred Scott v. Sandford, Plessy v. Ferguson, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Loving v. Virginia, and Shelby County v. Holder, just to name a few.

As Women’s History Month continues, we honor this moment by looking at Archives documents that highlight the role of Black women in the legal system, the transformation of the court, and the ever-evolving face of justice.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Suing for Seating

Montgomery bus

When you think of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Rosa Parks is probably the first, if not only, name that comes to mind. Parks’ refusal to give up her seat to a white passenger was the catalyst for a thirteen-month–-long boycott that ultimately led to the U. S. Supreme Court’s ruling on the desegregation of public transportation. But there’s a crucial part of this story that’s often left out: Rosa Parks’, the NAACP’s, and the Montgomery Improvement Association’s bus boycott put public pressure on the city, but a group of four other Black women were the ones who brought the boycott to the courthouse steps.

The Montgomery Improvement Association Booklet

National Archives Identifier: 2641476

On March 2, 1955, fifteen-year–old Claudette Colvin boarded a Montgomery bus. When she was told to get up for a white passenger, Colvin replied that she had paid her fare and sitting in her seat was her Constitutional right. Minutes later, police boarded the bus to arrest her. One month later, on April 19, Aurelia Browder, thirty seven, was arrested, charged, and fined for the same act. That October saw two more arrests of Black women: Susie McDonald, who was seventy and walked with a cane, and eighteen-year–old Marie Louise Smith.

Judgment from Aurelia Browder et al. v. W. A. Gayle et al.

National Archives Identifier: 279206

All four of these women joined a lawsuit with the aim of ending bus segregation both in Montgomery and the state of Alabama. Because Browder was in the middle of the age range of the plaintiffs, she was chosen as the lead for the case. Among the defendants listed were Montgomery Mayor W. A. Gayle, Montgomery’s chief of police, and the bus company and two of its drivers. A fifth woman was originally included in the suite, Jeanetta Reese, but she pulled out at the last minute when she faced extreme duress by her white employer. By the time the case was filed on February 1, 1956, the boycott had been in full swing for two months.

On June 5, the U.S. District Court ruled that segregation on municipal buses violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Both the city and state appealed, but the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the decision in an opinion issued on December 7, 1956.

Signed with an X

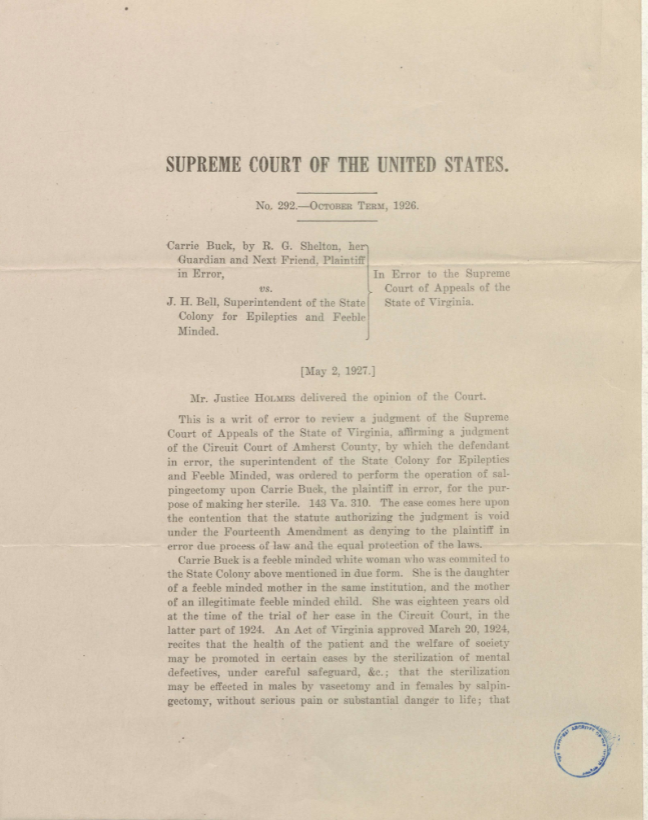

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes is one of the most famous writers in the history of the Supreme Court, but in 1927, one of his opinions left a black mark on the court that almost matched the malevolence of Roger Taney’s opinion in Dred Scott v. Sandford. His exact words were “three generations of imbeciles is enough,” and he was referring to the Buck family, specifically Emma Buck and her daughter Carrie.

Supreme Court Opinion

in Buck v. Bell

Source: DocsTeach – NARA’s Education Division

At the age of seventeen, Carrie Buck became pregnant with a daughter. Her inability to care for the baby led to her admittance to the Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded. This was at the height of the eugenics movement in the United States, and in 1925, Virginia passed a law allowing for sterilization due to mental “defectiveness.” To test its constitutionality, the institution’s superintendent, Dr. Albert S. Priddy chose Carrie Buck as a test case, citing her as “unfit to exercise the proper duties of motherhood” because of her “anti-social conduct and mental defectiveness.”

Virginia Sterilization Act

In a series of hearings, testimonies, and court decisions that upheld Virginia’s sterilization law, the U. S. Supreme Court handed down its decision in Buck v. Bell (Dr. Bell was the superintendent who succeeded Dr. Priddy). This was the case that ultimately allowed Carrie Bell’s sterilization on October 19, 1927. She was the first to be involuntarily sterilized, but not the last: over 8,300 people in Virginia alone were subjected to this cruel law.

Shart [sic] Analysis of the Hereditary Nature of Carrie Buck

Source: NARA’s Education Updates blog

Buck v. Bell

(Case File #31681)

National Archives Identifier: 45637229

The overturning of Buck v. Bell was not straightforward, but two sisters from Montgomery, Alabama were major players in repealing eugenics laws throughout the U.S. Mary Alice (aged fourteen) and Minnie (aged twelve) Relf were two Black teenagers who lived in public housing and were receiving medical care and birth control from a federally funded family planning facility. This made them vulnerable to social workers, who sought them out and brought them to the hospital. Their mother, unable to read or write, was under the impression that the girls were to receive contraception shots and signed a consent form with an “X.” Mary Alice and Minnie were given tubal ligations.

Read about how Relf v. Weinberger was presented in a memo to President Ford

Source: Box 22, folder “Justice – Court Cases (3)” of the Philip Buchen Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library

When Mr. and Mrs. Relf realized their daughters had been sterilized without their consent, they filed a lawsuit with the help of the Southern Poverty Law Center. Although Carrie Buck, the woman who set the precedent for these eugenics laws, was white, over 65% of all involuntary sterilizations were conducted on Black women.

materials for

Buck v. Bell

from Docsteach

The Supreme Court ruled on Relf v. Weinberger on March 14, 1974, stating that federal dollars could not be used for forced sterilizations and established standards for informed consent. Simultaneously, the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (now called Health and Human Services) withdrew the regulations that enabled forced sterilizations, causing many parts of the case to be moot.

The Commonwealth of Virginia issued an official apology to its victims in 2002.

“Three Generations of Imbeciles are Enough” — The Case of Buck v. Bell

The Eighty-third

Vice President Joe Biden and Attorney General Loretta Lynch

National Archives Identifier: 219775281

The Eighty-third Attorney General of the United States was unlike any other. On April 27, 2015, Loretta Lynch became the first Black woman attorney general in United States history. After an impressive legal career, she was nominated by President Barack Obama to lead a department that she’d been in service to, on and off, since 1990.

ICTR (International Criminal Tribunal Rwanda)

National Archives Identifier: 52873447

The daughter of a librarian and a preacher, Loretta Lynch was born in Greensboro, North Carolina, and received both her undergraduate degree and law degree from Harvard University. Her passion for the law and civil rights was inspired by stories about her grandfather, who helped people move north to escape Jim Crow laws. She spent her early years in the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Brooklyn prosecuting violent crimes, narcotics busts, and civil rights violations. Even when she was in private practice, her focus remained on human rights. In 2005, Lynch was appointed by the UN’s International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda to investigate allegations of witness tampering and false testimony related to the country’s 1994 genocide of the Tutsi tribe.

President Barack Obama with Loretta Lynch

National Archives Identifier: 219774997

Lynch’s tenure was historic, and it is not surprising that the Attorney General’s Office focused on civil and human rights cases throughout her time there. Notable cases under her leadership included charging the Ebenezer A.M.E. church shooter, Dylann Roof, with a hate crime, investigating the death of Chicago resident LaQuan McDonald, and charging a militia group occupying the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge.

Read President Obama’s statement on the confirmation of Lynch

as Attorney General

National Archives Identifier: 231363372

![]()

Civics Corner: The Road to SCOTUS

The Investiture Ceremony for Justice Sonia Sotomayor

National Archives Identifier: 176551376

Remarks Announcing the Intention To Nominate Sandra Day O’Connor To Be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

Source: Reagan Presidential Library

It’s a long road to becoming a Supreme Court Justice, involving two out of three of the branches of government. Once the President announces their nominee, here’s what happens.

- The nomination is sent to the Senate Judiciary Committee, a smaller group of Senators that holds a hearing with the nominee present. At the hearing, they ask questions of the nominee, and Senators who are both in favor of and opposed to the nominee state their cases. What kinds of questions are asked at these hearings?

Listen to Senators Ted Kennedy and Bob Dole talk about the Senate Judiciary Hearings for Judge Robert Bork, who was nominated by President Ronald Reagan. Source: JFK Presidential Library

- The Senate Judiciary Committee issues a recommendation to the rest of the Senate by voting.

- The Senate debates the merits of the nominee. Because the rules don’t limit debate, this can go on for a while.

- The Senate votes on whether to confirm the President’s choice. Before 2017, 60 votes were needed to confirm a nominee, but now, only 51 are needed

The nominee is sworn in, but because there’s no standard for the ceremony, two different ceremonies have evolved over the years. One typically is a public ceremony at the White House. The other, called the Investiture Ceremony, is typically private and administered by the Chief Justice. It is also the occasion at which the new Justice receives their robes.

Now Hiring!

Collection of letters between Washington and Johnson

Source: NARA’s Founders Online

Unlike many federal jobs, the qualifications for a Supreme Court Justice aren’t outlined in the Constitution. Although the great majority of Supreme Court Justices after the year 1900 have held law degrees, many in our nation’s early history did not.

Collection of letters between Washington and Chase

Source: NARA’s Founders Online

Twenty-eight SCOTUS Justices have the equivalent of an undergraduate degree. Of those, five did not have any formal college or university education at all, and instead learned the law through apprenticeships (the historical version of an internship). Three of those five were nominated by our first president, George Washington. The letters between them all are extensive and are preserved in the Archives’ Founders Online database.

Collection of letters between Washington and Iredell

Source: NARA’s Founders Online

Judge Jackson, the current nominee, attended Harvard Law school, like many of her predecessors. She shares her alma mater with current Justices Gorsuch, Kagan, Breyer (whom she is nominated to replace), and Chief Justice Roberts.