Reflecting on the Founders

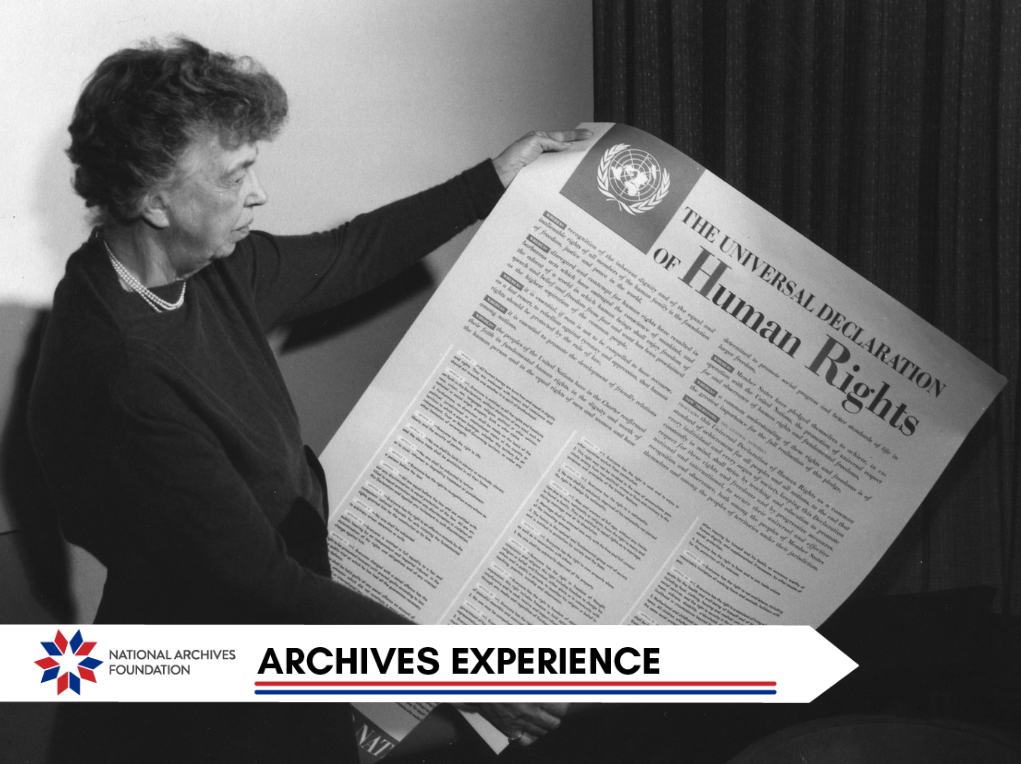

“What would the Founding Fathers think?” is an evergreen question in our country. It’s often asked when our country is at a crossroads or at times when we face a constitutional conundrum. Thanks to the Archives, the words of the Founders are always accessible. Their letters, notes, diaries, and official documents have influenced many Americans: elementary schoolers learning the Declaration, ConLaw students, the biggest fans of Hamilton, and sitting Presidents of the United States.

To chart a path forward, Americans have always looked backward. In this week’s newsletter, the words of the Founders aren’t just found in their original documents – they come back to life through our modern Presidents who were facing challenges like passing landmark legislation, overcoming distrust in government, and picking up the pieces in the wake of tragedy. Invoking the Founders isn’t just about the technicalities of constitutional questions. It’s about continuing their legacy of speaking truth to power, citizens’ involvement in the democracy process, and always striving for a more perfect union.

Here’s what our Presidents had to say.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Good Government

President Lyndon B. Johnson Signing the Medicare Bill

National Archives Identifier: 596403

Lyndon Baines Johnson was one of the most complicated men who has served as President of the United States. Elevated to the presidency upon the assassination of John F. Kennedy in November 1963, he soon embarked upon an ambitious legislative agenda that he named “The Great Society,” domestic policies intended to expand Medicare, Medicaid, public services, urban and rural development, civil rights, and education. By the fall of 1965, Johnson had worked with Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Johnson then turned his attention to education, believing that his own public education had delivered him from a life of poverty in rural Texas.

President Lyndon B. Johnson and President Harry Truman After Signing Medicare and Medicaid into Law

National Archives Identifier: 236741916

On November 8, 1965, Lyndon Johnson spoke to Southwest Texas State College just before he signed the Higher Education Act of 1965 into law. In his remarks, he evoked another complicated man, the Founding Father Thomas Jefferson, who also put great stock in lifelong education: “This Congress did more to uplift education, more to attack disease in this country and around the world, and more to conquer poverty than any other session in all American history, and what more worthy achievements could any person want to have? For it was the Congress that was more true than any other Congress to Thomas Jefferson’s belief that: ‘The care of human life and happiness is the first and only legitimate objective of good Government.'”

Establishment of Medicare in 1966

National Archives Identifier: 236685533

Jefferson to community after his retirement

NARA’s Founders Online

A Visit from Ben

Reagan Board of Governor’s speech

People have long been fond of quoting Benjamin Franklin – let’s face it, the man was imminently quotable. At a dinner for the Board of Governors of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation on December 14, 1985, President Ronald Reagan speculated about what Franklin might think about the United States of the twentieth century. Reagan recalled that at the end of a play titled Benjamin Franklin in Paris,

“Franklin sits alone in the final act and wonders what he would find if after 200 years,

‘I, too, should rise up and stand once more on Pennsylvania land and walk and talk and breathe the free air. For I know in my heart it will be free. I know it—I know it even now. . .’

I think old Ben, were he to make such a visit, might be a little proud of what he would find. And he might even have a word or two of praise for what the American people have achieved.”

A Generational Inspiration

The Peacemakers

Art in the White House: A Nation’s Pride

Source: George W. Bush Library

Those who are fortunate enough to inhabit the White House are also privileged to live with one of the finest art collections in the world. President George H. W. Bush was particularly fond of a painting by George Peter Alexander Healy titled The Peacemakers. Completed in 1868, the painting depicts a meeting in March 1865 of Major General William T. Sherman, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, President Abraham Lincoln, and Rear Admiral David D. Porter aboard the Union sidewheel steamer River Queen to discuss the terms of the surrender of the Confederate Army. The three military men sit upright, while Lincoln leans forward, his right hand supporting his chin, deep in thought. President George H. W. Bush noted, “What we see in the distance is a rainbow – a symbol of hope, of the passing of the storm. The painting’s name, The Peacemakers … for me, this is a constant reassurance that the cause of peace will triumph and that ours can be the future that Lincoln gave his life for: a future free of both tyranny and fear.”

The Peacemakers

The Peacemakers hung in the White House Treaty Room from John F. Kennedy’s presidency through George W. Bush’s presidency. The painting also spoke to the younger Bush, particularly after the tragedy of 9/11. Recalling the painting’s evolving meaning to him, he said: “Before 9/11, I saw the scene as a fascinating moment in history. After the attack, it took on a deeper meaning. The painting reminded me of Lincoln’s clarity of purpose: he waged war for a necessary and noble cause.”

President Obama moved the painting to the private Oval Office dining room in the West Wing, where it hung throughout his presidency.

Bigger than One

Washington farewell address

Source: NARA’s Founders Online

At the end of June 2013, President Barack Obama, First Lady Michelle Obama, and their daughters Malia and Sasha traveled to Africa. In South Africa, they toured Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela had been held prisoner for eighteen years. On June 30, Obama spoke at Cape Town University, comparing Mandela to George Washington: “Now, I mentioned yesterday at the town hall – like America’s first President, George Washington, he [Nelson Mandela] understood that democracy can only endure when it’s bigger than just one person. So his willingness to leave power was as profound as his ability to claim power.”

Washington resigns commission in army

Source: NARA’s Founders Online

President George Washington had declined to run for a third term in 1796 because he was then sixty-three years old and he believed that he might die in office, which would create the impression that a President was elected to serve the nation for life. This was, in fact, the second time in his life that Washington had voluntarily ceded his power, the first being when he resigned his commission as commander-in-chief in the Revolutionary Army to Congress in 1783 in Annapolis, Maryland. Many people had assumed that Washington would be crowned king of the new nation, but instead, he retired to his beloved Mount Vernon as a private citizen. George Washington died at Mount Vernon on December 14, 1799.

Follow this link to view the full photo gallery of the Obamas visit to South Africa

on the Obama White House Archives site

The Union in Paine

Paine’s criticism of Great Britain

Source: NARA’s Founders Online

Thomas Paine is a Founding Father that most of us hear about when we’re first studying the Revolutionary War, when we’re about eleven or twelve, and then we don’t hear much, if anything, about him thereafter. He published his most famous work, “Common Sense,” in 1776. It was a direct attack on King George III of England, blaming him for the American colonists’ discontent, and it spread through the colonies like wildfire. By the end of the Revolutionary War, more than a half million copies were in circulation.

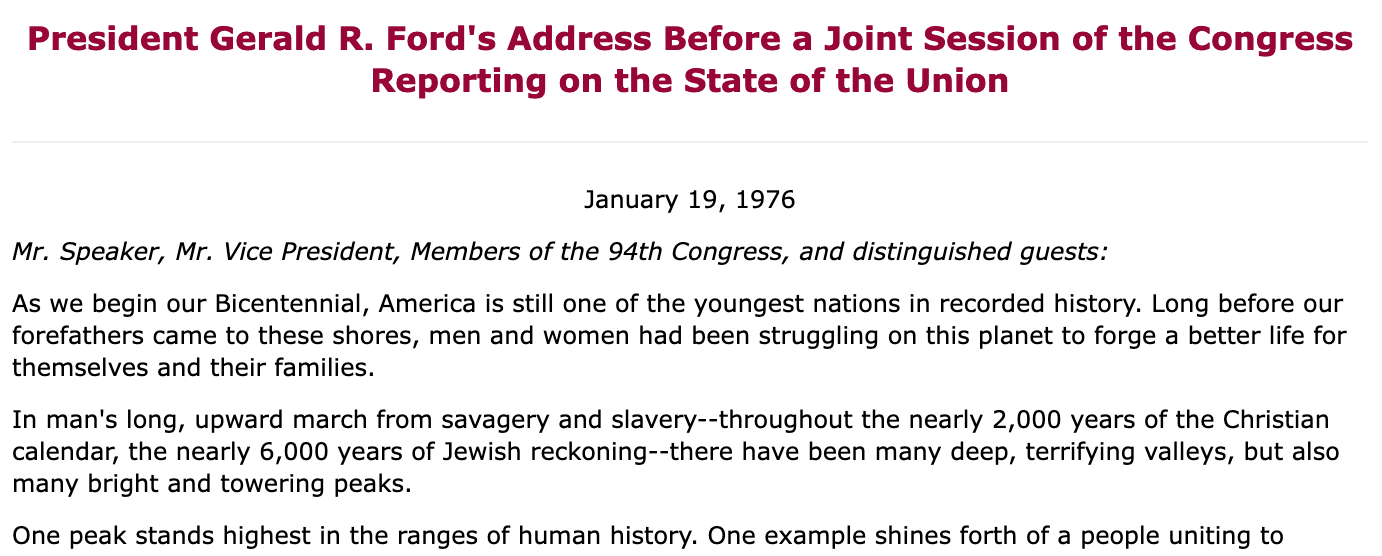

Gerald Ford’s 1976 State of the Union

Source: Ford Library

Two hundred years later, in his January 1976 State of the Union address, President Gerald Ford quoted from “Common Sense”:

History and experience tell us that moral progress comes not in comfortable and complacent times, but out of trial and confusion. Tom Paine aroused the troubled Americans of 1776 to stand up to the times that try men’s souls because the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. Just a year ago, I reported that the state of the union was not good. Tonight, I report that the state of our union is better in many ways, a lot better, but still not good enough. To paraphrase Tom Paine, 1975 was not a year for summer soldiers and sunshine patriots. It was a year of fears and alarms, and of dire forecasts, most of which never happened and won’t happen.

Paine went on to publish several other publications that encouraged the American colonists to stand fast in their fight for freedom from England. After the war ended, he went to England to solicit funding for a bridge over the Schuylkill River near Philadelphia, but he was soon moved to support the French Revolution, a cause he remained faithful to until the revolutionaries threatened the life of King Louis XVI. His two-part defense of the revolution, The Rights of Man, was banned in England, the publisher was thrown in jail, and Paine, who was on his way to France at the time, was tried in absentia and found guilty of seditious libel.

Many prominent Americans also supported the French Revolution at the beginning, but they began to withdraw their backing as events in France became more violent and bloody. Paine himself was jailed in 1793 over his objections to the execution of the king and his family. While he was imprisoned, the first part of his last great, three-part work, The Age of Reason, was published, and it was, so to speak, the last nail in the coffin of his popularity, because it promoted the philosophy of deism instead of organized religion and the Bible. Many people interpreted it as a defense of atheism, which did not win Paine many friends. Released from prison after nearly a year in late 1794, he returned to the United States, where he further tarnished his reputation by publishing a scathing letter to George Washington in which he accused the President of being an incompetent general and an imposter. Thomas Paine died in New York City in 1809.

Jefferson letter to Paine

Before reading the letter at the link above, consider the following

for some additional context

PrC (DLC); at foot of text: “Thos. Paine esq.” The pamphlets that TJ acknowledged were six copies of the second part of Rights of Man. Paine had sent Washington a dozen copies, designating half of them for TJ (Paine to TJ, 13 Feb. 1792; Paine to Washington, 13 Feb. 1792, DLC: Washington Papers; see Sowerby, No. 2826).

It is significant that TJ allowed another decade to pass before he again wrote to Paine. During this critical period he allowed all of Paine’s various letters to go unanswered (Paine to TJ, 20 Apr. 1792; 10 Oct. 1793; 1 Apr. and 10 May 1797; and 1, 4, 6, and 16 Oct. 1800). The reason seems obvious. A failure at almost everything save his great achievements as a political propagandist, Paine succeeded ultimately in alienating himself not only from such former friends as Washington, Adams, and TJ, but from the mainstream of events in England, France, and the United States as well. More and more he became obsessed with the idea that the American national character had deteriorated. “The neutral powers despise her for her meanness and her desertion of a common interest,” he wrote TJ in 1797, “England laughs at her for her imbecility, and France is enraged at her ingratitude and sly treachery” (Paine to TJ, 1 Apr. 1797). His hatred of the Federalists was so violent as to suggest mental derangement, leading him into the seditious act of planning the conquest of the United States by France. His letters of 1800 were such that TJ felt obliged, shortly after becoming President, to restate his inaugural pledge and to warn Paine that the United States would not become involved in European contests—even, he added, “in support of principles which we mean to pursue” (TJ to Paine, 18 Mch. 1801).