Ceiling and Visibility Unlimited

Let’s not kid ourselves: just because two guys pulled it off the first time in 1903 doesn’t mean that the Wright brothers somehow kept women on the ground waving goodbye or just sitting in the window seat waiting for a cocktail. Women have had their fair share of sky blazers.

There is plenty of history to share when it comes to women in aviation. Just seven years after the flight at Kitty Hawk, the first woman piloted a flight in the U.S. Apparently she was “only allowed” to taxi the planes – oops. Let’s keep in mind this is still a solid 10 years before women were trusted with the right to vote! Over the years (and notably during World War II), acceptance and necessity grew the ranks of women pilots as well as related roles such as mechanics, factory workers, and flight controllers. Of course, today, as you read this, a woman flight engineer is circling the globe on the International Space Station.

Whether you are a fan of the television show “Flying Wild Alaska” or one of the many other programs that document the accomplishments of women in the air, this newsletter is for you. Buckle up.

✈

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

A Pioneer in Flight

The Maker of Pilots: Aviator and Civil Rights Activist Willa Beatrice Brown

in Rediscovering Black History – Say It Loud Blog

Born in Kentucky in 1906, Willa Beatrice Brown was a pioneer in the fledgling aviation industry when Black people were actively discouraged from learning to fly. She became the first African American woman to get a pilot’s license in the U.S., the first African American woman to hold both a pilot’s license and an aircraft mechanic’s license and the first African American officer in the Civil Air Patrol. In addition to being a pioneer in flight, she was also one in politics, as the first African American woman to run for Congress. As co-owner of the Coffey School of Aeronautics in Chicago with her then-husband, Cornelius Coffey, she trained hundreds of Black pilots, including several who later became Tuskegee Airmen.

The Lift-off of Combat Restrictions

Female Fighter Pilots and

the Combat Exclusion Policy

in the Unwritten Record Blog

On July 26, 1963, President John F. Kennedy hosted an event in the White House Rose Garden in honor of the issuance of a postage stamp depicting Amelia Earhart. Among the attendees were several members of the 99 Club of Women Pilots. Kennedy commented that he thought the time had come for women to get out of the house and “into the air.”

Thirty years later, in 1993, the U.S. Armed Forces rescinded the Combat Exclusion Policy, which banned women from serving in combat. The change only applied to pilots—all restrictions on women participating in combat weren’t lifted until 2013.

Women pilots quickly stepped up to take their place in combat. Jeannie Leavitt became the first woman combat pilot in the U.S. Air Force in 1993. She rose to the rank of major general and also became the first woman to command an Air Force combat fighter wing in 2012.

Other women soon joined the ranks of Air Force fighter pilots. In 1993, Sharon Preszler became the first female active-duty fighter pilot, serving in Iraq. In 1995, Martha McSally flew in combat in Kuwait in 1995. McSally also served as the first female commander of a combat aviation squadron that included fighters and bombers and later, as a United States Senator from Arizona.

Saving the Skies

Women at Work in the 1950s

in the Text Message Blog

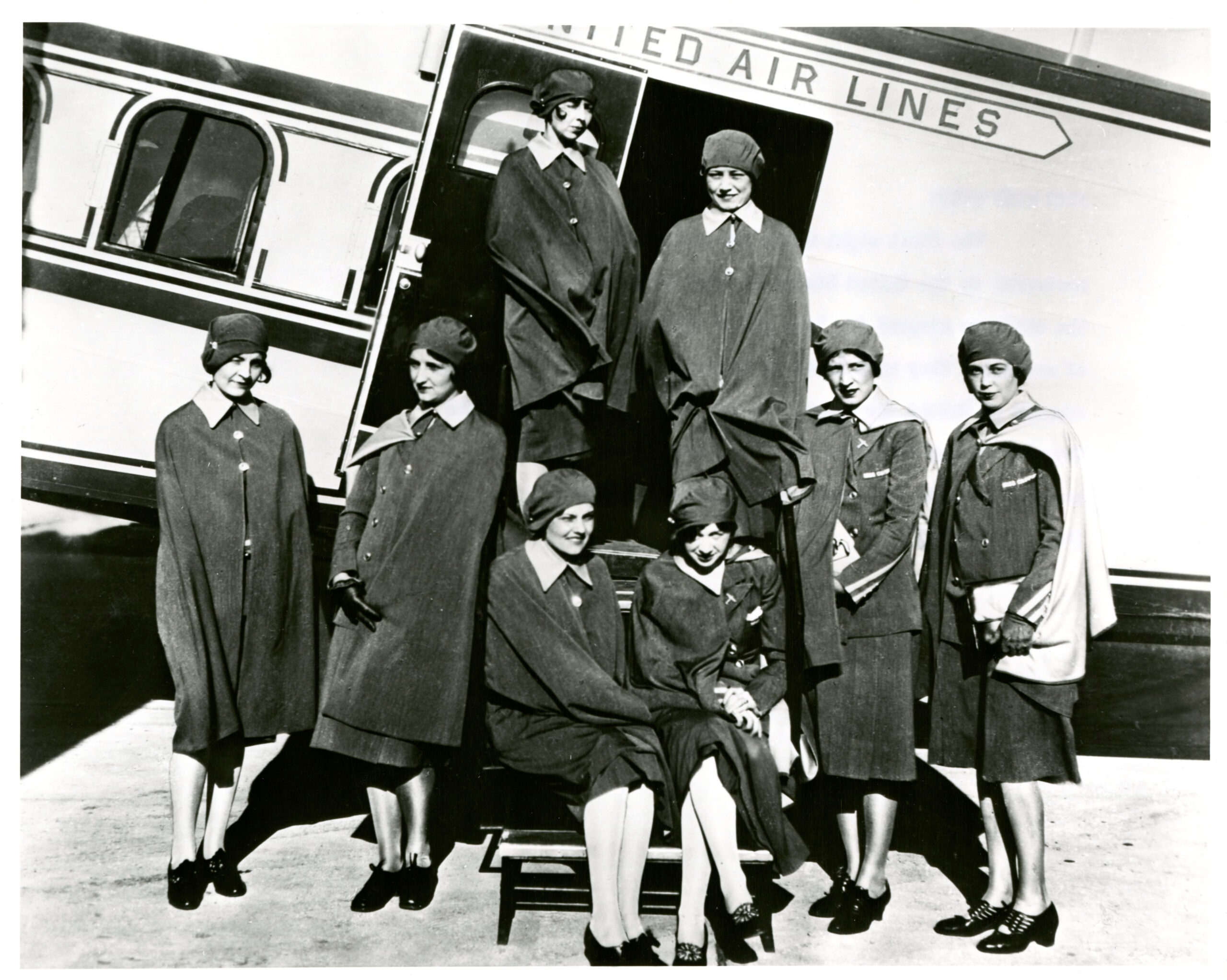

The early 20th century saw rapid change in the occupations that women could enter in the United States. Previously, women were largely limited to the professions of teacher, librarian, secretary and nurses. By the 1930s, however, women were working as stewardesses on commercial fights. Boeing Air Transport, then the owner of United Airlines, hired and trained the first eight women to work as stewardesses in 1930. The job gave women the opportunity to earn a living while traveling to locations both stateside and international.

1929 Women’s Air Derby’

Amelia Earhart preparing

for her last takeoff

Amelia Earhart is probably the most famous female pilot of the first half of the 20th century, but she was only one of a multitude of talented women who were flying then. In August 1929, Earhart competed with 19 other women in the 1929 Women’s Air Derby, which humorist Will Rogers dubbed the “Powder Puff Derby.”

The 20 pilots took off from Santa Monica Airport in California, bound for Cleveland, Ohio, a 2,759-mile trip they had to complete in nine days. Their route took them through California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri and Indiana before they reached Ohio and involved multiple stops over the nine-day journey. Each pilot was timed on each leg of the race, and the overall time determined the winner. Prize money totaling $8,000 was up for grabs, both for the best time for each of the legs of the trip and for the overall best time.

The aircraft the pilots flew were categorized as lighter airplanes or heavier, working aircraft. Of the 20 pilots who started the race, 14 finished within the time restraints: Edith Foltz, Chubbie Keith-Miller, Phoebe Omlie and Thea Rasche in the light aircraft division, and Amelia Earhart, Ruth Elder, Mary Haizlip, Opal Kunz, Blanche Noyes, Gladys O’Donnell, Neva Paris, Louis Thaden, Mary Von Mach and Vera Dawn Walker in the heavy aircraft division.

Records Relating

to Amelia Earhart

Having wrecked their aircraft and having to replace them before they could continue the race, four more pilots reached Cleveland after the allotted time was up: Pancho Barnes, Clair Fay, Ruth Nichols and Bobbi Trout. One pilot, Margaret Perry, had to drop out when she caught typhoid fever, and Marvel Crosson died of injuries she sustained when her plane crashed.

The air derby generated tremendous publicity all across the country. All along the way, the pilots dealt with mechanical problems, bad weather and unruly spectators. They were expected to fly all day and then attend formal dinners each night. No matter what Will Rogers called them, these women were anything but fragile.

In the end, Louis Thaden won the heavy aircraft division and Phoebe Omlie won the light division. Earhart placed third. Thaden dedicated her victory to Marvel Crosson.

The Last Place You Look

Wright patent located

Do you sometimes misplace your shoes, keys, phone or backpack? Don’t feel too bad—even professionals sometimes put something important in a place that’s so “safe” that they can’t find it later.

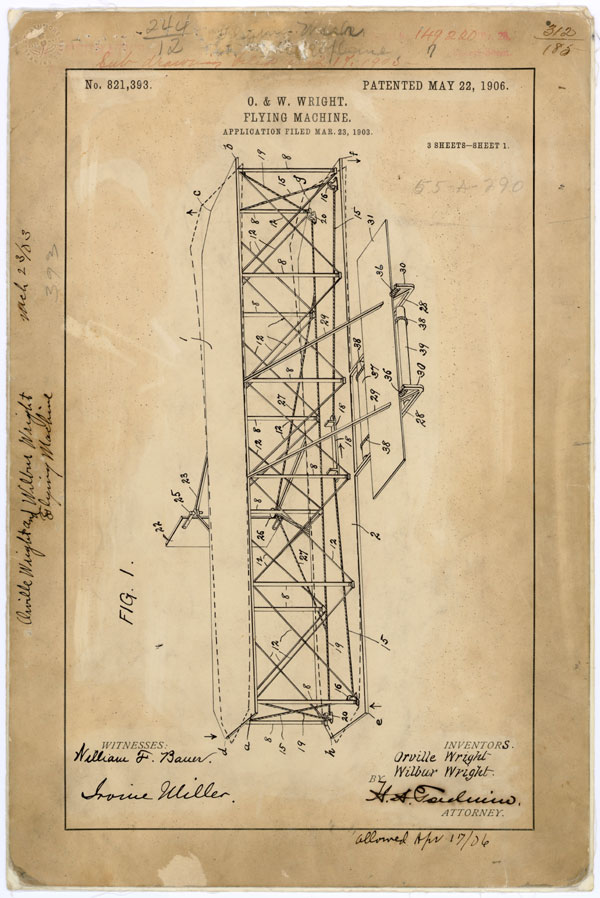

In 1979, the National Archives loaned portions of the file for the patent that was awarded to Wilbur and Orville Wright for their Wright flyer in 1906 to an exhibition commemorating the 75th anniversary of the flyer’s first flight at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. When the documents were returned to the Archives, the patent file was misfiled among other patent records.

The file was found in 2016, 10 years after the Archives created an Archival Recovery Team specifically charged with locating misplaced files. The National Archives is the repository of more than 107,600 cubic feet of patent files, so it’s not hard to imagine how easy it might be to put something in the wrong box—and how difficult it would be to find it again. In addition to the patent for the Wright flyer, the Recovery Team found nine Presidential pardons and a George E. Pickett letter dated 1857, written before he went on to be a general in the Confederate Army during the Civil War.