Enemies to Lovers

Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy from Pride and Prejudice. Harry and Sally from When Harry Met Sally. Kate and Anthony from Bridgerton. The fact that there’s an enemies to lovers story for almost every generation means that first impressions aren’t always lasting. And if it’s true for romance, it’s also true for diplomacy.

Before we even became a nation, colonists were embroiled in a conflict with France. It was a war on such a great scale that the conflict on American soil–the confusingly named French and Indian War–was an offshoot of a much bigger war: the Seven Years’ War.

So how did we go from all-out war to the French helping us fight for our freedom and giving us one of the most iconic symbols of our nation? We’ve sifted through centuries of love notes in the Archives to find out…

In this issue

The gallant Frenchman Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, arrived in America when he was just shy of his 20th birthday…

Nothing says love like offering your beloved a great investment opportunity, right?…

Nicolas Sarkozy is such an admirer of the United States that he has been called “Sarko the American”: in response, he said he “loves his nickname”…

History Snack

The year is 2003. The setting is a North Carolina restaurant. The menu item is Freedom Fries. Wait what?…

Off to a Rough Start

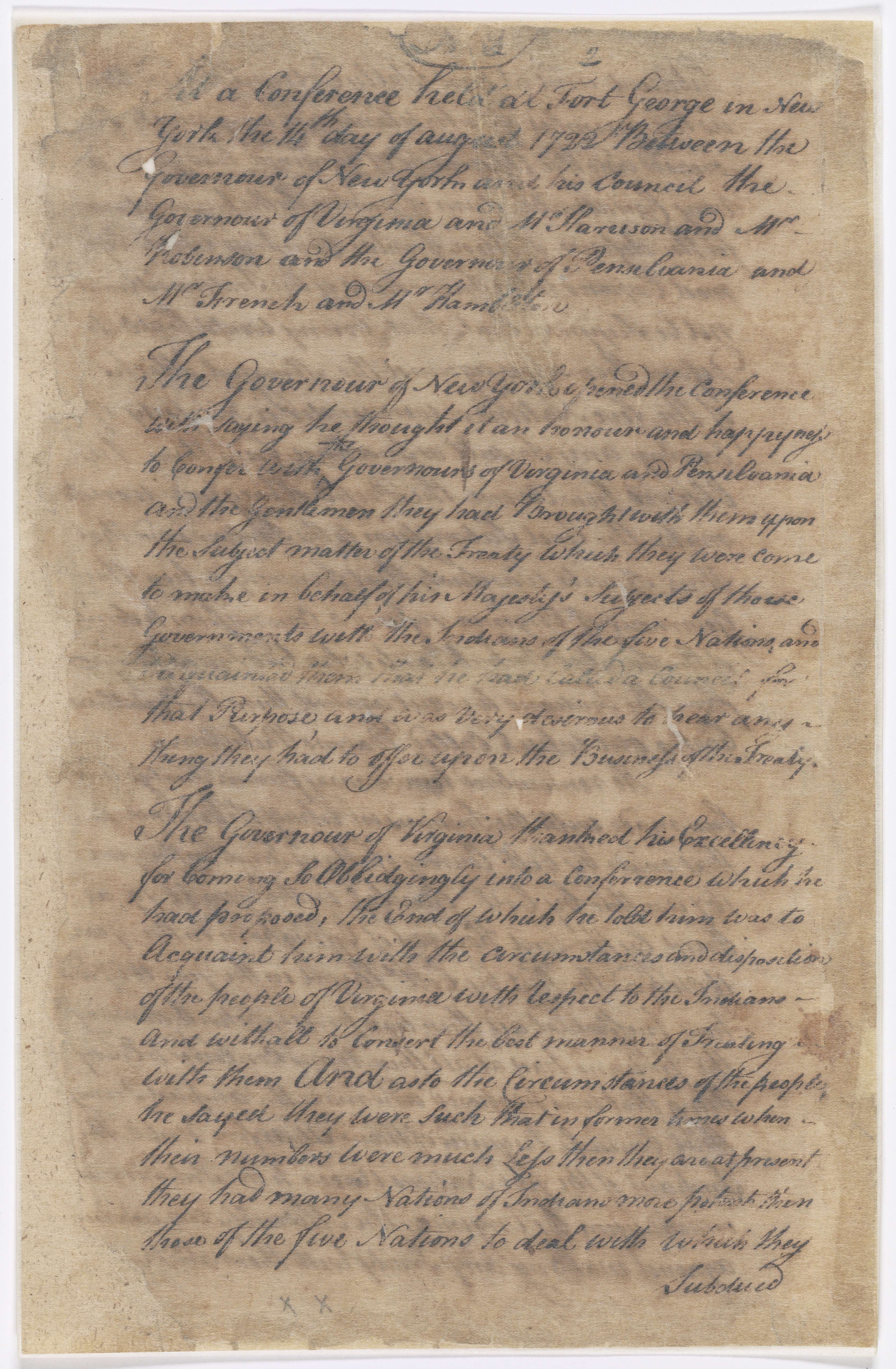

Treaty of Fort George — 1722: The Iroquois pledge to “cleve close” with the British but not completely rebuff the French

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

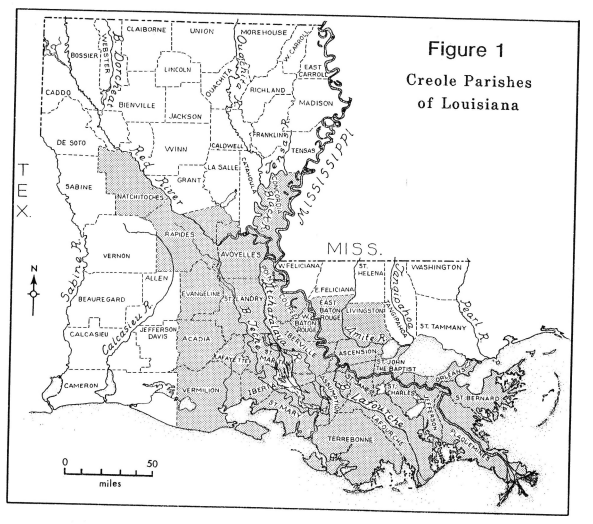

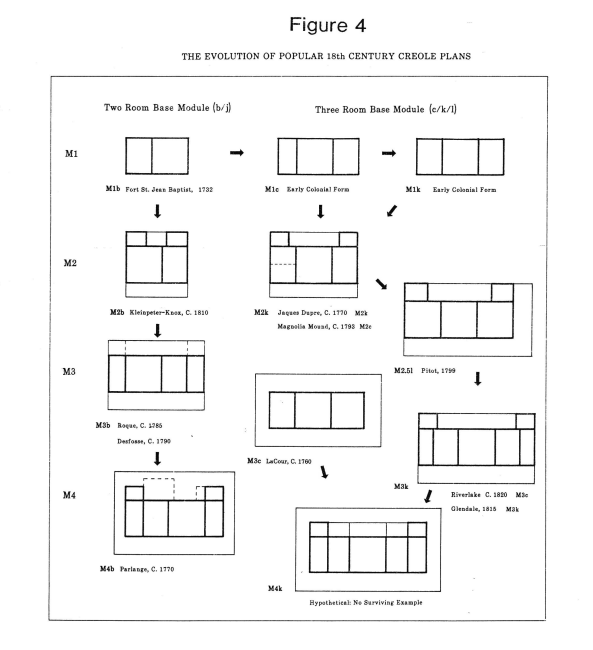

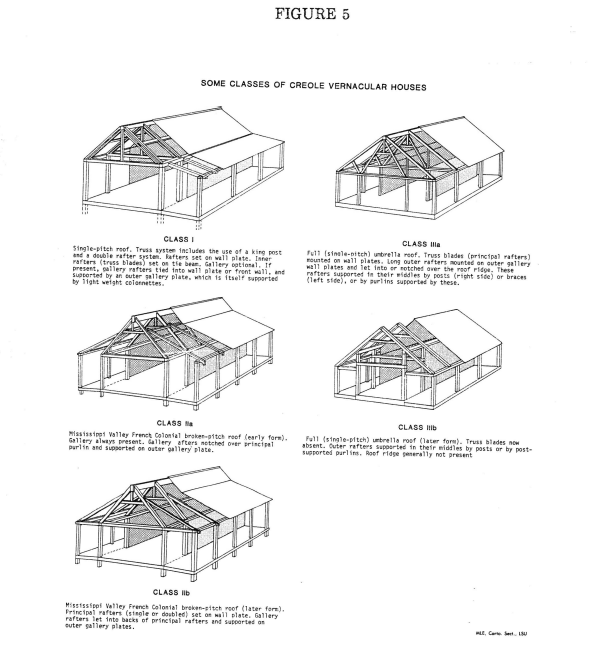

The love affair between France and the United States, which the two nations have been carrying on for more than 200 years now, got off to a rocky start, but that was all the fault of, shall we say, the parents. In the beginning, the colonies were, after all, British, and France was trying to establish its own empire on the North American continent at the same time that Britain was. France had founded its colonies, which it called “New France,” mostly in Canada and in parts of what are now the states of Maine, New York and Pennsylvania, and among the islands in the Caribbean. When France began expanding its empirical ambitions into the Ohio River Valley, Britain launched what became the Seven Years’ War, called the French and Indian War in North America. Fought on five continents, and actually lasting more than seven years, the conflict officially began in 1756, when Britain declared war on France.

Treaty of Albany Extracts — 1754: Solidified the relationship between the British and Iroquois

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

Despite the name of the war in North America, all American Indian tribes did not align themselves with the French. The Wabanaki Confederacy, whose peoples lived for the most part in New France, did fight mostly for the French, but the Iroquois Confederacy sided mostly with the British, and many other tribes took different sides, remained neutral or switched sides, as they deemed most beneficial to their people.

Military service agreement between Governor of Louisiana Louis Bilolouart and Chief Okana-State of the Cherokee nation for military service

National Archives Identifier: 6924937

Annotated map of British colonial America — 1775

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

After a series of battlefield losses in North America, including a notable one led by a young George Washington, the British finally defeated the French, and the war ended with the Treaty of Paris in February 1763. The treaty gave Britain possession of all of New France in Canada and what eventually became the United States. In addition, because Spain had sided with France, Britain received Florida, which had been a Spanish possession for almost exactly 200 years. In exchange, Britain returned to Spain control of Havana and Manila.

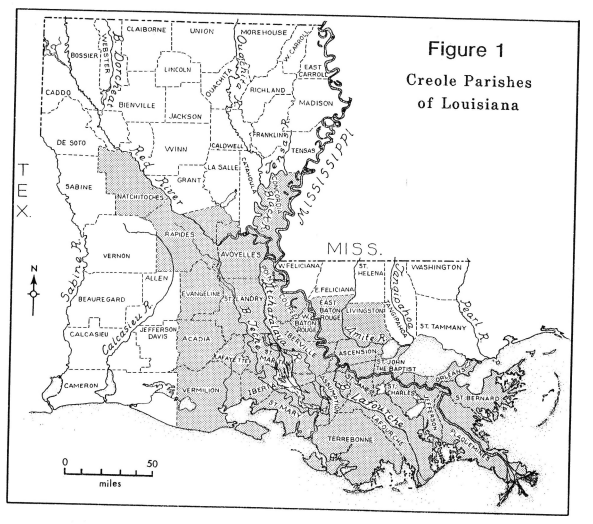

The NEW New France

The war had serious consequences for the Acadians, who lived in New France, including in parts of the continent that are now Maine. Early on in the conflict, the British were worried about the Acadians’ loyalty. Although the Acadians promised to remain neutral, the British didn’t believe them, and starting in 1755, they sent thousands of them packing.

Most of them returned to France or settled in the southern coastal American colonies of South Carolina or Georgia, but after about 1760, many of them began to return to the French-controlled colonies of Louisiana and some of the Caribbean islands. In Louisiana, their name, “Acadians,” was gradually changed to “Cajun,” and their French culture melded with Spanish, Native American and African American cultures to create one of the greatest of all American traditions, especially in and around New Orleans.

America’s Favorite Fighting Frenchman

Marquis de Lafayette bust

National Archives Identifier: 512941

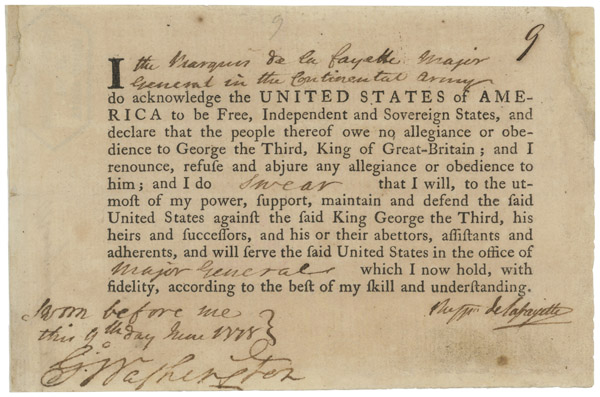

Smarting over its defeat in the Seven Years’ War and inspired by the democratic ideals of the Declaration of Independence, France sided with the fledgling nation during the American Revolution, first sending the Continental Army supplies in 1775. The gallant Frenchman Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, arrived in America when he was just shy of his 20th birthday and offered his services to George Washington and the Continental Army. Lafayette, as he became known to the colonists, had been born into a wealthy French family in 1757. Coming from a long line of soldiers who had served France’s royalty, Lafayette was formally educated in his family’s martial tradition. He and Washington took to one another immediately. Although the Continental Congress had commissioned Lafayette as a major general upon his arrival in Philadelphia in July 1777, Washington advised him that because of his foreign birth, Lafayette could not expect to command colonial troops. However, Washington, who had no children of his own, told the young man that he would gladly act as his “friend and father.” Lafayette became very much like a son to the older man, who appointed him to his staff.

Lafayette’s Oath of Allegiance to the US

Lafayette quickly overcame the seeming difficulty of his foreign birth by virtue of his humility and his military acumen. He was wounded at the Battle of the Brandywine, but he still managed to get the defeated Continental forces off the battlefield and to safety in good order before he submitted to treatment. He stayed with Washington and his troops at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-1778, and he served with distinction at the Battle of Rhode Island.

Hamilton letter to Lafayette before Yorktown

National Archives Identifier: 44276763

He then returned home to France, where he drummed up support for the colonists’ cause. At the urging of Benjamin Franklin, who had slipped into France in 1776 and had charmed the French court with his erudition and wit, and with Lafayette’s encouragement, France and the Continental Army then signed a Treaty of Alliance in 1778, under which agreement France sent troops, supplies and money to aid the colonists in their fight for independence. At that point, Britain declared war on France, which took place mostly on the high seas.

Letter from George Layfaette to the President acknowledging a receipt of Congress’s resolution honoring Marquis de Lafayette, and thanking the President and people of the US

National Archives Identifier: 149283042

If anyone ever doubts the sincerity of France’s commitment to the U.S.’ cause, we have just one word for you: Yorktown. When Lafayette returned to America in 1780, he was appointed a commander in the Continental Army. In 1781, he and his troops held the British General Charles Cornwallis at bay until the combined Continental and French forces could lay siege to the British forces at Yorktown. At about the same time, a French naval fleet commanded by Rear Admiral François Joseph Paul, the Comte de Grasse, won a decisive battle against a British fleet led by Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Graves at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Paul and his ships kept the British fleet from reaching Cornwallis’ troops at Yorktown, which eventually forced Cornwallis to surrender to George Washington there, effectively ending the American Revolution in the colonists’ favor.

Can’t Buy Me Love

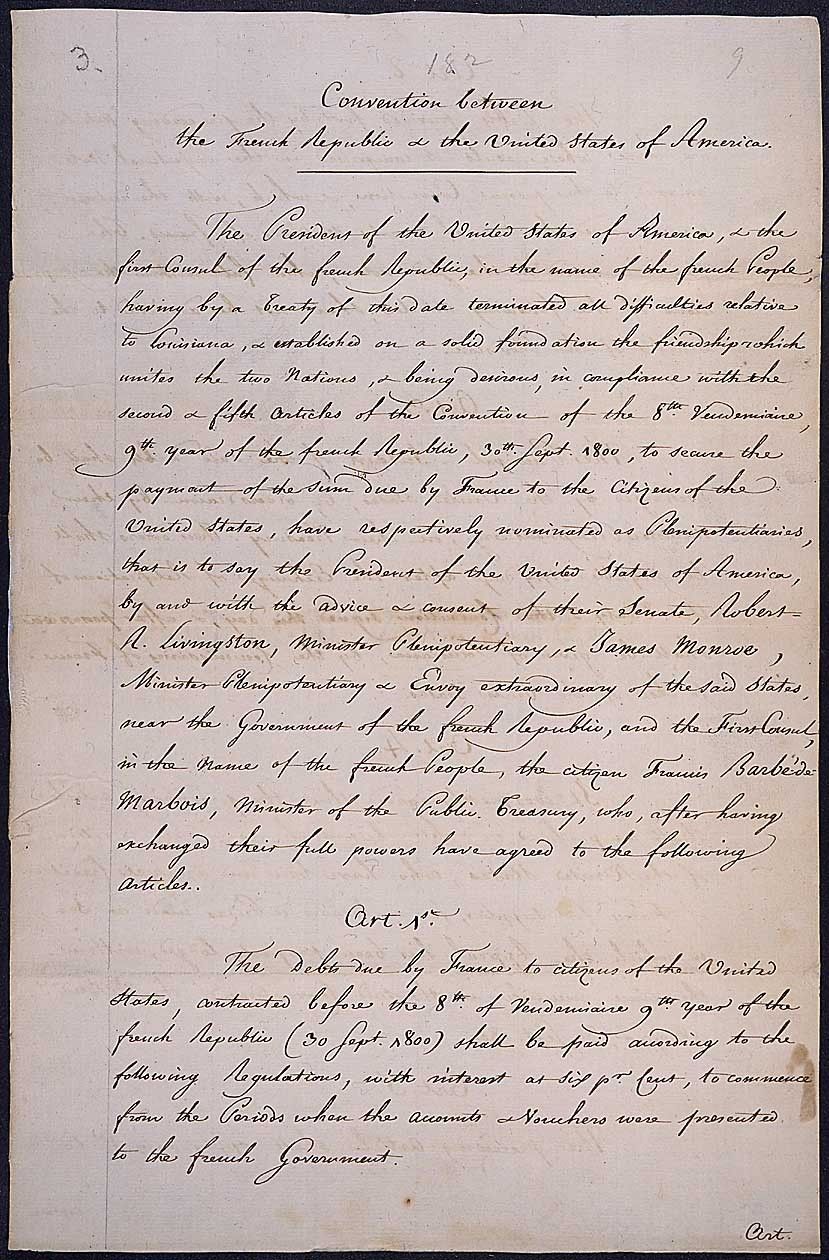

French copy of the Louisiana Purchase Treaty

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

Payment for Louisiana

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

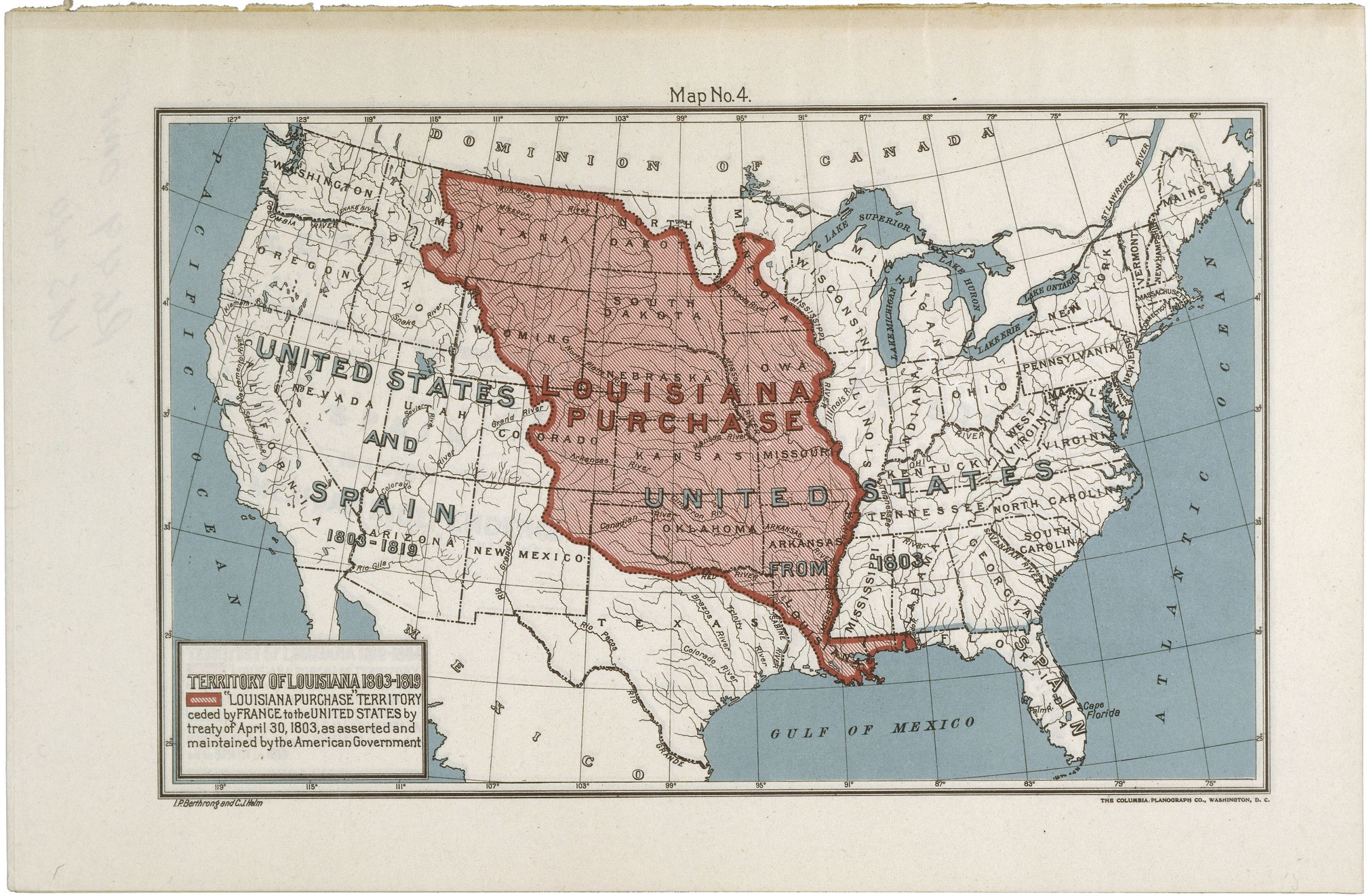

Nothing says love like offering your beloved a great investment opportunity, right? In 1803, Napoleon Bonaparte, who had been at war with Britain for years with no end in sight, and who also saw little monetary profit coming in from his vast empire in North America, made Thomas Jefferson an offer he couldn’t refuse: for the modest sum of $15 million dollars, the United States could become the proud possessor of the Louisiana Territory, 530,000,000 acres of land west of the Mississippi River that would effectively double the size of the nation, give the country unfettered access to the key ports of New Orleans and St. Louis and eventually encompass all or part of 15 states and portions of two Canadian provinces: Arkansas, Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas and Wyoming, and Alberta and Saskatchewan. The price amounted to about $18 per square mile—a bargain by anyone’s standard.

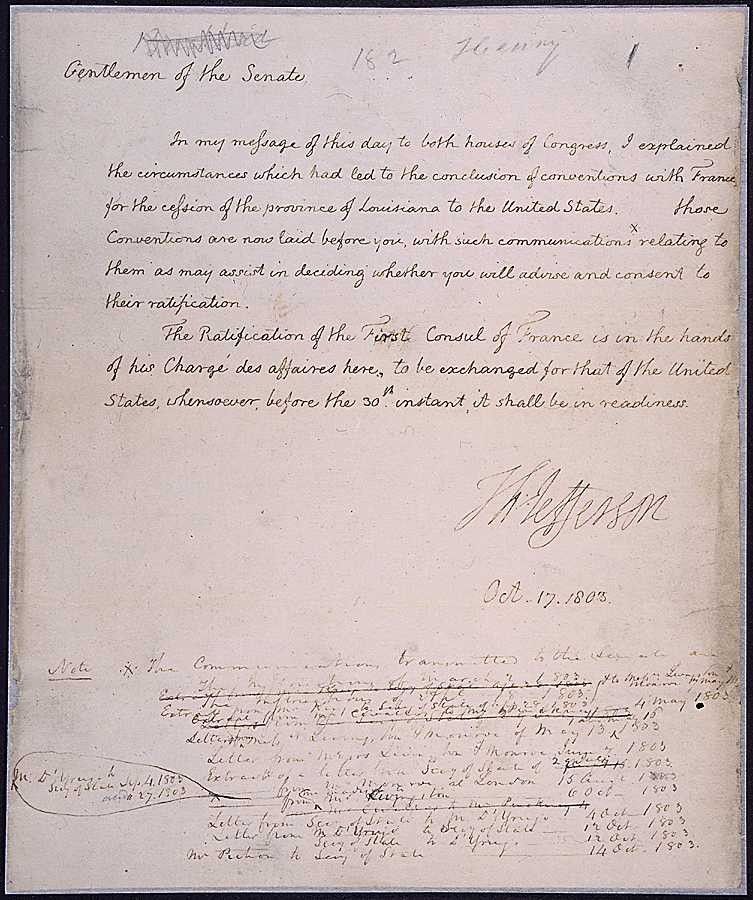

Jefferson’s message to the Senate seeking consent for the Louisiana Purchase

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

Map of Louisiana Purchase Territory

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

The ink was barely dry on the agreement when Jefferson—long a devoted Francophile, by the way—dispatched William Clark and Meriwether Lewis and the Corps of Discovery westward from Washington, D.C., on a journey of exploration that took them all the way to the West Coast. Along the way, they drew maps and recorded their encounters with the wildlife, the fauna and the Native Americans they encountered. The trip there and back to Washington, D.C., took two years.

Our Love Language Is Gifts, Actually

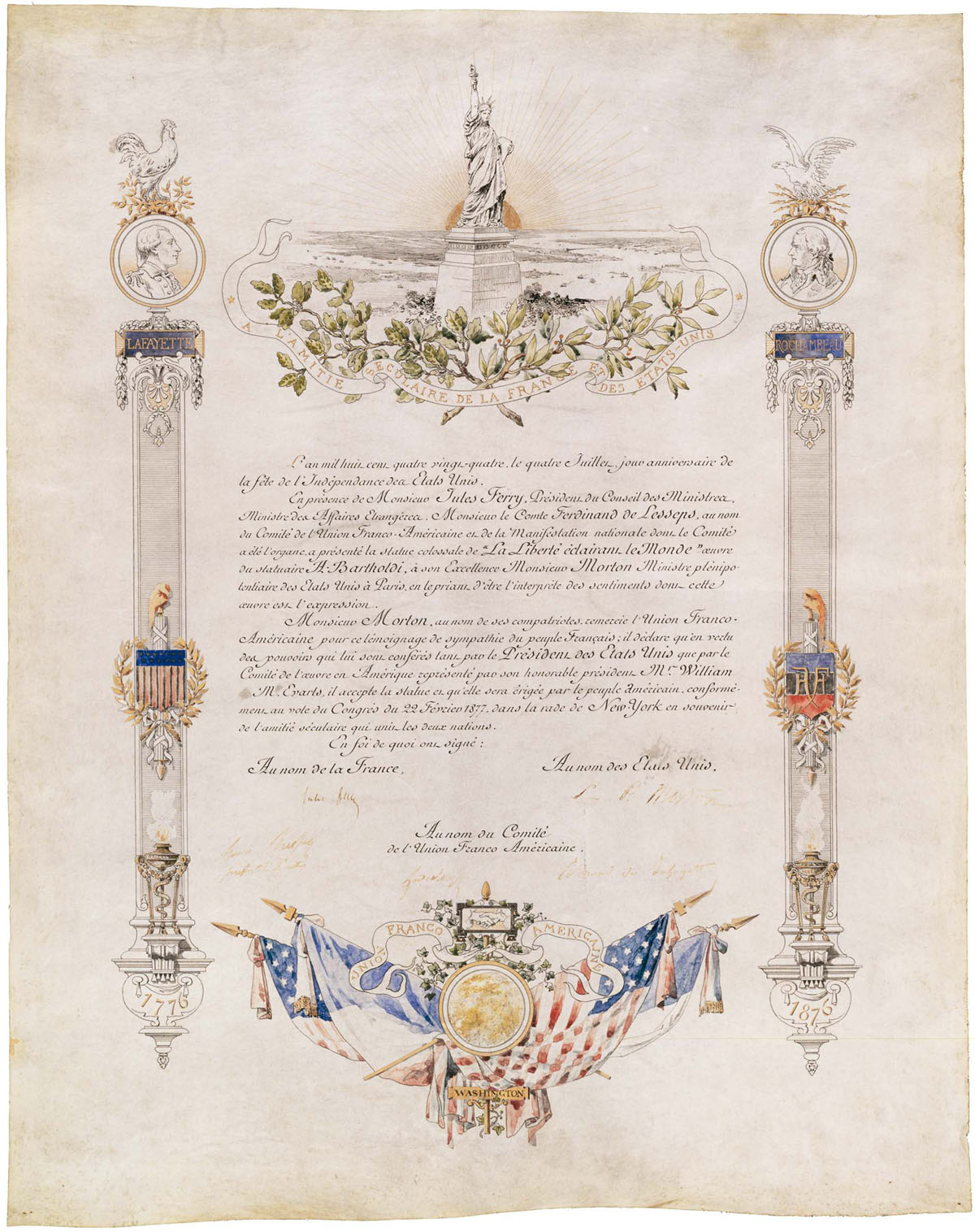

Deed of gift of the Statue of Liberty–July 15, 1884

And nothing also says love like the perfect gift. The Statue of Liberty, titled by her creator, the French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, La Liberté éclairant le monde (“Liberty Enlightening the World”), was given to the people of the United States by the people of France. Made of a copper skin riveted over an iron framework constructed by Gustave Eiffel, the builder of the famous tower in Paris, she stands on Liberty Island in New York Harbor in New York City, where since 1896 she has been an icon of freedom.

Statue of Liberty in Paris, France

National Archives Identifier: 19997487

Statue of Liberty in New York

National Archives Identifier: 68145985

Oui-Do

In the modern era, individual French politicians have continued to embody the friendship between France and the United States. Nicolas Sarkozy, who was president of France from May 2007 until May 2012, is such an admirer of the United States that he has been called “Sarko the American.” In response, he said he “loves his nickname.” During the 2008 U.S. presidential campaign, Sarkozy met with both John McCain and Barack Obama when they secured their parties’ respective nominations. He did not endorse either candidate, but he did call Obama his “buddy.”

And more recently, in February 2014, French President Francois Hollande paid Barack Obama the first state visit of the president’s second term. After meeting up in Washington, the two politicians went to Charlottesville, Virginia, and toured Thomas Jefferson’s estate at Monticello.

“I thought this was an appropriate way to start the state visit because what it signifies is the incredible history between the United States and France,” the president said after the tour had ended. “As one of our Founding Fathers, the person who drafted our Declaration of Independence, somebody who not only was an extraordinary political leader but also one of our great scientific and cultural leaders, Thomas Jefferson represents what’s best in America. But as we see as we travel through his home, what he also represents is the incredible bond and the incredible gifts that France gave to the United States, because he was a Francophile through and through.”

“We were allies in the time of Jefferson and Lafayette,” Hollande replied. “We are still allies today. We were friends at the time of Jefferson and Lafayette and will remain friends forever.”

View this profile on InstagramNational Archives Foundation (@archivesfdn) • Instagram photos and videos