The Origin Story

Can you imagine a time without the National Archives?

Today, the Archives’ ornate building is a must-see on the National Mall. The iconic documents it houses – the Charters of Freedom – are perhaps the most famous in the world; and in 2004, the Archives became the main character in the now cult-classic film National Treasure.

But as far as government agencies are concerned, the National Archives and Records Administration is a middle child, not existing as an official agency until 1934. From the revolution to the creation of the agency, government records were stored in every imaginable place, and despite many debates, there was no consensus on the need for a national archives.

Because the Archives also holds records about itself, we’re taking a look at how it finally came to be. Join us as we celebrate American Archives Month!

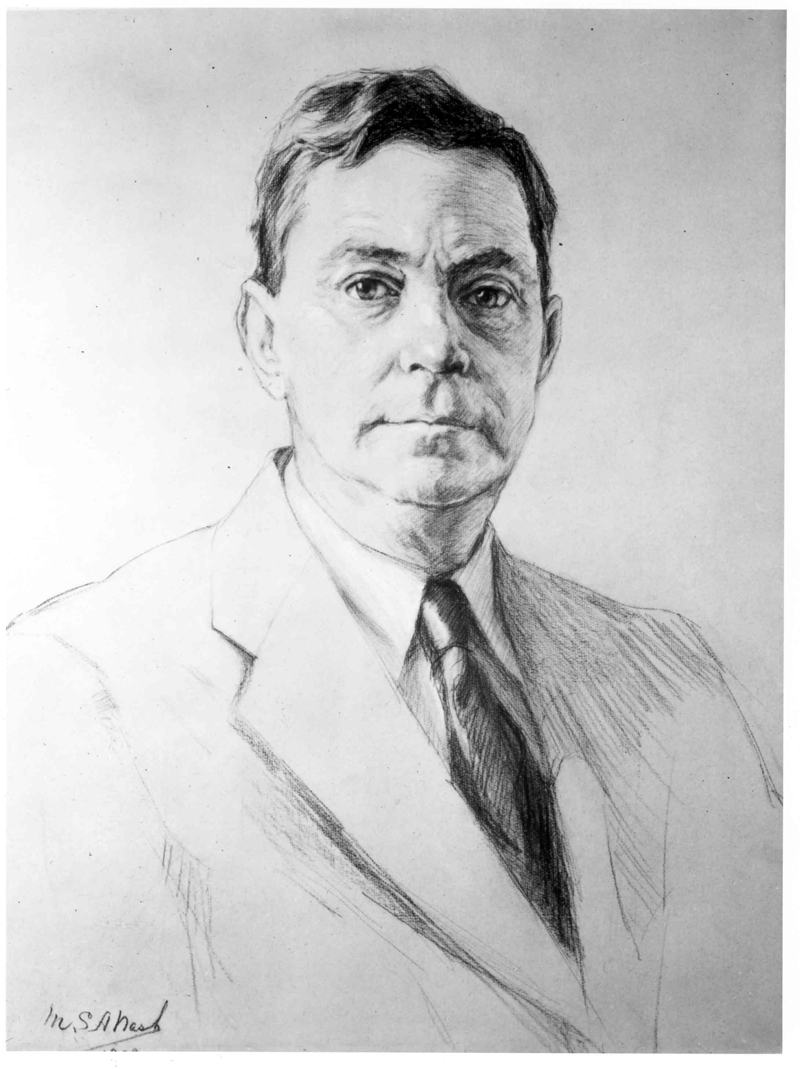

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Scattered

Taking the long view – which is to say, our view, the view of nearly 250 years – it does seem like it took far too long for the nation to realize we needed a permanent, fireproof, bombproof, pest-proof, temperature- and humidity-controlled building in which to store the nation’s historical records and a federal agency to look after them. But it is always wise to be a little less judgmental toward those who lived before us –it’s impossible to know exactly what they knew at the time or to take the exact temperature of the societal oceans in which they swam. In her article “A Temple to Clio: The National Archives Building,” Virginia C. Purdy, a historian and archivist who worked at NARA for 20 years, records that “At the ceremonial laying of the cornerstone in 1933, Secretary of the Treasury Ogden L. Mills saw the previous lack of concern for government records as ‘unmistakable evidence of the youth of our country and of how intent we have been on the future rather than the past.’”

Documents in the White House garage

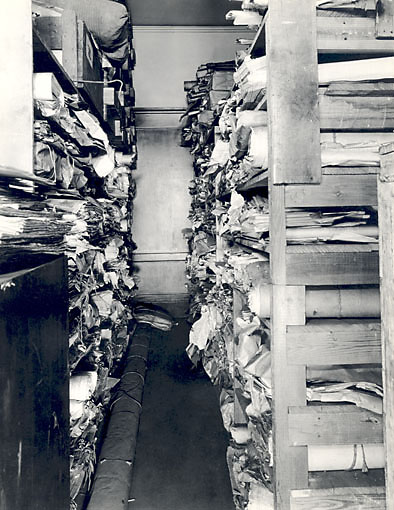

Before the National Archives and Records Administration of the United States became a reality, the nation’s historical records, including the key founding documents that we now call the Charters of Freedom, were preserved by different agencies and in varying degrees of safety. The most obvious threat was fire. The War Department Building burned down completely in 1800, along with all its historical documents. In 1801, the Treasury Building burned nearly to the ground, and all the documents in it were lost. The government then added the Latrobe Wing, which was fireproof, to the Treasury Building. The British burned that building again in 1814, during the War of 1812, but the Latrobe Wing survived. Then in 1833, Richard H. White set fire to the newly built Treasury Building to destroy incriminating pension records. Again, many documents were destroyed.

On September 26, 1877, the top floor of the Patent Office Building caught fire, destroying more than 80,000 models and 600,000 copy drawings. Then on January 21, 1921, a truly terrible conflagration occurred when the Department of Commerce Building caught fire. When the blaze was finally extinguished and archivists were allowed back into the building the next day, they waded through water up to their ankles and stepped on broken glass and other debris. Almost all of the records of the 1890 population census were lost, about a quarter of them to the fire itself and half to water and smoke damage.

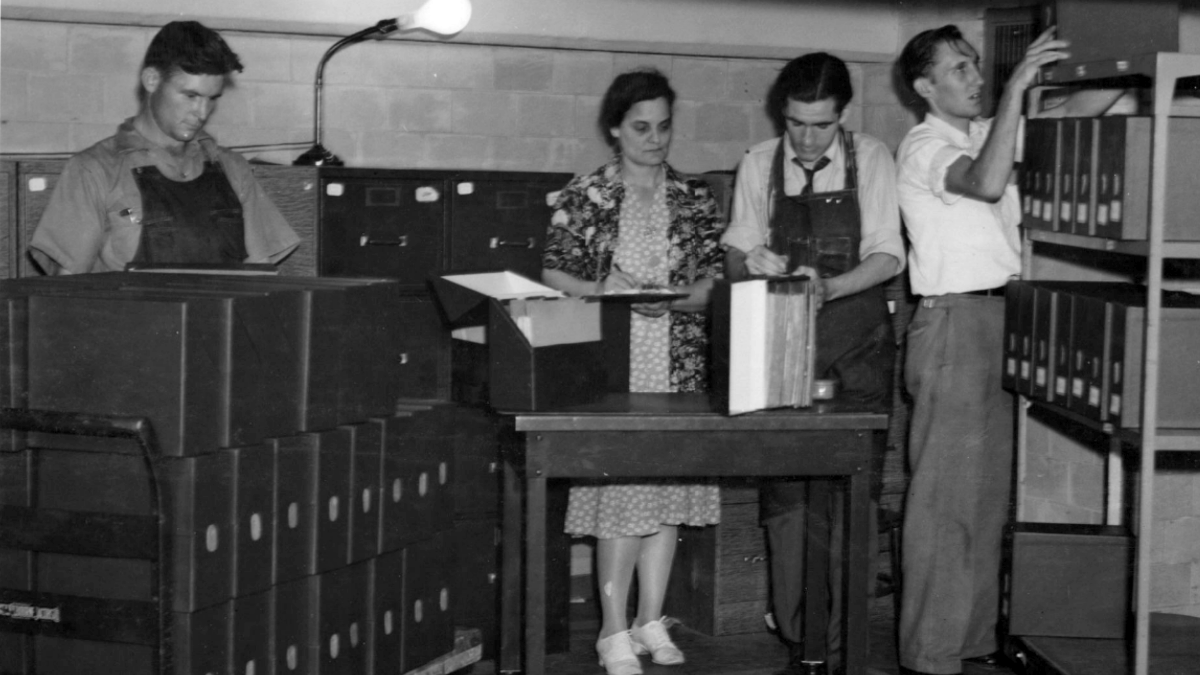

Storage at Office of Indian Affairs (1935)

Besides fire, important documents often suffered the effects of heat, light and humidity. For instance, while the Declaration of Independence was on display for 35 years in the Patent Office Building (now the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution) in Washington, D.C., it was hung in a large hall with south-facing windows and a skylight. Consequently, the ink on the document faded to a light brown.

In 1876, the Declaration was moved to the State Department and put on display in the library. By then, everyone agreed that such documents should only be displayed in indirect light. In 1921, both the Constitution and the Declaration were moved to the Library of Congress, where they were displayed in a case with double panes of glass with yellow gelatin filters to block damaging light. All seemed well until the 1940s, when workers discovered bugs in the case that held the Constitution. Furthermore, it was impossible to control the humidity in the cases that held both the Constitution and the Declaration, which was causing the parchment of both documents to expand and contract.

Then after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, both the founding documents and other irreplaceable materials were shipped from the Library of Congress via train to Fort Knox for the duration of the war. Once they were returned to Washington, a little inter-agency bickering occurred for a bit about where they should reside. But in 1951, the new Archivist and the new Librarian of Congress worked out a deal, and the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights all took up permanent residence in the National Archives building.

All along, some agencies had objected to the idea of depositing all their documents in one place, arguing that it was a security threat. (Doubtless, some also worried about losing control of their records.) In the end, however, they turned their documents over to the National Archives for cleaning, sorting and storage in the new building.

The Charters of Freedom are now enclosed in argon-filled aluminum and titanium cases with electronic equipment that continuously monitors the conditions inside them. They and other invaluable materials in the National Archives regularly undergo evaluation and treatment by conservators. The key guideline by which conservators work is that any treatment they apply must be completely reversible. Conservators understand, as we all should, that we will continue to learn as time advances and that treatments will continuously evolve. Thus, any actions we take in preserving the past for future generations should not endanger the legacy we wish to leave for them.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

Blueprints

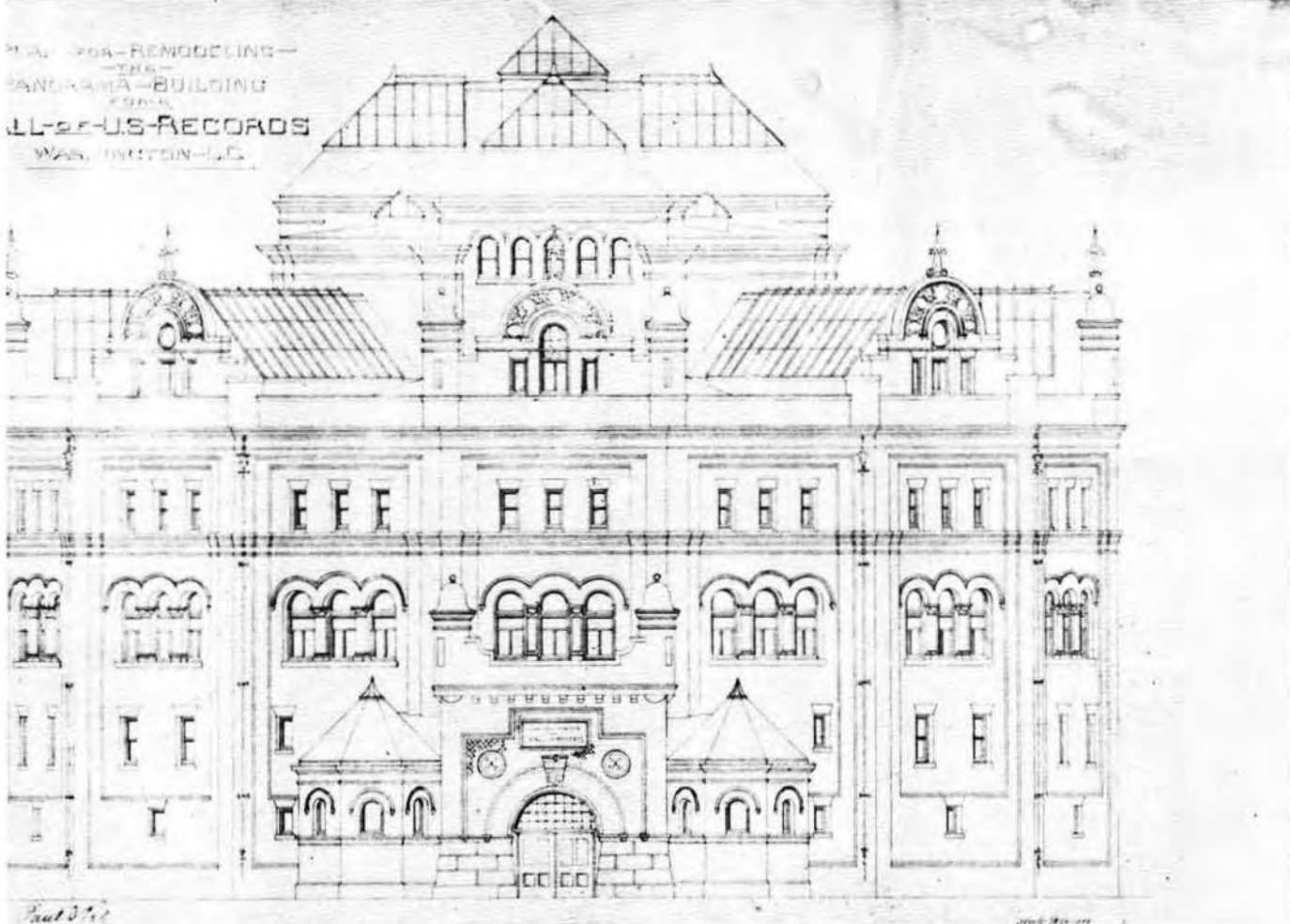

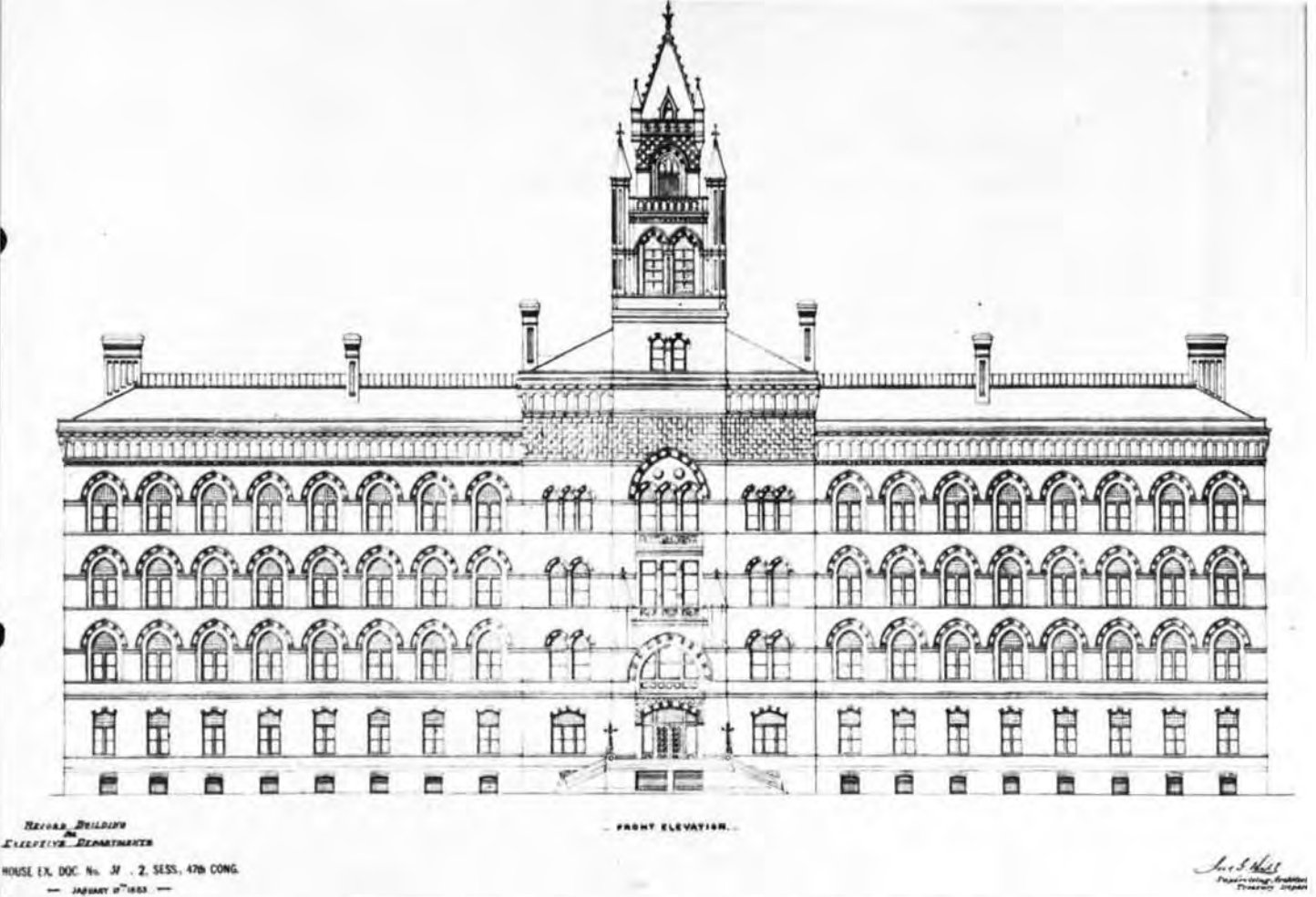

Original proposal for Hall of Records

From the beginning of the republic, citizens have spoken out in favor of a permanent, fireproof building that would house and protect the nation’s historical records for the benefit of the American people. One of the first was Congressman Josiah Quincy, a Federalist member of the House of Representatives from Massachusetts, who voiced his opinion in 1810, just a few years after both the War Department and the Treasury Department had burned down in Washington, destroying multitudes of important documents. His recommendation went nowhere.

After the Patent Office Building fire in 1877, Montgomery C. Meigs, who was the quartermaster general, drew up plans for a fireproof hall of records. His recommendation went nowhere.

Enter J. Franklin Jameson, who finally carried the ball over the goal line. At the end of the 19th century, members of the American Historical Association, led by President Jameson, were urging the federal government to create a permanent national archives. Jameson published a study of European archives, and he and other AHA members submitted a plan for a hall of records to Congress in 1898. The federal legislature did authorize an archives in 1903, but that recommendation went nowhere.

But Jameson was relentless. He talked to President William Howard Taft about the idea in 1907, and Taft ordered all agencies to survey their record spaces and recordkeeping. Jameson sat on a Committee on Documentary Historical Publications that recommended that an archives be built. He kept talking to President Taft, and the President kept talking to Congress, telling the legislature on December 3, 1912, that “A hall of archives is also badly needed, but nothing has been done toward its construction, although the land for it has long been bought and paid for.” Congress set aside $5,000 for plans for an archives building, which Jameson immediately drew up, but again, the recommendation went nowhere.

Original proposal for Hall of Records

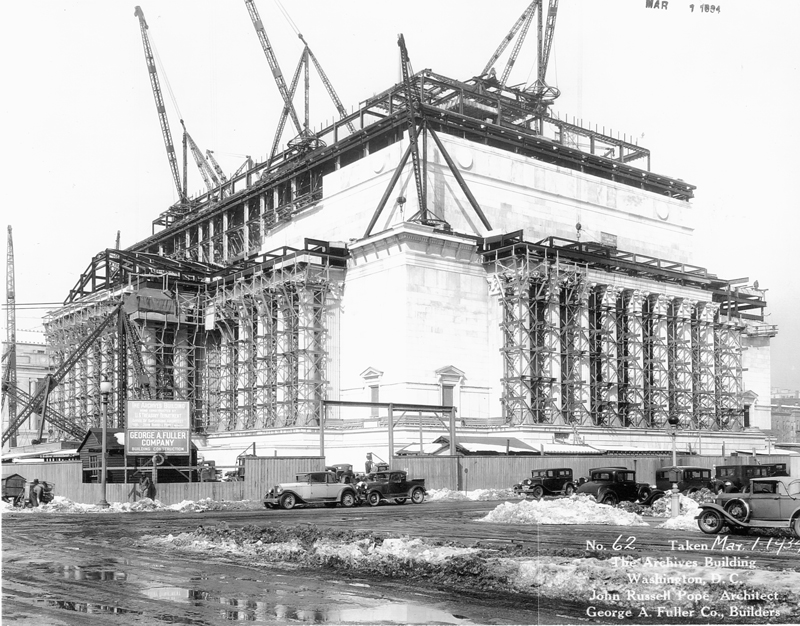

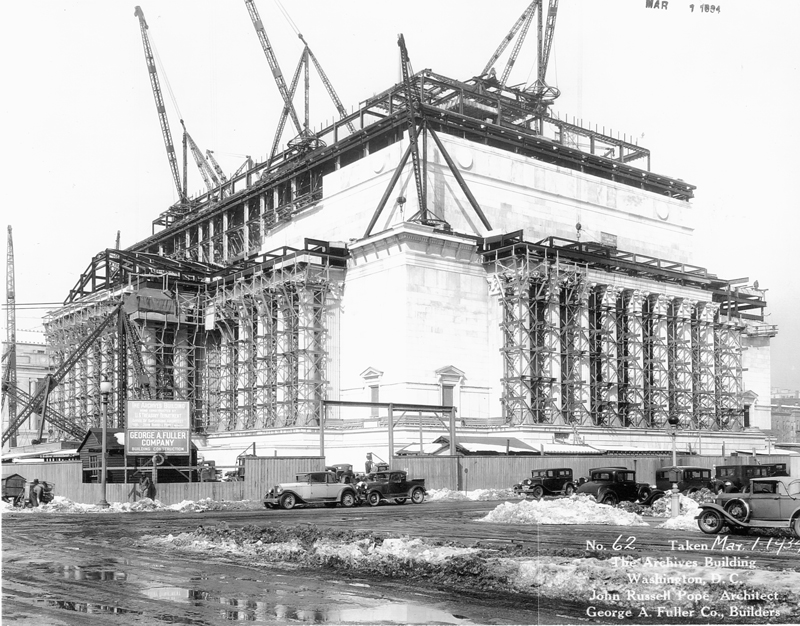

Finally, after the disastrous fire at the Department of Commerce in 1921, which destroyed 75% of the records of the 1890 population census, Congress passed the Public Buildings Act of 1926. Among other actions, the act appropriated funds for the National Archives building. Construction began in 1933 and was completed in 1937, just before J. Franklin Jameson died.

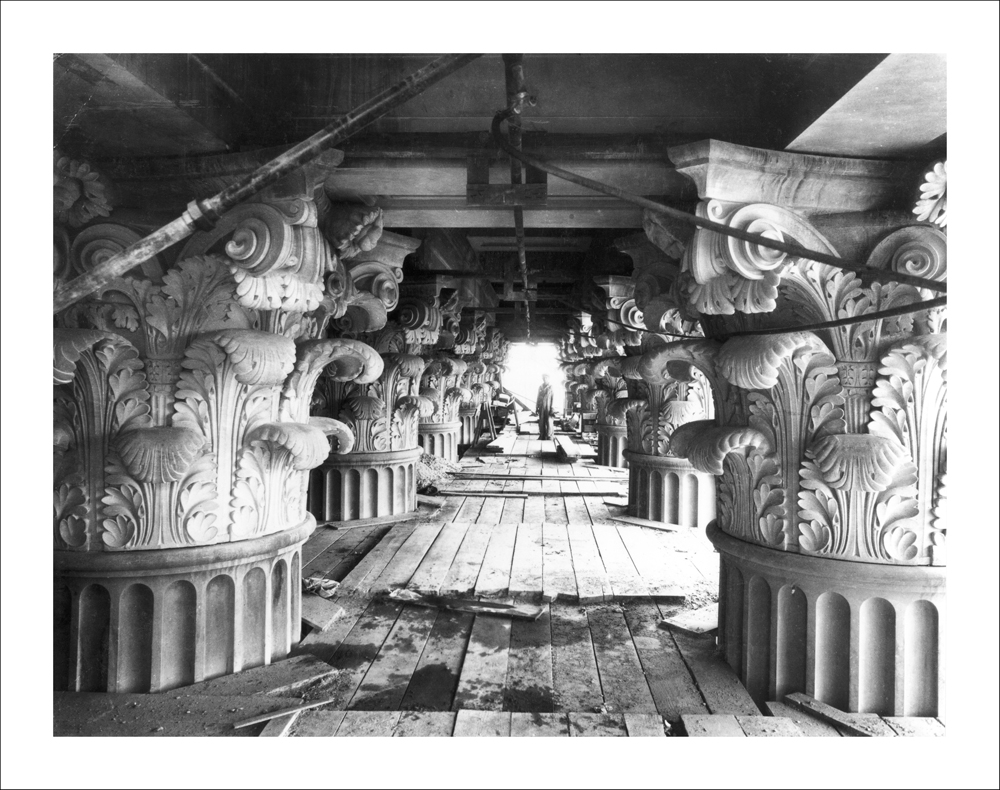

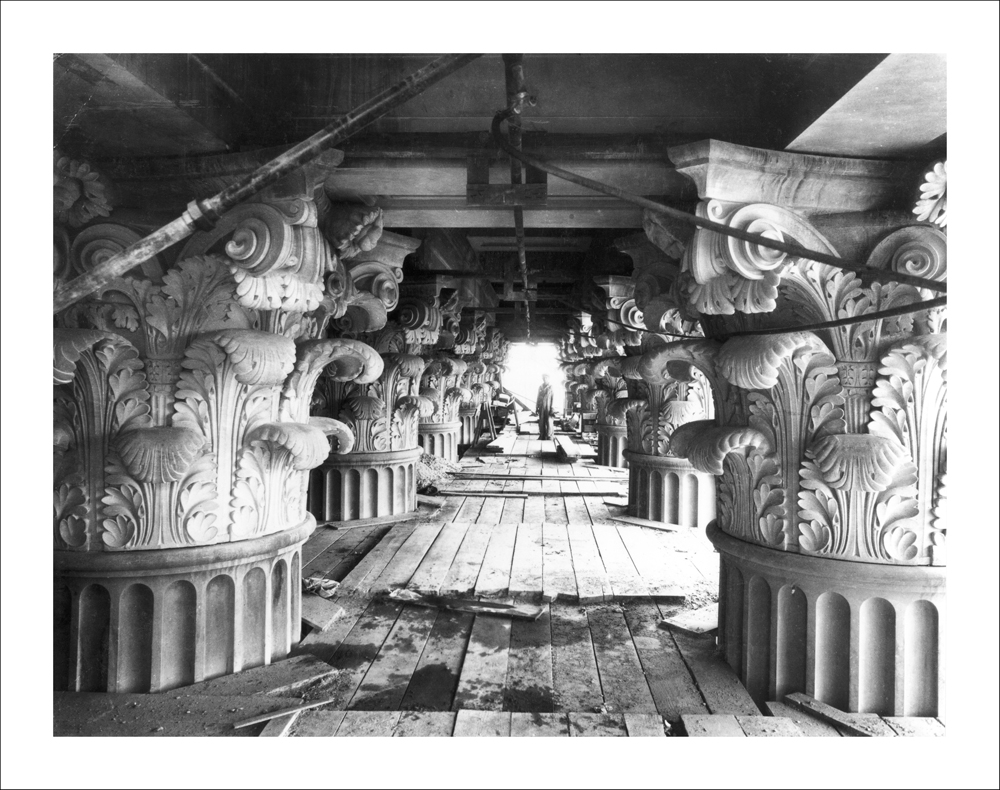

The selected architect of the building was John Russell Pope, and he and his team did not have an easy task ahead of them. Although they visited other archival facilities abroad, many of them were ancient castles, manor houses or converted government buildings that had all been built for a prior purpose. The National Archives in Washington, D.C., would be the first building in the world to be specifically built as an archival facility for paper documents, so they were truly starting from scratch.

Pope’s vision for the design of the building was also called into question. His peers jokingly called him “The Last of the Romans.” In the 1930s, when function dictated form, his neoclassical style was thought outdated and unnecessarily ostentatious. But Pope persisted with his vision, resulting in the iconic landmark the Archives building is today.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

The Archivist and the President

President Herbert Hoover presided over the laying of the cornerstone of the National Archives on February 20, 1933, and then he left office two weeks later. Franklin Delano Roosevelt became president at the worst point of the Great Depression, when millions of Americans had lost their jobs and homes and were looking to him for help. Roosevelt wasted no time in stepping up, creating programs and agencies designed to put his people back to work and get the economy moving again.

But FDR had also inherited the rising National Archives building, and perhaps it isn’t surprising that while the building was going up, there was no agency in place to inhabit it. The president promptly moved to get legislation passed to create the National Archives, establish the position of National Archivist, hire a staff and gather and move the records of the various government agencies to their permanent home in the National Archives building.

FDR remained involved in the management of the National Archives for the rest of his life. When it became clear early on that the need for storage space in the building had been drastically underestimated, he stepped in to help solve the problem. The courtyard that had been part of the early design was immediately filled in to make room for 800,000 cubic square feet of additional documents. He made suggestions about staffing and recommended that films be added to the materials that were preserved in the archives.

And he began to collect his own private papers, books and memorabilia at his estate in Hyde Park, which he stored in a fireproof building that he then gave to the government as the first presidential library, a precedent that continues to this day.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

Miles and Miles

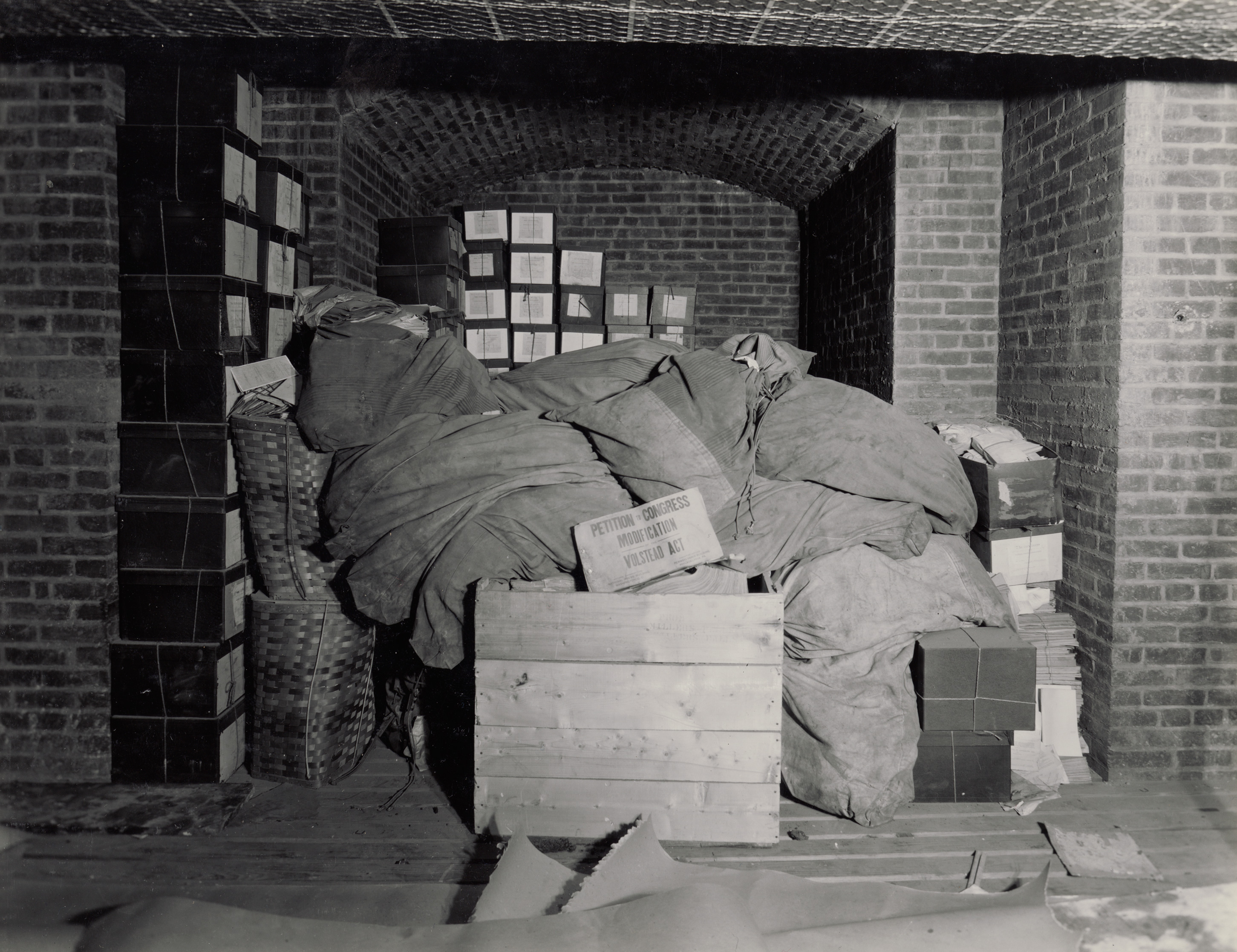

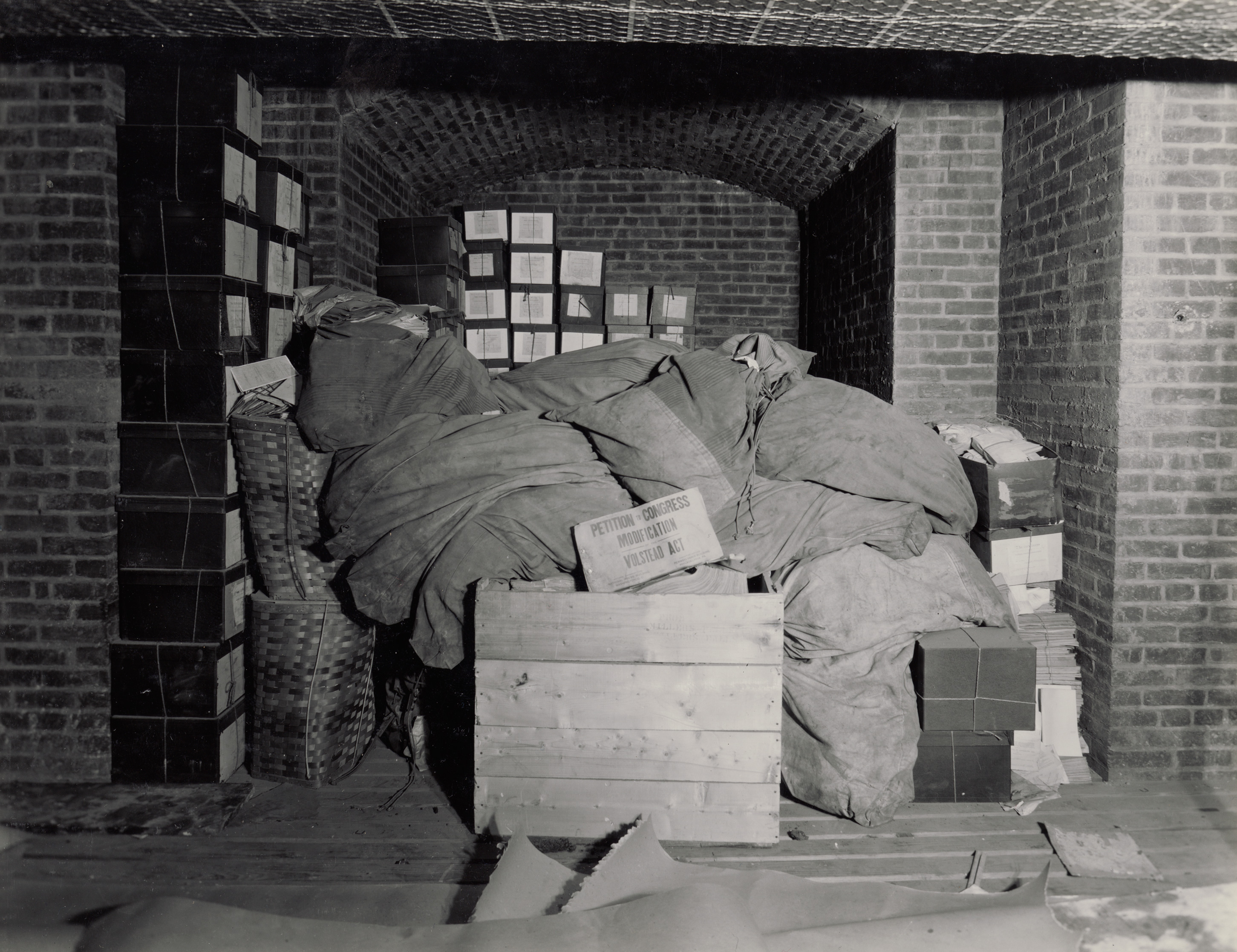

Red tape collection

After the Civil War, the size of the U.S. government expanded dramatically, making the need for efficient storage even greater. But an even greater challenge was ease of access. When veterans of the Civil War wanted access to their service records to file pensions, they were required to travel to the War Department in Washington, D.C., where documents were bundled together with red ribbon. Accessing these records was difficult, but when they were found, the ribbon was cut open revealing the documents inside. This saying has stayed with us, becoming the colloquialism “cut through the red tape.”

The Archives has so much of this red tape left over (miles of it!) that you can still buy it. Local D.C. artists make it into paperweights, jewelry, cufflinks…you name it!

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

Plan Your Trip

Plan your trip here!

During our busy season, the National Archives can receive up to 5,000 visitors per day. We’re also a popular destination for school field trips, so it’s not surprising that one-third of all visitors to the Archives are eighth-graders.