Batting Away Jim Crow

The Civil Rights Movement had many arenas: buses, schools and lunch counters. Beyond the well-publicized events in business, government and education, the conflict played out on the field throughout much of sports history.

The desegregation of sports was a bumpy ride that demonstrates the complexity of race relations throughout the 20th century. Black athletes were welcomed in some sports, but not others; were embraced for their success during a game, but shunned the rest of the time.

Visitors to the Archives’ exhibit “All American: The Power of Sports” can explore the history of athletes as activists and the challenges they faced on and off the field.

In this issue

The first moments of desegregation in any professional sport in the United States are always fraught…

The great boxer Joe Louis became the first Black athlete who was widely embraced by white Americans…

Despite his Olympic achievements, Owens returned to an America that was still riven by Jim Crow racism…

History Snack

Kickoff to Desegregation

The first moments of desegregation in any professional sport in the United States are always fraught. Frederick Douglass “Fritz” Pollard, an African American student, played halfback at Brown University, where he was an All-American. Walter Camp, known as “the Father of American Football” in the early days of the sport, called Pollard “one of the greatest runners these eyes have ever seen.”

After serving in World War I, Pollard turned pro in 1919 and played for the Akron, Ohio Pros, thereby becoming the first Black player in the American Football League, later christened the National Football League. The Pros were undefeated that season. Along with Bobby Marshall, Pollard was one of only two Black players in the league in 1920. In 1921, the Pros hired Pollard as co-coach of the team, making him the first African-American head coach in the league. He also continued to play while he coached.

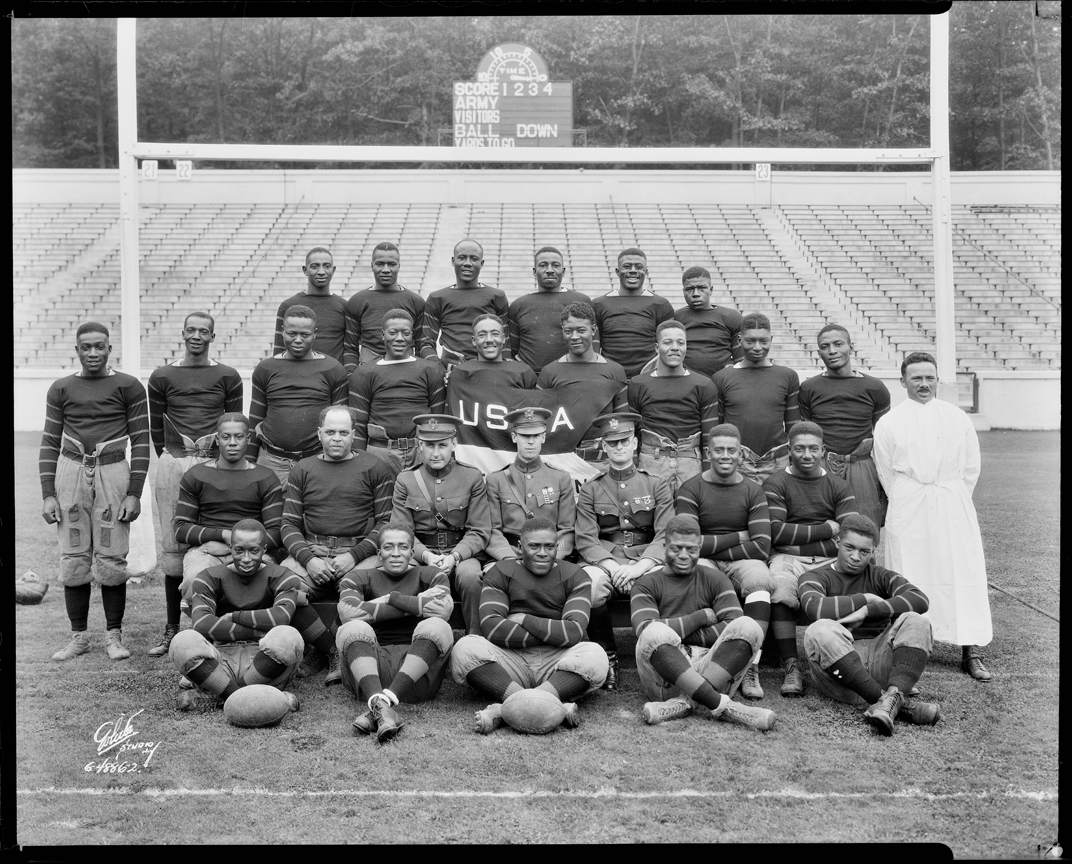

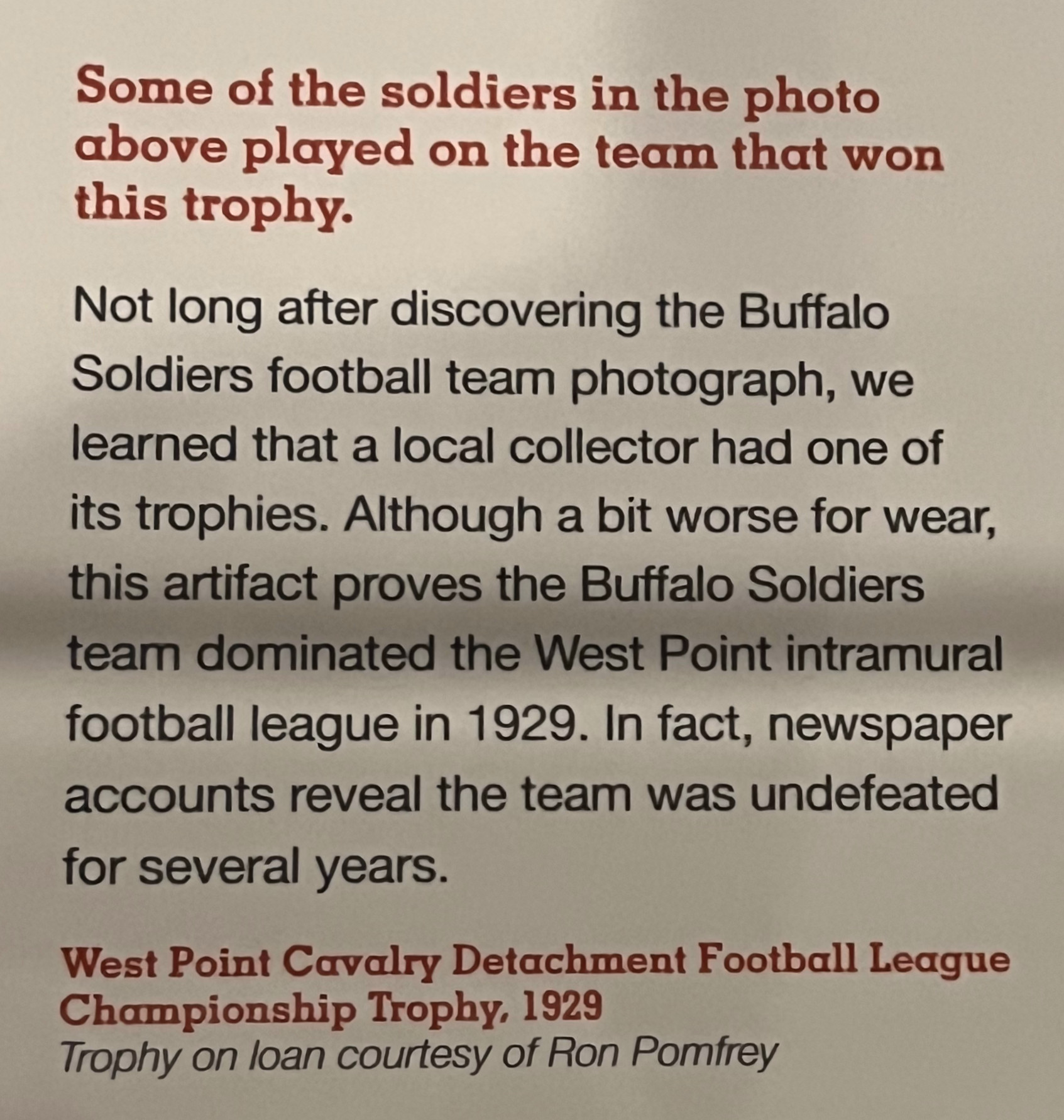

Black players continued to play important roles in the development of football throughout the 1920s. At West Point, a unit of Buffalo Soldiers was instrumental in instructing the academy’s football team both tackling and defensive techniques. That unit spent one season undefeated, and their 1929 championship trophy is currently on display in “All American.”

Predictably, Pollard endured blatant racism throughout his career. Frequently as he took the field as a college player, fans of the opposing team sang “Bye, Bye, Blackbird!” Furthermore, his ground-breaking entrée into the NFL didn’t really pave the way for other Black players. In a speech given at Pollard’s induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2005, his grandson, Steven Towns, talked about the era that immediately followed Pollard’s retirement from playing football.

When injuries took their toll on Fritz’s body, he was forced to end his career, but he wasn’t out of football. Sometime in 1934, in what was considered one of the darkest eras in sports, a so-called ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ was reached between the powerful owners of the NFL to begin the process of eliminating black players from pro football. And no African American played again until 1946. . . My grandfather fought this policy and never stopped fighting for re-integration of the league.

It was George Preston Marshall, who owned the Washington Redskins, who enforced the “unspoken rule” that kept Black players out of the game until after World War II.

Nixon meeting with the Redskins (now know as the Washington Commanders), 1971

National Archives Identifier: 194738

That didn’t change until the Cleveland Rams moved to Los Angeles and wanted to play ball in the LA Memorial Coliseum, which was funded with tax dollars and consequently was beholden to the local, notably diverse population. A Black sportswriter, William Harding, challenged the Rams management by asking them if Black players would be signed to play on the team. The Rams general manager Charles Walsh decided it would be expedient to recruit some Black players, so he signed Kenny Washington and Woody Strode. Soon after, the Cleveland Browns signed Marion Motley and Bill Willis. Those signings broke the color line once and for all in the National Football League.

Incidentally, the Washington Redskins, now the Commanders, were the last NFL team to desegregate.

Knocking Out White Supremacy

Boxing is a perplexing example of a sport in which Black athletes were exalted relatively early on as champions and were pilloried in almost the same moment for their private lives. Jack Arthur Johnson, known as “Jack Johnson,” became the first Black world heavyweight boxing champion in 1908, a title he held until 1915, at the very height of the Jim Crow era in the United States. In 1910, Johnson fought James J. Jefferies, a former heavyweight champion who came out of retirement to face Jackson in what was billed as “the fight of the century” and what had been, not so subtly, advertised as a combat to prove the superiority of white fighters over Black ones. Johnson defeated Jefferies after 15 rounds, effectively ending that debate.

Autobiographical manuscript by Jack Johnson

National Archives Identifier: 24680936

Johnson was an icon of athletic excellence for many Americans of all ethnicities, but he quickly ran afoul of the sensibilities of many people because of his relationships with white women. He was arrested on October 18, 1912, for violating the Mann Act, which forbids transporting a woman across state lines for “immoral purposes,” with Lucille Cameron, whom he later married. Cameron refused to testify against him, and the case was dismissed. He was charged with violating the act again less than a month later with Belle Schreiber, with whom he had been involved in 1909 and 1910, even though the Mann Act had not become law until after the alleged events took place. He was tried and convicted in June 1913 by an all-white jury and was sentenced to a year and a day in prison. He skipped bail and left the country, meeting up with Cameron in Montreal and then fleeing to France. They lived in Europe for seven years, where he fought matches to support them. They finally returned to the U.S. on July 20, 1920, where Johnson surrendered and served his sentence at the United States Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas, where he hand-wrote his autobiography. He was released on July 9, 1921.

President Trump pardons Jackson

Image courtesy of the New York Times

Once freed, Jack Johnson continued fighting for several more years and ran a number of other businesses. He died in a car accident in 1946. President Donald Trump formally pardoned him in 2018.

The great boxer Joe Louis became the first Black athlete who was widely embraced by white Americans. Louis’ managers, a Detroit-based bookmaker named John Roxborough and a boxing promoter from Chicago named Julian Craft, took charge of Louis’s boxing career and managed him carefully, making sure that he trained well, ate well and avoided many of the public mistakes that Jack Johnson had made. As a consequence, white boxing fans largely approved of Louis’ ascension to the heavyweight championship.

In 1936, as an aspiring champion, Louis fought the German boxer Max Schmeling, who defeated him for the first time in Louis’ professional career. The Nazi government made great hay out of Schmeling’s victory, touting it as proof of the superiority of the Aryan race. However, Louis defeated James J. Braddock on June 22, 1937, to become the heavyweight champion of the world. He was not satisfied with the title, however, saying, “I don’t want to be called champ until I whip Max Schmeling.”

Exactly one year later, on June 22, 1938, after public posturing and political propaganda from both sides, Joe Louis defeated Max Schmeling in a historic rematch in New York City that lasted two minutes and four seconds. It was the first time that many white Americans openly cheered for a Black athlete. The small towel on display in “All American” is embroidered with the events of that fight. It is quite literally the the towel that Max Schmeling “threw in” after his loss to Louis.

Joe Louis went on to hold the world heavyweight title until 1949. He won 25 consecutive title bouts, a record in all weight classes in boxing. He then went on to integrate the game of golf by appearing in a PGA event in 1952 under a sponsor’s exemption. Joe Louis died in 1981. By then, he and Max Schmeling had long since become good friends. Schmeling helped pay some of his funeral expenses and served as one of Louis’ pallbearers.

Performance, Not Power

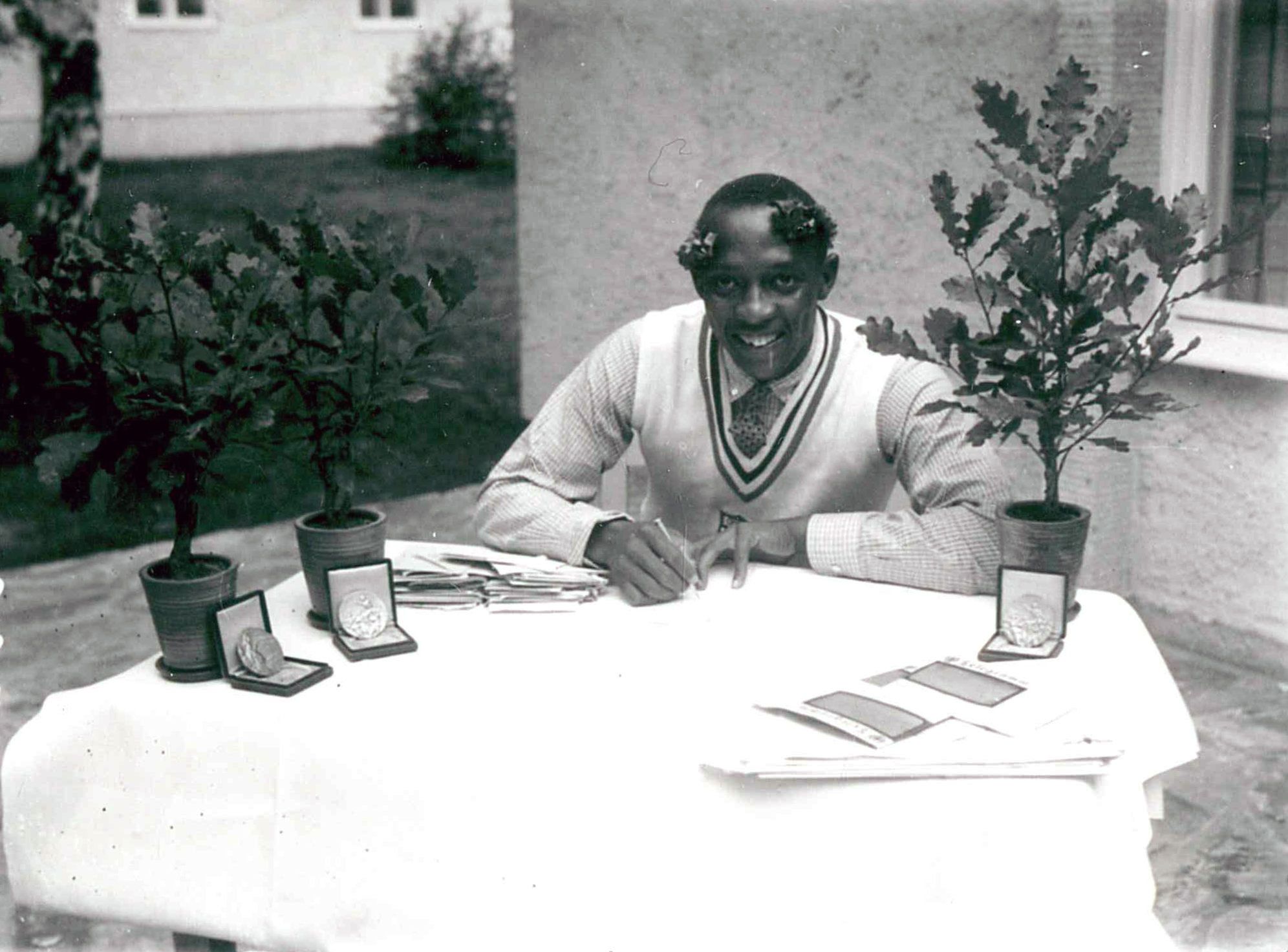

Jesse Owens 1936 telegram

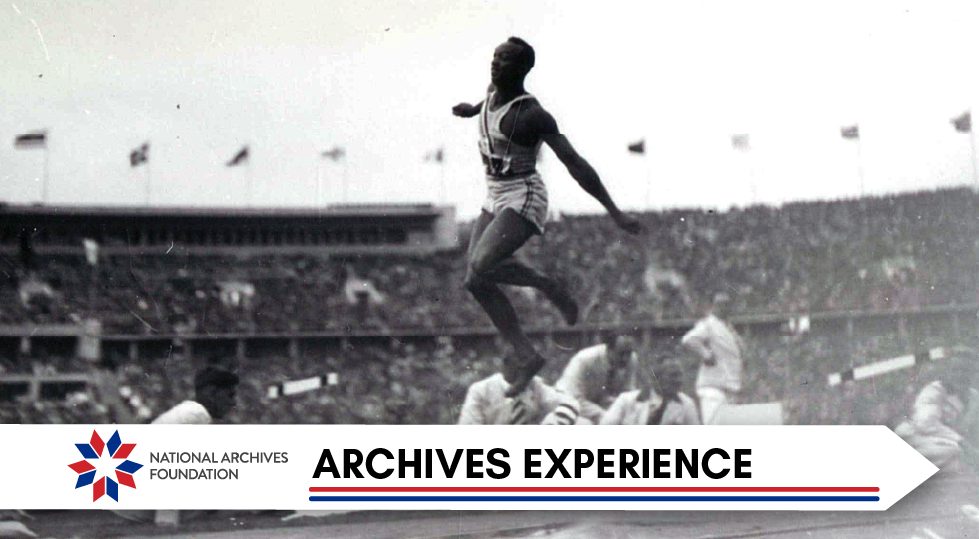

James Cleveland Owens, who went by “Jesse Owens,” was a Black American track and field athlete whose specialties were sprints and the long jump. He came to international attention when he won four gold medals at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, Germany, in the 100 meters, the 200 meters, the 4 by 100 meter relay and the long jump. Hitler had bragged endlessly that the 1936 Olympics would be a showcase of Aryan supremacy, a boast that crumbled in the face of Owens’ overwhelming domination of the track and field events. As the most successful athlete at the games, he was lauded with “single-handedly crushing Hitler’s myth of Aryan supremacy.”

Despite his Olympic achievements, Owens returned to an America that was still riven by Jim Crow racism. “I came back to my native country and couldn’t ride in the front of the bus,” he said. “I had to go to the back door. I couldn’t live where I wanted…I wasn’t invited to the White House to shake hands with the president either.” It was not until 1955, long after he had retired from competition, that President Dwight D. Eisenhower named Jesse Owens the “Ambassador of Sports” and asked him to represent the United States at the 1956 Olympics.

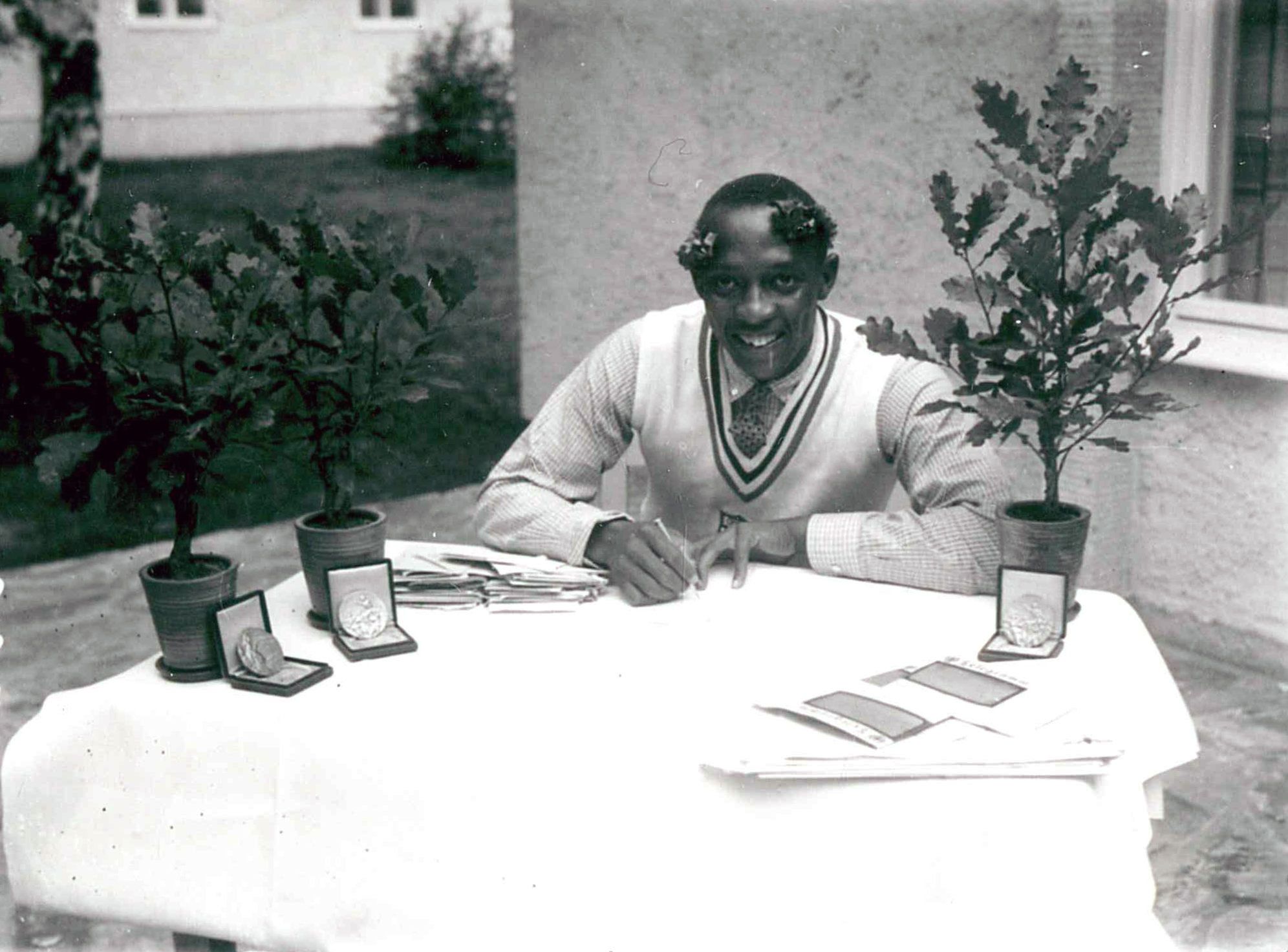

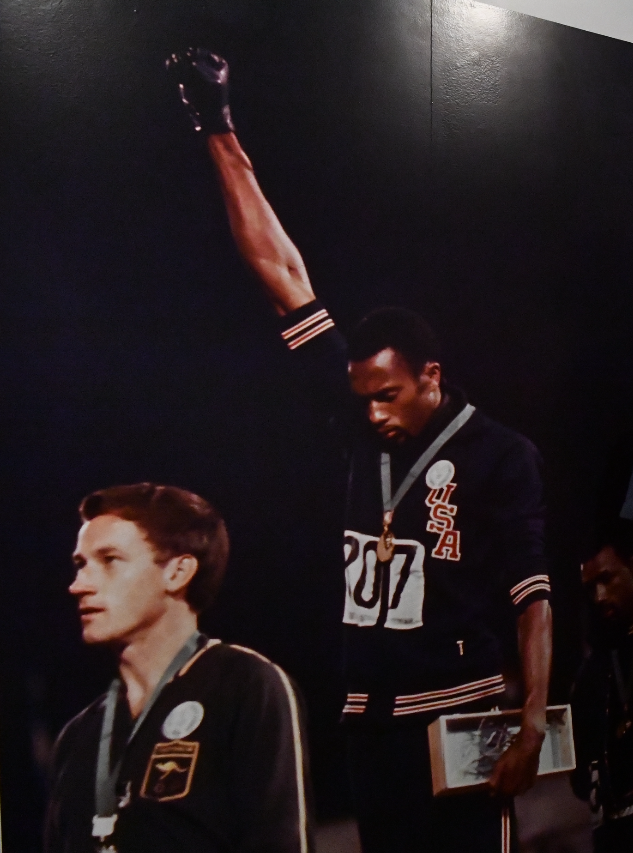

1968 Black Power Protest

US Embassy Mexico telegram to Secretary of State re: Black Power Protest

In 1968, the Black U.S. athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who had just won gold and bronze medals, respectively, in the 200-meter sprint at the Summer Olympics in Mexico City, raised their black-gloved fists in a “Black Power Salute” during the medal ceremony. Because making political statements on the medal podium was against the Olympic charter, the two were suspended from the team for their action and sent home.

Match Point

Althea Gibson Trophy

Trophy Detail

In a previous newsletter “An Equal Playing Field”, we covered Althea Gibson’s ascent to the tennis world and the groundbreaking progress Black women made in the wake of Title IX. Now on display in “All American” is Althea Gibson’s US Open Championship trophy from 1956. While Gibson made strides in women’s tennis, men’s tennis was dominated by Arthur Ashe.

Arthur Ashe was an American tennis player who personified the very best of the sport—athletic ability, shrewd, cerebral tactics, confidence and impeccable manners. Ashe was the first Black American man to win the U.S. Open, the Australian Open and Wimbledon and the first Black American to compete in the Davis Cup, which he helped the U.S. win for five competitions thereafter. He also helped found the Association of Tennis Professionals, and he cofounded the National Junior Tennis League. He played as a professional for 20 years, from 1959 until 1979, when he suffered a heart attack that forced him to retire. In that time, he secured 47 open era career titles, a singles record of 681-225 and a doubles record of 315-173.

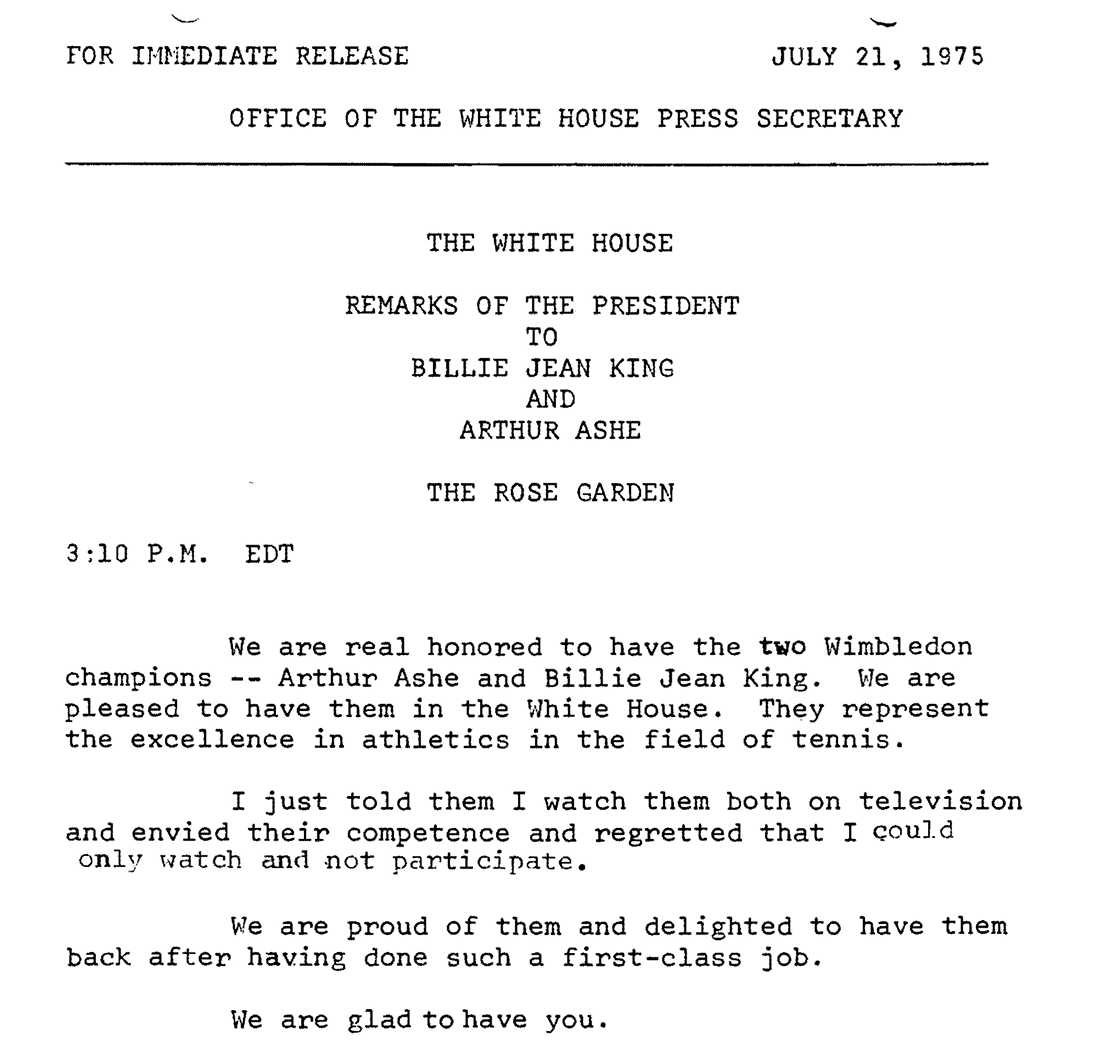

Ford Remarks to Billie Jean King and Arthur Ashe

National Archives Identifier: 7340152

But Ashe was as well respected for his demeanor on the court as his prowess. He was born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1943, and he learned to play tennis on the courts in the segregated public parks in that city. He attracted the attention of Dr. Robert Johnson, a legendary tennis mentor who lived in Lynchburg, Virginia, who also worked with Althea Gibson and who coached Ashe to the highest echelons of high-school tennis in the nation. Ashe won a full scholarship to the University of California, Los Angeles, and from there, his career was launched.

Reagan shakes hands with Ashe

National Archives Identifier: 75856909

After Ashe’s retirement, he devoted himself to combatting inequality for all minorities, including racial minorities and women. When he suffered a second heart attack in 1983, Ashe underwent bypass surgery, during which he contracted HIV from a blood transfusion. An extremely private man, he kept his illness secret until 1992, when he was forced to go public with the news on April 8, because a story about it was about to run in USA Today. He then established the Arthur Ashe Foundation for the Defeat of AIDS and dedicated himself to educating the public about HIV and AIDS. Shortly thereafter, Sports Illustrated named him Sportsman of the Year. He completed his autobiography, “Days of Grace,” only a few days before he died on February 6, 1993, of AIDS-related pneumonia. Among the many awards and accolades Arthur Ashe has received, ESPN presents the Arthur Ashe for Courage Award to a member of the sports community “who best exhibits courage in the face of adversity.”

View this profile on InstagramNational Archives Foundation (@archivesfdn) • Instagram photos and videos