We The People Have Some Changes

Last week ahead of Constitution Day, the National Archives hosted its annual naturalization ceremony in the Rotunda. Twenty-five new citizens from twenty-one different countries took their citizenship oaths in front of our – now their – Founding Documents. The event reminds us that our government isn’t just what’s written in the charters – it’s how citizens participate.

Participating in democracy is written in our national DNA. The brilliance of the Founders was their vision and understanding that the country would grow, evolve, and change, and so too should the Constitution. Article V is what makes the U.S. Constitution dynamic and enduring.

The ink was barely dry when the first ten amendments were introduced. In the 235 years since its passage, more than 11,000 amendments have been proposed, yet only twenty-seven have made it to the finish line and been ratified.

In celebration of Constitution Day, we’re taking a look at a handful of both quirky and traditional amendments and their stories.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Taxation without Representation

No taxation without representation

National Archives Identifier: 6011646

The District of Columbia, the seat of the nation’s federal government, is home to more than 700,000 people, which is more than the states of Wyoming or Vermont. Yet the residents of the district have no representatives in either the House of Representatives or the Senate. Per person, they also pay more in federal taxes than any other state – thus the slogan on DC license plates “End Taxation without Representation,” a direct reference to the taxes levied on the colonies by the British government before the U.S. Revolutionary War.

The twenty-third amendment, approved by Congress in 1960 and ratified by the states in 1961, gave residents of the district the right to vote in presidential elections. In 1970, the District of Columbia Delegate Act gave them the right to elect a delegate to the House of Representatives. Delegates can sit in the House, vote in committee, and offer amendments to bills, but they can’t vote on legislation. In 1973, the Home Rule Act allowed D.C. residents to elect a mayor and a thirteen-member city council. However, only sixteen states ratified the 1979 District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment, which would have given the district the same status as a state, with the same representation in the House of Representatives and the Senate.

DC Statehood resolution

Source: NARA’s Prologue Magazine

Currently, Congress can nullify any legislation passed by the local government of the district and can review the budget, which is an extraordinary exercise of authority by the federal government over any local government.

On January 4, 2021, Eleanor Holmes Norton, the District representative, introduced the Washington, D.C., Admission Act in the House of Representatives. It passed the House on April 22, 2021, and is now awaiting action in the Senate. If it passes there and the President signs it into law, it will grant Washington, D.C., admission into the United States as a state, with all the rights and privileges pertaining thereto.

No Compromise

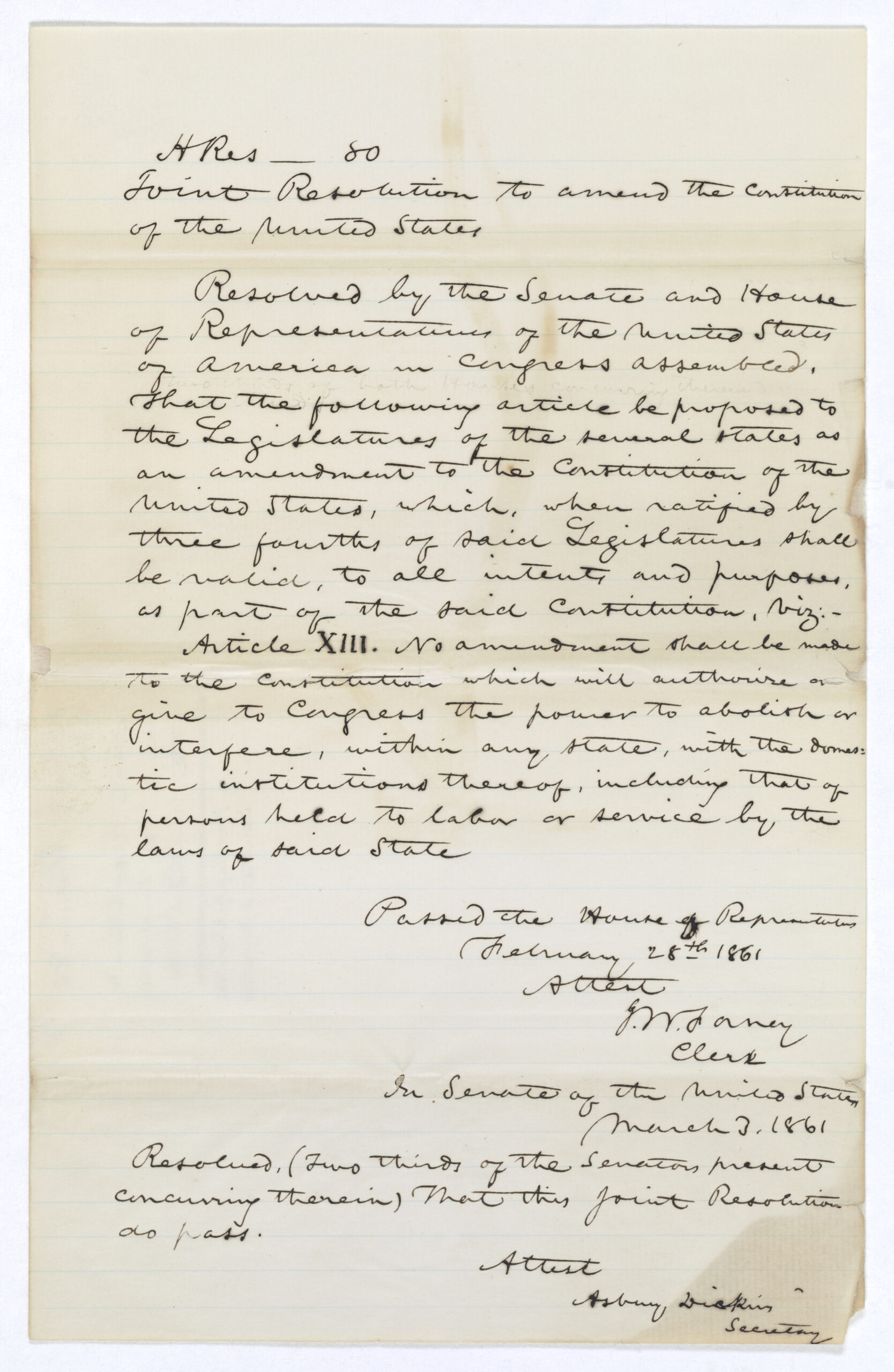

Joint Resolution 80 to prohibit Congress from outlawing slavery

National Archives Identifier: 24824293

House Joint Resolution 80 could be thought of as a last-ditch attempt to preserve the union. Just before the Civil War began, Representative Thomas Corwin, a Republican from Ohio, introduced an amendment that would have prevented Congress from abolishing slavery. The resolution passed the House on February 28, 1861, and the Senate on March 3, but only five states had ratified it when Confederate troops fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on April 12. At that point, all hope of preventing slavery from being abolished by constitutional amendment evaporated. After the war ended, the thirteenth amendment, which abolished slavery in the United States forever, was passed by Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified on December 6 of that year.

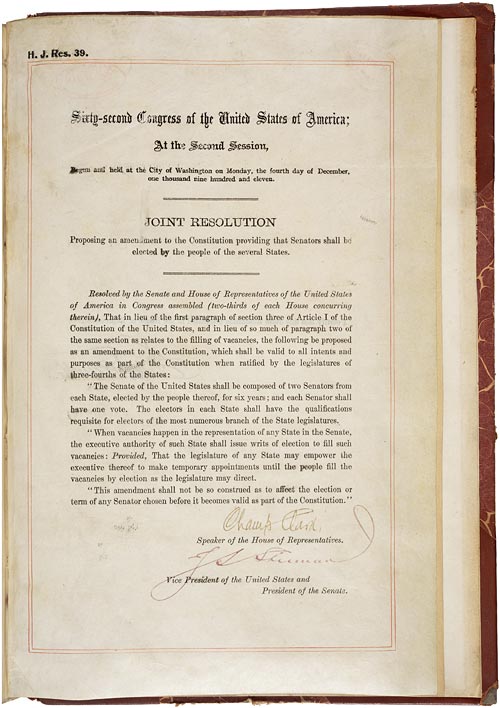

Abolish the Senate

17th amendment providing for the direct election of Senators

NARA’s Milestone Documents

Victor Luitpold Berger was a real charmer. Elected in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, he was the first socialist ever elected to the House of Representatives, and he promptly set about stirring things up as soon as he arrived in Washington, D.C.

At various points in his first (brief) political career, Berger wanted to eliminate the President’s veto power, nationalize the wireless radio system (this was immediately after the Titanic sank in 1912), and create a national old-age pension system.

But he also introduced a bill on April 27, 1911, that would have amended the Constitution to abolish the Senate. The preamble gave the smaller chamber of the legislature no quarter: “Whereas the Senate in particular has become an obstructive and useless body, a menace to the liberties of the people, and an obstacle to social growth; a body, many of the Members of which are representatives neither of a State nor of its people, but solely of certain predatory combinations, and a body which, by reason of the corruption often attending the election of its Members, has furnished the gravest public scandals in the history of the nation. . . .”

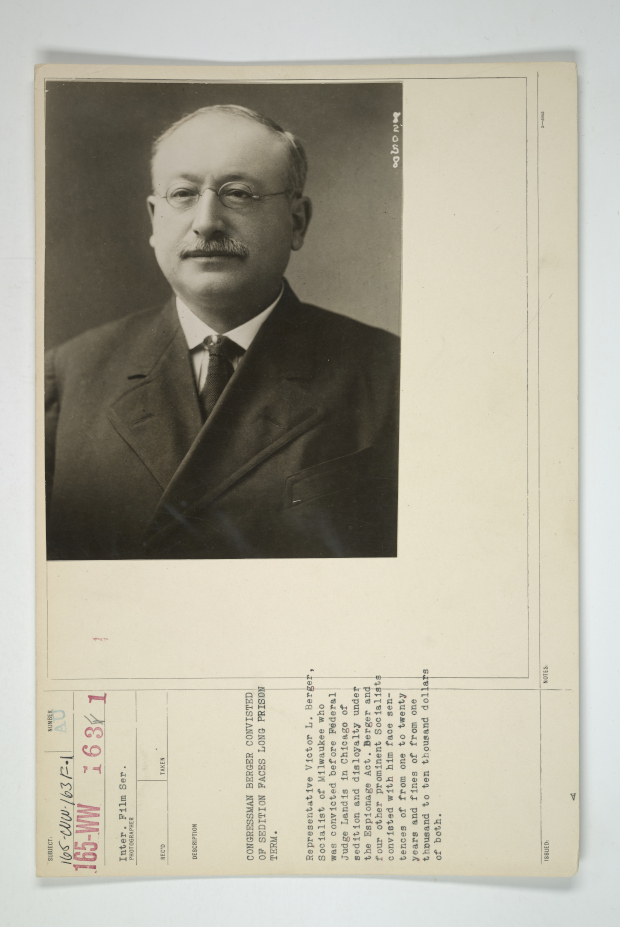

Berger’s conviction of espionage

National Archives Identifier: 31479984

Berger’s amendment died in committee, and his constituents in Wisconsin promptly sent him packing and declined to reelect him when he ran again in 1912, 1914, or 1916. When World War I began, Berger, who was born to Jewish parents in what is now Romania, opposed U.S. involvement in the war, which made the government suspicious of his motives. In February 1918, he and four other socialists were indicted under the Espionage Act. Berger was convicted and sentenced to twenty years in prison on February 20, 1919. However, he appealed his sentence all the way to the Supreme Court, which overturned his conviction.

In the meantime, he ran and was elected to the House of Representatives in 1918, but he was disqualified because he was under indictment. He was elected again in a special election in 1920, but the House refused to seat him. He was defeated in the 1920 election by Republican William H. Stafford, but he regained his seat in 1922, 1924, and 1926. Back in the House, he worked on unemployment insurance, public housing, the recognition of the Soviet Union, and, again, an old-age pension. In 1928, Stafford defeated Berger, and he went home to Milwaukee, where he went back to work as a newspaper editor. He was hit by a streetcar on July 16, 1929, and died on August 7.

Hold Your Fire

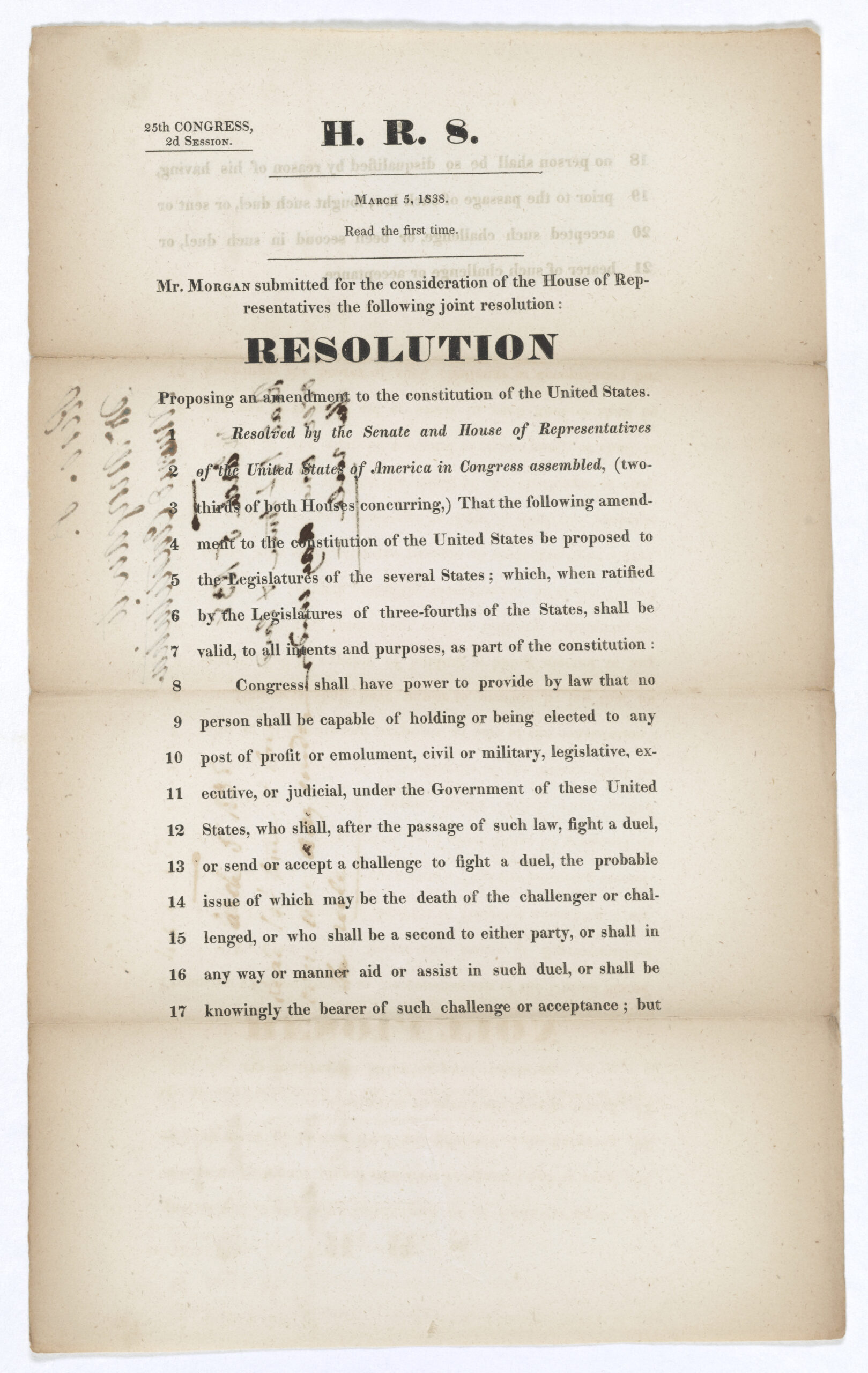

Proposed amendment

to ban dueling

National Archives Identifier: 25466015

Quite possibly the best-known duel in American history took place on July 11, 1804, when Vice President Aaron Burr mortally wounded Alexander Hamilton on the dueling grounds near Weehawken, New Jersey. Shot in the stomach, Hamilton died the next day in New York. Burr returned to Washington, D.C., where he was charged with murder but never tried. The duel ended Burr’s political career, however, and Burr went on to plot a revolt against the United States government. He was tried and acquitted of treason in 1807.

On March 5, 1838, after several more high-profile duels involving members of Congress, Congressman William Stephen Morgan of Virginia introduced House Resolution 8, which would have amended the Constitution to prohibit anyone holding federal public office from dueling and barring anyone who took part in a duel after it was passed from holding office. Morgan wrote his resolution after Representative Jonathan Cilley of Maine was killed in a duel with William Graves of Kentucky on February 24, 1838. Morgan’s resolution was considered, but not passed.

It’s Crowded in Here

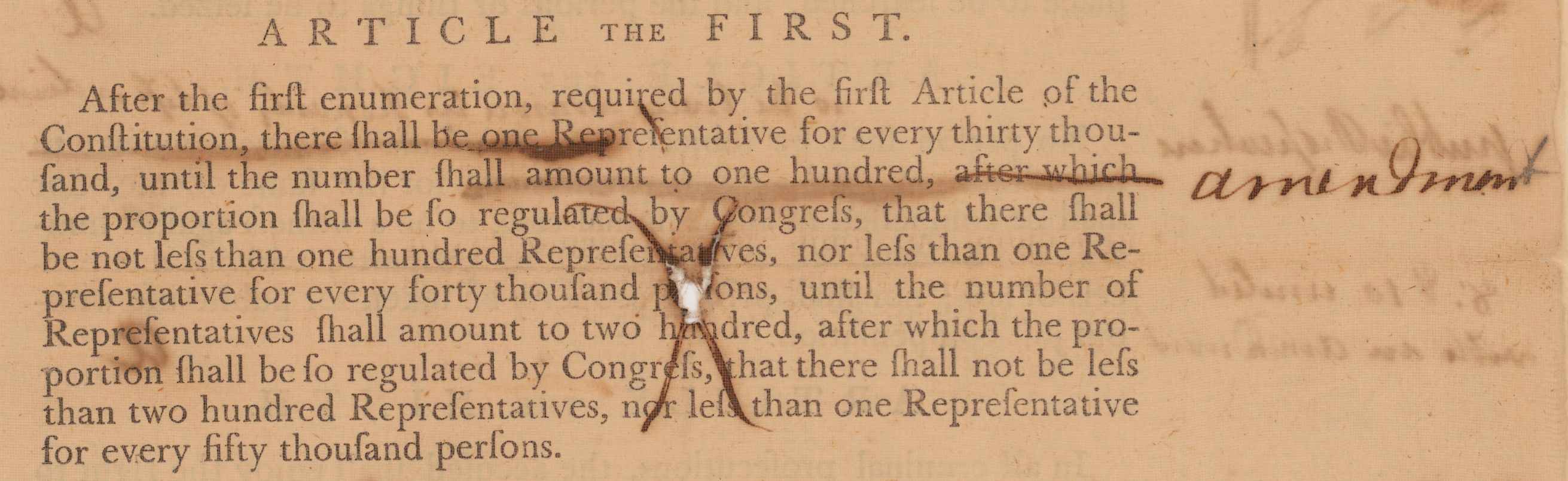

Article the First

National Archives Identifier: 3535588

When the very first Congress sent the original twelve amendments out to the states for their consideration, the first one had to do with how representation in Congress would be determined going forward. The text of the first amendment read, “After the first enumeration required by the first article of the Constitution, there shall be one Representative for every thirty thousand, until the number shall amount to one hundred, after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall be not less than one hundred Representatives, nor less than one Representative for every forty thousand persons, until the number of Representatives shall amount to two hundred; after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall not be less than two hundred Representatives, nor more than one Representative for every fifty thousand persons.”

If that amendment had been ratified, instead of 435 members of the House of Representatives, we would now have more than 10,000, and, to misquote Jo March in Little Women, “the [H]ouse wouldn’t hold them, and master and missis would have to camp in the garden.”

The number of representatives was set at 433 in 1911, when Congress decided that was the most that could be accommodated without any state losing any representation. At the time, Arizona and New Mexico were also about to become states, so Congress allowed for each one to have a single representative, finalizing the number of seats at 435. The Reapportionment Act of 1929 reaffirmed that number.

| The Senate’s first round of edits to the original Bill of Rights National Archives Identifier: 3535588 |

||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|