Monumental Moments

Originally built to memorialize the Great Emancipator and one of the most consequential presidents in history, the Lincoln Memorial has played a role in many important events in its one-hundred year history. I actually have one such story that lives large as part of our family lore.

One of dad’s favorite things to do when family came to visit in the summer was to give them a driving tour of downtown Washington, D.C., at night. Part of that tradition included driving up to the monuments and parking (yes, it was allowed then – and yes, the station wagon had one row of seats that faced backwards) and making our way up the stairs. I loved to see the monuments and memorials glow under the lights at night. To a kid, everything was larger than life.

On one particular visit when I was seven, the family arrived at the Lincoln Memorial. We reached the top step, and most of my family were drawn straight toward the towering figure of Lincoln presiding over the memorial. I drifted off to one of the side chambers and found myself mesmerized by the wall memorializing the words of the Gettysburg Address. Little did I know, it had been ten minutes and everyone was piling back into the car when one of my cousins asked, “Where’s Patrick?” A wave of panic ensued. The entire family raced back up to the memorial and fanned out across the site to find me. They found me soaking it all in, standing next to Lincoln. As my dad – out of breath – arrived on the scene with a swarm of cousins, I asked, “Do you think I’m taller than his leg?” which elicited a roar of laughter (and helped me avoid the lecture about wandering off). Needless to say, at our next stop, I was under my dad’s close observation.

The nation’s capital has an extraordinary skyline that is anchored by the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials, the Capitol building and Washington Monument. Lincoln’s memorial has a legacy of its own. Over the last century, it has become synonymous with civic engagement. This week, we draw on records from the Archives to celebrate the Lincoln Memorial’s centennial with stories from concept design to historic events to tourist attraction.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

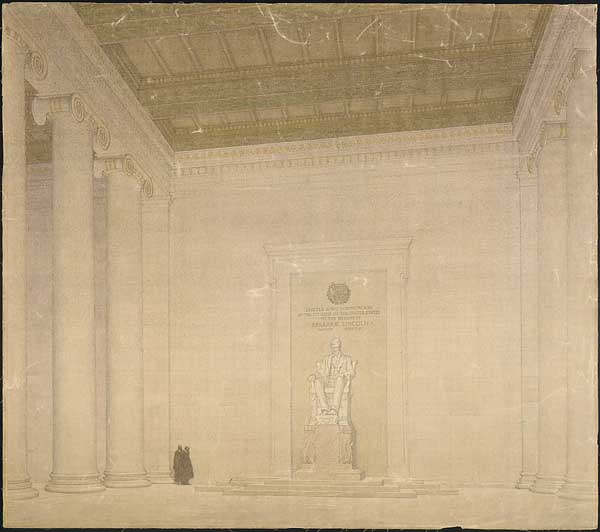

What Could Have Been

East Elevation of Lincoln Memorial

National Archives Identifier: 12059542

The Lincoln Memorial, that iconic temple built to honor the man who saved the United States from dissolution, was dedicated on May 30, 1922. The Lincoln Memorial Commission selected architect Henry Bacon’s design from among several contenders, including a ziggurat-style monument and Mayan-temple style building, both proposed by John Russell Pope, who designed the National Archives building. Besides the one that was finally settled on at the end of the National Mall, several other locations were considered, including the Soldier’s Hospital and Meridian Hill.

Henry Bacon’s Competition Proposal for a Monument to Abraham Lincoln

National Archives Identifier: 2581318

Bacon designed the memorial in the style of a Greek Doric temple because he wanted to link the sixteenth President to the birthplace of democracy. The exterior is made of Yule marble from Colorado. With one for each state at the time of Lincoln’s death, the thirty-six fluted columns are each 44 feet high and 7 ½ feet in diameter at the base.

But as it stands, with its commanding view down the National Mall to the Washington Monument and then to the U.S. Capitol nearly two miles distant, the Lincoln Monument seems to invite people to gather there. The eighty-seven steps, which symbolize the four-score and seven years that Lincoln immortalized in the Gettysburg Address, begin at the Reflecting Pool and rise to the main portal of the memorial. The steps are interspersed with a series of wide platforms where people seem naturally to come together.

Architect John Russell Pope (who designed the Archives!) proposed various designs and sites for the memorial

Bending toward Justice

If you stand inside the Lincoln Memorial in front of the statue of Abraham Lincoln, facing the U.S. Capitol building, on the wall to your right you can see inscribed Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, and on your left, you will see his Second Inaugural Address. Given that Lincoln presided over the Civil War, which was fought to end slavery on American soil and to preserve the Union, it is telling that the word “slavery” only appears once in the memorial, in the latter address:

“If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which in the providence of God must needs come but which having continued through His appointed time He now wills to remove and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him.”

Nevertheless, from the very beginnings of the memorial, the issue of race was always present. At the dedication on May 30, 1922, the attending crowd was segregated. Only in the group of surviving Union soldiers did Blacks and whites sit next to one another.

In 1939, the celebrated American contralto Marian Anderson tried to rent Constitution Hall in Washington to hold a concert, but the Daughters of the American Revolution, who owned it, refused her because she was Black. Many prominent people, including First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, worked on Anderson’s behalf, and instead, she gave a concert on Easter Sunday in front of 75,000 people at the Lincoln Memorial. Some historians consider that event the first salvo of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.

On June 29, 1947, President Harry S. Truman became the first American President to address the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Speaking from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, Truman promised to protect the civil rights of all Americans – “And when I say all Americans – I mean all Americans,” he insisted.

Quite possibly the most famous words spoken at Lincoln Memorial are those of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, which he delivered on August 28, 1963, to an audience of 200,000 who were participating in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The spot where King stood, eighteen steps from the top landing of the memorial, is now inscribed in recognition of the event.

When King was killed, he had been planning the Poor People’s Campaign, which was a protest that aimed to bring people who represented all those living in poverty in the United States to Washington to advocate on their behalf. After King’s assassination, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference went ahead with the campaign. The protesters arrived in the nation’s capital and built an encampment, called “Resurrection City,” on the south side of the Reflecting Pool and adjacent to the Lincoln Memorial. The activists met with legislators and called for new laws aimed at easing poverty.

In the end, the police cleared out the encampment when the group’s permit to camp on federal land expired. Although the Poor People’s Campaign did not achieve any of its immediate goals, it is credited with having influenced the later passage of important legislation that has helped ease the burdens of poverty.

And finally, in January 2009, when Barack Obama was sworn in as President of the United States, several celebratory events for his inauguration took place at the memorial. This building, which many consider a sacred space, has truly become a gathering place for all of us.

![Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. [Leaders of the march] Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. [Leaders of the march]](http://archivesfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/ae-2022-05-31-a2-nai-542056.gif)

![Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. [Leaders of the march]](http://archivesfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/ae-2022-05-31-a2-nai-542056.gif)

Lincoln Memorial Dedication, 1922 (7 min 2 sec – no sound)

Record Group 111: Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, 1860 – 1985

Historical Film, No. 1169A

Harry Truman speaks to the NAACP (1 min 27 sec)

Universal News Volume 20, Release 52, June 30, 1947

Obama celebrates his inauguration at the Lincoln Memorial (3 min 32 sec)

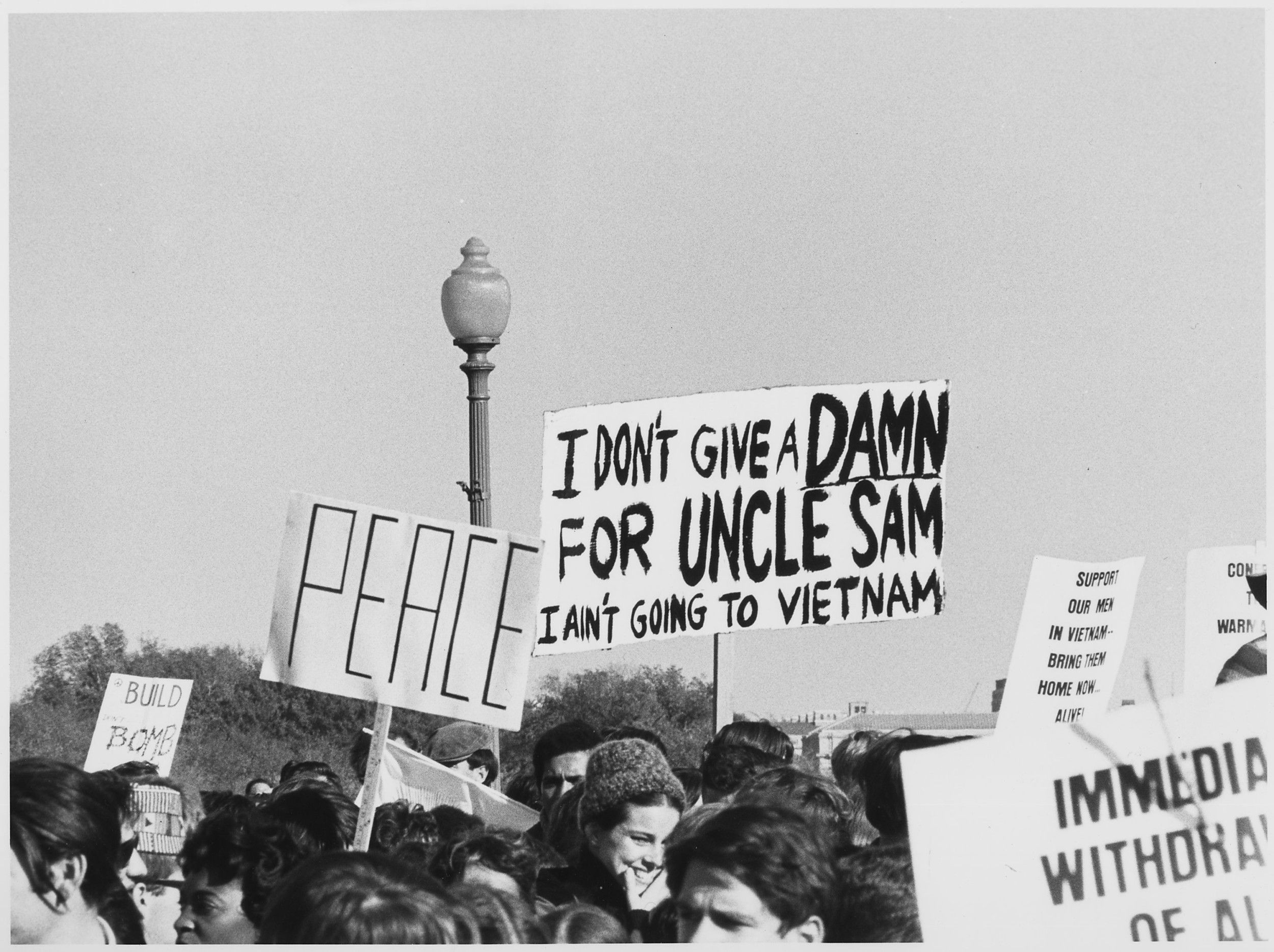

Freedom to Assemble

Pittsburgh Veterans for Peace at the March on the Pentagon

National Archives Identifier: 2803433

March on the Pentagon

Source: DocsTeach

The Lincoln Memorial was also the site of important events during the Vietnam War. On October 21, 1967, the March on the Pentagon, a massive protest organized by the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, began at the memorial. After participating in a rally there, about 50,000 people marched to the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia. Members of the 82nd Airborne Division came out to greet the protesters and keep them from entering the building. In response, activist Abbie Hoffman attempted to make the Pentagon turn orange and levitate using psychic energy. About 600 people, including the novelist Norman Mailer, were arrested. The protest was also the scene of the famous photo titled “Flower Power,” taken by photographer Bernie Boston for The Washington Star newspaper, of a young man named George Harris putting a carnation into the barrel of an M14 rifle a military policeman was holding.

One truly strange event took place at the memorial on May 9, 1971, when President Richard Nixon suddenly woke his valet, Manolo Sanchez, up at about 4 a.m. Nixon hadn’t been sleeping very well for several days—he had announced on April 30 that he was going to expand the Vietnam War into Cambodia, and almost immediately, protests had broken out on college campuses across the nation. The situation had deteriorated rapidly until finally, on Monday, May 4, at Kent State University in Ohio, National Guardsmen opened fire on peaceful student protesters, killing four and wounding nine.

In the five days since the shootings, protesters had poured into Washington for a march that was planned for the weekend. Many of them were camped out on the National Mall. Nixon was doing his best to control the situation. The previous night, he had held a press conference that ended at 10 p.m., and then he made phone calls for several hours. He slept for a while, and then he woke Sanchez up and asked him if he’d ever seen the Lincoln Memorial at night.

Sanchez said he had not. Nixon told him to get dressed because they were going down there. Sanchez, Nixon, a White House doctor, and a Secret Service detail all got into a limo and rode down to the memorial, where Nixon, in his customary suit and tie, got out and engaged in conversation with students who had come to Washington to protest the Vietnam War and the President’s policies.

Nixon recalls an impromptu meeting with student protestors at the Lincoln Memorial

To listen: click link above to open, then select the 2nd red box (10 min, audio only)

Source: Nixon Library

According to memoranda he recorded after he returned to the White House, Nixon spoke to the students for several moments on subjects ranging from college football to the one they were really interested in, the Vietnam War. He stayed at the memorial until the sun began to rise, at which point he went back down the steps to his limo.

Not surprisingly, other sources have reported this early morning meeting rather differently. Some of the students Nixon spoke with were skeptical of his explanations of his war policy, and others described his conversation as rambling and disjointed. White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman reportedly was concerned about Nixon’s state of mind during this period because, due to all the uproar over the escalation of the war and the shootings at Kent State, the President hadn’t slept for days.

Anti-War Demonstrators Storm Pentagon (1 min 43 sec)

Universal Newsreel Volume 40, Release 86, 10/24/1967

The French Statue

Untitled rendering by Henry Bacon

Lincoln statue installation

National Archives Identifier: 596194

The majestic statue Abraham Lincoln that inhabits the central chamber of the Lincoln Memorial was designed by the American sculptor Daniel Chester French (1850–1931). Born in New Hampshire to lawyer Henry Flagg French and Anne Richardson and raised in Concord, Massachusetts, French studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and in Florence, Italy, before returning to the United States. His first notable commission, The Minute Man, was commissioned by the city of Concord, Massachusetts.

The Lincoln Memorial Commission selected French to sculpt the statue of Lincoln for the memorial in 1914. He and architect Henry Bacon decided that a seated figure would be most appropriate, so French worked for about two years on clay and plaster models at his Chesterwood Studio in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. When the design for the sculpture was finalized, the Piccirilli brothers, who had worked with French for many years, were hired to do the actual carving, although French applied the finishing touches to the sculpture in the brothers’ New York studio. The sculpture is carved from twenty-eight blocks of marble quarried in Georgia. It was then shipped to Washington and assembled on site. It is truly monumental, weighing 170 tons and standing 30 feet high. The figure of Lincoln is 19 feet high, including the armchair and footrest.

Behind the statue, an epitaph by Royal Cortissoz, an art critic for the New York Herald Tribune, is carved into the wall: “In this temple as in the hearts of the people for whom he saved the union the memory of Abraham Lincoln is enshrined forever.”

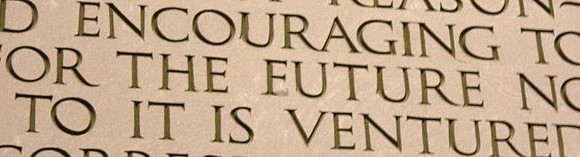

“WITH HIGH HOPE FOR THE EUTURE”

If you are looking at the Second Inaugural Address on the Lincoln Memorial wall and you think the “f” in the line “With high hope for the future” looks a little odd, you’re right—it was originally carved as an “e.” Carving the whole panel all over again would have been very expensive, so the bottom line of the “e” was puttied out. But if you look closely, you can tell it was fixed.

Can you spot the correction?

Pamphlet of Lincoln Speeches, see page 20

National Archives Identifier: 6782976