Back to School

It started around 7:50 a.m. yesterday. It was a hum that turned into a low roar. I opened my front door to see about 60 students and parents all amped up for the first day of school. Apparently, my street corner had become the destination for not one, but two new school bus stops.

When the first bus pulled up, the crowd burst into cheers and applause. (I think that was mostly the parents and not the petrified kids.) We each carry memories of those “first days.”

The Archives is full of our nation’s memories, and today we share a few educational gems in our back-to-school edition. Whether it’s the first day of kindergarten or the first walk into the lecture hall of college, these historical records give us a glimpse of schools of the past, from early efforts to educate girls and women, to a lawsuit that addressed integration before Brown v. Board of Education, to our kids’ favorite “subject” : lunch!

Sharpen your pencils! It’s time for you to take notes.

Watch the recording

Apollo 15 at 50: NASA’s Lunar Past & Future

📝

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Remembering 9/11

P.S. Looking for educational events from the Archives? Join us TOMORROW night to learn more about the Apollo 15 mission and the lunar rover and next week to commemorate the 20th anniversary of September 11th.

Suing for School

In the past hundred-plus years, the outcomes of several lawsuits have dramatically affected the way public education is conducted in the United States. One early lawsuit was Tape v. Hurley, which Joseph and Mary Tape filed in 1884 in San Francisco on behalf of their daughter, Mamie.

The city of San Francisco had supported a school for Chinese children from 1859 until 1870, when the district stopped mandating the education of Chinese students entirely. At that time, Chinese children born in the U.S. were not citizens. The Tapes tried to enroll their daughter in the all-white Spring Valley School, but officials would not let her attend classes there because she was Chinese.

Amending America: the 14th Amendment

Source: NARA’s Pieces of History blog

The Tapes sued the district, and in 1885, the California Supreme Court ruled that Mamie Tape and all other children of Chinese parents had the right to a public education. The state retaliated by passing legislation that established a school for Chinese students in San Francisco and then barred them from attending any other public schools.

On the surface, Plessy v. Ferguson might not have been explicitly about school segregation, but it was the lawsuit that established segregation as the law of the land in the United States. Homer Plessy, a Black man, was arrested in 1892 for boarding a “whites-only” train car in Louisiana. He pled not guilty, arguing that the Louisiana segregation laws violated the fourteenth amendment, which protected the citizenship of everyone born or naturalized in the U.S. and guaranteed them due process of the law.

The court convicted Plessy, but he appealed his case all the way to the Supreme Court. In 1896, the court upheld the lower court’s decision, stating that the fourteenth amendment did not mandate elimination of all “distinctions based upon color.”

This ruling gave states license to enact laws that segregated all manner of public accommodations, including hotels, hospitals, and schools. Plessy v. Ferguson enforced segregation in public schools for more than sixty years.

Brown v. Board of Education Anniversary

This post on the anniversary of Brown explores the depth of the inequity this decision created, especially in schools. In public schools as well as private spaces, Black individuals experienced not only physical separation, but also subpar accommodations.

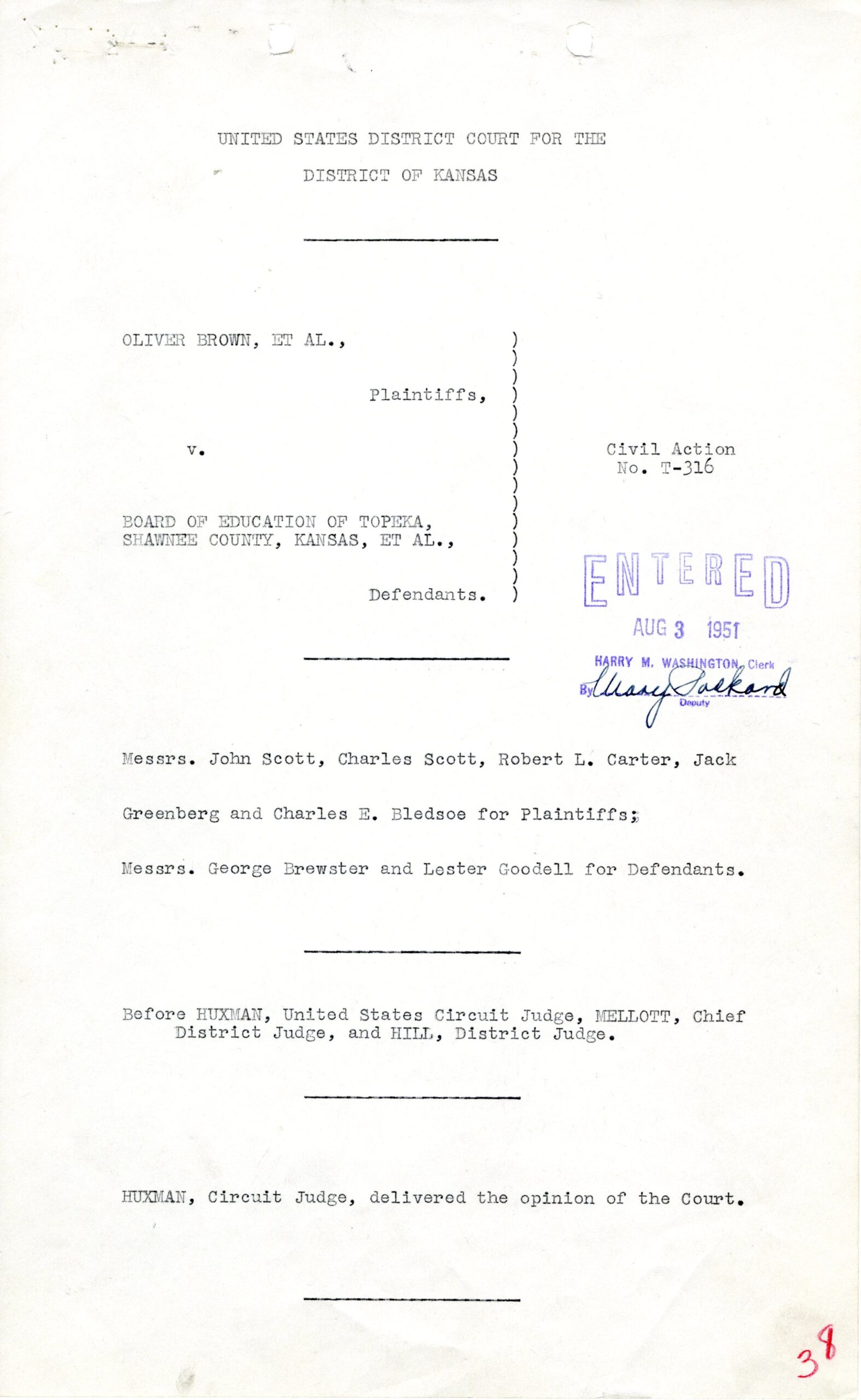

That changed on May 17, 1954, when the Supreme Court issued its opinion in the lawsuit Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. Brought by Mr. and Mrs. Oliver Brown and twelve other Black families in Topeka, Kansas, the class action suit alleged that schools for Black children in Topeka did not provide the same level of education as did schools for White children. The court ruled that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” which ended legal segregation of public schools in the country.

Opinion in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

National Archives Identifier: 2641494

Biographies of Key Figures in Brown v. Board of Education

Source: NARA’s Educator Resources

Opposition to the decision was immediate and widespread, particularly in the Deep South. When local and state officials persisted in dragging their feet in desegregating public schools, four years after handing down its decision in Brown, the court reaffirmed its opinion in Cooper v. Aaron (sometimes called Brown II) and ordered school districts to desegregate “with all deliberate speed.”

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka is also important because it bolstered the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, which became a force to be reckoned with in the coming decades.

A 1974 lawsuit addressed the matter of busing students to desegregate public schools. In Detroit, Verda Bradley, on behalf of her two sons, several other parents of children attending public school there, and the NAACP filed Milliken v. Bradley (summary), alleging that a state law had deliberately created segregated school districts. The court agreed with the plaintiffs and ordered that the city of Detroit develop a plan for desegregating all the schools that incorporated the outlying suburban school districts. Such a plan would require busing students to different schools, sometimes over long distances.

Ronald Bradley, et al. v. William J. Milliken, et al., 1970-1989

National Archives Identifier: 7788660

The defendants appealed the case to the Supreme Court, which overturned the original decision, stating that the suburban school districts had not conspired to keep Detroit’s public schools segregated.

The Little Rock 9: Where Are They Now?

On the heels of the Supreme Court’s rulings in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka and Cooper v. Aaron, the NAACP chose nine high school students, Minnijean Brown, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Thelma Mothershed, Melba Patillo, Gloria Ray, Terrence Roberts, Jefferson Thomas, and Carlotta Walls, to be the first to enter Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. The students were chosen for their personal determination and strength and then were extensively counseled to prepare them for the opposition they would face in their new high school.

On the first day of school, September 4, 1957, the nine students arrived at the high school and were turned away by members of the public and the Arkansas National Guard, whom Governor Orval Faubus had ordered to keep the students from entering the school building. A tense standoff ensued while federal judge Ronald Davies pursued legal action against Faubus and President Dwight D. Eisenhower tried to persuade the governor to change his stance. Finally, on September 20, the judge ordered the National Guard to disperse. The Little Rock police force escorted the nine students into the building on September 23, but they removed the students later that same day for their own safety. The next day, Eisenhower sent members of the 101st Airborne Division of the Army to Little Rock to maintain order. On September 25, the students were finally able to attend school for the first time. Throughout the school year, they endured harassment, hate speech, and physical violence.

These students have become known as the Little Rock Nine. Nearly ten years after they entered Central High School, the National Archives produced a short film titled Nine from Little Rock about them and their accomplishments after they left high school. In 1998, Congress awarded all nine with the Congressional Gold Medal, Congress’ highest award for distinguished achievement.

Nine from Little Rock, 1964 – Restored

(18 minutes 30 seconds)

Source: NARA YouTube Channel

A Teacher Who Remembered the Ladies

Emma Willard was a lifelong proponent of education for girls and women. Story: In the United States, the history of public education is also a history of the fight to expand opportunities for underserved populations to go to school. One notable individual who took the fight to extremes was Emma Willard.

Emma Hart Willard was born in Berlin, Connecticut, in 1787, just a few months before the Constitutional Convention convened in Philadelphia. She was fortunate – in an era when women were rarely educated beyond the basics, her father, a farmer, recognized her aptitude for learning and encouraged her (and his other, numerous children) to study to reach their full potential.

Willard taught herself geometry when she was thirteen. She then enrolled in the Berlin Academy, and within two years, she was teaching there. Next, she got a teaching job at a girls’ school in Middlebury, Vermont. Her experiences there moved her to open the Middlebury Female Academy, a boarding school for girls, in 1814.

Throughout her career, Willard lobbied constantly and tirelessly for women’s education. She petitioned the governor and legislature of Vermont for financial support for schools for girls, but they rejected her pleas. She then moved to New York, where she also met with stubborn opposition. However, in 1821, officials in the small town of Troy, New York, agreed to levy a special tax to establish the Troy Female Seminary. The school created a rigorous and comprehensive curriculum for female students in grades nine through twelve as well as post-graduate study. Willard served as head of the seminary until 1838. She died in 1870 in Troy. In 1892, the school was renamed “Emma Willard School” in her honor.

The Emma Willard School has been in continuous operation since its establishment and is widely regarded as one of the best girls’ schools in the country. Over the past 200 years, it has consistently turned out highly successful alumnae – Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the great American suffragette, and actress Jane Fonda studied at Troy.

One of Willard’s innovations was permitting students who could not afford the school’s fees to attend on the condition that upon their graduation, they would become teachers themselves. This was a ground-breaking action that produced many female teachers at exactly the time when they were increasingly in demand in the United States.

Thomas Jefferson to Emma Willard, 18 December 1819

Source: NARA’s Founders Online

From John Adams to Emma Willard, 11 May 1821

Source: NARA’s Founders Online

Throughout her life, Willard corresponded with important individuals, including Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, about her driving conviction that women should be educated as well as men were. The National Archives preserves many such letters in its holdings.

History Snacks

Textbook History

Brothers William Holmes McGuffey and Alexander Hamilton McGuffey were the brain trust behind the McGuffey Readers, a series of books for grades 1 through 6. Between 1836 and 1960, more than 120 million copies of the readers were sold, making them among the most influential textbooks used in the United States.

Remarks Announcing the Resignation of William J. Bennett as Secretary of Education and the Nomination of Lauro F. Cavazos

Source: Reagan Library

The Cincinnati-based publishing house of Truman and Smith approached William McGuffey, a college professor, to create a set of readers for primary school children. He wrote the first four books in the series, and his brother Alexander wrote the fifth and sixth books.

The McGuffey Readers helped millions of students learn to read and write. They were, however, definitely products of their time, showing a strong Protestant religious bent and perpetuating many myths as historical fact, such as the story of George Washington and the cherry tree. Their influence was unmistakable – when William Bennet resigned his position of Secretary of Education, President Ronald Reagan extolled him as “the best thing to happen to American education since the ‘McGuffey Reader.’”

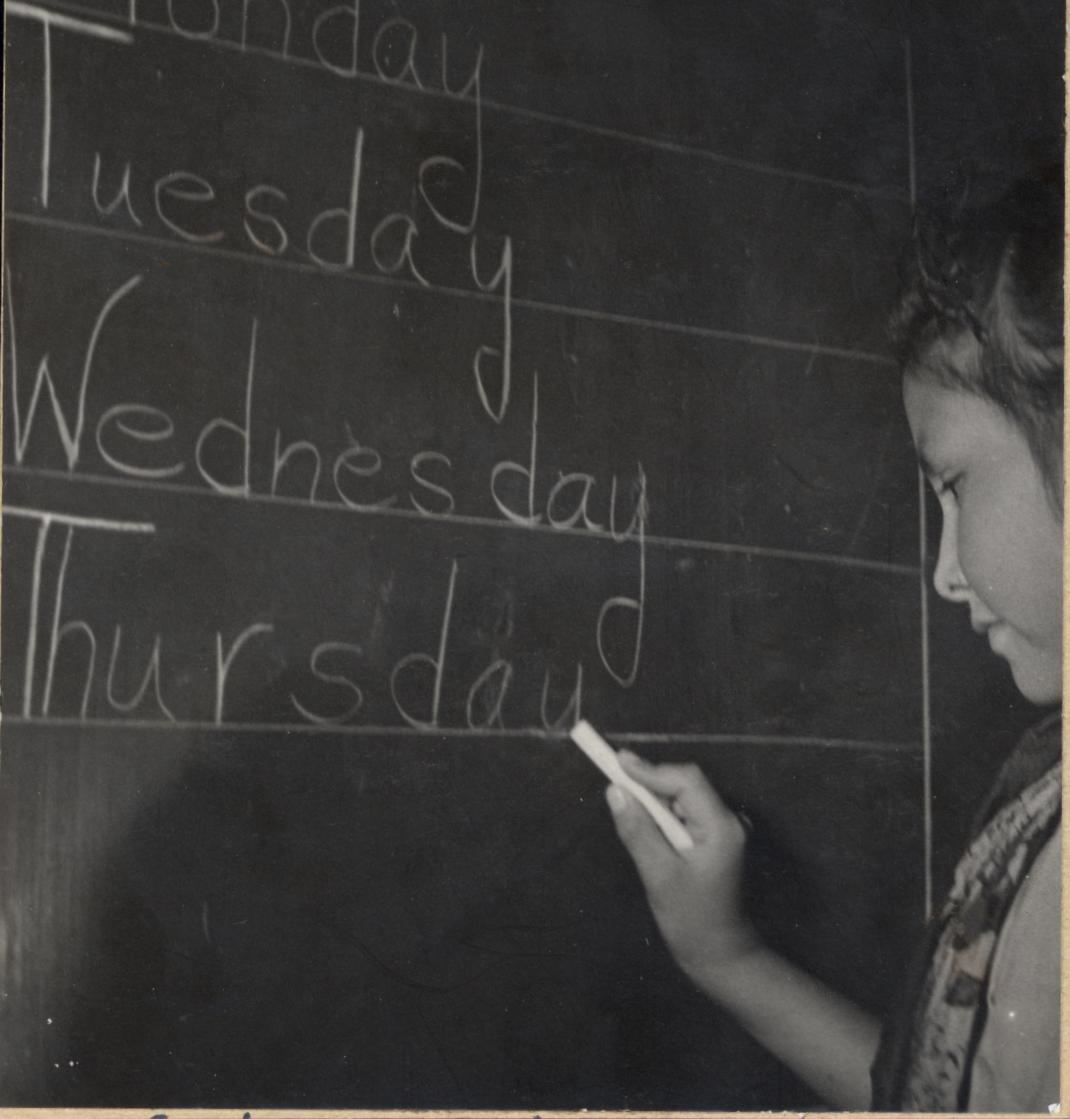

The Lunch Bell

Time for (school) lunch

The Federal National School Lunch Program began in 1946. It provides nutritionally balanced meals in both public and private schools across the country. The program was started in 1946, “as a measure of national security to safeguard the health and well-being of the Nation’s children and to encourage the domestic consumption of nutritious agricultural commodities and other food…”

Children whose families meet certain criteria are eligible to receive free or reduced-price lunches. In 1966, the Child Nutrition Act expanded eligibility and added school breakfast programs, while both Presidents Eisenhower and Nixon increased budgets for school lunch programs to provide kids with filling, nutritious lunches.

In the 1980s, school meal programs became subjects of controversy, and they have remained so until the present day. That’s why it’s vital to understand the once-noncontroversial history of school lunches because the program is now responsible for feeding more than 31 million children every day.