If You Build It

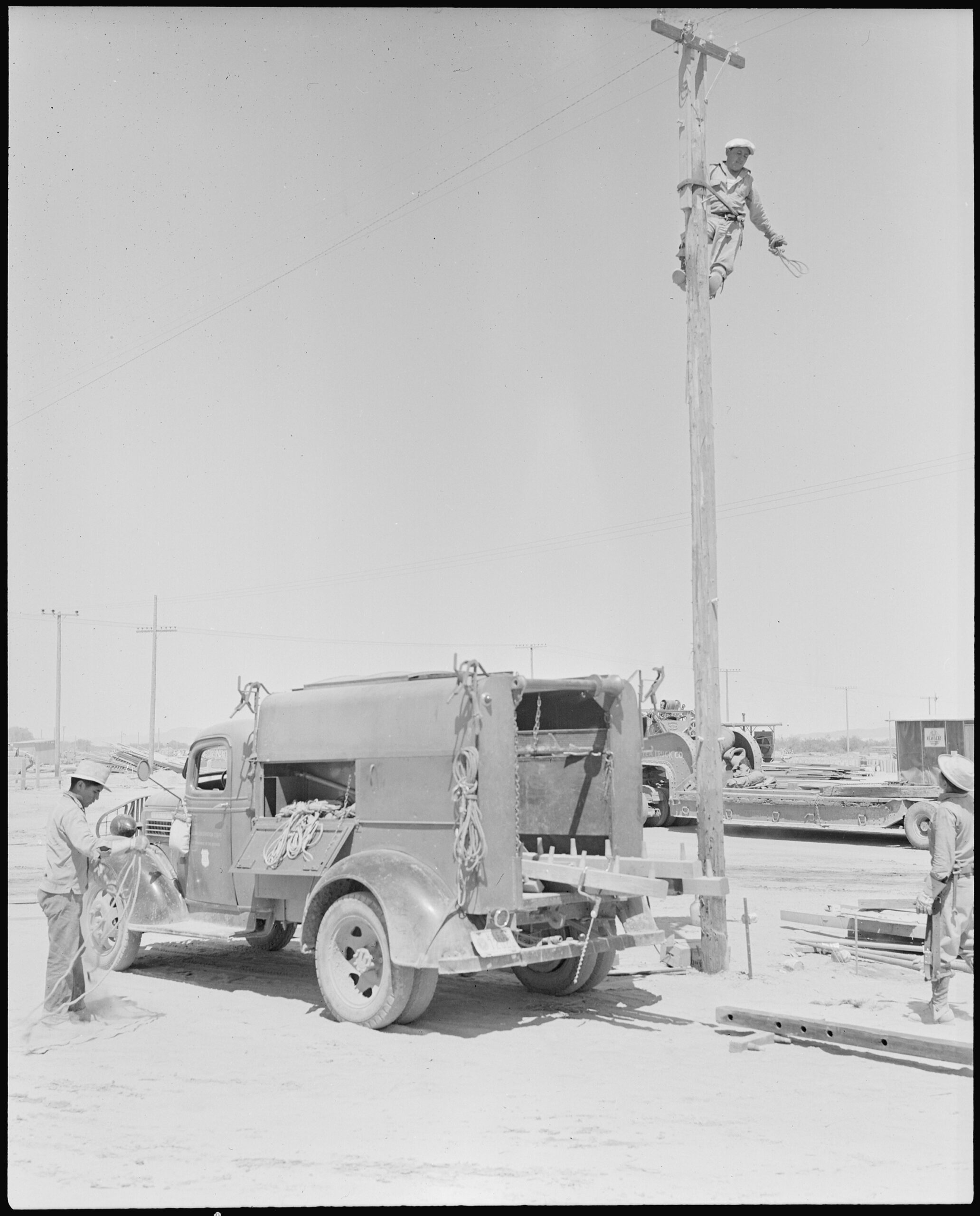

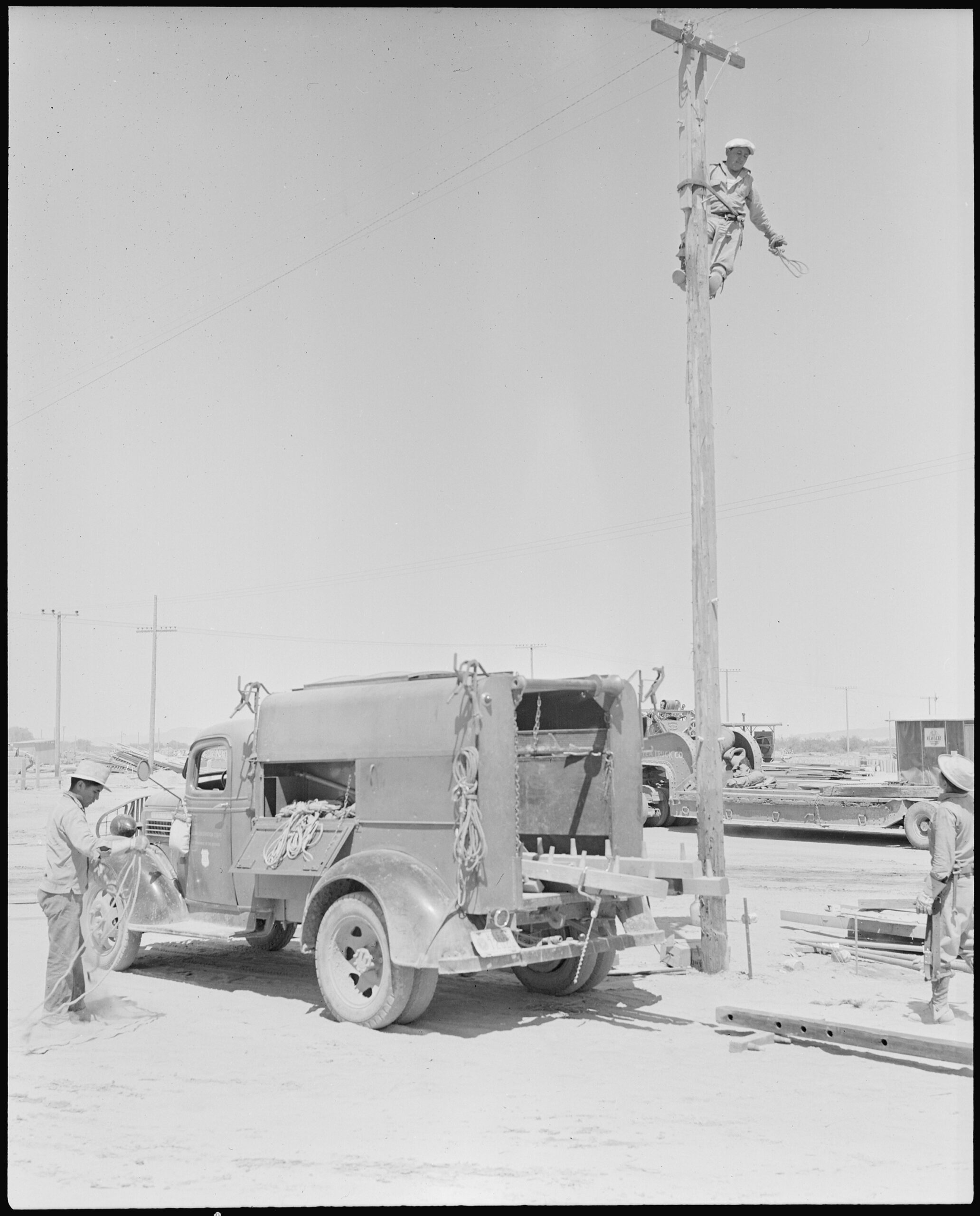

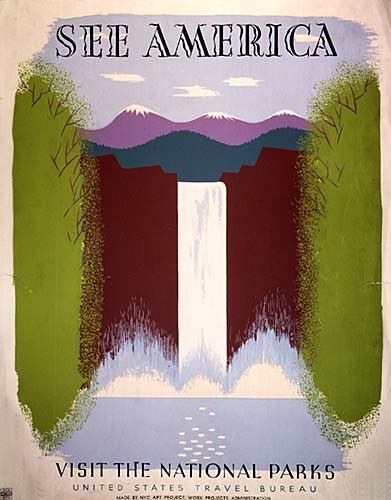

Infrastructure has always been about connections. From the transcontinental railroad to the interstate highway system, the federal government has a long history of investing in people and public works. As technology has advanced, our definition has evolved and now includes modernizing power grids and high-speed internet.

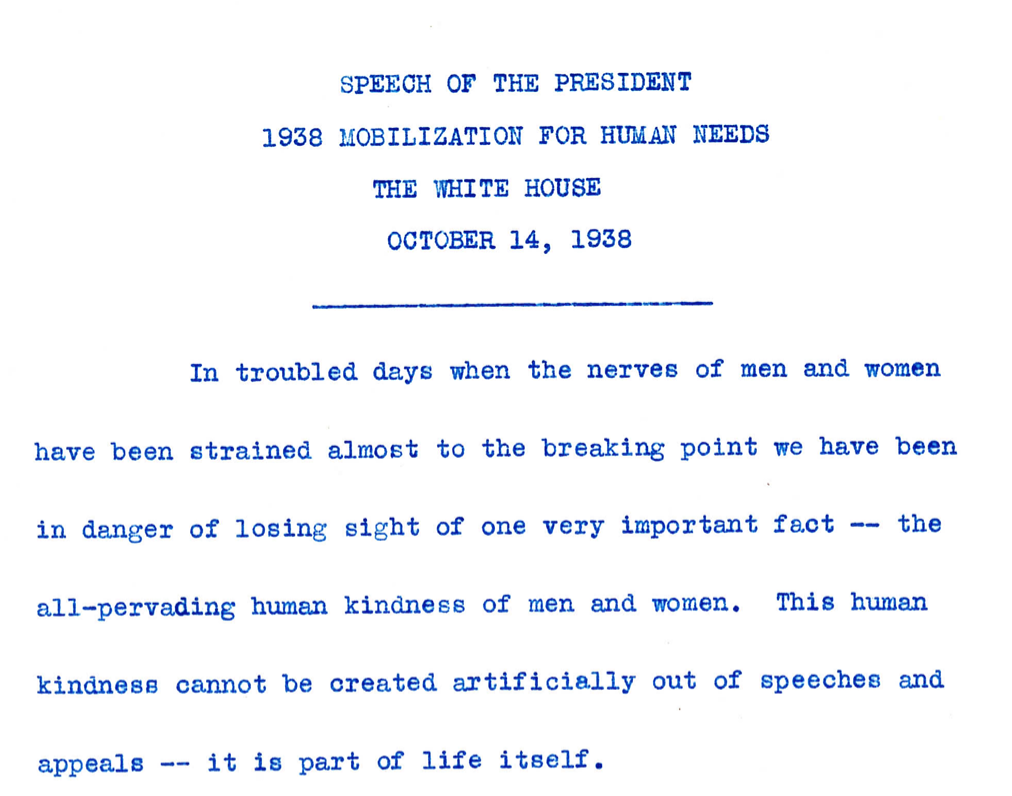

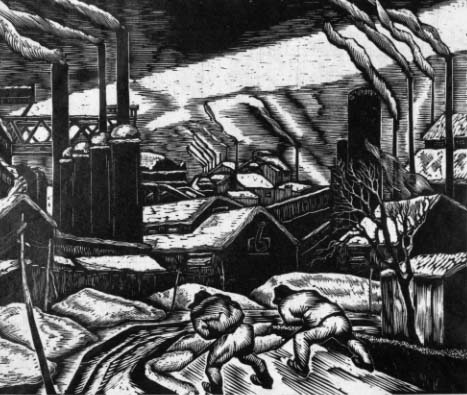

The Great Depression was a cascading crisis that started with the economy and grew to have devastating impacts on all aspects of society. FDR’s vision to bring the country out of the Depression was to invest in both our infrastructure and each other.

This week, we’re highlighting the records of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). These groundbreaking agencies put Americans to work rebuilding traditional infrastructure like roads and bridges. As they did that, they worked in tandem to expand new and less traditional infrastructure: planting trees, employing artists, and providing childcare. These stories just scratch the surface of the massive holdings related to the CCC and WPA in the Archives. Grab a shovel and dig in.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

We’re All Connected

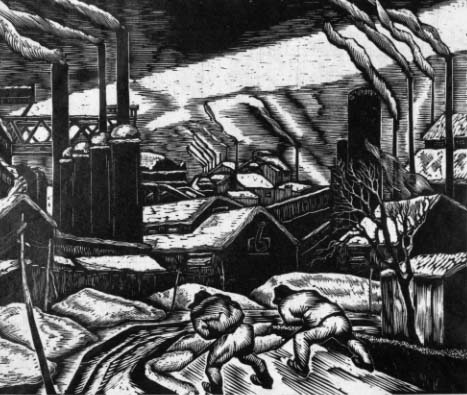

In 1933, the United States was in dire straits. The Great Depression, which began with the Stock Market Crash in 1929, reached its worst point that year, when nearly half of the banks in the country failed and fifteen million people were out of work. On the southern plains, people and their livestock were dying in a severe drought. The desperate conditions drove the survivors out of the Dust Bowl to cities in the north and northeast and the West Coast in search of work.

In the face of all this fear and desperation, newly elected President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was a bulwark of calm and comfort to his people. In his inaugural address on March 4, 1933, Roosevelt declared that he would respond to the “dark realities of the moment” and would “wage a war against the emergency” just as though “we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.”

Fireside Chat 1

Source: FDR Library blog

Roosevelt wasted no time in fulfilling his promises. By March 9, he had pushed the Emergency Banking Act, which closed insolvent banks and reorganized the rest of the banking system, through Congress. In his first one hundred days in office, he persuaded Congress to repeal Prohibition and to pass, among other important legislation, the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the Tennessee Valley Authority Act, the National Industrial Recovery Act, the Glass-Steagall Act, and the Home Owners’ Loan Act. (Incidentally, his success is the origin of the goal new Presidents now set for themselves to accomplish as much as possible during their first one hundred days in office.)

Despite these successes, homelessness and high unemployment persisted, so FDR set out to solve those problems with renewed energy. On April 5, 1933, by executive order, he created the Civilian Conservative Corps (CCC), a program designed to put unmarried, unemployed young men to work on environmental and infrastructure projects across the United States.

Between 1933 and 1942, nearly three million young men between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five worked for the CCC for a minimum of six months each. Among them were young, unskilled men from families on government assistance, World War I veterans, Native Americans, and African Americans. Enrolled in the corps by the U.S. Army and then transported to what eventually grew to 2,900 camps across the U.S., they were paid $30 per month, of which they were required to send at least $22 home to their families. Furthermore, nearly 60,000 young men learned to read and write while they served in the CCC.

Roosevelt’s Great Hurricane Speech

Source: FDR Library blog

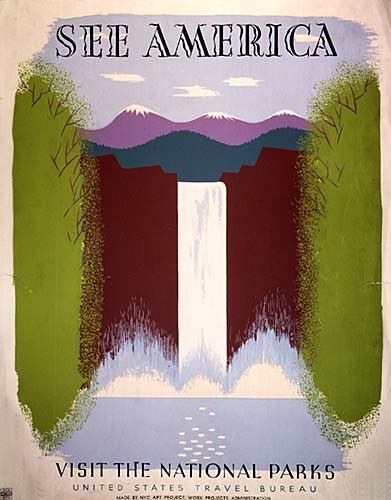

The National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Departments of Agriculture and Interior directed the work of the CCC employees, who planted more than three billion trees and built shelters, bridges, campgrounds, and trails in more than 800 national and state parks all across the country. The corpsmen worked an eight-hour day, which included transportation to and from the work sites. Besides the sleeping quarters and mess halls, the camps also had recreational facilities for baseball, football, and basketball. Eventually, educational programs were offered in the evenings as well.

The CCC was a great success, but it was not without its detractors. Leaders of trade unions were critical of the CCC because so many union members were out of work at the time. To placate the unions, Roosevelt appointed Robert Fechner, vice president of the International Association of Machinists, to be the first director of the CCC. He proved to be an effective leader.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

How to search CCC records

(57 minutes 10 seconds)

Source: NARA YouTube channel

Everything’s Covered

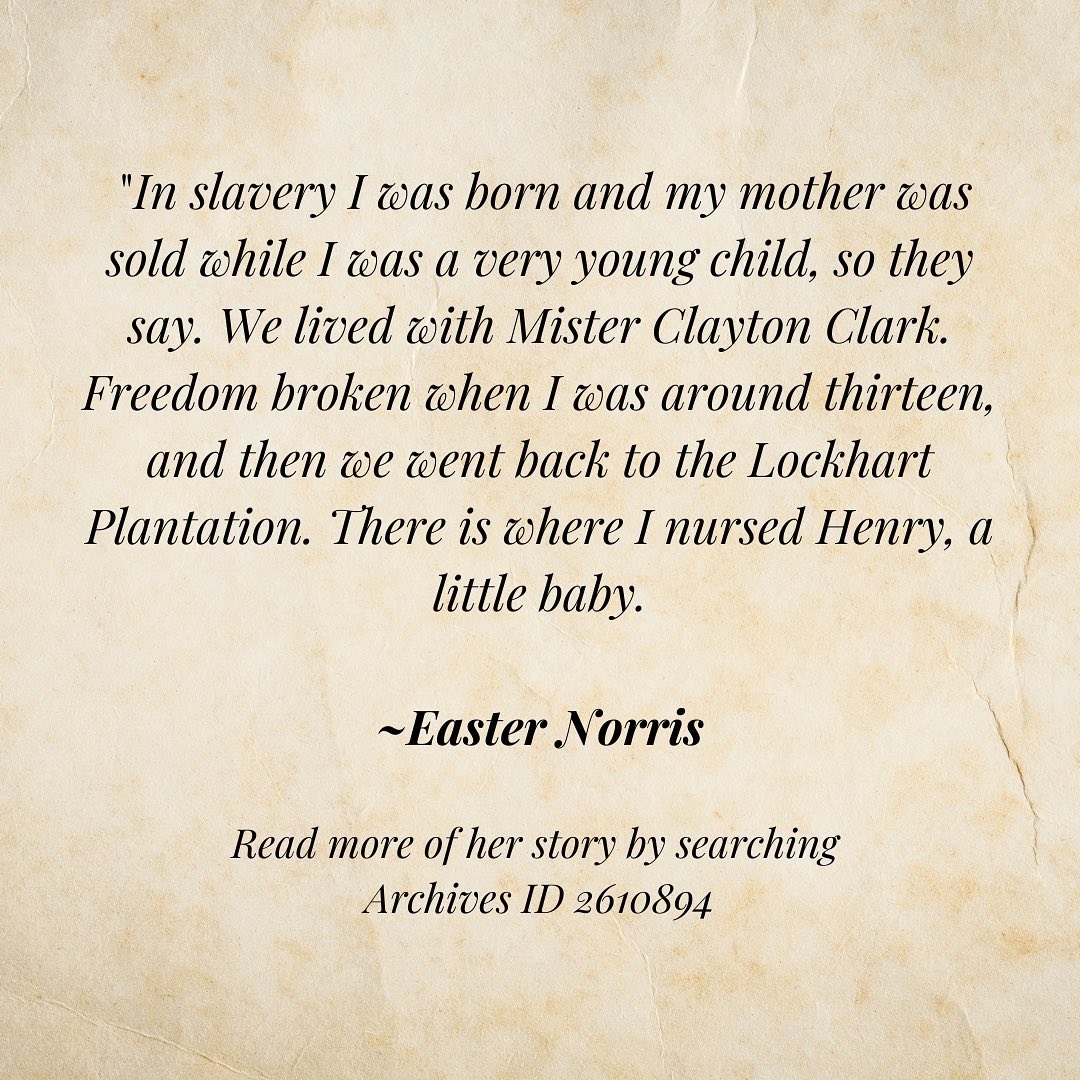

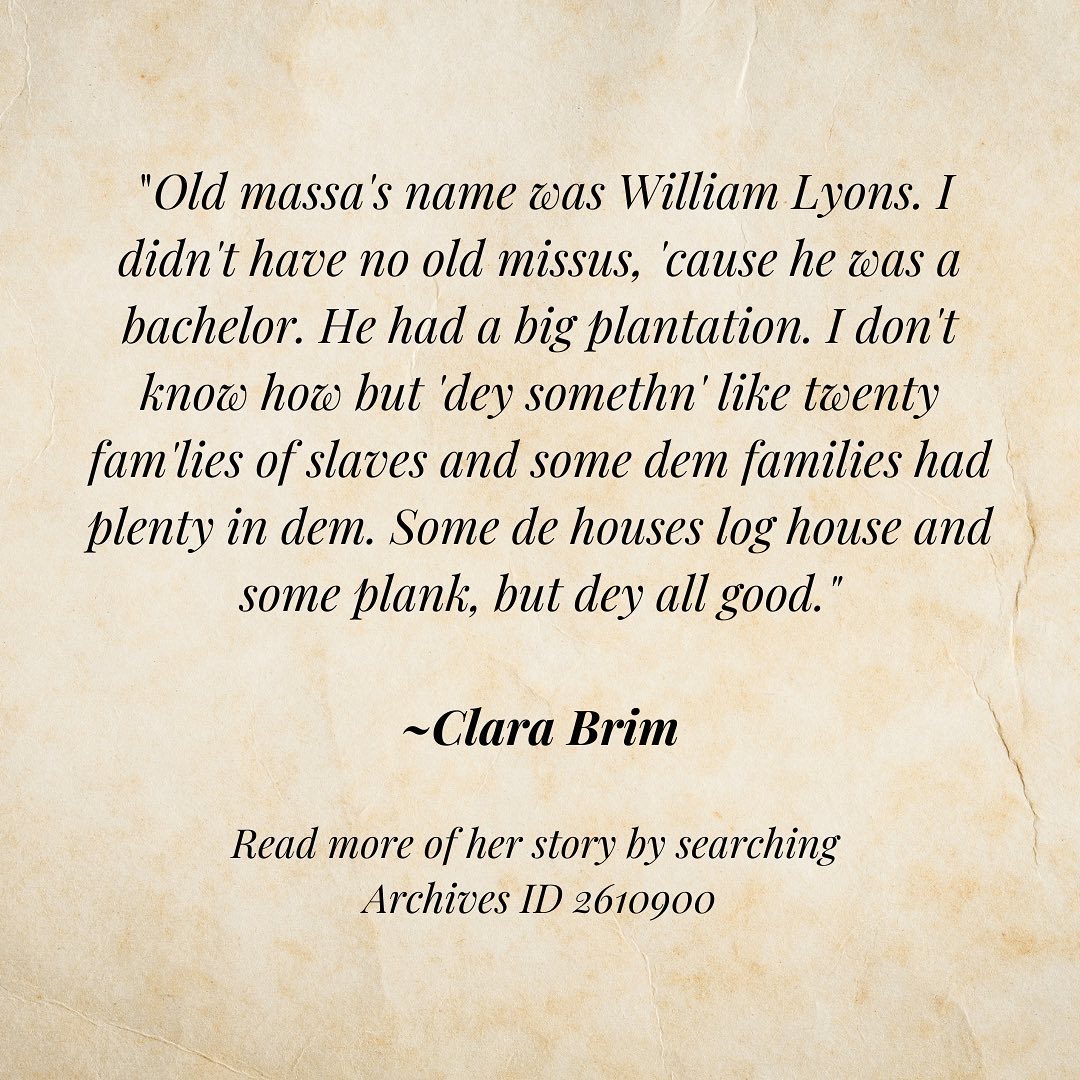

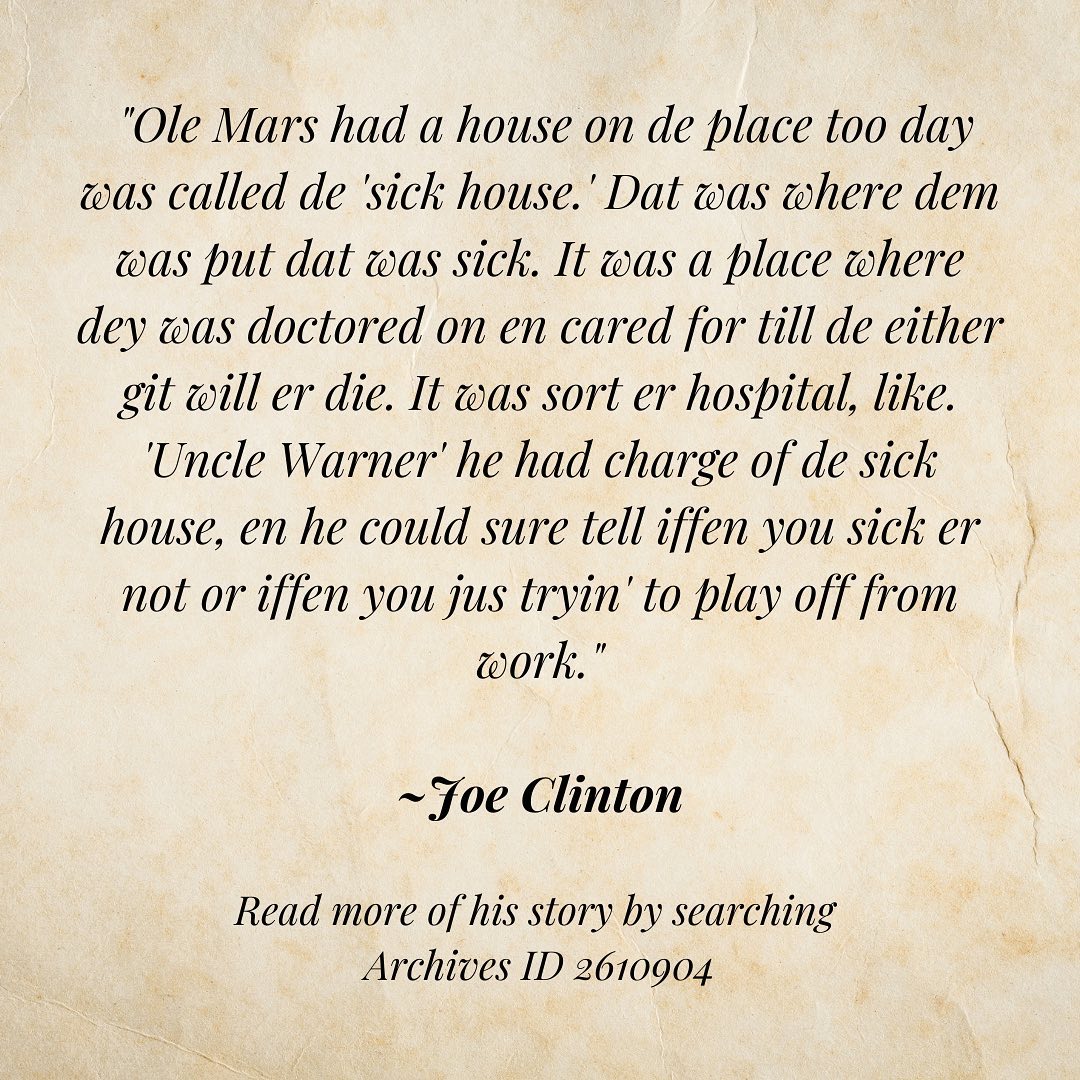

Read oral histories from formerly enslaved people

Slave Narrative Files

Source: National Archives Catalog

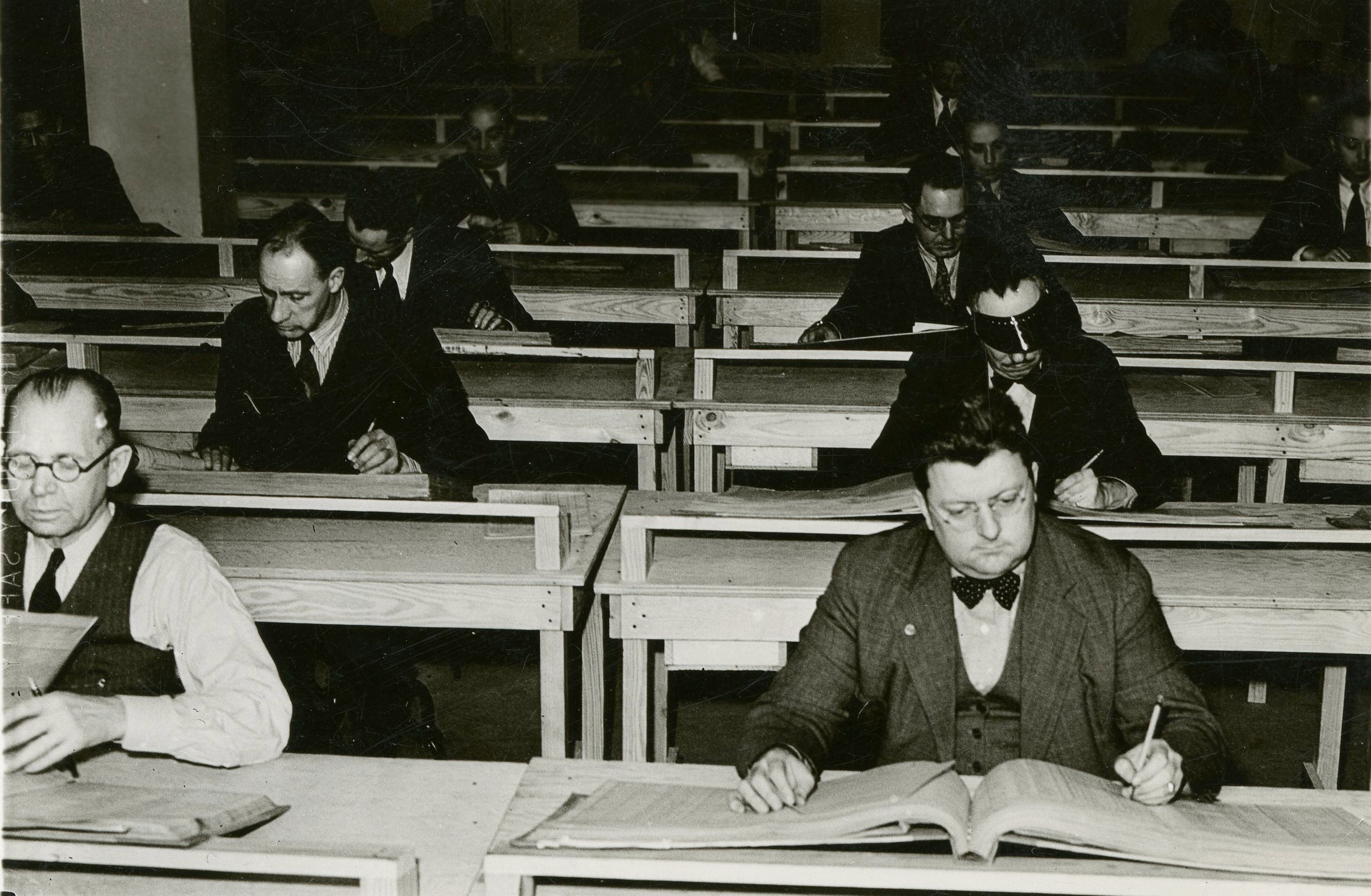

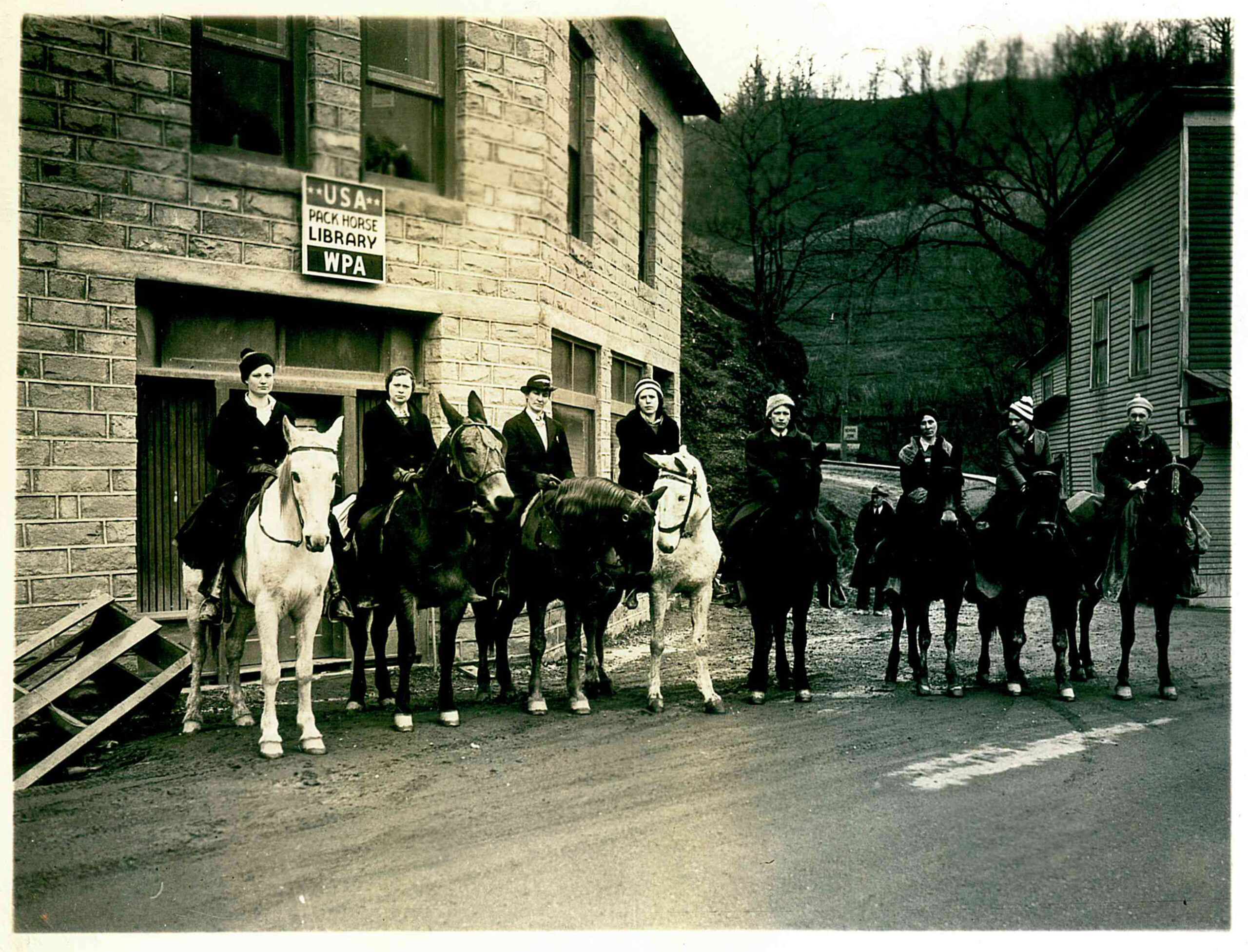

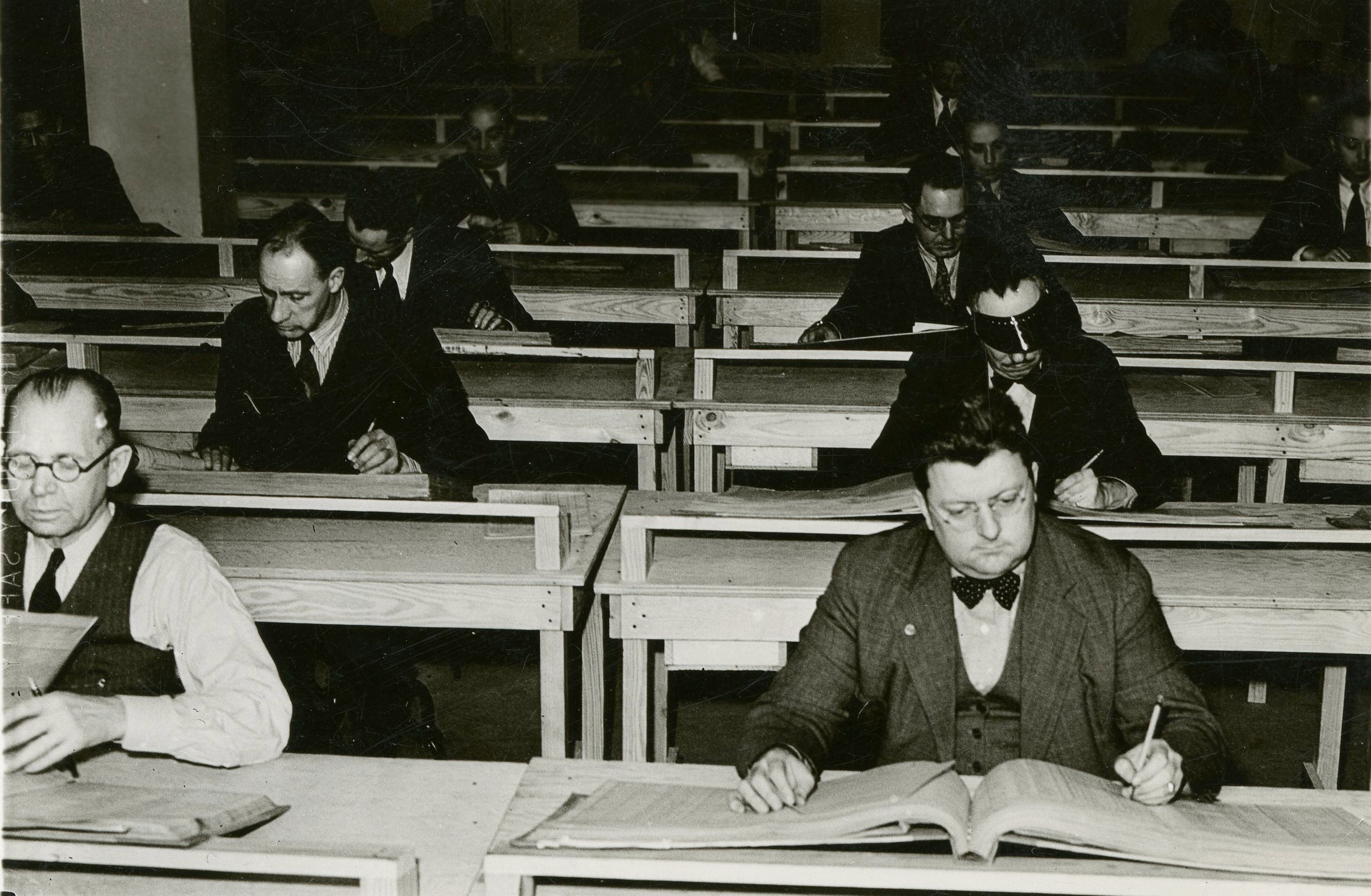

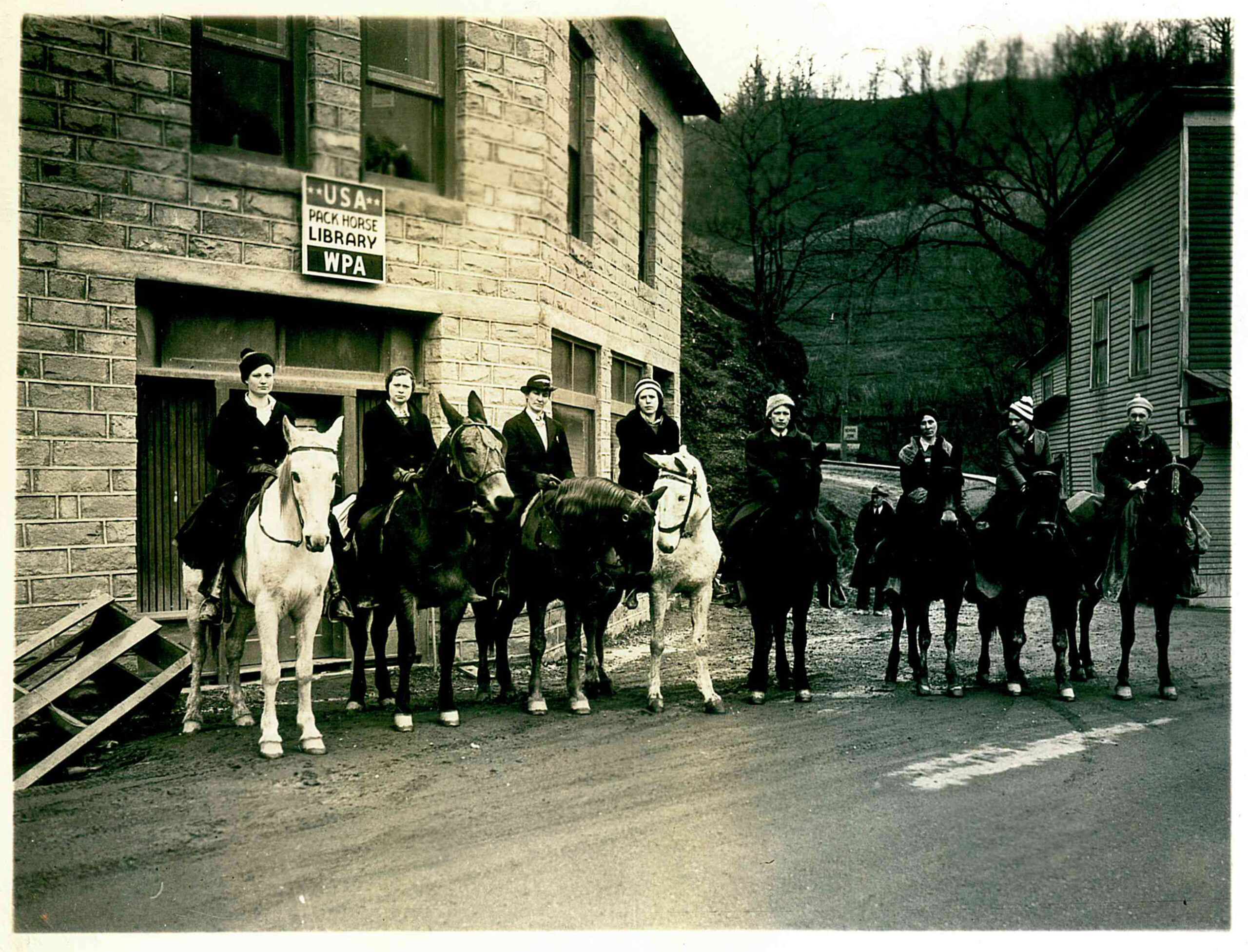

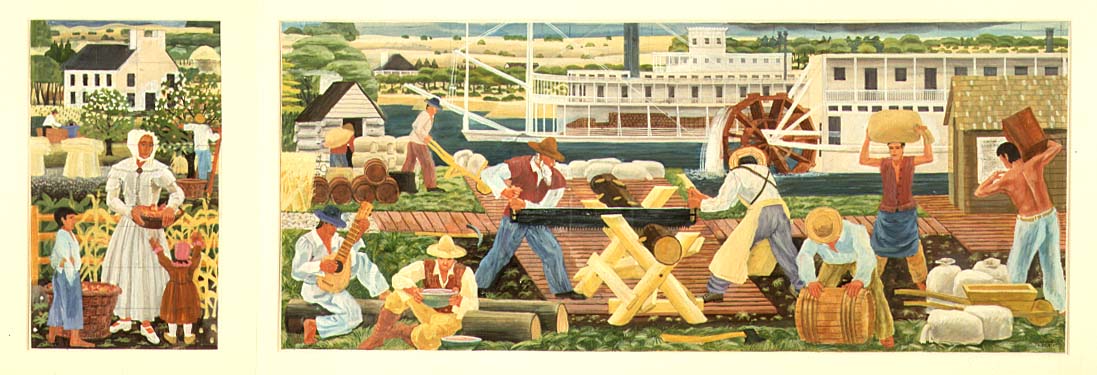

The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was a program FDR established by executive order in what he called the Second New Deal, a group of programs he initiated to combat persistent unemployment and homelessness. Established on May 6, 1935, the WPA put millions of unemployed people to work on public projects that included building roads, schools, parks, and bridges.

A subprogram, Federal Project Number One, which is probably the best-known, was further divided into five projects: the Federal Art Project, the Federal Writers’ Project, the Historical Records Survey, the Federal Theatre Project, and the Federal Music Project. Under these umbrella projects, the WPA employed actors, artists, writers, musicians, and other professionals in arts, drama, and media projects. Eleanor Roosevelt was instrumental in supporting Federal Project Number One and protecting it from critics who believed that programs that support the arts were a waste of public funds (some things never change).

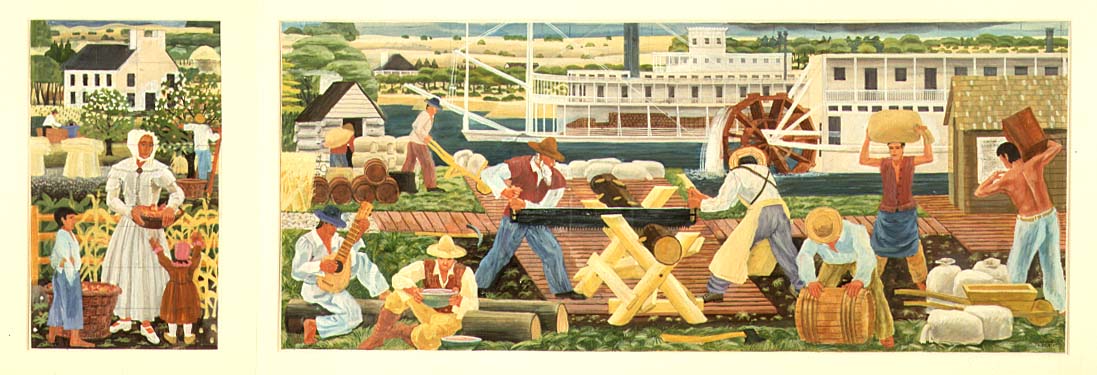

The historical and cultural significance of these endeavors to the nation can hardly be overstated. The Federal Art Project funded art projects throughout the U.S. It supported established artists and gave an important boost to the careers of many who were just getting started. The Federal Writers’ Project employed writers, of course, but also editors, historians, researchers, and librarians, who produced the American Guide Series, the Slave Narrative Collection, children’s books, and local histories. The Historical Records Survey, which originally was part of the Federal Writers’ Project, indexed historically significant records in local, county, and state archives. The Federal Theatre Project employed thousands of actors and theater professionals who produced theatrical performances nationwide in theaters, parks, schools, churches, clubs, and factories, many in small towns that had never hosted professional productions before. The Federal Music Project employed professional musicians to perform and music copyists and binders to prepare musical scores, offered music lessons to adults and children, and encouraged music appreciation among audiences of all ages.

WPA films: relief efforts in different states were captured on film.

Is yours here?

Source: National Archives Catalog

Although it was a federal program, the WPA cooperated with state and local governments to get unemployed people off relief and working again. The goal was to employ one breadwinner per household, so both men and women were employed.

The beginning of World War II spelled the end of both the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration. As the demand for soldiers skyrocketed and the war industries also needed more hands to produce munitions, tanks, ships, and aircraft, Congress stopped funding the CCC and the WPA and sent those monies to the Armed Forces instead. That said, many of those who had worked for the CCC and the WPA had learned valuable skills and work ethics that served them well when they joined the military to fight in World War II.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

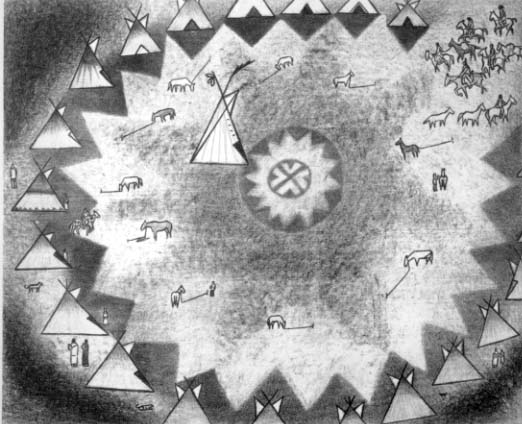

Lines Still Drawn

Despite their obvious successes, the CCC and the WPA had some serious issues, most of which were common to their times. As it was in mainstream U.S. society in the 1930s, racial discrimination was baked into both organizations. African American and Native American CCC members served in segregated units because the U.S. Supreme Court didn’t consider segregation to be discrimination in the 1930s. Native American corpsmen worked exclusively on reservations.

Women were not allowed to join the CCC at all. Troubled by this, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt lobbied to establish camps for unemployed women, many of whom were reduced to standing in breadlines and sleeping in subway stations or outdoors. She faced an uphill battle because many men in her husband’s administration, to say nothing of those in Congress, thought she was proposing to send women on an all-expense-paid vacation in the middle of a national depression. Nevertheless, FDR established the camps by presidential order in 1933. On June 10, 1933, Camp TERA (Temporary Emergency Relief Assistance) opened at Bear Mountain State Park in New York. Eleanor Roosevelt’s camps were quickly dubbed “She-She-She” by her critics, who thought a woman’s place was in the home, not in the great outdoors.

BBy 1936, there were ninety camps throughout the country. The attendees studied housekeeping, economics, clerical skills, English, and forestry. However, ongoing criticism from those in high places, including suspicions that the campers were communists, and lack of funding plagued the camps from the beginning. The camps closed on October 1, 1937.

In contrast, the WPA did employ women, but only those who were the sole supporters of their families, such as widows or women with disabled husbands. Only about seven percent of the WPA’s employees were female, and they were employed in traditionally female jobs such as sewing, cooking, canning, gardening, and clerical work. African Americans made up about 15 percent of the WPA workforce.

(15 minutes 52 seconds)

National Archives Identifier: 12322

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

Going Green

The Civilian Conservation Corps was a tree-planting juggernaut—by the time it was formally concluded at the end of the 1942 fiscal year, the corpsmen had planted more than three billion trees all across the country. Consequently, and not surprisingly, the CCC has become the model for modern conservation organizations. Many other programs, including the Student Conservation Association, Sea Ranger Service, Conservation Legacy, and many state-based conservation organizations, have taken their inspiration from the Civilian Conservation Corps.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

FDR and the Dust Bowl

(4 minutes 16 seconds)

Source: FDR Library YouTube channel

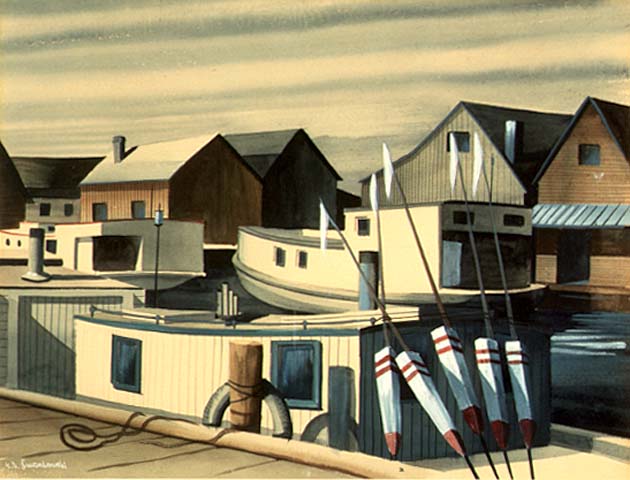

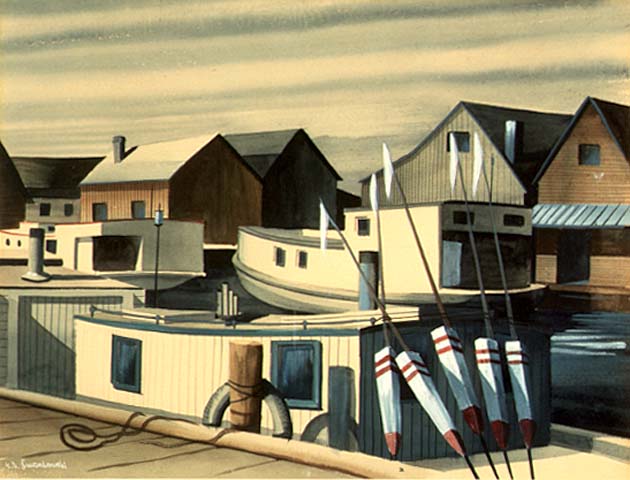

The Art of Rebuilding

The list of artists and writers who worked for the Works Progress Administration is truly astonishing. The Farm Security Administration’s Resettlement Administration sent photographers out into the field to document its work from 1937 to 1942. They included Dorothea Lange, Gordon Parks, Marion Post Wolcott, Edward and Louise Rosskam, Marjory Collins, Arthur Rothstein, Walker Evans, John Collier, Russell Lee, Jack Delano, and Berenice Abbott.

Abstract Expressionists who worked for the WPA before finding success later in the New York art scene included Jackson Pollack and his wife and fellow Abstract Expressionist Lee Krasner, Ad Reinhardt, James Brooks, Mark Rothko, Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning, and Louise Nevelson.

A quarter of a million African American artists eventually worked for the WPA. They included Aaron Douglas, Augusta Savage, Dox Thrash, Georgette Seabrooke, Elba Lightfoot, Eldzier Cortor, and Adrian Troy.

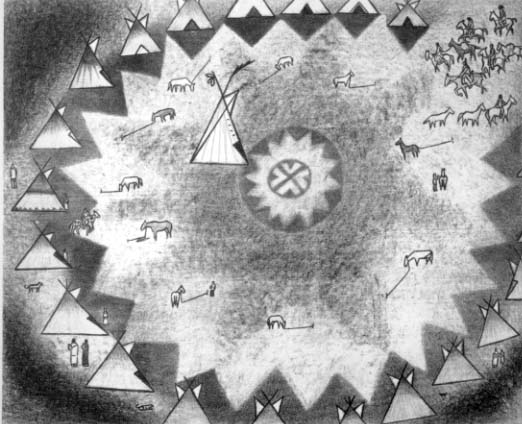

The WPA also employed many Native American artists to work on projects for the Department of the Interior. They included Julius Twohy, Gerald Nailor, Hoke Denetsosie, Allan House, Velino Shije Herrera, and Woodrow Crumbo.

Renowned writers who worked for the WPA include Conrad Aiken, Saul Bellow, John Cheever, Ralph Ellison, Stetson Kennedy, Studs Terkel, Margaret Walker, Dorothy West, and Frank Yerby.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above