Considering a New Narrative

“In fourteen-hundred ninety-two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue” is a simple rhyme that I heard from my dad and that he learned in school. (He definitely experienced more poetic teaching. He had learned all sorts of rhymes and songs to remember facts and figures – and he never forgot them.)

While we may remember that date, our collective understanding of the long and complex history of those who Columbus and other settlers encountered, the cultures he discovered in the “New World,” and what followed have often been obscured.

Like most U.S. citizens, I don’t have a great command of Native American history, but I’ve come across many eye-opening facts and documents that have reset my assumptions and started to fill this shortcoming.

Over the past few years, history and civic institutions, including the Archives, have sought to broaden our story of discovery to include a better understanding of the lives and contributions of Indigenous peoples to our nation’s history. One recent example is the Archivist of the United States’ act of acknowledging the relationship between the current day (the locations around the country where the Archives has facilities) and the past. You can read more about this series on his AOTUS Blog.

We work with the Archives to help the public form a more accurate picture of history, so this week, we’re opening up the records to learn about and celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Sovereign Nations

Transcript of the Constitution

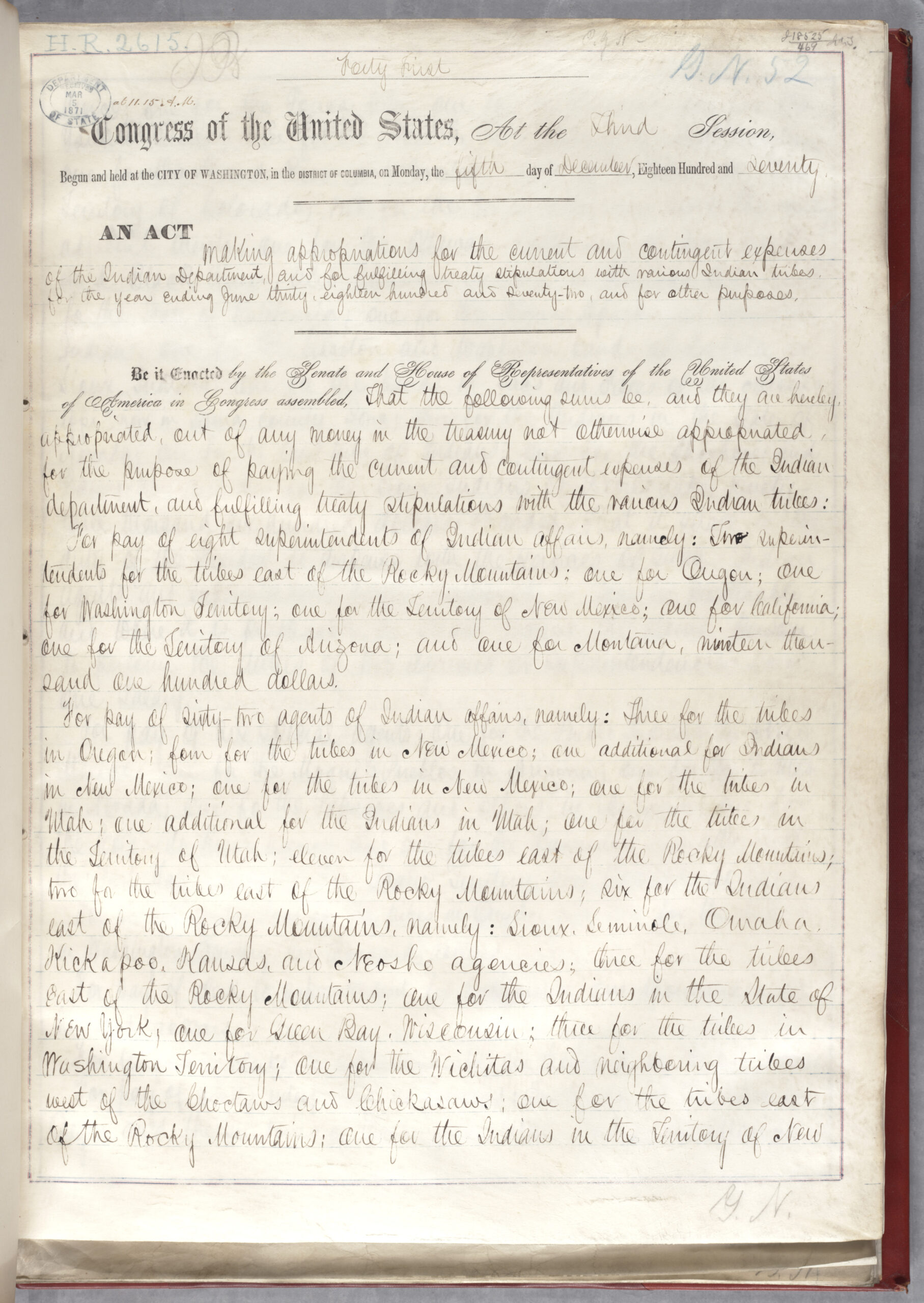

Article two, section two of the U.S. Constitution grants the President the power to make treaties, contingent upon the approval of two-thirds of the Senate, and article six declares, “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land. . . ” . From 1778 until 1871, the United States government made treaties with individual Indian tribes because it recognized them as sovereign nations. That stance changed in 1871, when the House of Representatives passed the Indian Appropriations Act, which stripped the tribes of their sovereignty.

The scope and efficacy of the treaties negotiated in that nearly 100-year span were checkered, to say the least. In many cases, the rights of Native Americans were explicitly spelled out in treaties, only to be negated by a lack of enforcement (sometimes intentional) on the part of the government or by later treaties that more severely limited Indian rights, especially to their ancestral lands.

Digitreaties, an online search tool to explore Native American treaties

Hundreds of treaties are available on Digitreaties. The Archives also hosts a virtual exhibition titled Rights of Native Americans, part of its Record of Rights series, that describes the struggle for Native American rights from the first treaty between the nation and a Native tribe through the passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1978. It features many of the most important primary sources that document the erosion of Native rights in the U.S.

A Grave Injustice

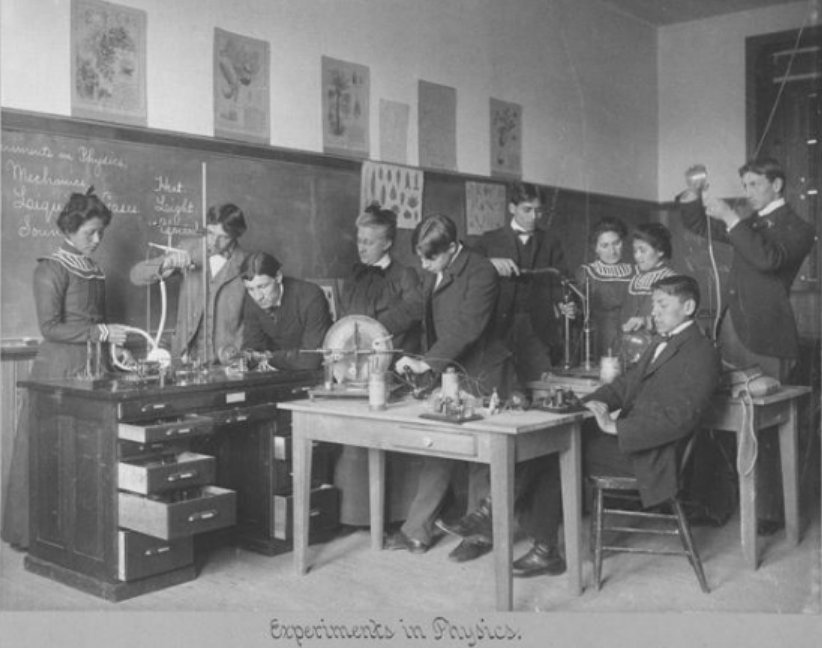

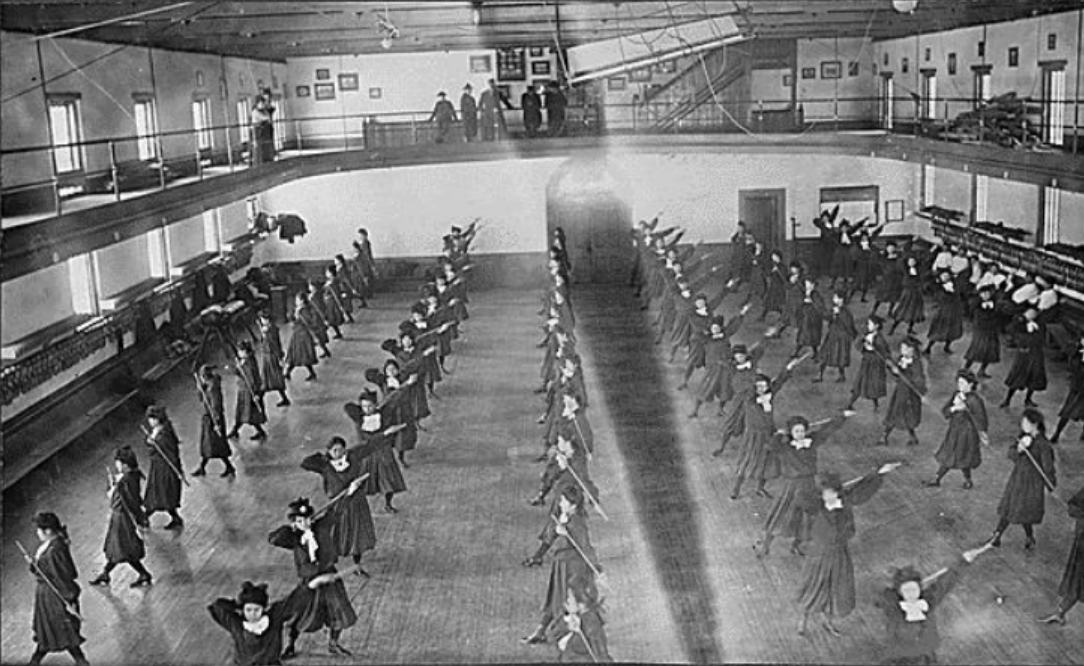

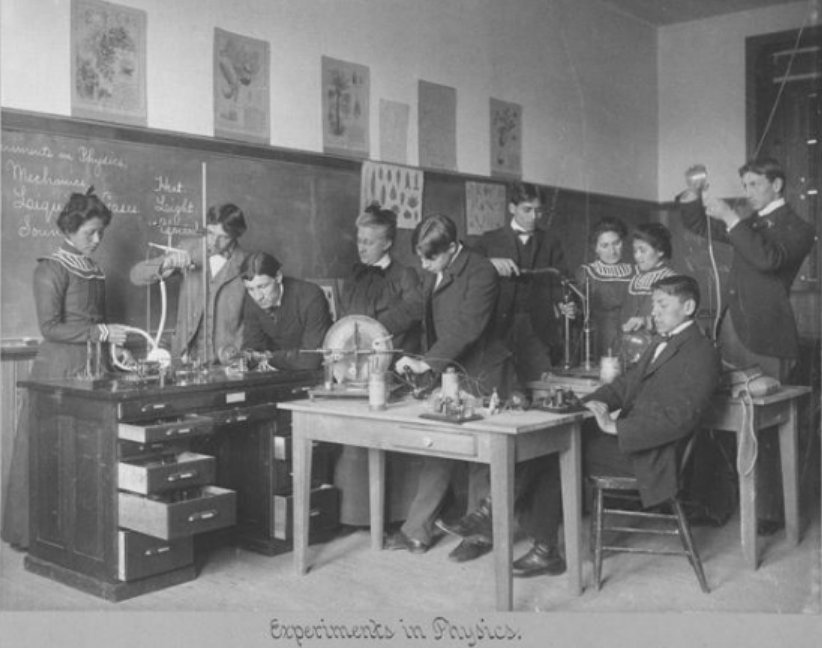

Probably the cruelest tool in the effort to force Native Americans to assimilate into the mainstream Euro-American society was the Indian boarding school. Under the terms of many treaties negotiated between the tribes and the U.S. government, the latter was obliged to provide education for Native children. The boarding schools of the nineteenth century, however, took this obligation to more sinister heights.

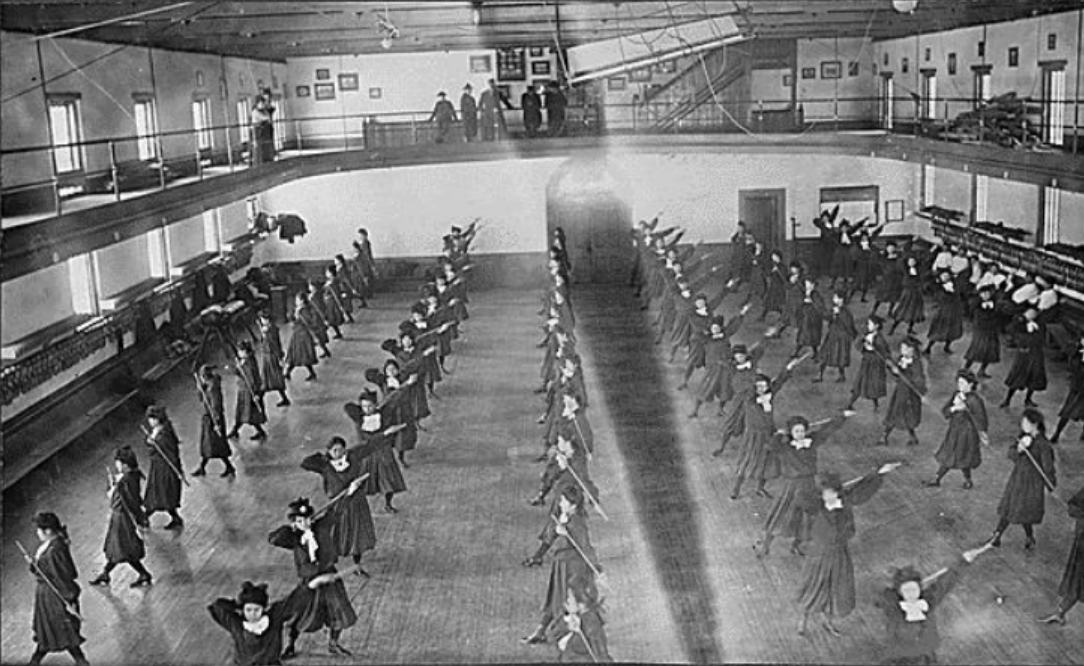

After the Indian Wars ended in the West in the late nineteenth century, many religious denominations opened residential schools for Indian children on reservations. Children were often forcibly removed from their homes and taken to the boarding schools, where their hair was cut, their clothes were taken from them and replaced with uniforms, and they were forbidden to speak their Native languages or practice their religion. Bent on “civilizing” the children, the schools taught a Euro-American style education and deliberately aimed to destroy the children’s connections to their cultures. As time passed, more boarding schools were opened off the reservations, often far from the children’s homes.

Arguably the best-known of the U.S. Indian boarding schools in the United States Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, founded in 1879 by Lieutenant Richard Henry Pratt. A Civil War veteran, Pratt had previously supervised the Native prisoners of war at Fort Marion, Florida. Based on his experiences there, Pratt created the mantra, “Kill the Indian, save the man.” It became the guiding principle of the Carlisle school.

Unfortunately, those words often proved prophetic in the worst possible way. Many Indigenous children died of infectious diseases like tuberculosis while they were in the custody of the residential schools, both in the United States and Canada. To make matters worse, it was not uncommon that their families were not notified of the children’s deaths.

In early summer 2021, nearly 800 unmarked graves were discovered at Indian boarding schools in Canada. Shortly thereafter, the remains of nine Rosebud Sioux children were located on the grounds of the Carlisle school. In late summer 2021, the remains were returned to their tribe in South Dakota, where they were interred.

In response to these developments, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, herself an enrolled member of the Laguna Pueblo in Arizona, has opened an investigation into Indian boarding schools.

The Road to Suffrage

Act of June 2, 1924, … which authorized the Secretary of the Interior to issue certificates of citizenship to Indians.

Source: NARA’s America’s Historical Documents

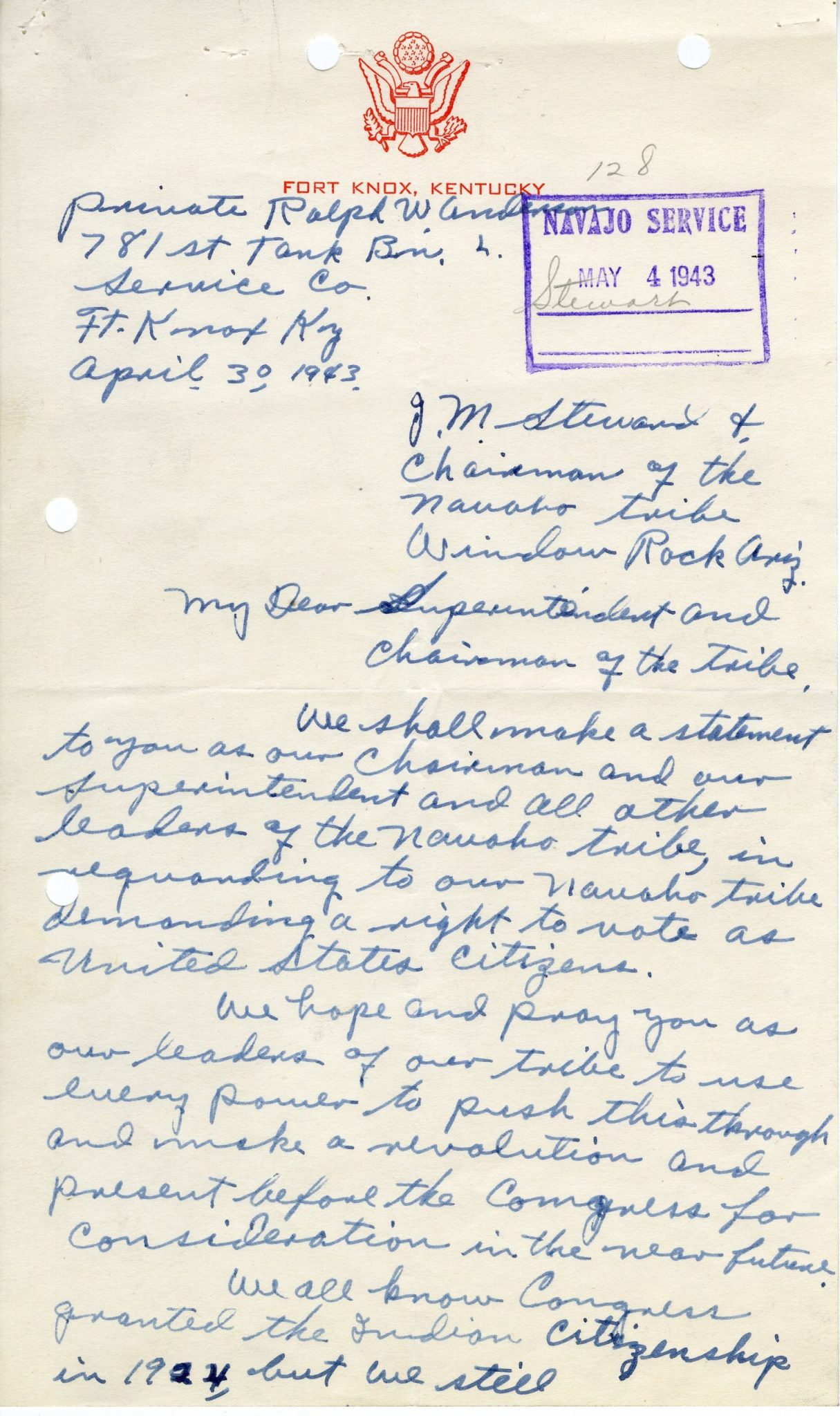

After World War II ended, Native American veterans led a different fight to secure their right to vote. On several occasions, Native veterans in New Mexico and Arizona attempted to register to vote and were turned away by public officials. Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the holdings of the National Archives at Denver, Colorado, illuminate this story.

The War after the War: the American Indian Fight for the Vote after WWII

in The Text Message

The question of whether Native Americans had the right to vote has been long and contentiously debated at the state and federal levels. It was not until 1919 that World War I veterans who had been honorably discharged were granted the right to vote regardless of their ethnicity. In 1924, all Native Americans were given citizenship, and consequently, the right to vote, but the reality on the ground, in state and county courthouses and polling places, often played out differently.

It was not until 1948 that Arizona finally agreed that Native Americans had the right to vote. New Mexico followed suit that same year. In 1957, the last holdout state, Utah, agreed to grant the franchise to Native Americans.

Native Sports: Lacrosse

The Greatest Athlete of the First Half of the Century

Source: NARA’s Pieces of History Blog

Lacrosse, that darling game of athletes across North America, evolved from several different types of stickball games that Native American and First Nations tribes played for centuries. The artist George Catlin, who traveled the American West five times in the 1830s, painted several portraits of Indians dressed to the nines and holding their stickball equipment. Native stickball games often went on for days on end and sometimes became rather violent. Over the past century, a toned-down version of the game has spread across the United States and Canada. It was an Olympic sport in 1904 and 1908, but it is no longer represented in the Olympics due to a decline in international participation.

Jim Thorpe, who was of Fox and Sauk extraction and who grew up in Oklahoma, is widely regarded as one of the greatest athletes of the 20th century. He is probably most famous for winning the Olympic gold medal in the decathlon in the Summer Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1912. But Thorpe was no one-hit wonder—he also played football, baseball, basketball and lacrosse.

Land Recognition

Native Land

Digital Maps

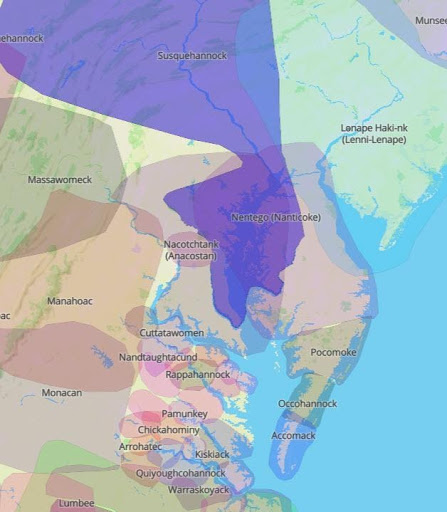

Much has been said and written about the U.S. government’s predatory treaty-making with Indigenous tribes from the founding of the nation up until 1871, but we should all recognize that every place in what is now the United States was once Native land. The Archivist of the United States, David Ferriero, is publishing an ongoing blog series about the Native lands that National Archives buildings stand on. For example, the Archives Building in Washington, D.C., sits on the ancestral lands of the Nacotchtank peoples. And you don’t just have to explore Archives facilities – the series features an interactive map that you can enter your address on to see what tribes originally inhabited the land you now live on.

Land Acknowledgement: The Importance of Acknowledging our History

Source: AOTUS Blog

October 12, 2021

Land Acknowledgement: The Importance of Acknowledging History

Source: AOTUS Blog

April 20, 2021