Roaring Fire

Why did the Chicago City Council need to exonerate a cow in 1997? For more than a century, the cow in question had been accused of kicking over a lantern that started the Great Chicago Fire. But even though this myth was debunked in 1893, it became ingrained in local lore—partially because the cow belonged to the O’Leary family. The combination of historic distrust of Catholics and rise in anti-Irish sentiment made this impoverished family the perfect scapegoat for the disaster. But we’re here to set the record straight…

In this issue

Ignition

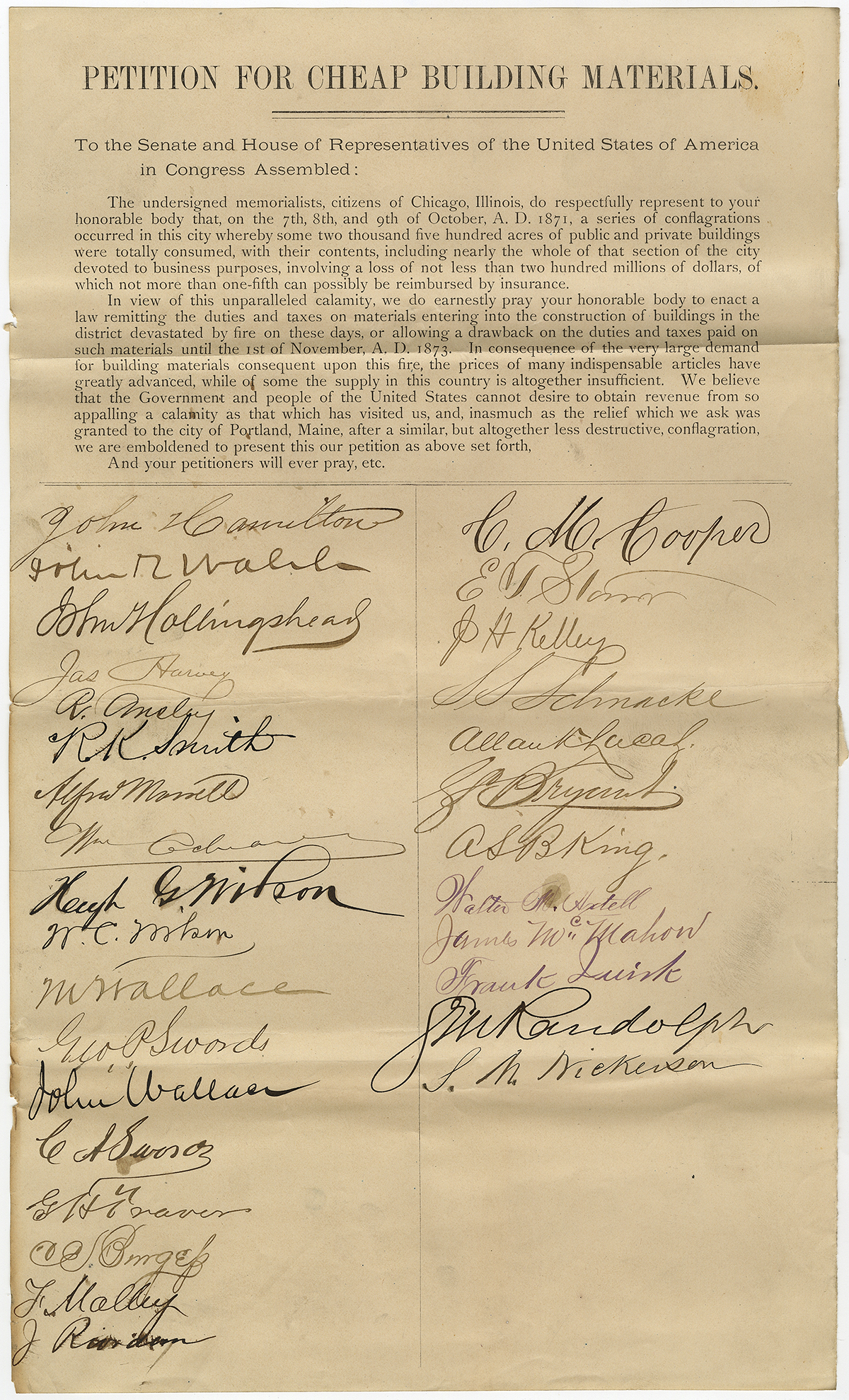

Starting on October 8 and lasting until October 10, 1871, the Great Chicago Fire burned about 3.3 square miles of the city of Chicago to the ground. It destroyed more than 17,000 structures, left more than 100,000 people homeless, and killed 120 people for certain, although the number may have been as high as 300.

Exacerbated by a long, dry summer, the fire started in or around a barn owned by Catherine and Patrick O’Leary on an alley behind 137 W. DeKoven Street, a block north of Roosevelt Road and roughly a mile west of the present-day location of Grant Park, the Field Museum, and the Shedd Aquarium. Exactly how the fire got started has been the subject of considerable speculation—some have stated that Mrs. O’Leary’s cow (named Daisy or Madeline or Gwendolyn, depending on who’s telling you the story) kicked a lantern over in the barn, while others thought that one of a bunch of men gambling in the barn may have knocked a lantern over and thus started the blaze.

Forty years after the fire, Chicago Tribune reporter Michael Ahern confessed that he and two now-deceased friends made the entire cow story up. Others have also taken credit for the cow legend. Perhaps ironically, because of the direction the wind was blowing, the O’Learys’ house was spared, although their barn was not.

Regardless of its origins, the Great Chicago Fire is a textbook example of Murphy’s law, because anything that could go wrong most certainly did. Strong winds from the southwest quickly blew the tiny fire into a roaring conflagration. A fire that strong creates its own wind gusts, which in this situation started picking up embers and blowing them further west. Practically every building and sidewalk in Chicago was made of wood at the time, so the fire found plenty to feed on.

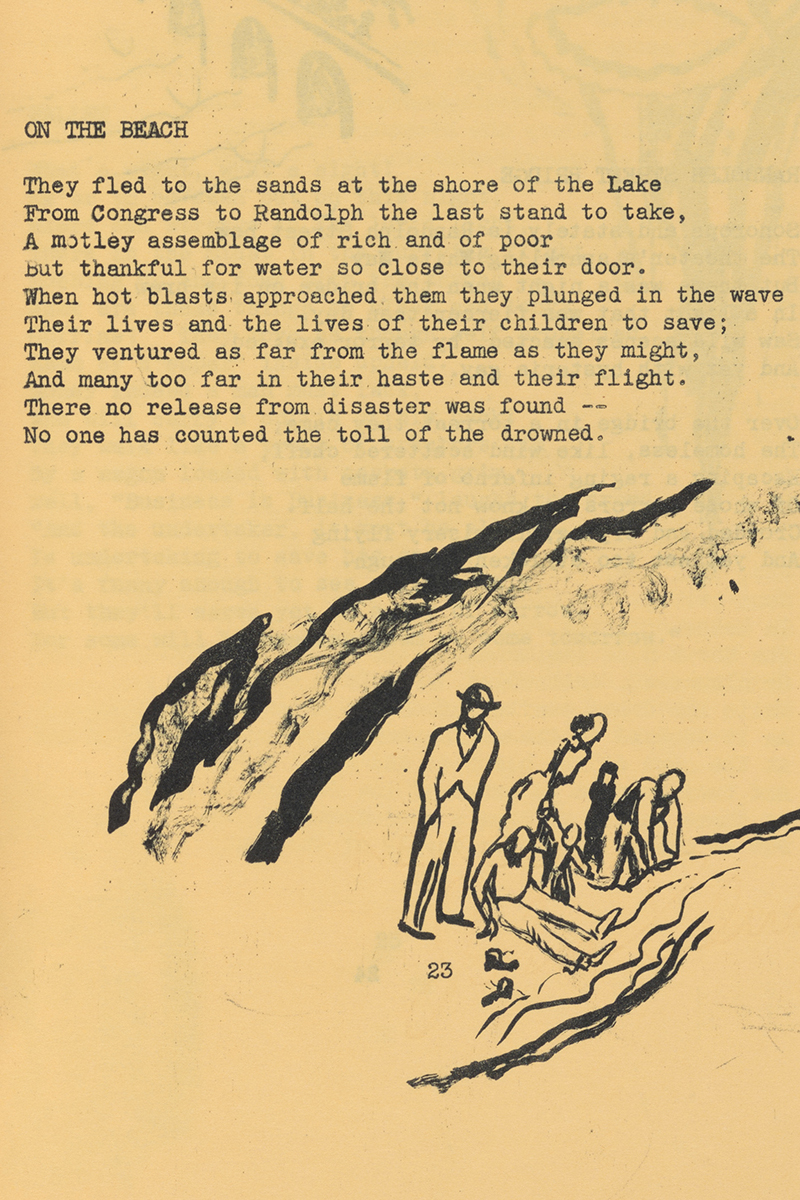

From a collection of WPA poems about the fire

National Archives Museum

From a collection of WPA poems about the fire

National Archives Museum

Roaring

General Phillip Sheridan

National Archives Identifier: 167248750

The Chicago Fire Department has a long and distinguished history, having been established as a paid firefighting force in 1858. When the department was called out to fight this fire, it had 185 firefighters, but only 17 horse-drawn steam pump trucks. When the alarm came in, the firefighters were sent to the wrong address, an error that took some time to rectify. About midnight, the fire jumped the South Branch of the Chicago River and ignited the South Side Gas Works, another serious setback to getting it under control.

The fire then raced northwest, toward the center of the city. The courthouse caught fire sometime after midnight, and the mayor ordered the prisoners in the basement set free and the rest of the building evacuated. At 2:30 a.m., the building collapsed in flames, sending the bell in the cupola crashing into the street.

Superheated tornado-like spirals of air carried embers across the main branch of the Chicago River and onto a railroad car full of kerosene. Then a flaming timber fell onto the roof of the city’s waterworks, setting the building on fire and destroying the citywide water system. The firefighters continued to battle the blaze with whatever they had at hand, but the water mains had gone dry throughout the city. On the evening of October 9, it started raining, but the fire had already spread into more sparsely populated areas on the north side and was burning itself out. Even when the flames were finally out, however, the rubble continued to smolder for days.

Gerald Sheridan and staff of 17

National Archives Identifier: 529949

On October 11, Mayor Roswell B. Mason put General Philip H. Sheridan in charge of preserving the “good order and peace of the city.” Martial law was declared, and Sheridan’s troops, a mix of regular army, police, civilians, and militia groups, patrolled the streets to control looting and violence. On October 24, they were dismissed, and the city took back responsibility for maintaining order.

The population of Chicago before the fire was about 324,000, and at least 100,000 lost their homes in the conflagration. Although 120 bodies were identified, the death toll was more likely closer to 300. Property damage amounted to $222 million dollars.

Embers

Even before the fire was under control, donations of money, food, clothing, firefighting equipment, and other goods were pouring into Chicago from across the country and around the world. Once the fire was out, city officials opened public buildings to serve as shelters for the homeless and outlawed price gouging for foodstuffs and other essentials. Saloons were ordered to close at 9 p.m. to preserve public order.

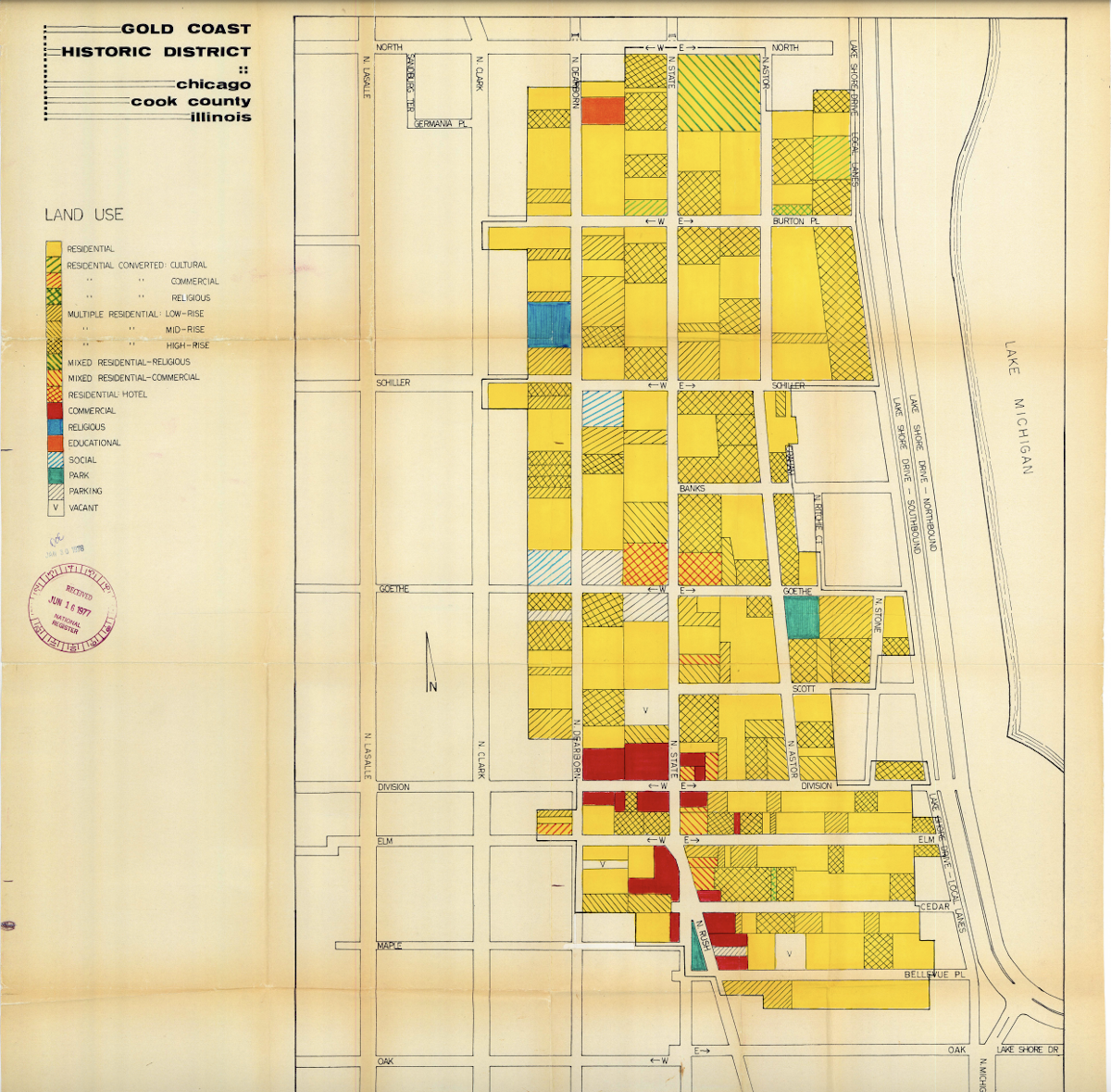

The city also started to develop building standards designed to prevent another massive fire from happening in Chicago. The fire department initiated a program of fire standards, working in cooperation with insurance companies

One serendipitous development that came out of the fire was that massive donations of books arrived in Chicago, more than 8,000 volumes from the city of London alone. In the spring of 1872, the Chicago City Council established the free Chicago Public Library to house all the books. Up until this time, all libraries in Chicago had been private subscription organizations that required their members to pay a fee to use their facilities.

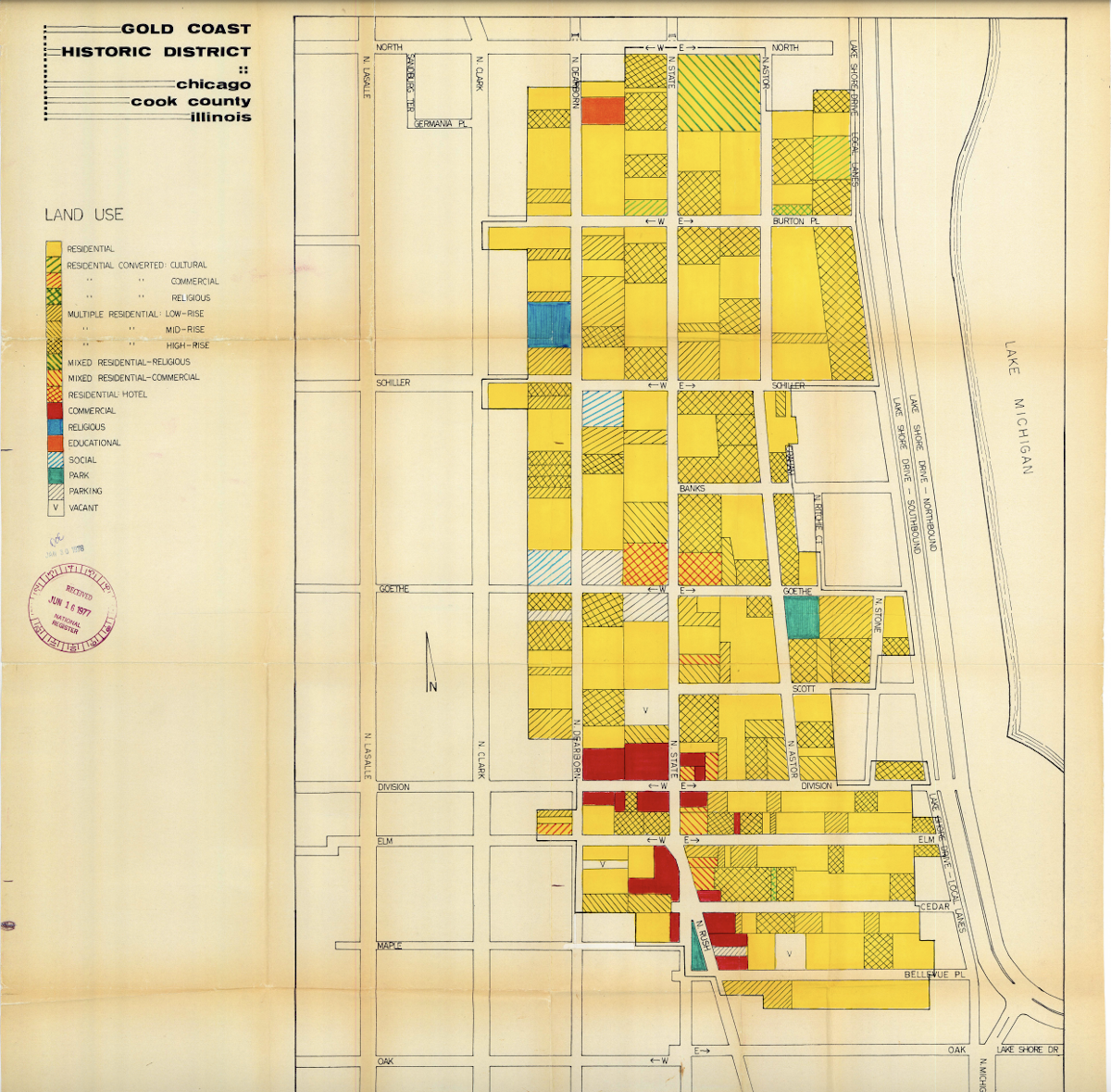

Six buildings survived the fire: St. Michael’s Church in Old Town; the Chicago Water Tower; the Chicago Avenue Pumping Station; St. Ignatius College Prep; Police Constable Bellinger’s cottage at 21 Lincoln Place, now 2121 North Hudson; and 2323 and 2339 North Cleveland Avenue. All are still standing. The structures on the O’Leary’s property that had survived the fire were torn down in 1956 and the Chicago Fire Academy was built on the site.

Repair

Many of the documents you’ll see below survived the Great Chicago Fire, but not without extensive damage. But these records were extremely important—many of them belonged to the U.S. Circuit Court and Illinois District Court, which were completely decimated by the fire.

But not all hope was lost. Archivists and the preservation teams at the National Archives were able to help. In 1949, work began on some of the recovered records of these courts. The documents were in dire condition. They were dry, wrinkled or curled in balls, discolored by scorch marks, and had calcined edges. The first step in repairing them was to remoisturize the paper. Individual documents, or documents clustered together, were placed on stainless steel shelves in a sealed room. A fog machine then filled the room with mist, slowly allowing the documents to reabsorb moisture. Once this process was completed, documents that were stuck to each other were separated.

To preserve these documents from further damage, each piece of paper was put between 2 steel plates and layers of thermoplastic foil. Heat and pressure were applied to melt the foil into the paper and seal it, a process now known as lamination.

On July 18, 1974, the National Archives opened a facility in Chicago. The facility now holds more than 140,000 cubic feet of records from the early 1800s to the early 2000s, including records and maps from federal courts and 85 federal agencies from across six states.

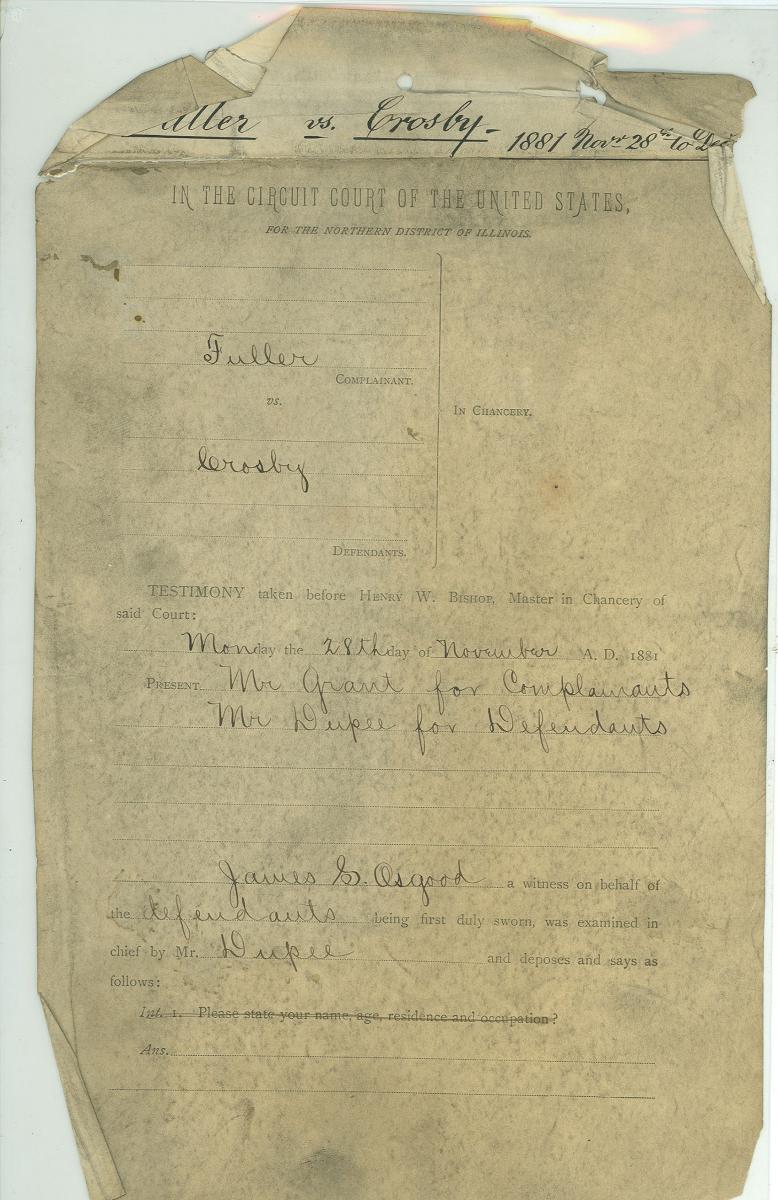

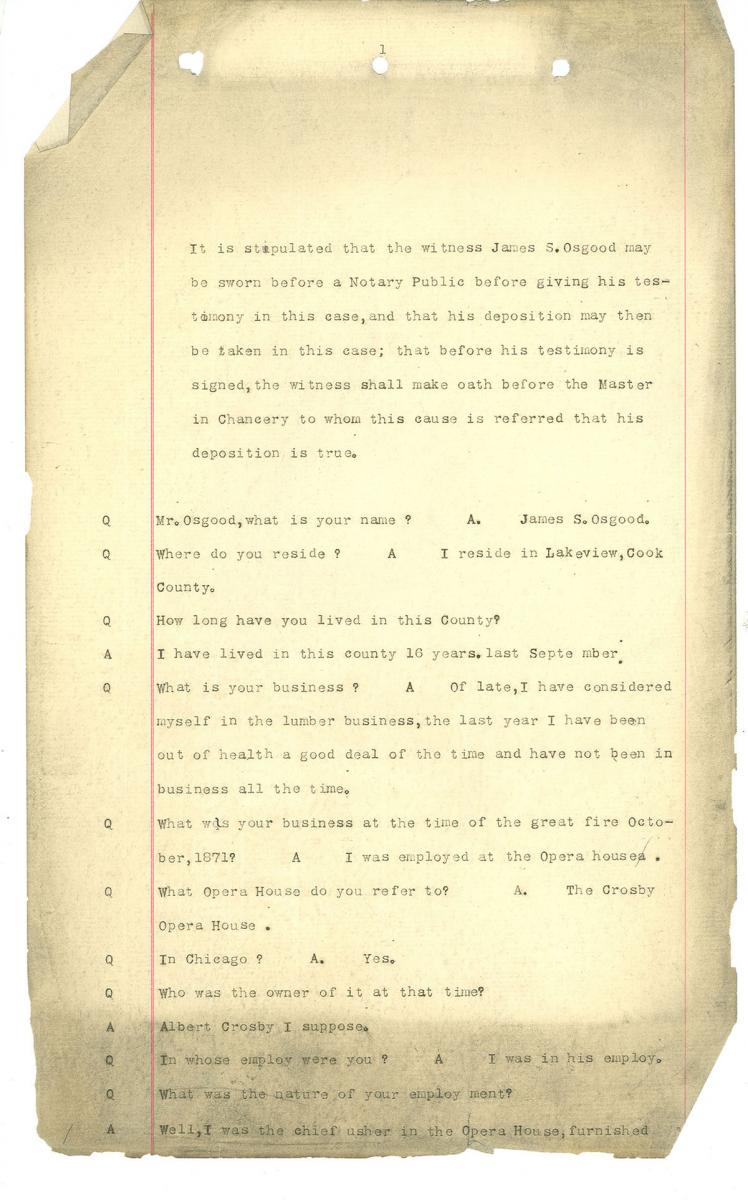

Fuller v. Crosby, 1881–a fully eyewitness account of the fire

Source: NARA’s Prologue Magazine

Part of the testimony from Fuller v. Crosby that touches on the fire

Source: NARA’s Prologue Magazine

Testimony of Jerome Osier in Admiralty and Law Case 3345, John T. Bothwell v. The Vessel Owners Towing Company

National Archives Identifier: National Archives Identifier: 200185182

NARA press release about the documents damaged in the fireNational Archives Identifier: 74228298

View this profile on Instagram

National Archives Foundation (@archivesfdn) • Instagram photos and videos