The National Archives Has the Receipts

Nowadays, when the cashier (or more often, self-checkout) rings up your purchases and you tap your card on the chip reader, the transaction appears on your bank account before you even get home. How many of us bother to take the paper receipts? Maybe we should, but it often just seems like one more piece of paper to stuff in our pocket or purse.

But not that long ago, the paper receipt was an important record of the transaction, proof of the funds exchanged and of the resulting zero balance. Some of the most important moments of our history are recorded in receipts, and they’re here at the National Archives. Join us for an audit…

In this issue

History Snack

Payment Declined

December 1794 payroll for enslaved people at the President’s House

Source: NARA’s Press Releases 2009

Enslaved African Americans were largely responsible for building both the President’s House and the Capitol. The National Archives has in its holdings promissory notes, payment vouchers, and payroll records for enslaved carpenters, joiners, laborers, and bricklayers who worked on both buildings between 1795 and 1800. The slaves’ owners received their wages upon signing the payroll record. In all, 122 people identified as “Negro hire” were listed as having worked on the Capitol and the President’s House.

Incidentally, the President’s House was the unofficial name for the combined residence and office until 1810, when it was rechristened the Executive Mansion. It did not become known as the White House until 1901, when President Theodore Roosevelt officially changed its name.

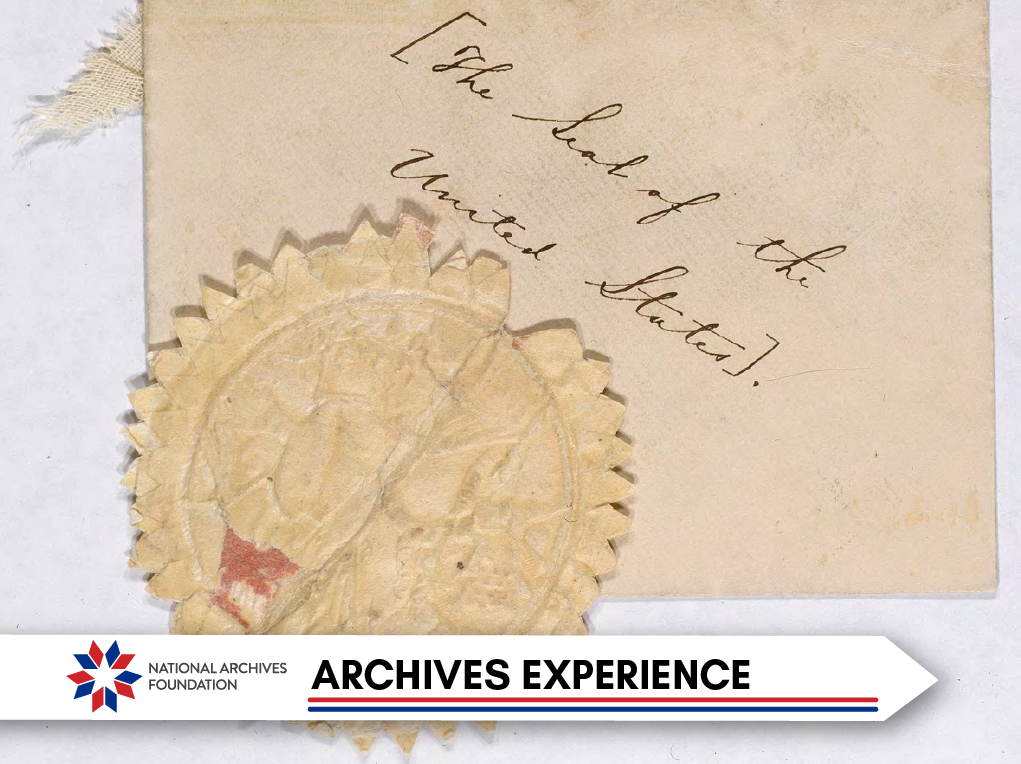

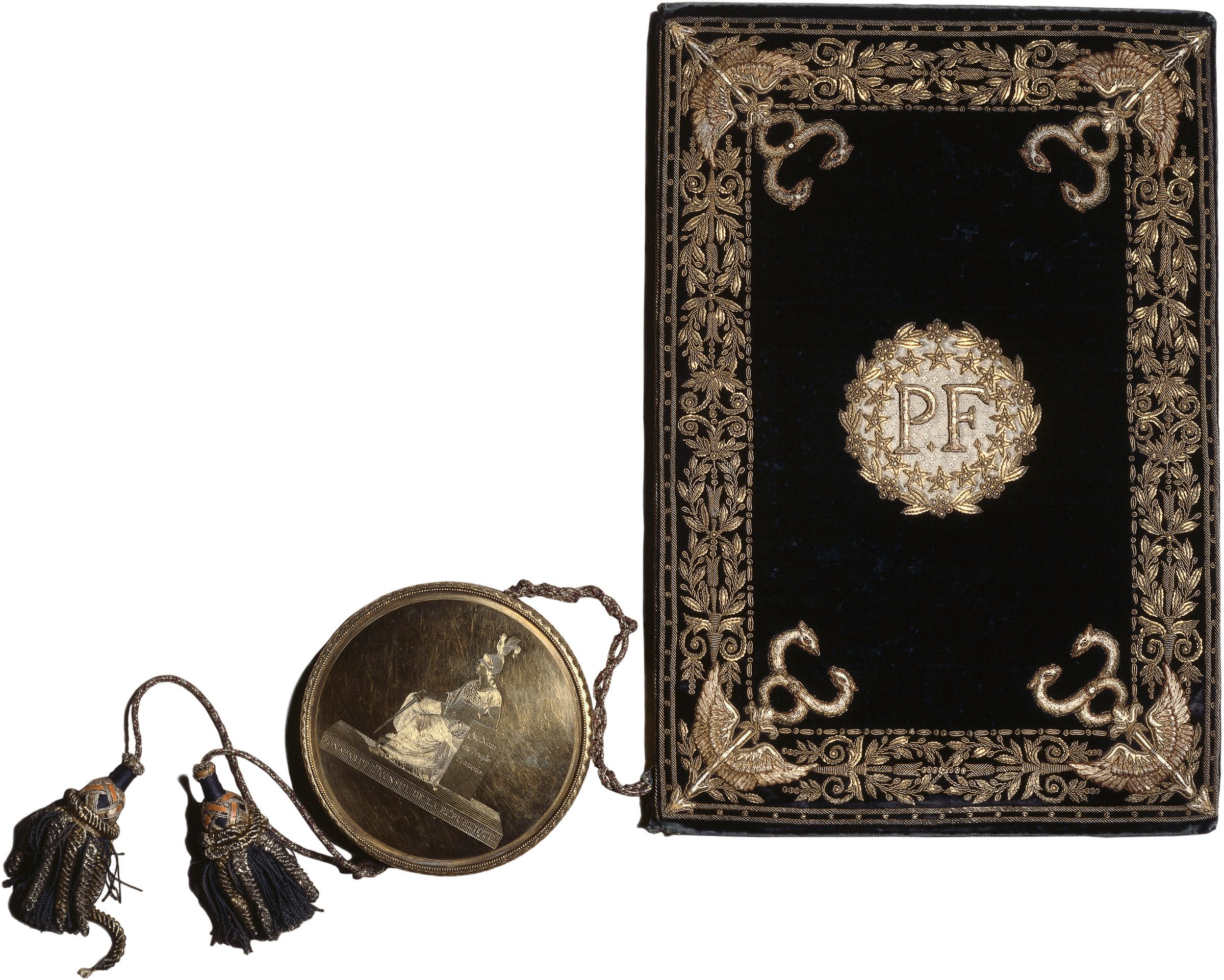

Credit Limit Exceeded

Treaty–agreement to pay France for the Louisiana Purchase

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

The major documents in NARA’s holdings about the Louisiana Purchase clearly demonstrate that the whole transaction was much more like a spur-of-the-moment elopement than a grand state wedding. The process took just over six months, which might seem like a long time until you take into account how long it took to get somewhere in that day and age, as well as how long it took to send a message from one side of the world to the other.

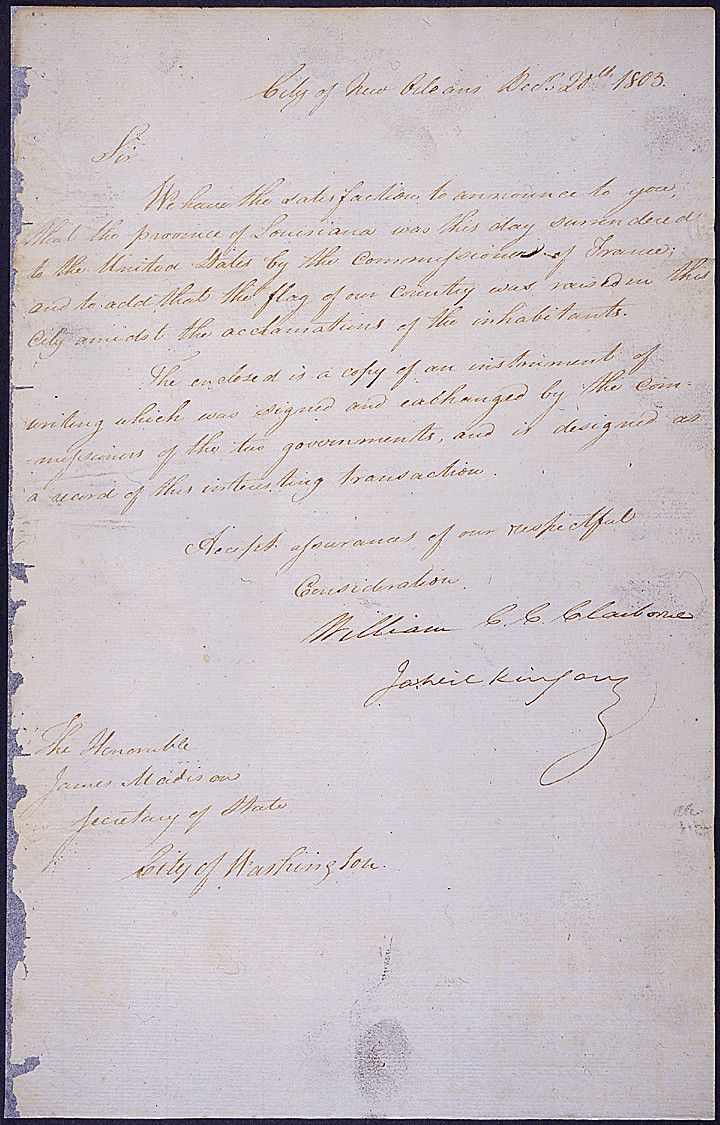

James Madison, Secretary of State, announces the surrender of Louisiana by the French

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

On March 8, 1803, James Monroe, the former governor of Virginia, having sold many of his household goods to pay for the trip, left the United States for Paris on President Thomas Jefferson’s commission, planning to offer Napoleon Bonaparte up to $10 million for the city of New Orleans and its environs and all or part of Florida. If Napoleon balked at that suggestion, Monroe was authorized to try to buy just New Orleans, or to at least gain access for the United States to the port and the Mississippi River.

But when Monroe arrived in Paris on April 11 and met with U.S. Minister Robert Frances Livingston the next day, he was stunned to learn that France was prepared to sell the entire Louisiana Territory, 530,000,000 acres that would include New Orleans, for $15 million dollars, roughly $403,708,407 in 2023 dollars.

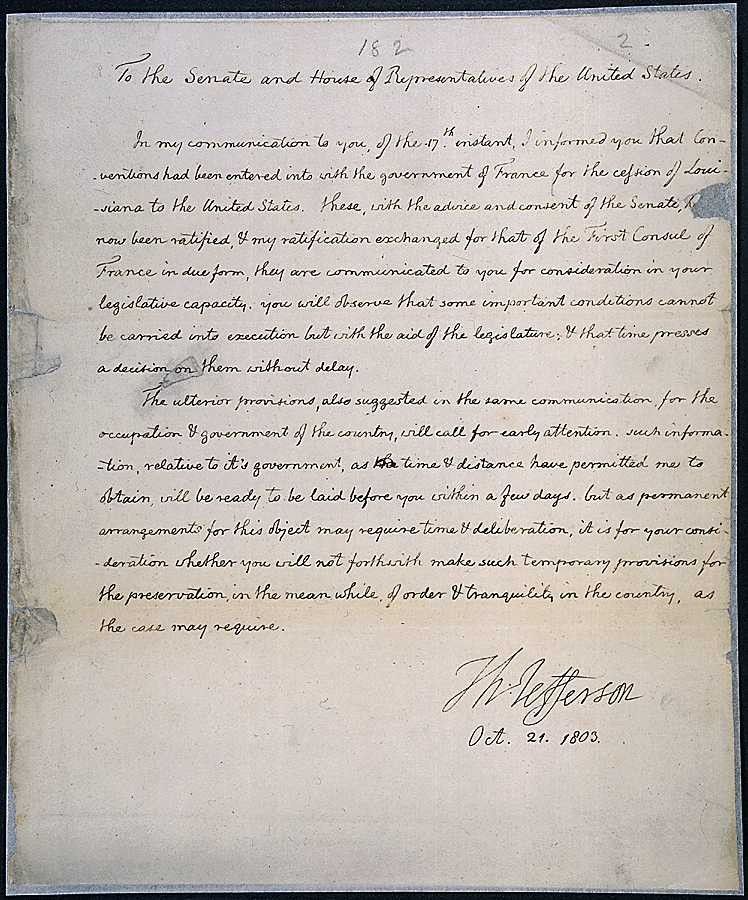

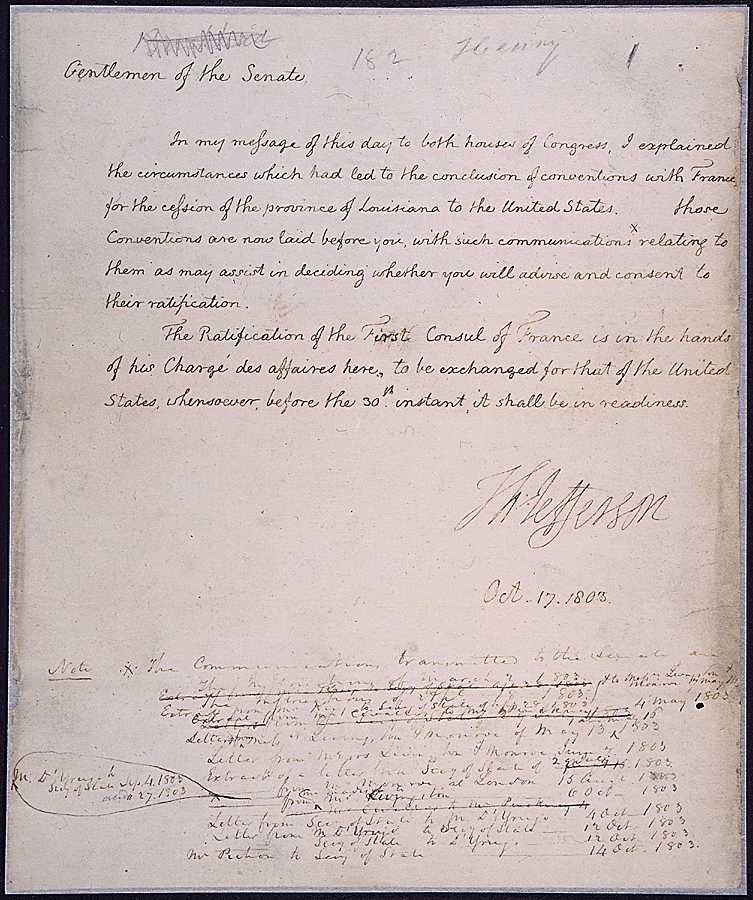

Jefferson’s message to Congress after the LA purchase was approved

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

At the time, Napoleon was gearing up for war with Great Britain, and he had decided that his Louisiana Territory was nothing but a drain on his attention and his resources. He had decided, and quite quickly, to sell the whole kit and kaboodle and to add the sale price to his war chest.

This is probably one of the most dramatic instances in history of asking forgiveness, not permission. With no time to waste, and no authority to spend more than $10 million, Livingston and Monroe nevertheless bought the Louisiana Territory for the United States for $15 million on April 30. The acquisition doubled the physical size of the United States and guaranteed it access to the entire Mississippi watershed, as well as extending the country’s boundary all the way to the Pacific Ocean. Official word of the deal reached Jefferson in time for him to announce it to the public on July 4, 1803. By a vote of 24 to 7, the Senate ratified the treaty on October 20, 1803.

Payment Approved

Thomas Jefferson asks Congress for LA approval

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

President Thomas Jefferson had already started making plans to send an exploratory expedition into the Louisiana Territory before the United States acquired it. In January 1803, he sent a secret message to Congress asking it to authorize funding to send an expedition up the Missouri River in search of the Northwest Passage and to establish friendly relations with the Indian tribes who inhabited those regions.

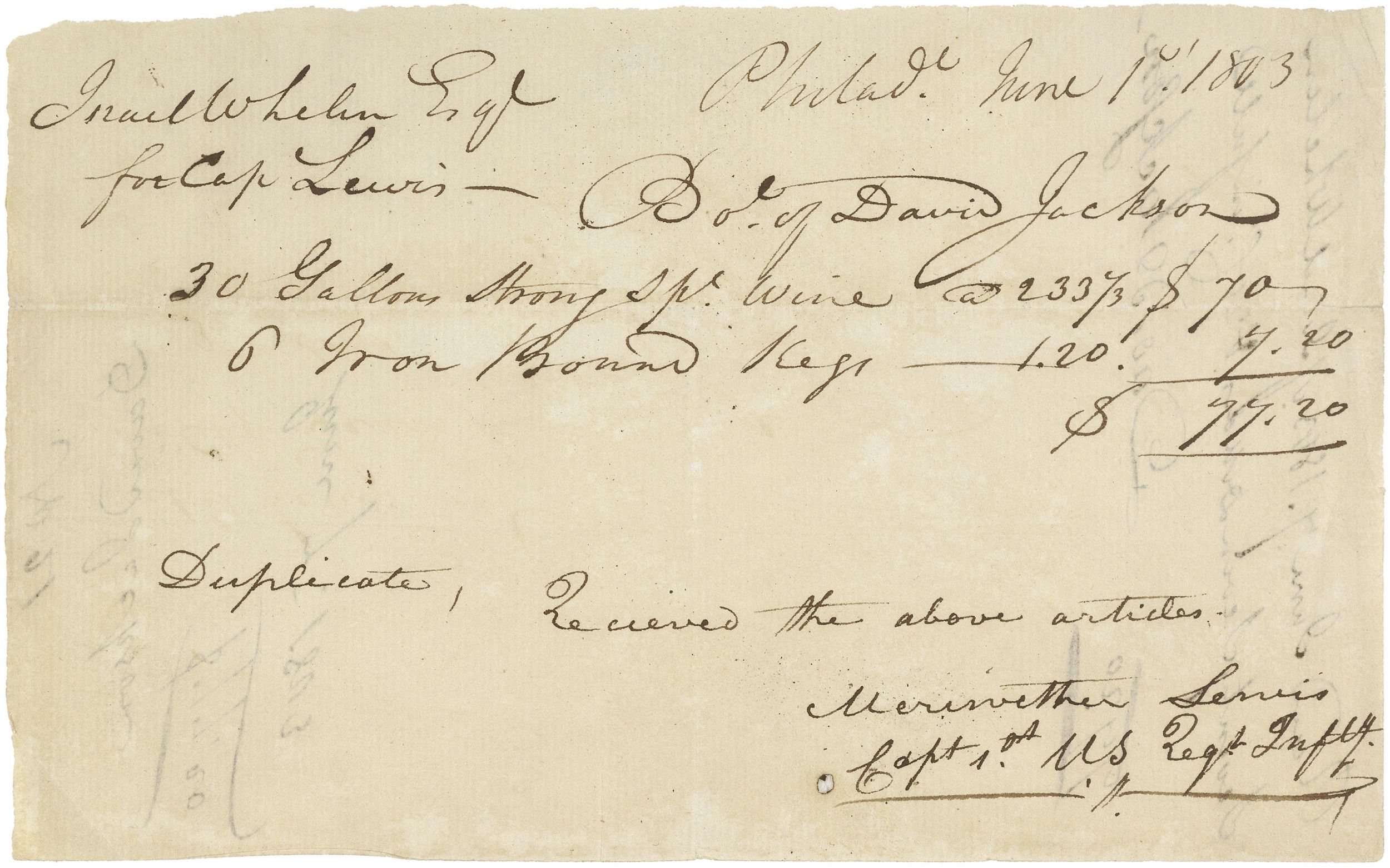

Receipt for wine and kegs for the trip to the West

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

Once the ink was dry on the Louisiana Purchase, Jefferson quickly appointed his personal secretary, Meriwether Lewis, to lead the expedition, and he sent him to Philadelphia to study botany, medicine, zoology, and celestial navigation.

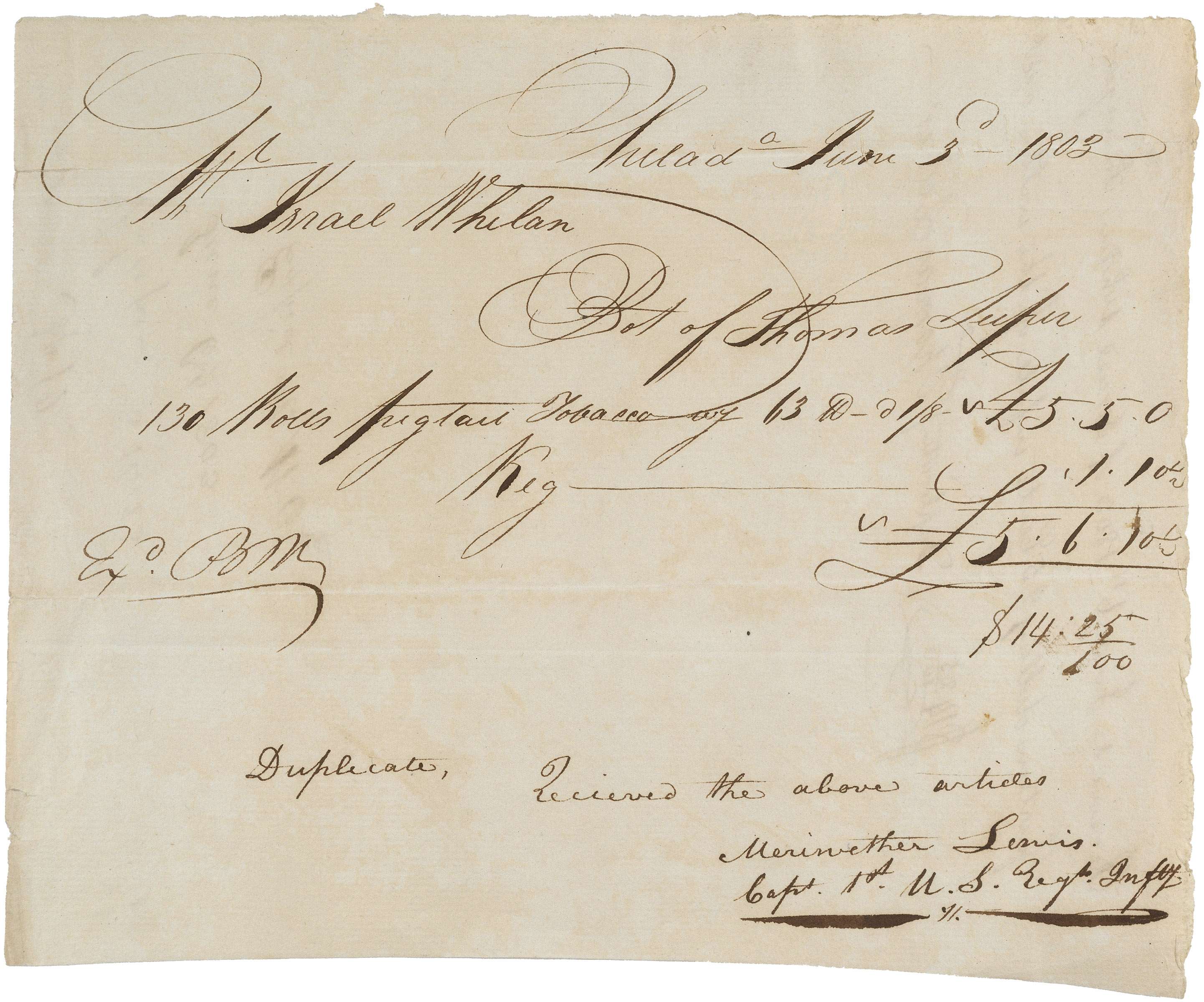

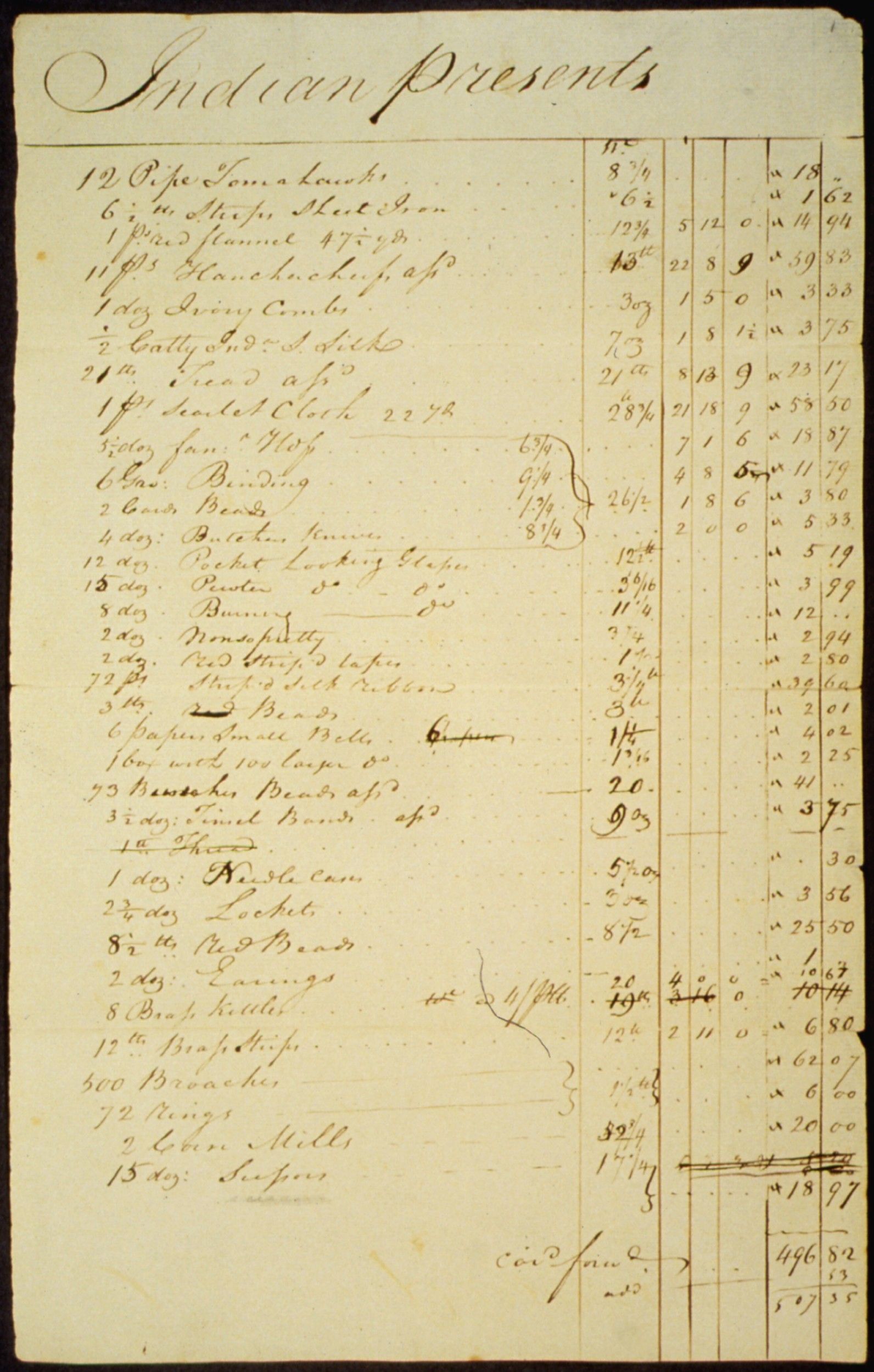

Lewis also started buying supplies for the trip—lots and lots of supplies. The National Archives has in its holdings receipts for several of Lewis’ purchases, including one for wine and kegs, one for 130 rolls of pigtail tobacco, and one listed as “Indian Presents,” which included pipe tomahawks, red flannel and silk, ivory combs, beads of all descriptions, butcher knives, small mirrors, ribbon, bells, needle cases, scissors, lockets, earrings, rings, broaches, brass kettles, and corn mills.

Receipt for 130 rolls of pigtail tobacco

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

List of Indian presents

Source: NARA’s DocsTeach

These receipts represent only the tip of the iceberg of Lewis’ and Clark’s purchases. Lewis bought more goods in Philadelphia, at the armory in Harper’s Ferry, and in Tennessee. He also drew from the public stores, for which he would not have been charged, items such as powder horns, shoes, knapsacks, inkstands, and blankets. When he reached St. Louis and met up with his co-captain, William Clark, they then purchased more odds and ends, including candles, vinegar, honey, and tools. They spent the winter of 1804 at Fort Mandan, near what is now Washburn, North Dakota, where they purchased yet more provisions—rations, whiskey, and salt—before they pushed off upstream for parts unknown on April 7, 1805.

Why did they need all this stuff? Well, it was a long, long trip—almost 8,000 miles, every mile of which they traversed by flatboat, canoe, and on foot, and there were no places to reprovision along the way. The members of the corps hunted and fished along the way to supplement their supplies, but practically everything else they needed, they had to carry with them. Furthermore, an important part of their mission was diplomacy—hence, the presents they carried to hand out to the Indians they met on their travels. Despite all their careful preparations, however, the expedition ran out of whiskey, salt, and tobacco before they reached St. Louis on their return trip.

Transaction Voided

Lincoln’s canceled paycheck

National Archives Identifier: 5743039

As a federal employee, the President of the United States draws a salary that he receives, just like every other worker. Dated April 5, 1865, this canceled check in the amount of $1,981.67 was for Lincoln’s monthly salary. At the time, the President’s yearly salary was $25,000.

Suspicious Purchase

Check for purchase of Alaska

National Archives Identifier: 301667

The National Archives has in its holdings a big, big treasury warrant (the equivalent of a canceled check): $7.2 million dated March 30, 1867, the equivalent of $140,753,675.68 in 2023 dollars. Secretary of State William Seward had brokered a deal with the Russian Minister to the United States Edourd de Stoeckl to sell Alaska to the U.S., thus putting an end to nearly 150 years of Russian exploration and colonization of that territory.

Seward had long been interested in acquiring Alaska, and Russia, weakened by the Crimean War and thus lacking the resources to keep exploring the area, first proposed selling it to the U.S. in 1959. The Civil War intervened, and Seward couldn’t devote his attention to the matter until 1867.

Many people roundly criticized the transaction—they just could not imagine what good such a remote and frozen territory would do to the country. They called Alaska “Seward’s Folly” and “Seward’s Icebox.” In 1896, the Klondike Gold Strike promptly ended all such objections.

View this profile on InstagramNational Archives Foundation (@archivesfdn) • Instagram photos and videos