Ballot Box Barriers

The midterm elections are just around the corner, and millions of Americans will proudly sport their “I Voted” stickers after taking part in the democratic process. Although the tradition of voting goes back to our nation’s founding, today’s voters better represent the tapestry of our nation. This is due to the activists who fought for suffrage.

Susan B. Anthony, Ida B. Wells and Martin Luther King, Jr., are just a few of the well-known leaders for voting equity. But less familiar are the obstacles they faced in voting, unwritten but entrenched local restrictions and the laws that kept true representation out of the ballot box.

No matter who you cast your vote for, we encourage you to participate! Add your voice to promote the democratic process, and honor those who fought for decades to overcome political and legal barriers for the right to vote.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

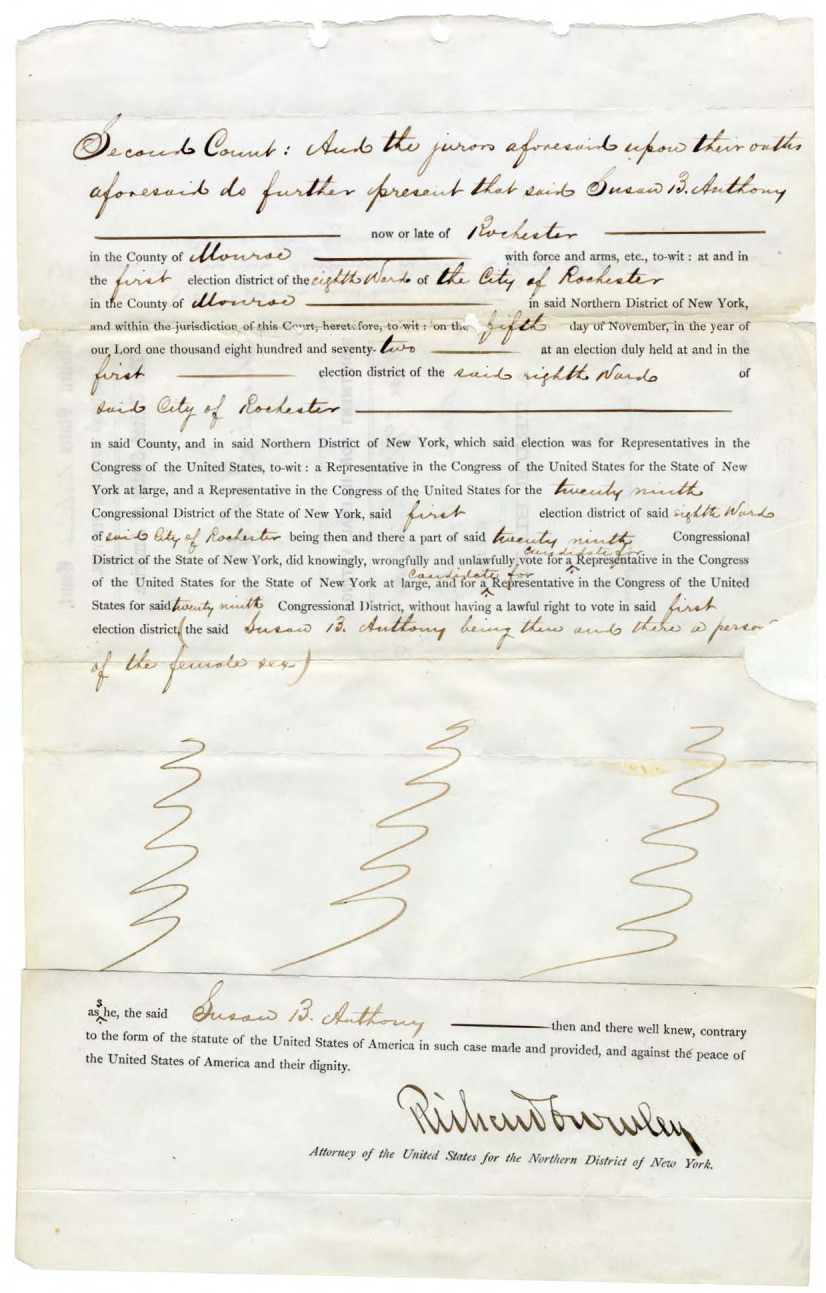

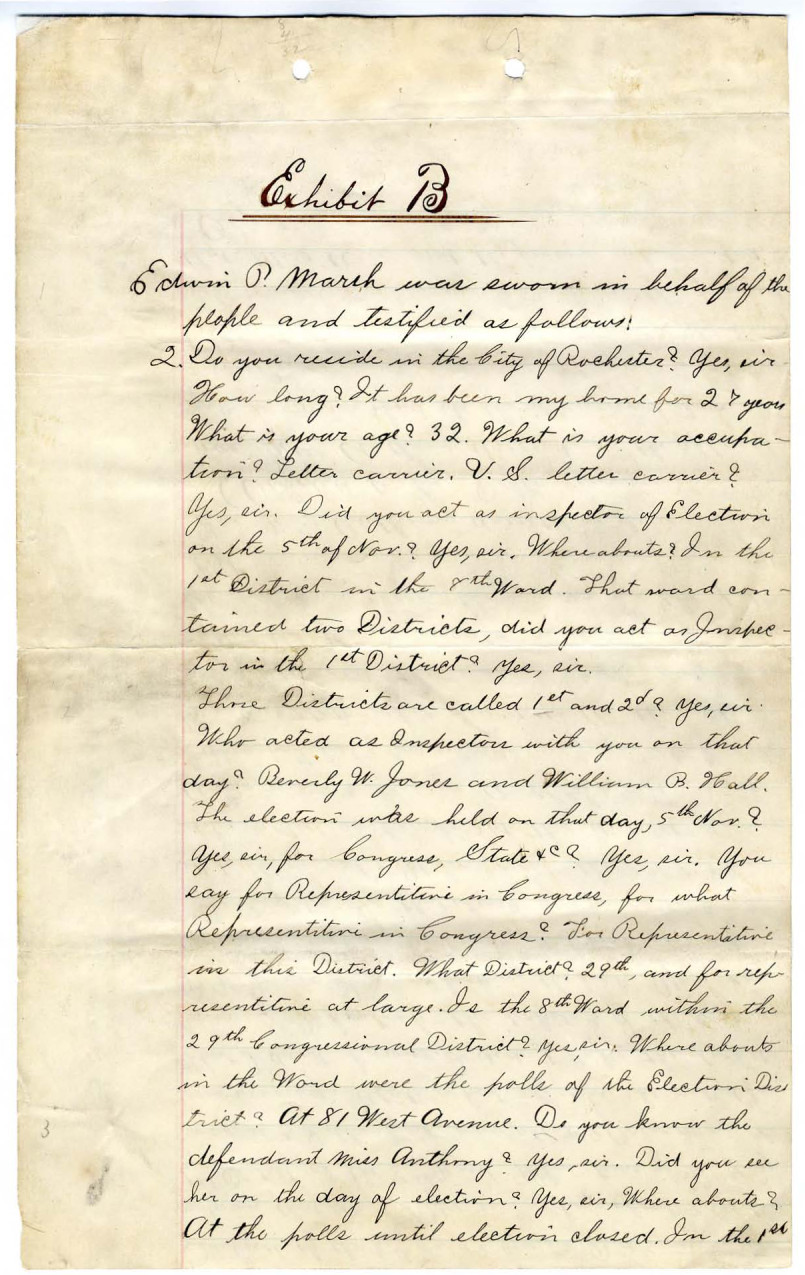

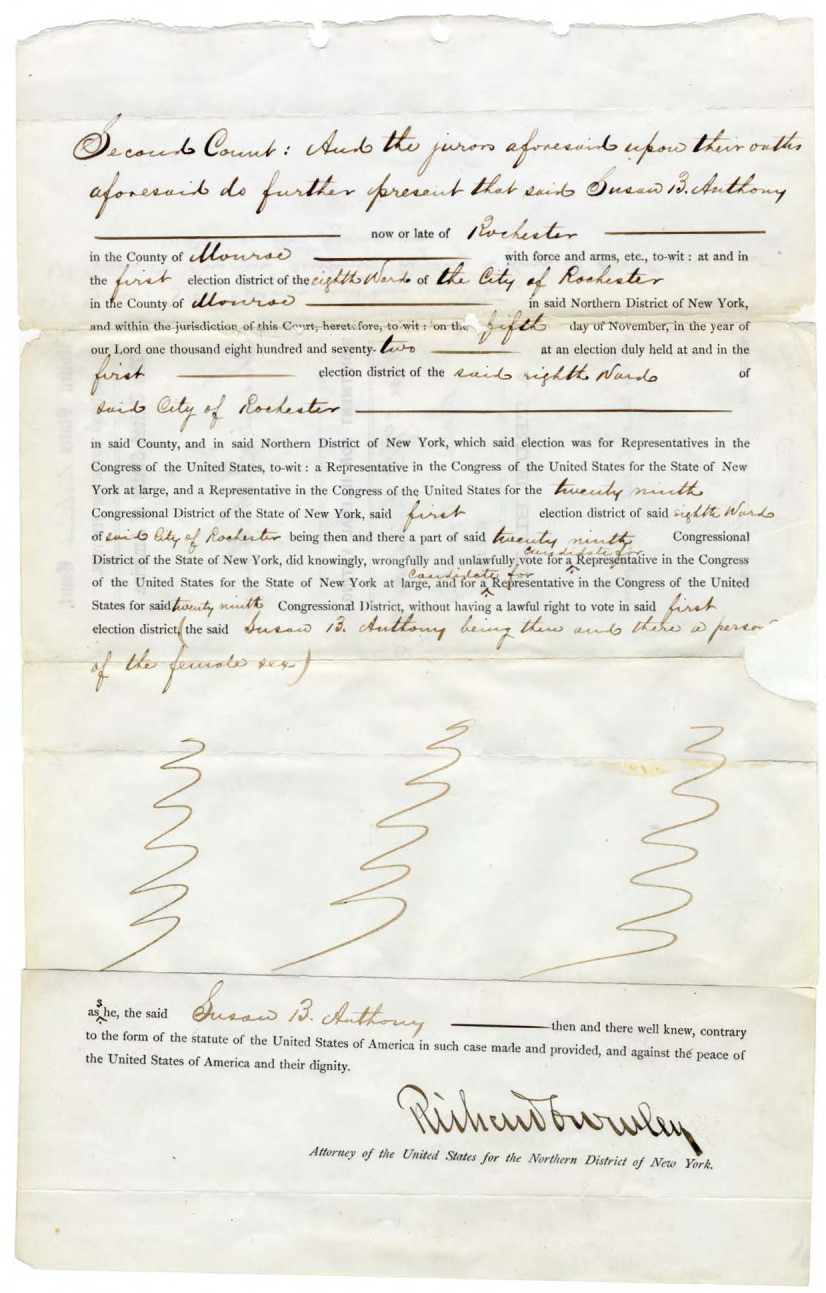

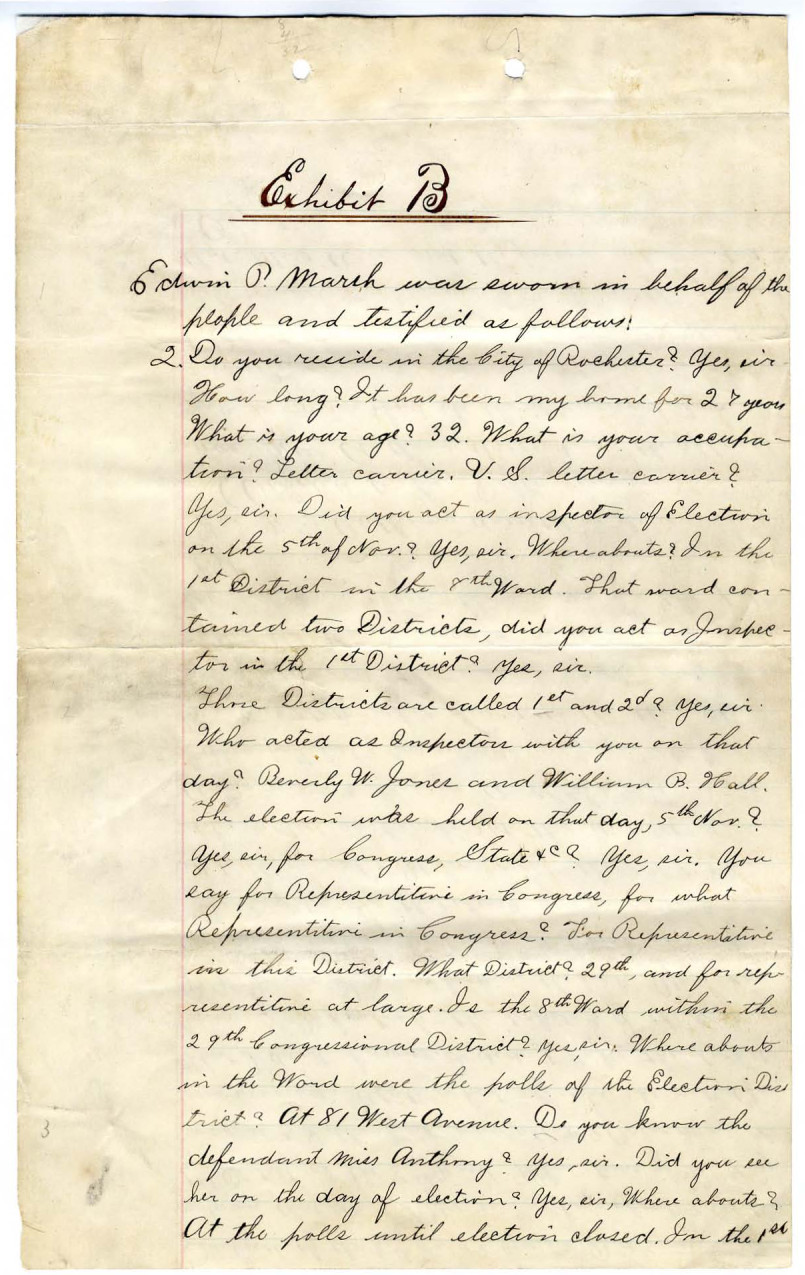

Unjust Penalty

Susan B. Anthony, that stalwart proponent of women’s suffrage, voted in the presidential election of 1872 on November 5 of that year, along with 14 other women from her ward in Rochester, New York, even though women did not yet have the right to vote in the United States. She and other members of the National Women Suffrage Association had been emboldened to take this action by the language of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which reads in part, “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.”

A U.S. Deputy Marshal arrested Anthony on November 18, and she was charged with voting illegally. The other women were also arrested, but they were all released pending Anthony’s trial.

The trial, United States v. Susan B. Anthony, began on June 17, 1873, in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of New York. Quite contrary to the laws of the land, Ward Hunt, the judge, ordered the jurors to find Anthony guilty, and he didn’t allow her to speak in her own defense. After the jurors rendered their verdict, he asked Anthony if she had anything to say. Big mistake!

“In the most famous speech in the history of the agitation for woman suffrage, she condemned a proceeding that had ‘trampled under foot every vital principle of our government,” wrote Ann D. Gordon, the editor of the papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony at Rutgers University in “The Trial of Susan B. Anthony.” Hunt kept telling Anthony to sit down and shut up—she most emphatically did not. He finally fined her $100, to which she hotly responded that she would “never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty.”

Hunt didn’t order Anthony to be jailed for not paying her fine, which kept her from filing a writ of habeas corpus and thus gaining a hearing before the Supreme Court. She never paid the fine, nor were the other 14 women ever prosecuted for illegally voting in the election.

Susan B. Anthony made hay of her trial and conviction for the rest of her life. That December, at a meeting of the Union League Club on the subject of women’s rights in New York City on the centennial of the Boston Tea Party, she declared in a speech, “I stand before you tonight a convicted criminal… convicted by a Supreme Court Judge… and sentenced to pay $100 fine and costs. For what? For asserting my right to representation in a government, based upon the one idea of the right of every person governed to participate in that government. This is the result at the close of 100 years of this government, that I, a native born American citizen, am found guilty of neither lunacy nor idiocy, but of a crime—simply because I exercised our right to vote.”

Susan B. Anthony remains controversial more than 100 years after her death in 1906. On August 18, 2020, President Donald Trump pardoned Anthony for voting illegally in the 1872 presidential election. Kathy Hochul, the lieutenant governor of New York, immediately objected. According to the New York Times, Hochul wrote on Twitter, “As the highest ranking woman elected official in New York and on behalf of Susan B. Anthony’s legacy we demand Trump rescind his pardon. She was proud of her arrest to draw attention to the cause for women’s rights, and never paid her fine. Let her Rest In Peace, @realdonaldtrump.”

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

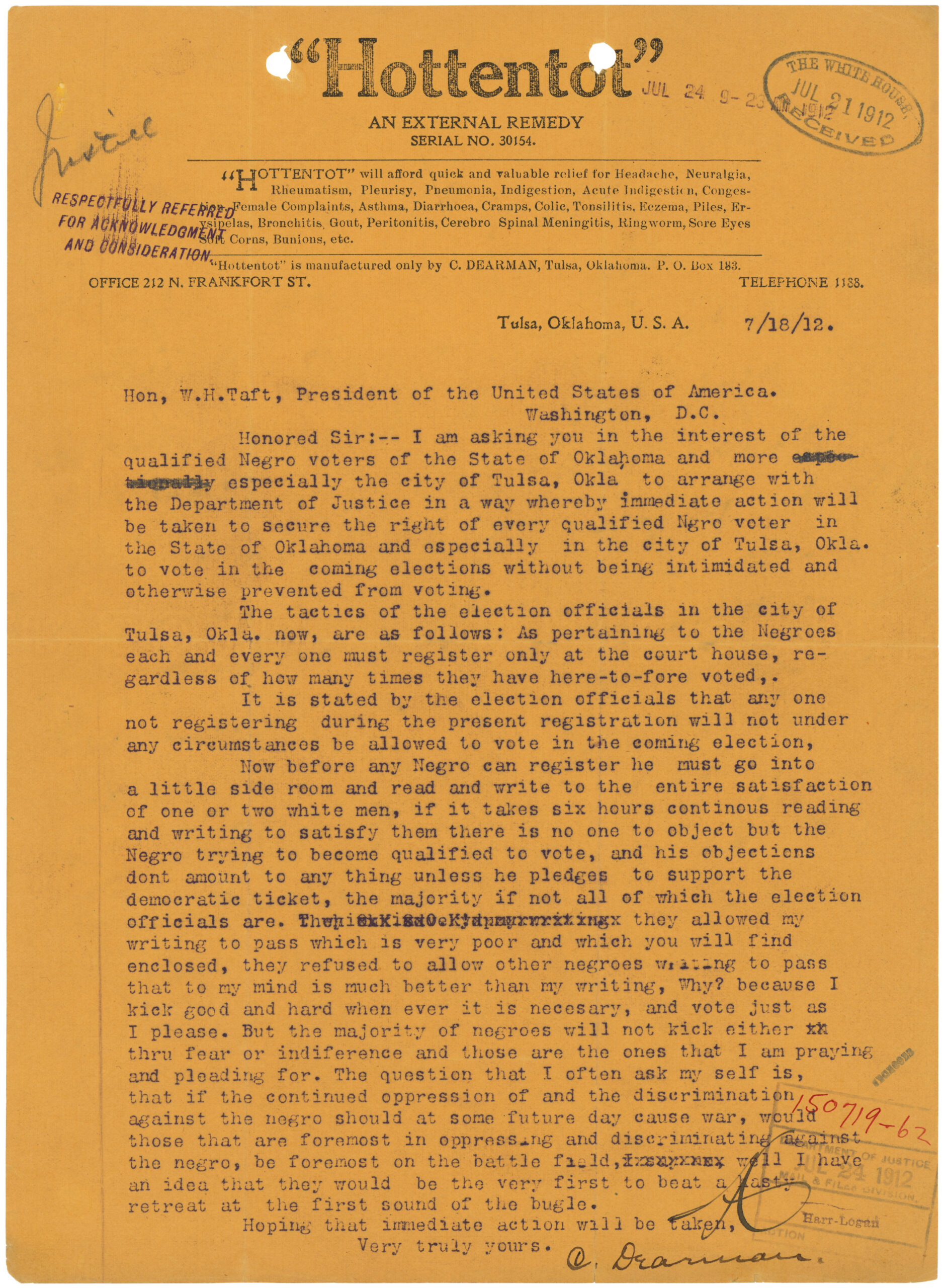

A Good, Hard Kick

When the Civil War began in 1861, four million people were enslaved in 15 southern and border states. As the war dragged to its close and the Union prepared to occupy the South, Abraham Lincoln, galvanized by his reelection in November 1864, pressured his allies in the House of Representatives to pass the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which would abolish slavery in the United States. The Senate had passed the amendment in April 1864, but it had stalled in the House of Representatives. On January 31, 1865, the House of Representatives finally passed the amendment by a vote of 119-56, just barely over the two-thirds majority needed to guarantee its passage. The amendment was ratified by the necessary number of states in December 1865, long after Lincoln had been assassinated.

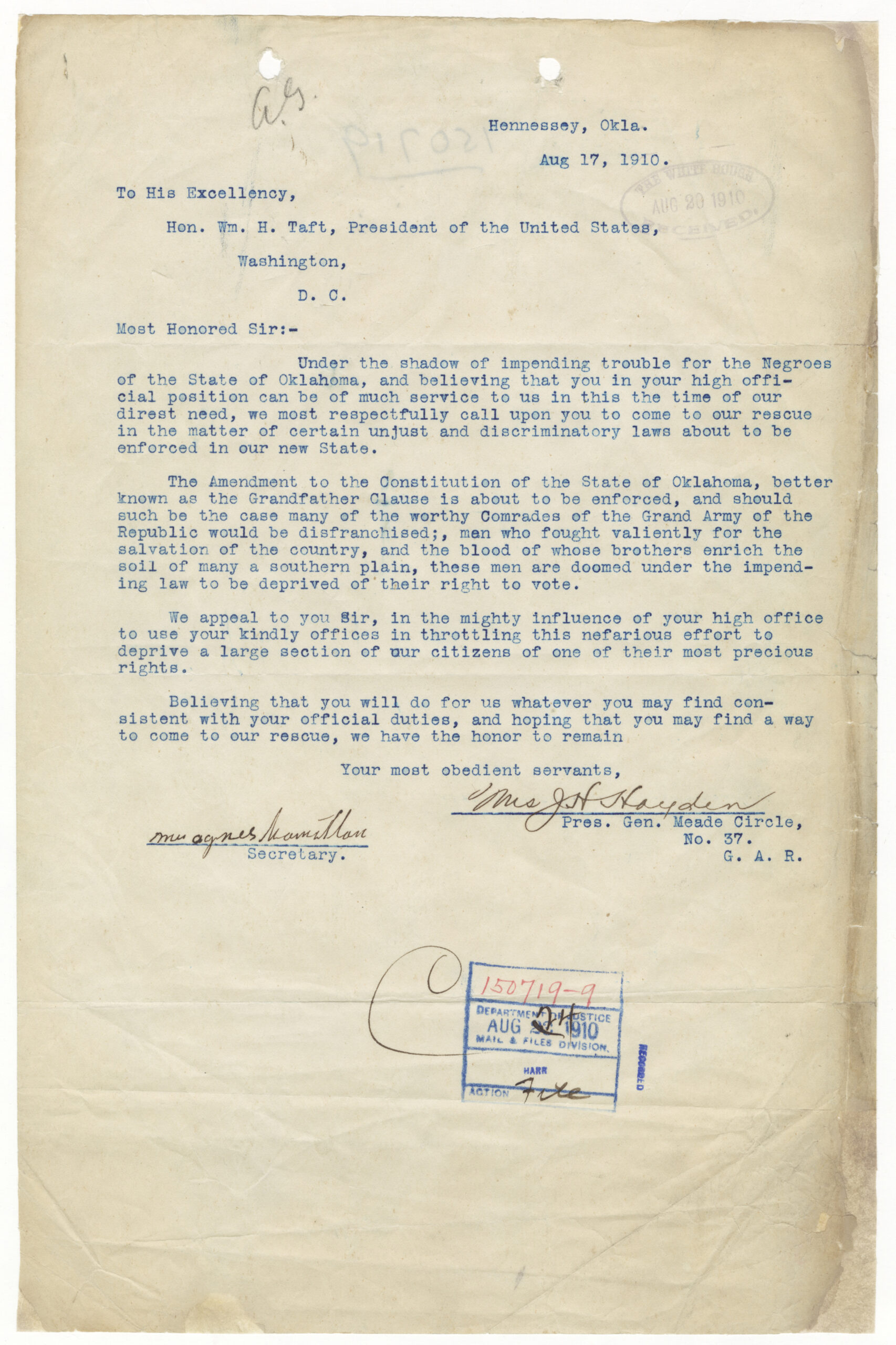

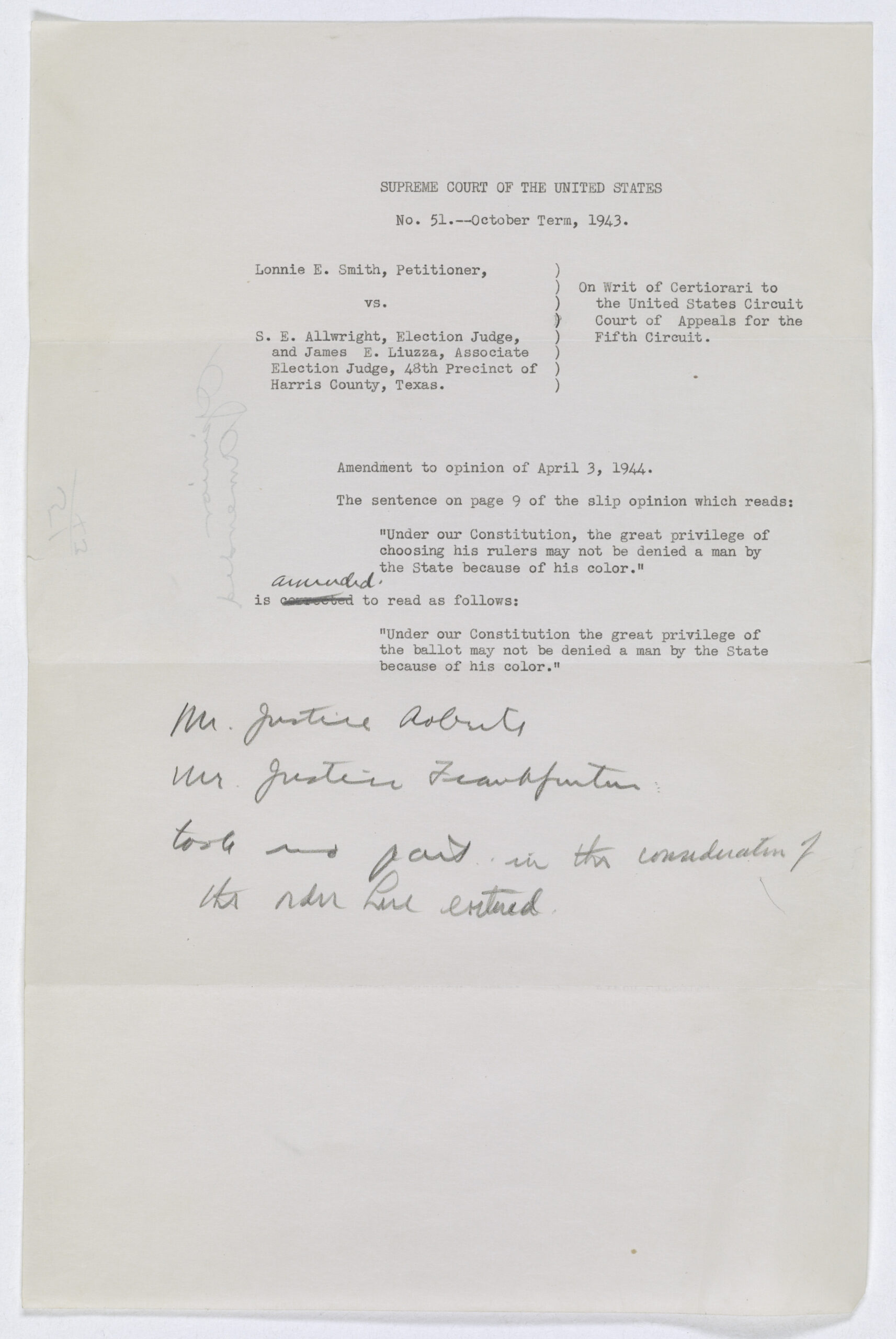

The 14th Amendment granted citizenship and all its privileges to Black Americans, and the 15th Amendment states, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” However, as soon as Reconstruction ended in the South in 1876 and white Southerners reclaimed power in state governments, they began to enact a slew of laws aimed at denying Black men their right to vote.

These actions included Jim Crow laws, which were local and state laws that primarily aimed at keeping the races segregated in the South. They took on broader issues than just the right to vote, including where Black people could live and work and how much they were paid, segregation of public facilities like movie theaters, parks and restaurants, waiting rooms in bus stations and airports, phone booths, water fountains, schools, jails, and hospitals, segregation of transportation like busses and trains and outlawing interracial marriage.

Immediately after the Civil War, the Ku Klux Klan was founded for the express purpose of terrorizing Black Americans and anyone who supported them. The Klan specialized in lynchings, rapes, tar-and-featherings and other violence aimed at intimidating Black people and specifically at keeping Black men from voting.

Southern legislatures also passed laws that required voters to pass literacy tests before exercising their constitutional right to the franchise. Literacy tests were administered unfairly and unevenly—Confederate veterans and property owners were often exempt, while Black men were given more stringent tests to ensure that they didn’t qualify to vote.

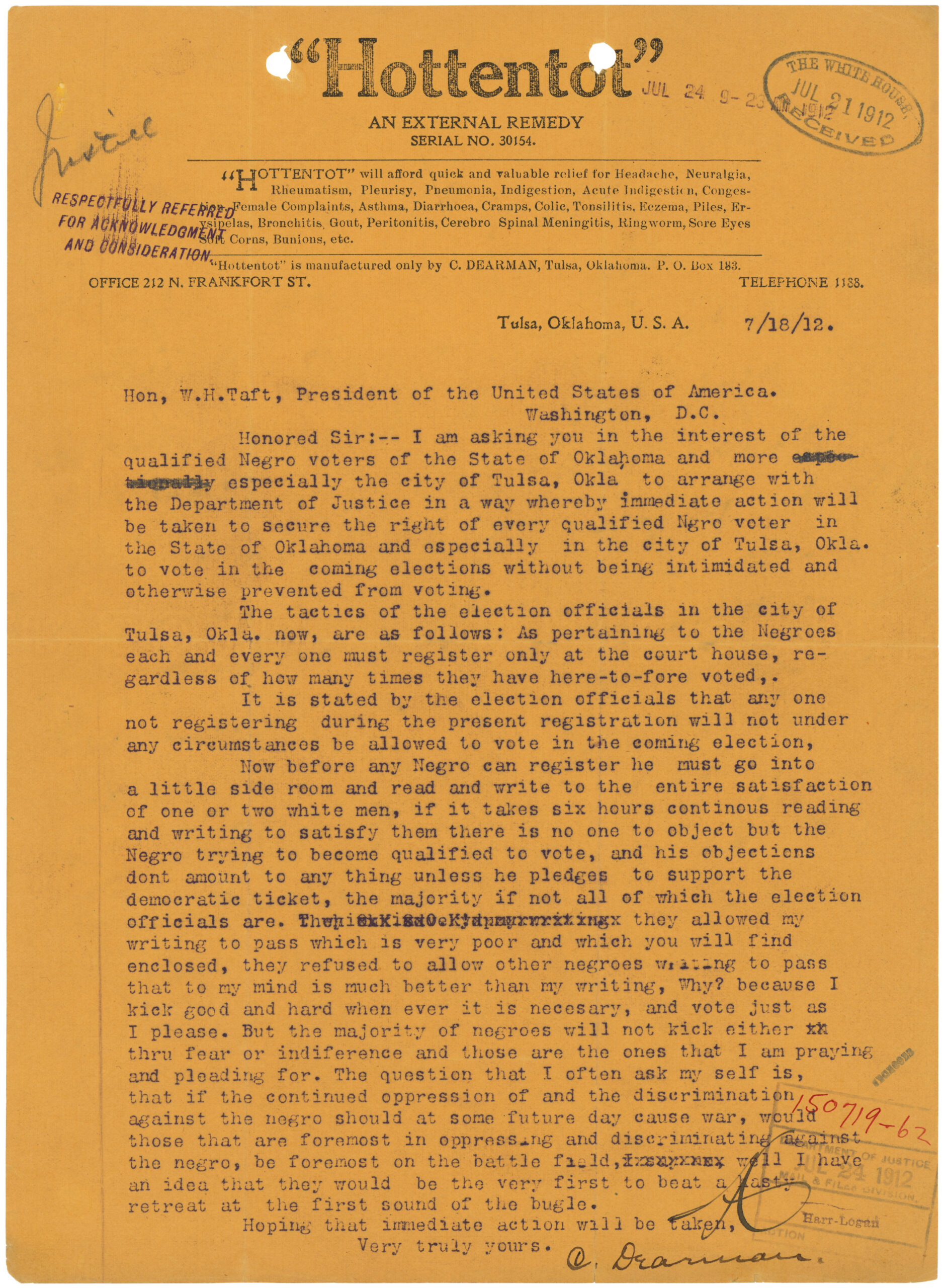

Nevertheless, determined Black men persisted in their determination to exercise their right to the franchise. On July 18, 1912, Mr. C. Dearman sent a letter to President William Howard Taft complaining about the conduct of the election officials in Tulsa, Oklahoma, who required him to pass a literacy test that took six hours. “[T]hey allowed my writing to pass which is very poor and which you will find enclosed, they refused to allow other negroes waiting to pass that to my mind is much better than my writing, Why? because I kick good and hard whenever it is necessary, and vote just as I please.” Mr. Dearman wrote to the president asking for his help in abolishing the literacy tests in Tulsa. Sometimes, we have to kick good and hard to secure our rights.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

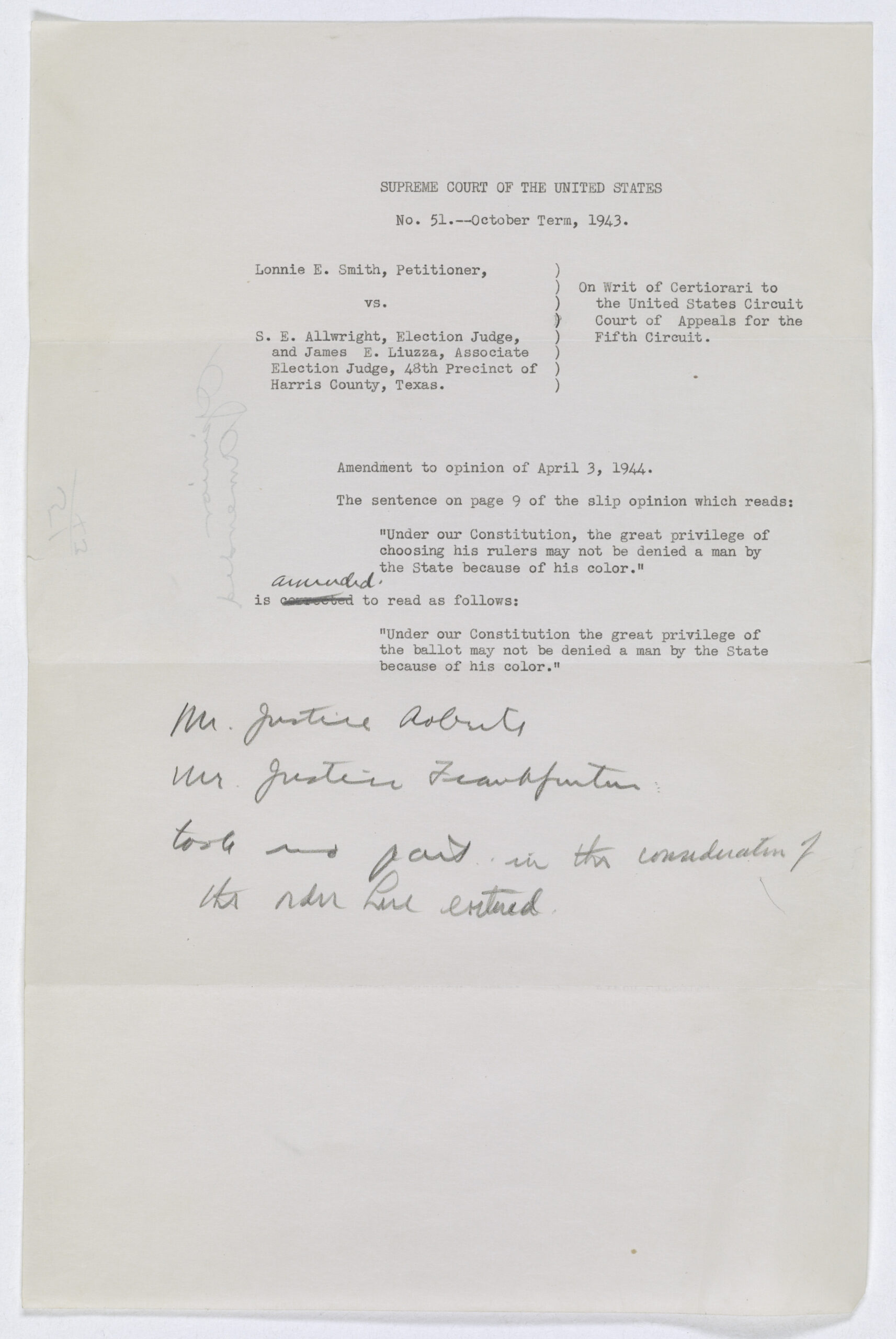

Success Realized

Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin was a Métis/Turtle Mountain Chippewa who spent her entire life advocating for Native American rights. She was born in 1863 on Ojibwe land that later became part of North Dakota. The family moved to Minnesota in 1867, where Marie attended public and Catholic schools and her father practiced law. She was briefly married to a businessman, Fred S. Baldwin, during this period.

Bottineau Baldwin moved with her father, J. B. Bottineau to Washington, D.C., to defend the Turtle Mountain Chippewa Nation’s treaty rights in the early 1890s. She clerked for her father in his law offices while he did this important work, and when it was done, they decided to stay in the capital city.

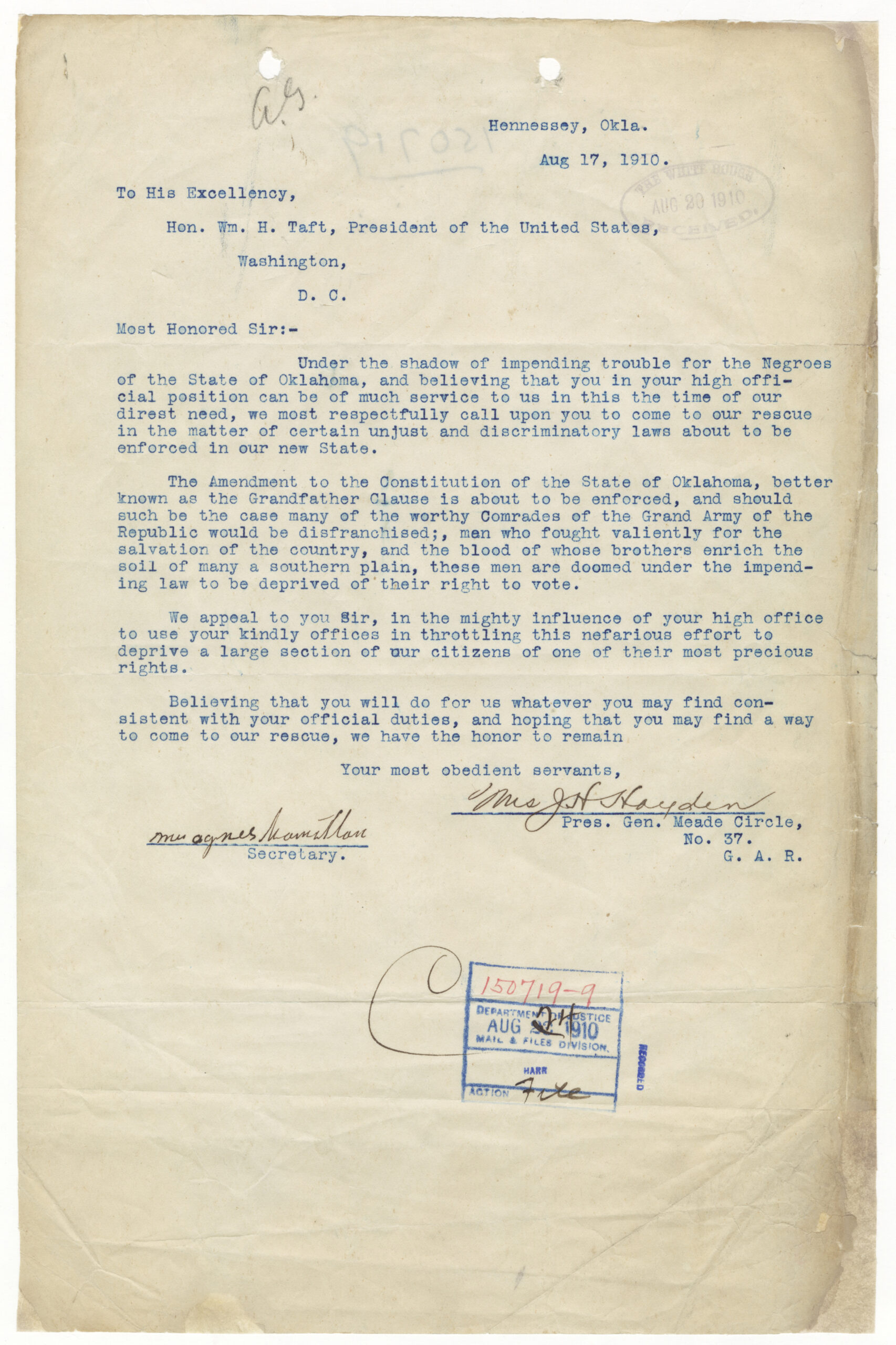

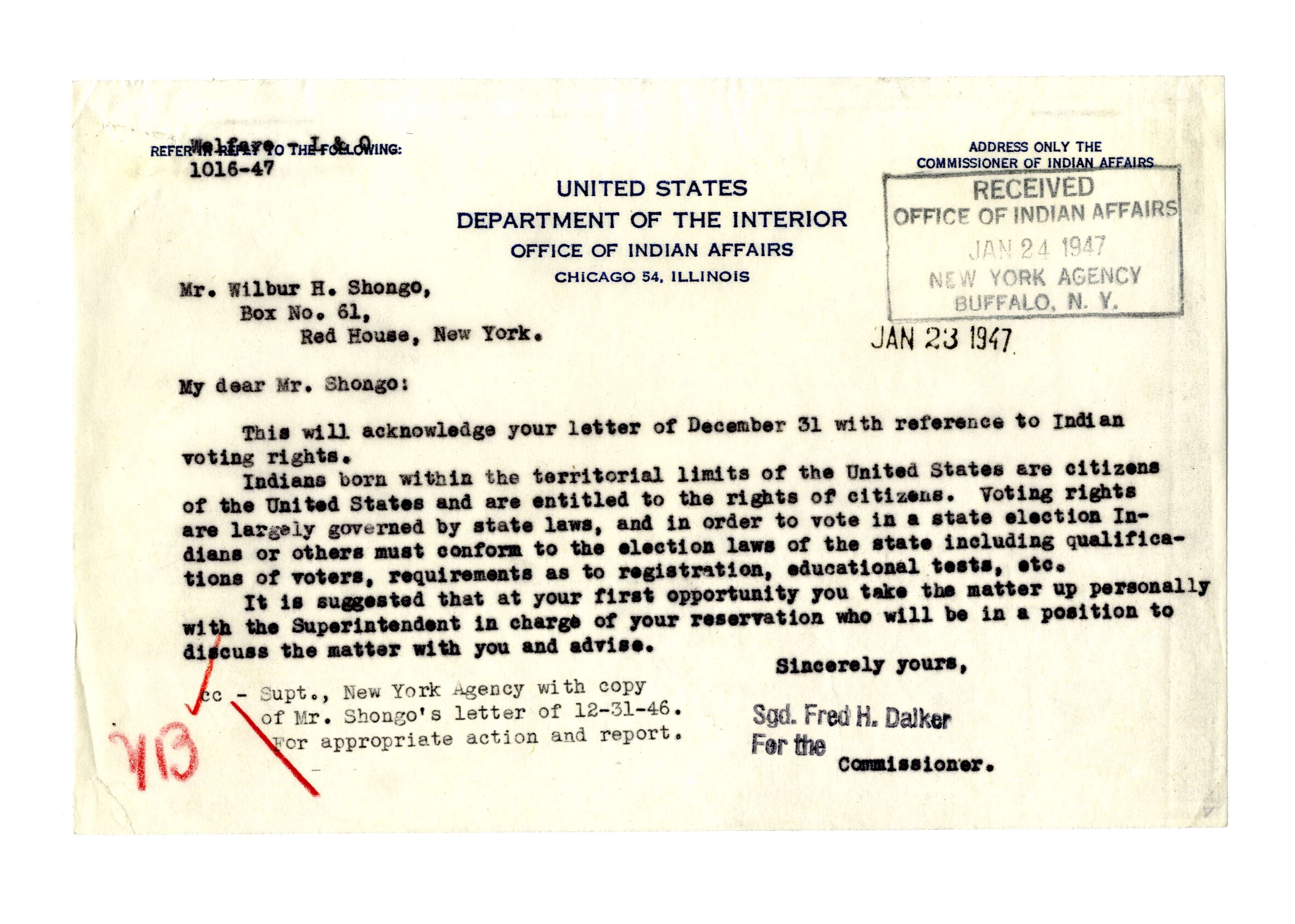

Letter answering questions about Indigenous voting rights

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Bottineau Baldwin to a clerkship in the Office of Indian Affairs in 1904. Although she had once thought that Indians should assimilate into white culture to survive, her attitudes changed the longer she lived in Washington. In 1911, when she had her photograph taken for her government personnel file, she braided her hair and wore Native dress.

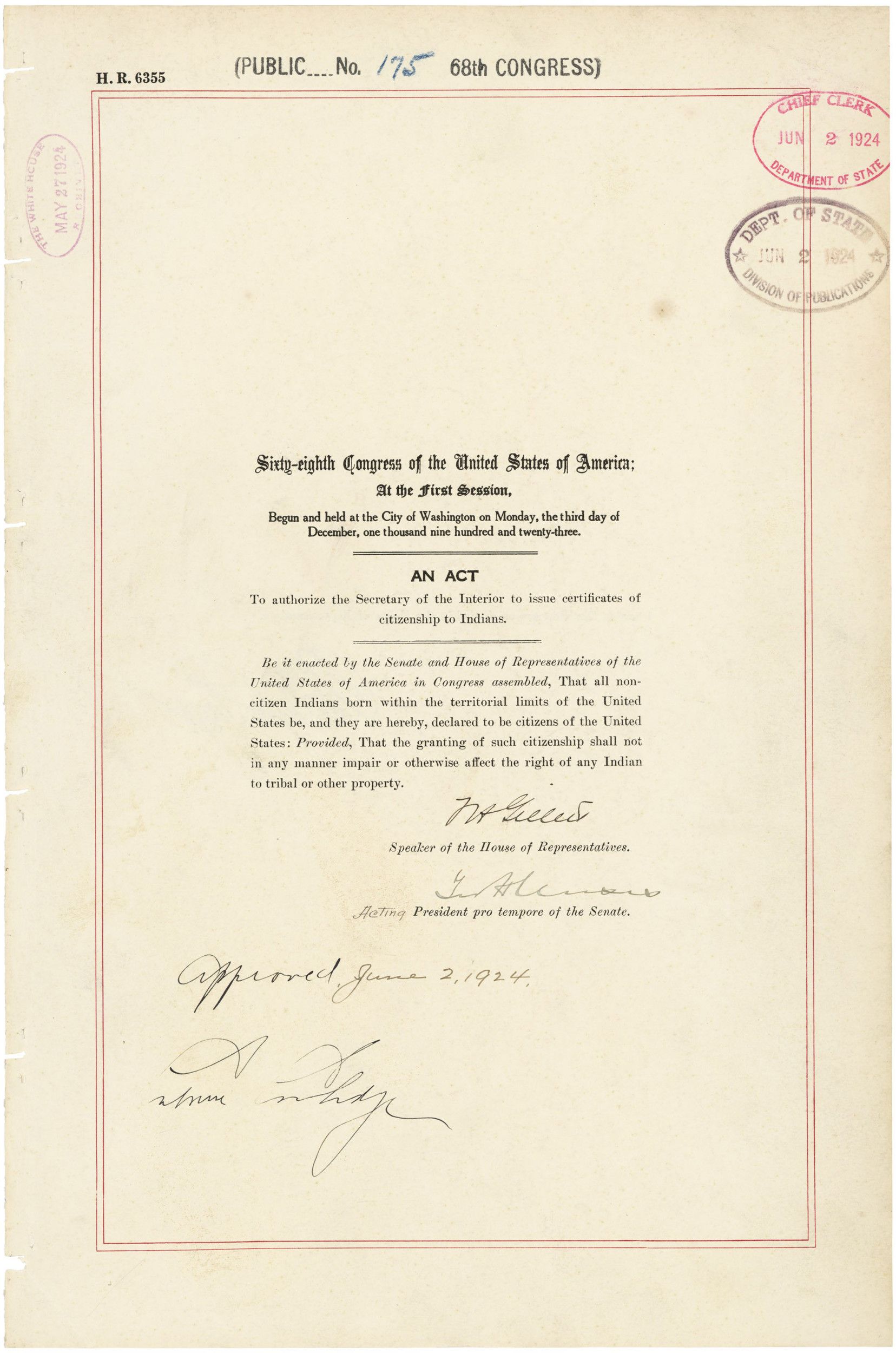

Indian Citizenship Act (1924)

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

A year later, her father died, and Bottineau Baldwin enrolled in the Washington College of Law at the age of 49. She completed the three-year course of study in two years, the first woman of color to graduate as an attorney. She became increasingly involved with the Society of American Indians and with the twin movements for Indian and women’s suffrage. She marched in the 1913 Suffrage Parade that Alice Paul, the women’s rights activist and feminist, organized in Washington. She became a spokesperson and an educator on the subject of the traditional political roles that Native women played in their societies as well as the role of modern Native women in American life.

Bottineau Baldwin lived to see both women’s suffrage and Native American suffrage become the law of the land. In 1949, she moved to Los Angeles, where she died in 1952. She is buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California.

Pay to Play

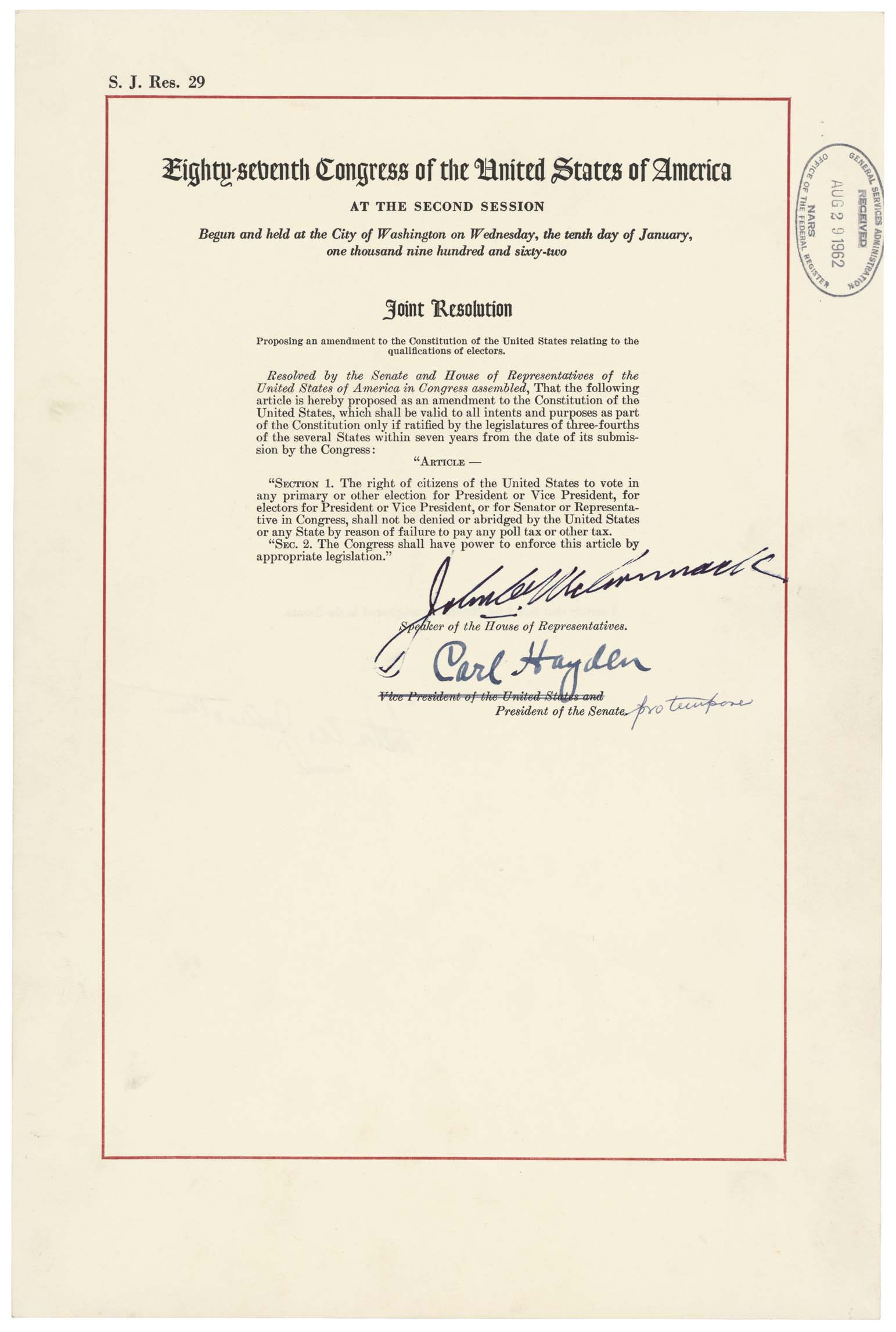

24th amendment

Congress passed the 24th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States on August 27, 1962, and the states ratified it on January 23, 1964. Its two sections read: “Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote in any primary or other election for President or Vice President, for electors for President or Vice President, or for Senator or Representative in Congress, shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State by reason of failure to pay any poll tax or other tax. Section 2. The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

After Reconstruction ended in the Southern states, poll taxes became a favored mechanism for preventing Black Americans from voting. Poll taxes were a workaround to subvert the 15th Amendment, which specifically gave the vote to Black Americans. Once they were implemented, poll taxes were levied on all voters, but they weighed most heavily on Black and poor voters.

Breedlove v. Suttles – SCOTUS upholds poll tax

NARA’s Records of Rights

Poll taxes were in effect in all of the former Confederate states by 1902. The federal government ignored them for years, until 1937, when a Georgia man, Nolan Breedlove, challenged the constitutionality of the poll tax in that state. In Breedlove v. Suttles, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the “privilege of voting is not derived from the United States, but is conferred by the state and, save as restrained by the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments and other provisions of the Federal Constitution, the state may condition suffrage as it deems appropriate.”

In the meantime, the poll tax was also being used to stop not only Black Americans and the poor, but also specifically women from voting.

It took several more tries and another quarter of a century, but the 24th Amendment finally put a stop to the practice of charging people a poll tax for the privilege of exercising their constitutional right to vote.

Barnyard Party

Berryman cartoon – “They won’t agree on anything!”

The Democratic donkey and the GOP elephant are staples seen in every election season. But where did they come from?

The donkey was first associated with Andrew Jackson’s campaign for president in 1828. Not liking Jackson’s policies, the opposition called Jackson an insult often associated with the donkey. But instead of getting upset, he embraced his haters and made light of the situation. The donkey was solidified as the Democrats’ mascot in the 1870s, when it was popularized by cartoonist Thomas Nast.

The GOP elephant has two origin stories. Soldiers used to refer to combat as “seeing the elephant,” and the elephant was first used to represent the GOP in a Civil War-era cartoon. After the war, Republican President Ulysses S. Grant was rumored to be running for a third term, and in a cartoon portraying various parties as animals, the elephant was once again as a representative of the GOP.