Go West

Even as Europeans established East Coast communities in North America, they looked west. Many struck out on their own, establishing farms and towns, but often at the expense of the American Indian nations and tribes for whom these lands were home for generations.

The Louisiana Purchase and the U.S.-Mexican War both expanded the boundaries of the nation westward. Then, in 1862, at the height of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act. It provided that any adult citizen or future citizen of the United States could claim 160 acres of surveyed government land. The aim of the Homestead Act was to give small farmers the opportunity to acquire their own land. Literally millions of individuals filed claims and set about “proving up” to secure title to them. Immigrants just off ships, single women, farmers who had long worked for other farmers, and formerly enslaved people all went west to cultivate the land with the hope of a new and prosperous life.

While many stories of our nation’s expansion are inspiring and adventurous, it was not without hardships and injustices. This week, we journey into the depths of the Archives to bring you images and stories of the trek west.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

The Disinherited

From the beginning of European settlement in what became the United States, the new settlers were in conflict with the American Indian tribes and nations who occupied the land. Starting just before the end of the Civil War, several dramatic events in the western United States climaxed in the removal of western American Indian tribes and nations to reservations and the dividing up and sale of their lands to settlers. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, the discovery of gold in the Black Hills of South Dakota, General George Armstrong Custer’s defeat at the battle of the Little Bighorn, the creation of the reservation system, and the Dawes Act of 1887 all contributed to the disenfranchisement and degradation of western American Indian tribes and nations.

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

Many historians consider the Dawes Act of 1887 one of the most catastrophic blows to Native American sovereignty. The act allowed the federal government to sell off any “excess lands” to anyone who was interested in buying it, regardless of whether or not it was the home to existing American Indian nations.

In 1894, the Hopi Tribe who lived in the Moqui villages in Arizona, petitioned Washington to give them title to their land instead of dividing it up into individual parcels. The petition was signed by all the Chiefs and headmen of the Tribe and inscribed with symbols of every family living in the villages. The petition was an attempt to protect the Hopi Tribe way of life from outside settlers. As was not uncommon, the federal government did not formally respond to the petition.

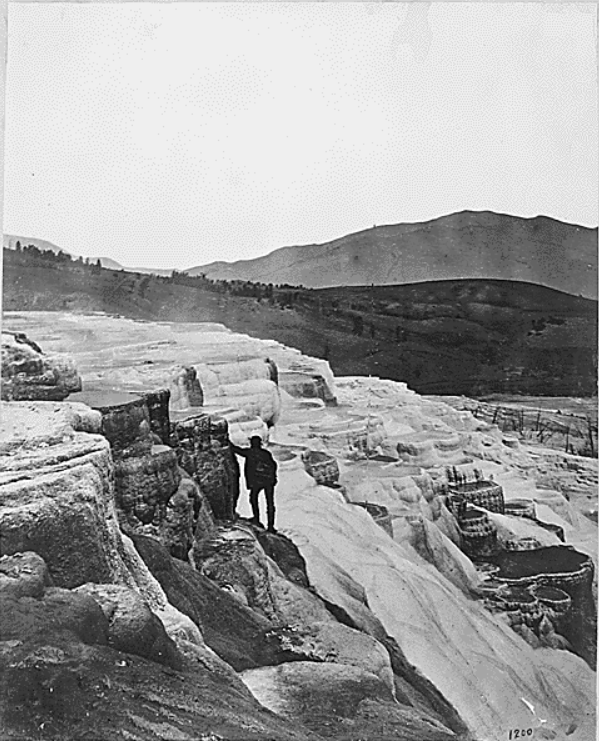

The Hayden Survey

In the late 19th century, the U.S. government sponsored four major surveys of western land. On one of the first such surveys, Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, a geologist, led a group of naturalists, scientists and artists to explore the areas around what became Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming and Montana in 1870.

National Archives Identifier: 516891

Source: NARA’s Prologue Magazine

The artist Thomas Moran and the photographer William Henry Jackson were along to document the group’s experiences. Published in 1871 in the survey’s official report, the images they created went a long way toward persuading Congress to designate Yellowstone the U.S. first national park.

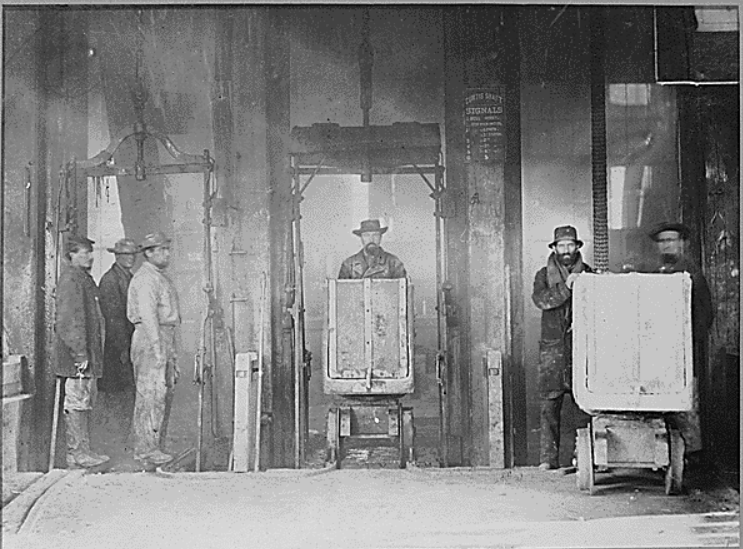

The Search for Gold

James W. Marshall’s discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, California in 1849 set off a tsunami of people racing to California. Seekers of riches came from all over the world to dig for their fortunes there. One result of the Gold Rush was that California became a state in 1850, the farthest-flung state in the union.

National Archives Identifier: 517164

Other rushes for gold and other metals have also helped shape the American West. Discoveries in Colorado, Montana, Idaho, Oregon, New Mexico, and Alaska fired the public’s imagination and sent thousands west to seek their fortunes. The Klondike Gold Rush (1896-1899) in Yukon Territory was one of the last great rushes for mineral riches.

All over the country, tiny towns and settlements sprang up.

National Archives Identifier: 298078

Miners lived in tents and worked their own claims, which were often subject to being hijacked by other miners. Living conditions were harsh, and provisions were startlingly expensive.

It’s the Journey

A famous Chinese proverb advises us that a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. In the early days of westward expansion, from the mid-19th century on, many people literally walked from where they lived to where they wanted to be, sometimes behind ox- and horse-drawn wagons in wagon trains, sometimes pushing all their belongings in a handcart. They also travelled on horseback, and eventually by stage coach and transcontinental railroad. Some even took passage on boats that sailed up rivers to western towns or from southern states around Cape Horn at the southernmost tip of South America to reach the West Coast.

Did any of your ancestors head west by any of these methods? Do you know any of their stories?

National Archives Identifier: 520085 |

National Archives Identifier: 530892 |

National Archives Identifier: 530883 |

Game Night

National Archives Identifier: 530986

The first building erected in a new western town was often a land office (if the town was a mining town), followed by a general store. Thereafter followed churches, breweries, and saloons.

Saloons were the centers of the communities, offering food, drink, and camaraderie. Many patrons of saloons played games there—poker, of course, but also other card games, dice games, and faro, a card game that was wildly popular. After his stint as a lawman in Dodge City, Kansas, Wyatt Earp joined his brothers in opening a saloon in Tombstone, Arizona, where he took up the job of faro dealer. Interestingly, the game did not offer the house a huge advantage, and cheating was widespread among both the players and the dealers.