What I Didn’t Know.

About a year and a half ago, I was passed a memo listing the Tulsa Race Massacre. I immediately asked myself, “How have I never heard about this event between World War I and the Great Depression?” That question started me on a journey to learn more.

The Archives Foundation aims to not only be the evangelist of U.S history and the Archives, but to also bring to light the lesser known, recently discovered or untold stories of our nation’s past. Today is the 100th anniversary of one of the worst tragedies in American history. Last week and this week there have been countless documentaries, newspaper and magazine stories, blogs and announcements about this violent and destructive event in Tulsa. But a year and half ago, it remained largely unfamiliar to the general public.

The Personal

Mission of

Civil Rights Attorney

Fred Gray

View the recording

(1 hour 13 minutes 30 seconds)

from June 10, 2021

The Foundation commemorated the anniversary by hosting a virtual program last week that explored the details of the success of Black economies at the time, the tragic history of the Tulsa Race Massacre and the landscape Black entrepreneurs face today.

Next week we fast-forward in U.S. history to the Civil Rights movement. On Thursday, June 10, at 5 p.m. EDT, the Foundation will host an online conversation with attorney and Civil Rights icon Fred Gray. The interview will include his first-person account of the Montgomery Bus Boycott and his relationships with Rosa Parks, John Lewis and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. I hope you’ll register and join us.

The opportunity to discover our history knows no bounds. We are pleased to be one of the places you choose to let history reveal itself.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Our Black History Programming is made possible in part by the National Archives Foundation through the generous support of Ford Motor Company Fund.

Emancipation for All

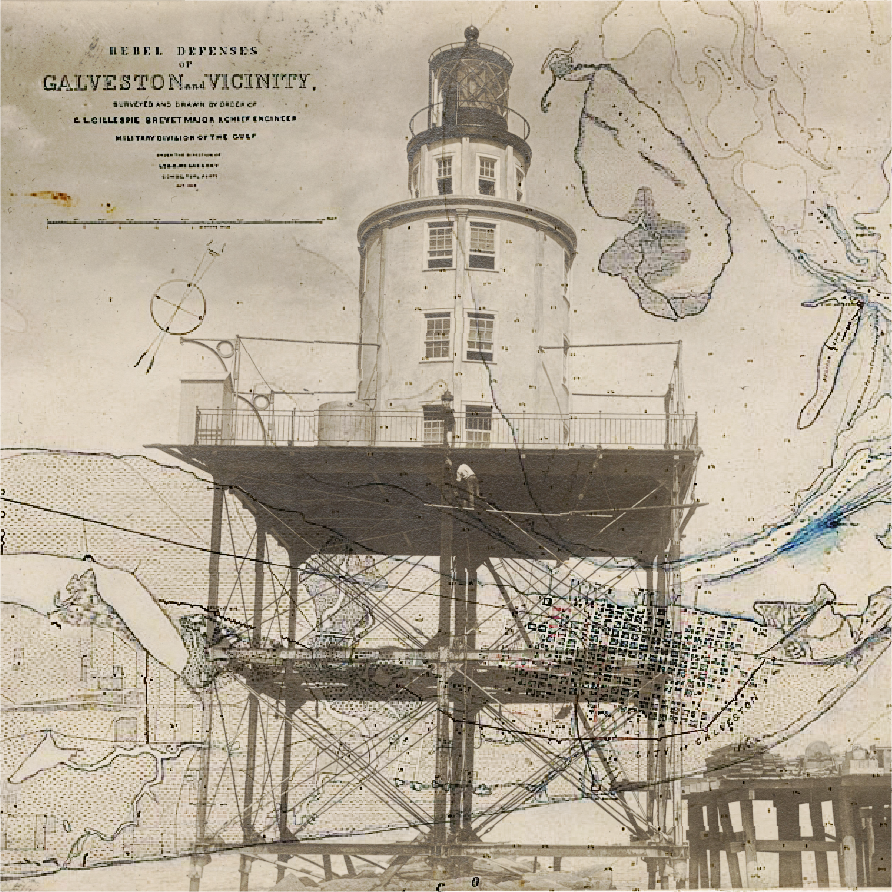

Rebel Defenses

at Galveston

June 19 is Juneteenth, which commemorates the day in 1865 that slaves in Galveston, Texas, were told that Abraham Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation that freed them. They received the news two and a half years after the fact, but that didn’t dampen their joy at learning they were free.

Starting on that day in Texas in 1865, Juneteenth was celebrated sporadically for nearly a century before the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement embraced it in the 1960s. Since then, an ever-growing number of states have recognized it as an official holiday.

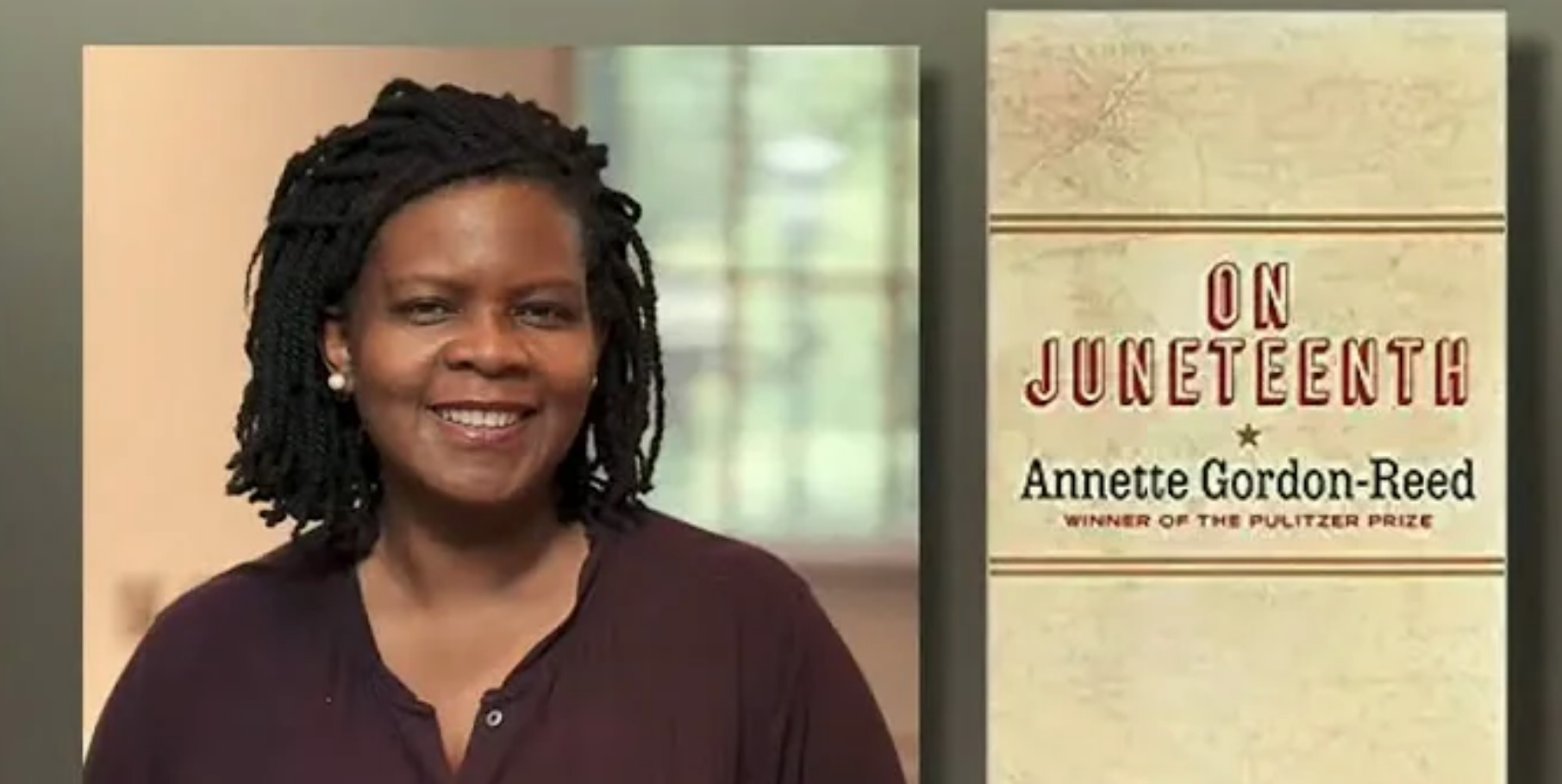

with Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Annette Gordon-Reed

View the recording

(1 hour 4 minutes 15 seconds)

from June 2, 2021

On June 2 at 7 p.m., the National Archives will host an online program titled “On Juneteenth” with Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Annette Gordon-Reed, Roy Young, CEO of James Madison’s Montpelier, and the Reverend Dr. Halliard Brown, Jr., a board member of The Orange County African-American Historical Society. The program is presented in partnership with James Madison’s Montpelier and made possible in part by the National Archives Foundation through the generous support of The Boeing Company.

Join us for what will be an engaging and educational discussion!

Black Wall Street: The Forgotten Tragedy

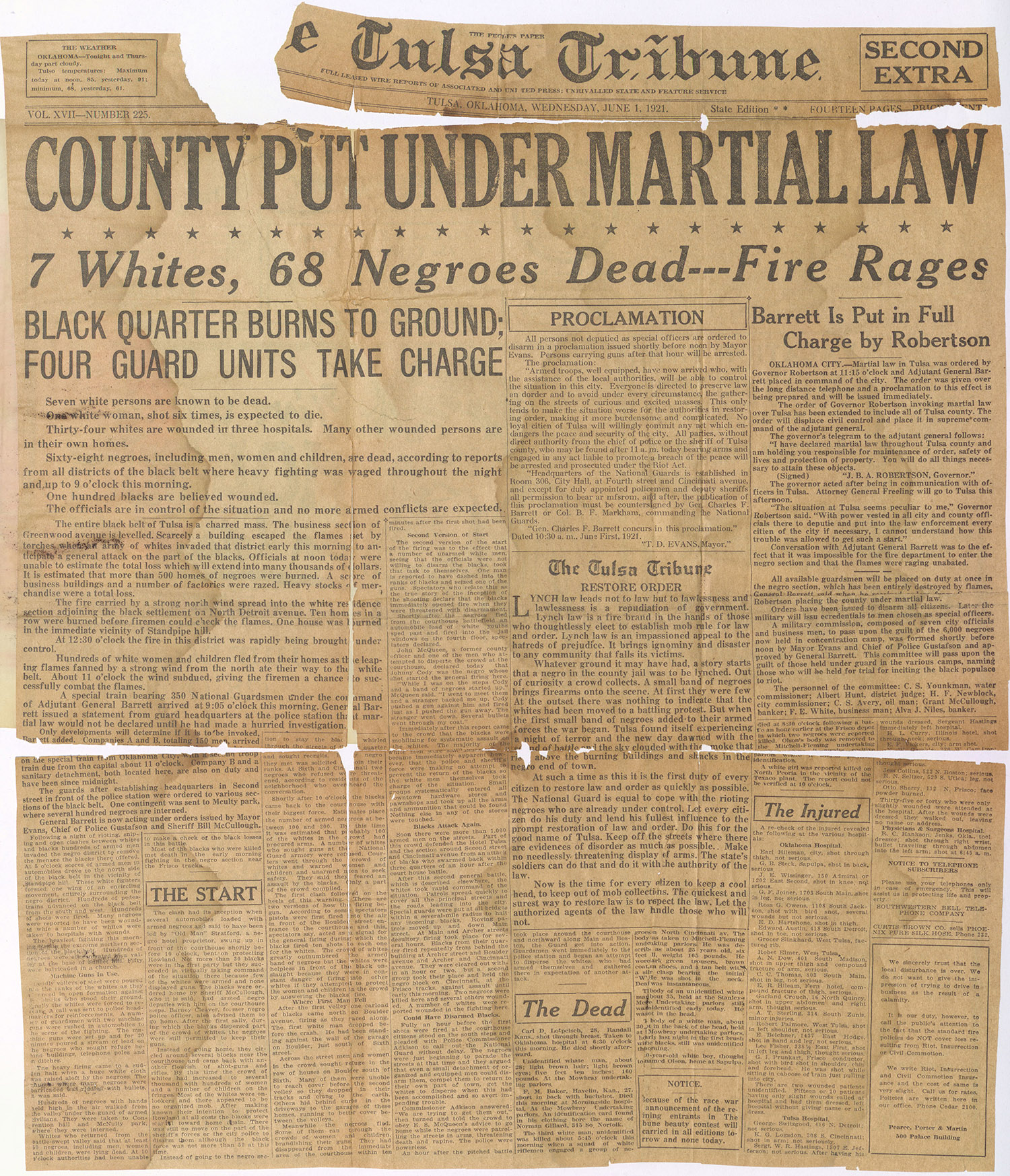

Newsclipping from the Tulsa Tribune

June 1, 1921

The Tulsa Race Massacre took place from May 31 to June 1, 1921, exactly one hundred years ago. Over that 24-hour period, white mobs attacked Black people and destroyed Black-owned businesses and property in the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma. The massacre was sparked by a report that a Black man, Dick Rowland, had assaulted a white elevator operator, Sarah Page, who later denied the claim.

The Greenwood district was well known as Black Wall Street, a business district that was home to the wealthiest Black community in the U.S. at the time. When the American Red Cross arrived in Tulsa the next day, they found that the area had been completely destroyed and 10,000 people needed their help. Rebuilding the district took more than 10 years.

Although it was widely and nationally reported at the time, the Tulsa Race Massacre faded from public awareness almost immediately. It was not until decades later that investigations were launched into the riots.

The National Archives has played an ongoing role in keeping this story before the public. On Wednesday, May 26, the Archives Foundation hosted an online conversation titled “Black Wall Street: The Hidden Economy” that featured A’Lelia Bundles, a historian, author and journalist, Ron Busby, President and CEO of the U.S. Black Chambers, Inc., and Tristan Wilkerson, Managing Principal of Think Rubix, LLC and General Partner of High Street Equity Partners.

The participants’ observations were profound and sobering. “Between 1870 and World War I, there were more than 100 towns in the West founded by African Americans. The Greenwood section of Tulsa was one of those towns. . . . ,” Bundles said. “[W]hen [my great-great-grandmother] Madam [C. J.] Walker arrived in Greenwood, she would’ve seen a thriving community. In the 100 block of Greenwood Avenue, there were more than 70 businesses: four hotels, two newspapers, eight doctors, a movie theater, seven barbers, a cigar store, nine restaurants, and a half-dozen professional offices. But as we all know, that neighborhood was destroyed in a horrendous massacre on June 1, 1921.”

The event ended noting that even until this day, Black Tulsans have never been repaid for the loss of life, property and trauma that they endured over those two days. Though many in the community were resilient and went on to rebuild their businesses, many others left Greenwood, with their sources of both immediate and generational wealth gone.

Here is the video if you missed the conversation or if you’d like to see it again.

Black Wall Street: The Hidden Economy (1 hours 7 min)

Freedom on Display

Exhibition Opening

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed enslaved people in the states that had seceded from the union. The proclamation also announced that Black men would be accepted into the Union army. Eventually, nearly 200,000 Black men fought on the Union’s side in the Civil War.

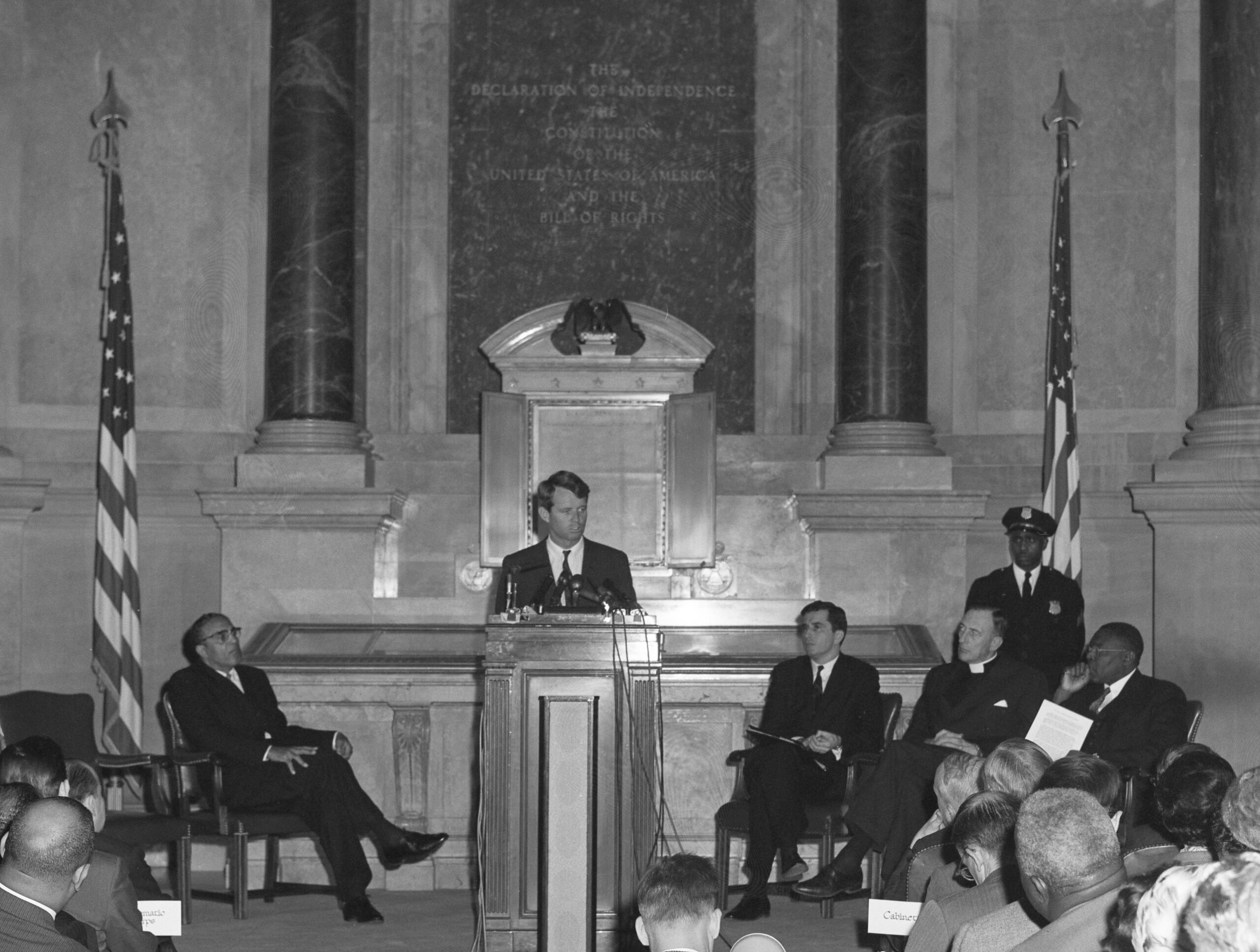

Attorney General Robert Kennedy at the Opening of the Emancipation Proclamation Centennial Exhibit

National Archives Identifier: 12170394

The Emancipation Proclamation is one of the most important documents committed to the care of the National Archives. It was featured in an exhibition commemorating the centennial of its issuance in 1963, when U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy presided at the exhibition opening. Other prominent civic leaders were also present and spoke, such as Charles H. Wesley (pictured), the President of Central State College. Because of the document’s fragility, it is not on display at all times, but it will be displayed at the Archives again November 19-21, 2021.

Online Exhibit

Revising the Record

Portrait of Dolley Madison

You may have heard that First Lady Dolley Madison saved Gilbert Stuart’s famous Lansdowne portrait of George Washington when the British invaded Washington, D.C., during the war of 1812. As British troops approached the White House on August 24, 1814, Dolley cut the canvas out of its frame and carried it to safety—or so the story goes.

Just how the portrait was saved is actually somewhat unclear. In his memoir “A Colored Man’s Reminiscences of James Madison,” Paul Jennings, who was James Madison’s valet and who was working at the White House that day, reported that John Susé, the doorkeeper, and Thomas Magraw, the President’s gardener, put the portrait in a wagon along with other valuables and carried them away.

From George Washington to Lansdowne, 7 November 1791

on Founders Online

In any event, after the war ended, the portrait was returned to the White House, where it is now on display. Stuart’s painting is called the “Lansdowne portrait” because William Bingham, a U.S. Senator from Pennsylvania, and his wife Anne commissioned it as a gift for British Prime Minister William Petty (1737–1805), the First Marquis of Lansdowne. A long-time supporter of American independence, the Marquis negotiated the Peace of Paris, the treaty between the United States and Great Britain that ended the Revolutionary War in 1793.

Dolley Madison Source: The Trump White House

Despite the doubtfulness of the story about Dolley Madison and the portrait, there is no doubt that she was one of the most vivacious and beloved First Ladies ever to hold that position.

Did You Know…?

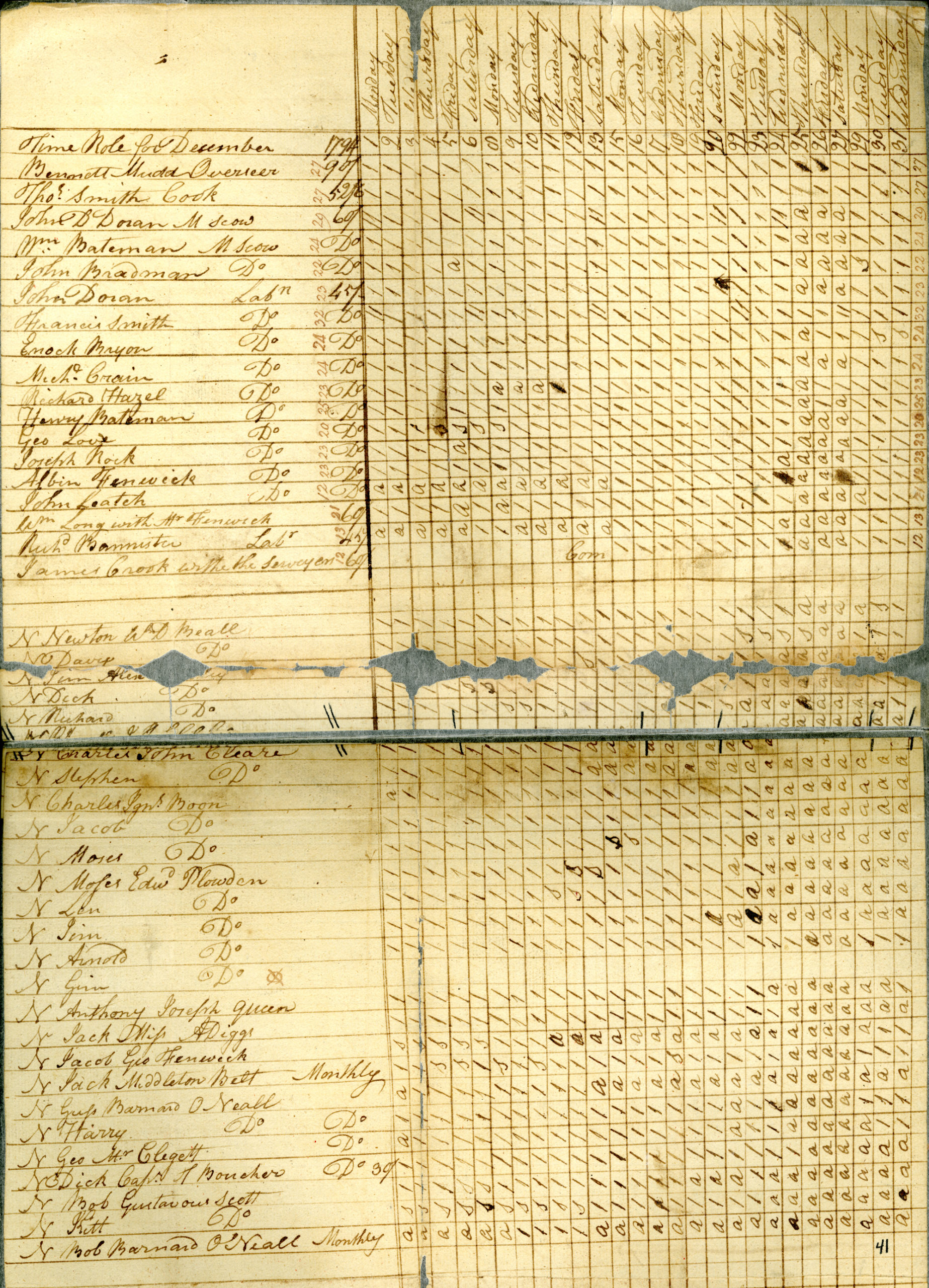

President’s house laborers payroll

When the land had been cleared in Washington, D.C., for construction of the White House and the U.S. Capitol in 1795, the Board of Commissioners in charge of the project used enslaved African Americans to move supplies, do carpentry and lay stones and bricks. The National Archives holds many records, including vouchers, promissory notes and wage rolls, that document the work enslaved persons did on these two buildings.

See the Records