The First Presidential Sequel

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy AdamsNational Archives Identifier: 528668

Founding Father-and-Son

On the Fourth of July, we often think of America’s iconic Founding Fathers, including Thomas Jefferson and John Adams. These great thinkers left their mark on their country, but only one of them saw a child of theirs ascend to the Presidency: John Quincy Adams. The eldest son of Massachusetts’ own John Adams, John Quincy went on to create his own legacy in the Presidency and beyond.

Serving as a lawyer, Secretary of State, U.S. Representative, and Senator on top of becoming our sixth President, John Quincy Adams led a busy, impactful life. Let’s delve into some of his major accomplishments beyond the Presidency through the National Archives catalog.

In this issue

Early Diplomatic Career

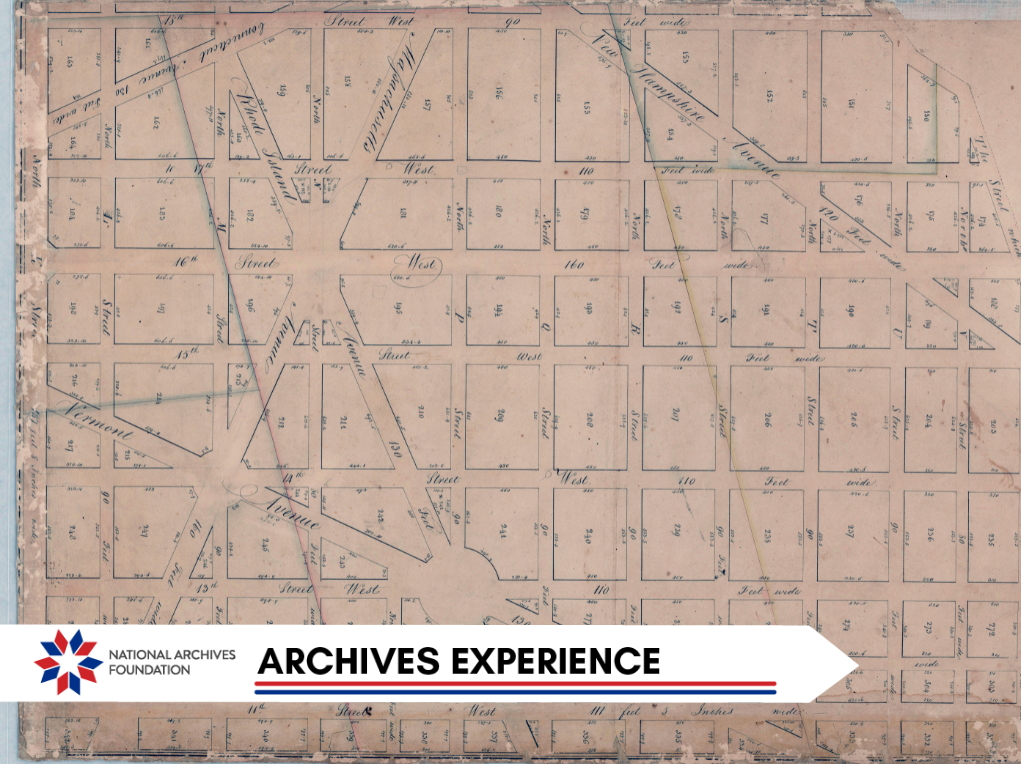

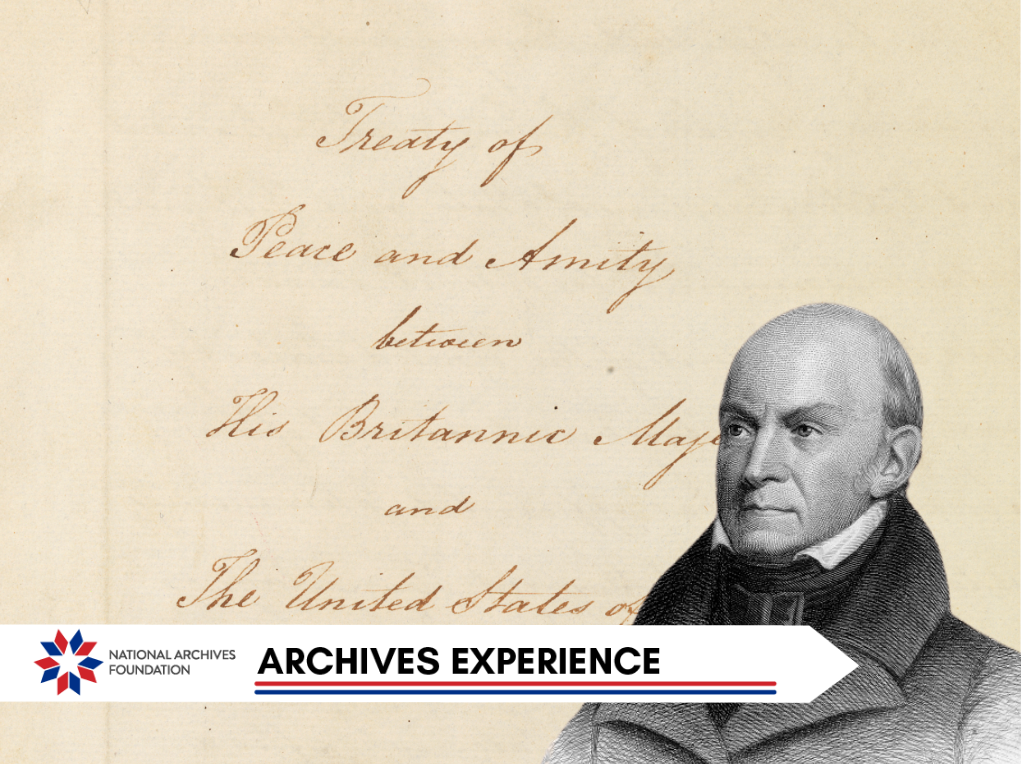

As the lead negotiator for the United States in the talks that ended the War of 1812, John Quincy Adams readily demonstrated his penchant for diplomacy. By late 1814, both the United States and Britain were exhausted from the war, which had been costly and inconclusive. Neither side had achieved a decisive victory, and both were facing mounting military and territorial challenges on other fronts. Thus, Adams’ role in negotiating the Treaty of Ghent bolstered his reputation as a capable diplomat and statesman.

The successful conclusion of the treaty also contributed to a sense of national pride and reinforced American sovereignty in the age of the early republic. The treaty established a number of provisions, including the cessation of hostilities between the two nations, regaining territorial status quo, and clarifying boundaries in Canada.

The Treaty of Ghent, 1814

National Archives Identifier: 5730368

Acquiring the Sunshine State

John Quincy Adams played a pivotal role in the United States’ acquisition of Florida while he was Secretary of State. He was instrumental in negotiating the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819 with Spain, which ultimately secured eastern Florida for the nation. He successfully convinced Spain to cede its claims to Florida in exchange for the United States recognizing Spanish sovereignty over Texas, then part of Spanish-held Mexico. This acquisition marked a tangible expansion of U.S. territory and solidified Adams’ reputation as a shrewd diplomat and key architect of American foreign policy during the early 19th century.

U.S. Senator Lawton Chiles of Florida and Fifth Archivist of the U.S. Dr. James Rhoads examining the 1819 Adams-Onís Treaty

National Archives Identifier: 23856419

Nineteenth-century map of Florida

National Archives Identifier: 271844220

Preserving America’s Story

During his term as Secretary of State under President James Monroe, in 1820, John Quincy Adams commissioned William J. Stone to make an exact-size facsimile of the Declaration of Independence with the signatures as well as the text. An engraver in Washington, D.C., took nearly three years to produce the facsimile. It was officially finished on June 5, 1823, almost exactly 47 years after Jefferson’s first draft of the Declaration.

Because photography and photocopiers did not exist in 19th-century America, important documents like the Declaration of Independence could only be reproduced via tracing or through the use of a device called a pantograph. Stone used a copperplate.

The Stone engraving of the Declaration is now the most widely circulated image of the document in the world, but it is familiar to most Americans because it is commonly reproduced in textbooks and posters. The National Archives is currently treating the copperplate engraving for long-term conservation. Read more about it here.

1823 Stone Engraving

National Archives Identifier: 1656605

Becoming an Abolitionist

While Adams was undoubtedly a gifted diplomat, his achievements in the courtroom remain a major piece of his legacy, specifically because of the Amistad case. In 1839, the schooner Amistad was carrying enslaved Africans to the Caribbean, where they would be forced to work for Spanish plantation owners. The Africans took control of the ship, killing the captain. However, the ship was seized off the coast of New York and taken to Connecticut. The ordeal sparked a major legal and humanitarian crisis that escalated to the Supreme Court.

Old Supreme Court Chambers where the Amistad case was argued

National Archives Identifier: 7718577

Adams took on the captives’ legal defense pro bono. The 73-year-old patriot argued passionately for their rights before the Supreme Court for over eight hours. Adams made the revolutionary case that maritime law mandated that the enslaved Africans, in overtaking the ship’s control, had seized all property on the ship, including themselves. Their circumstances rendered them free men. The justices agreed with him.

John Quincy Adams’s Request for Papers Relating to the

Lower Court Trials of the Amistad Africans

National Archives Identifier: 301671

The case underscored Adams’ belief in the principles of liberty and equality, concepts he was well versed in from his father’s work. Adams was a prominent advocate for abolitionism and used his position in Congress to push for antislavery measures.

Workhorse Until the End

After he was President, Adams lived with his wife on the property now known as Meridian Hill Park in northwest Washington, DC. While the house is no longer there, the public still enjoys the beautiful park.

Meridian Hill Park photographed in 1972

National Archives Identifier: 117692321

Known as “Old Man Eloquent” in Congress, Adams worked in government and legal affairs for the rest of his life. He is still the only U.S. President to return to the legislative branch after serving as President. After a debate on the House floor in 1848, the Representative from Massachusetts suffered a stroke. Some of his colleagues carried him to the Speaker’s room, where he passed away two days later.

Adams’ storied legacy and his advocacy efforts shaped the fledgling nation in countless ways. Celebrate patriots like John Quincy Adams and more this Fourth of July, and don’t forget that precious family time too, wherever you may be!