Progress at the Ballot Box: 60 Years of the Voting Rights Act

August 6, 2025 marks a significant milestone in the fight for civil rights: the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson, this legislation enshrined permanent protections for voters so they can always fulfill their democratic duty without discrimination or intimidation. Sixty years later, we reflect on what led President Johnson to advocate for this legislation.

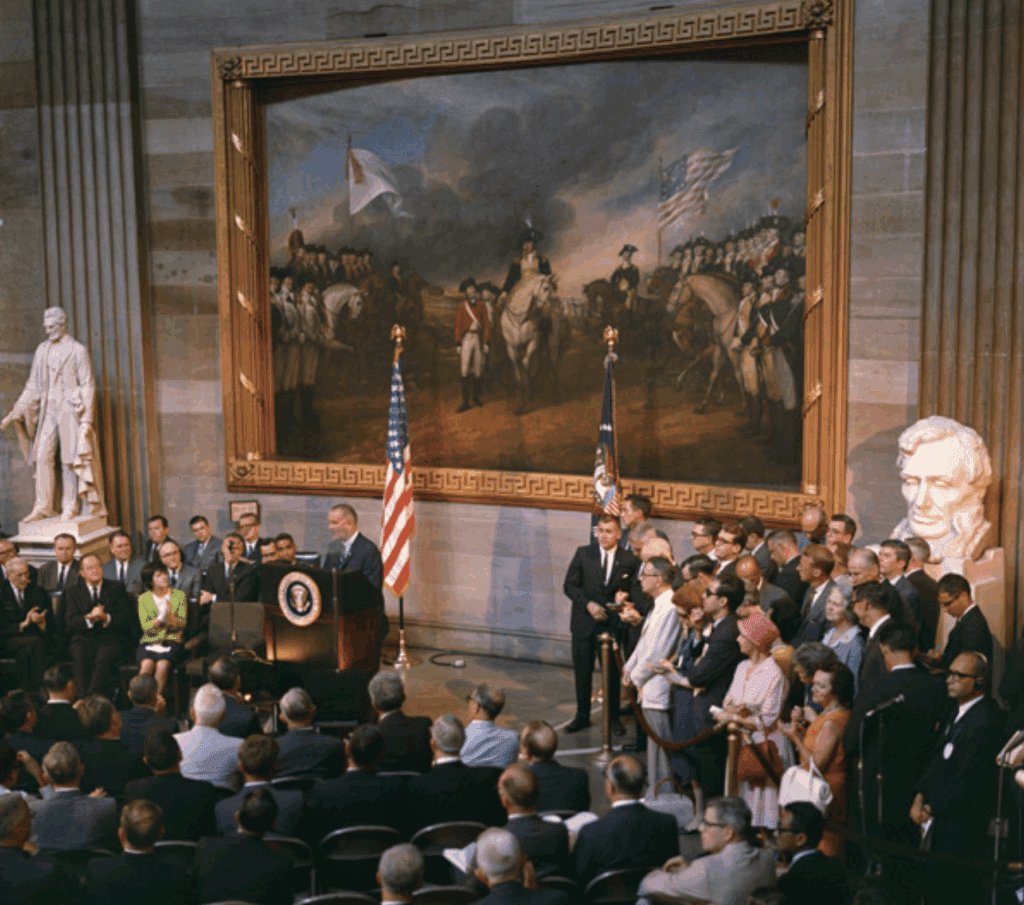

President Lyndon Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act as Martin Luther King, Jr., other civil rights leaders, and members of Congress look on (NAID 2803443)

Despite the fact that the 15th Amendment, passed in the wake of the Civil War, prohibited the denial of voting rights based on race, color, or previous condition of servitude, many states and local communities found ways to circumvent these protections. Through mechanisms like literacy tests, poll taxes, and intimidation, African American men were disenfranchised for nearly a century. Collectively, these are known as “Jim Crow” laws. Women had their own path to the ballot box and finally won the right to vote in 1920, which still did not solve the issue of racial discrimination at the voting booth.

The House Joint Resolution Proposing the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, December 7, 1868 (NAID: 299797)

By the 20th century, these Jim Crow laws were firmly entrenched, and discriminatory practices had spread across many aspects of society, not just at the ballot box. From vastly different conditions at public schools to separate public transit accommodations, the inequality toward African Americans deepened and the demand for change intensified, which set the stage for the Civil Rights Movement.

Photograph of a young woman holding a banner at the Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C., August 28, 1963 (NAID: 542030)

The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was a pivotal leader in the movement, first being instrumental in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Chiefly outlawing racial discrimination in the workplace and places of public accommodations, the act was a momentous step toward equality. Despite the wide-reaching impact of the law, it still did not address putting a stop to discriminatory practices against voting rights.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the 1964 Civil Rights Act as Martin Luther King, Jr., and others look on, 1964 (The Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library)

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 (NAID: 299891)

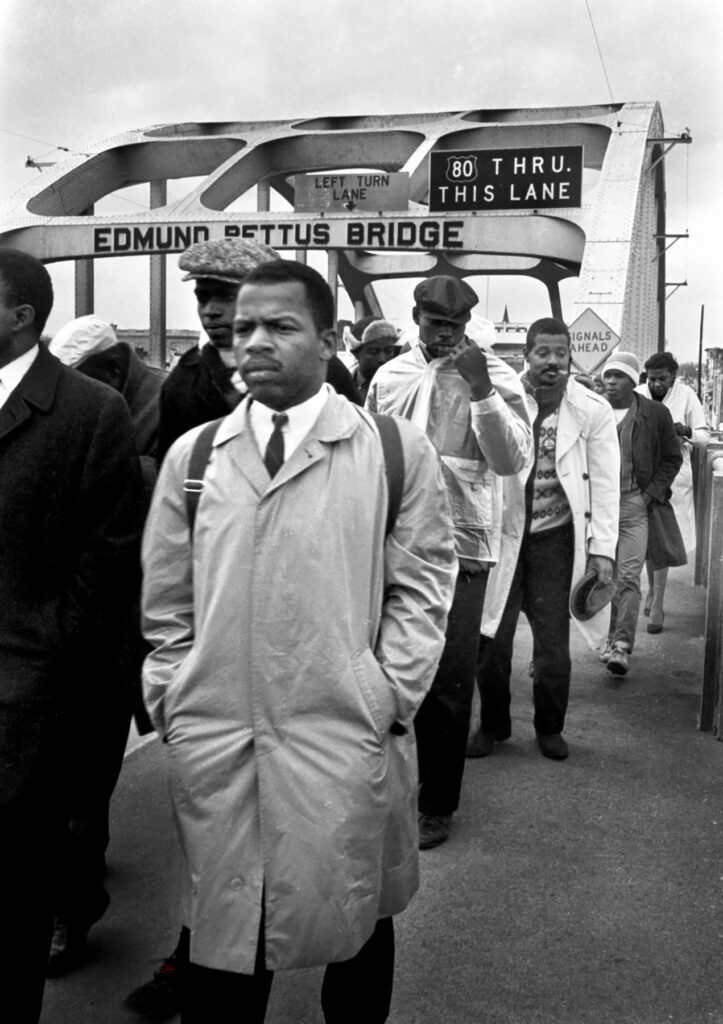

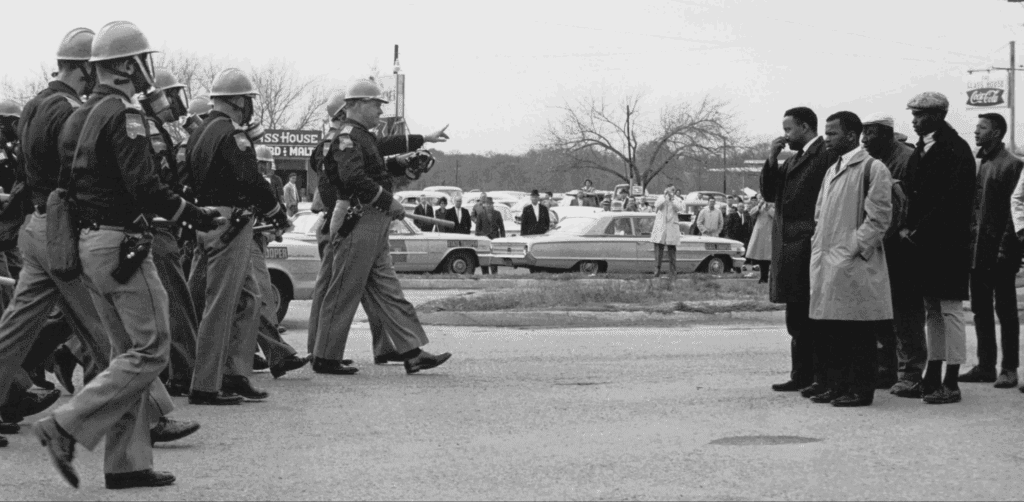

Seeing that voting inequality was still prominent in Southern communities, leaders such as activist John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) as well as Dr. King took bold action by leading several marches starting in Selma, Alabama toward the capital of Montgomery in March 1965. The main goals of the marches were protesting the violent denial of African American suffrage and raising awareness for a need for more federal protections. You can learn more about these marches and related records in the National Archives here.

John Lewis during the "Bloody Sunday" march (NAID: 222097049)

Photograph of the Two Minute Warning on Bloody Sunday (NAID: 16899041)

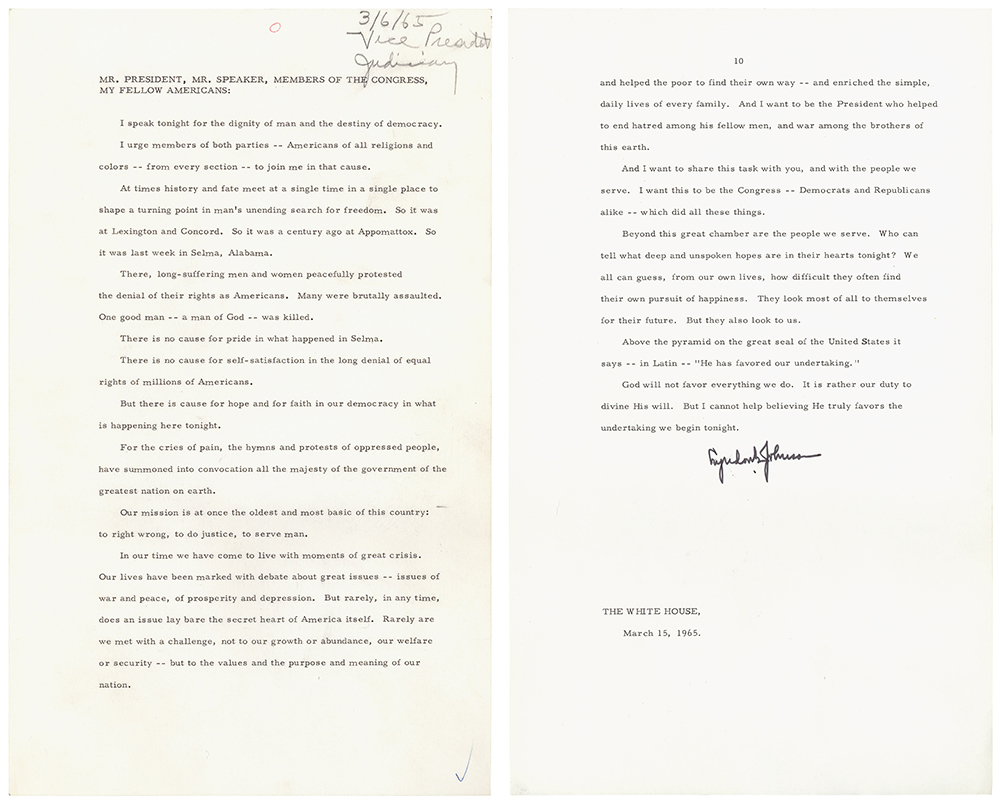

The nonviolent marches were both met with violence by Alabama law enforcement. The media visibility captured the nation’s attention, and just days later, President Johnson made his support of the Selma marchers clear in a national address before Congress, known as the “We Shall Overcome” speech. The address is available in the National Archives catalog and online through the LBJ Presidential Library.

"Our fathers believed that if this noble view of the rights of man was to flourish, it must be rooted in democracy. The most basic right of all was the right to choose your own leaders. The history of this country, in large measure, is the history of the expansion of that right to all of our people.

Many of the issues of civil rights are very complex and most difficult. But about this there can and should be no argument. Every American citizen must have an equal right to vote."

President Lyndon Johnson’s speech to Congress on voting rights, March 15, 1965 (NAID: 5753156)

Three days later on March 18, Congressman Emmanuel Celler sent a telegram inviting Dr. King to Washington to testify in support of the Voting Rights bill before the Judiciary Committee. However, King chose to remain with the marchers, delivering a speech at the Alabama State Capitol instead. After nearly six months of Congressional deliberations alongside the efforts of Dr. King and other civil rights activists, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Act into law on August 6, 1965.

President Lyndon Johnson delivers remarks at the signing ceremony for the Voting Rights Act in the Capitol Rotunda (NAID: 2803442)

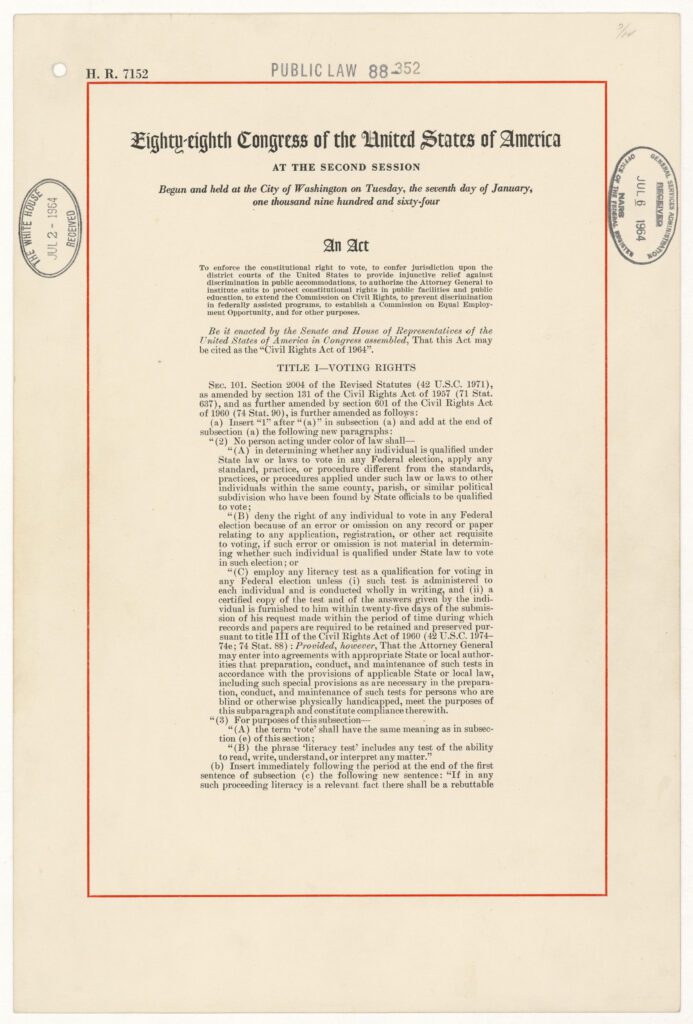

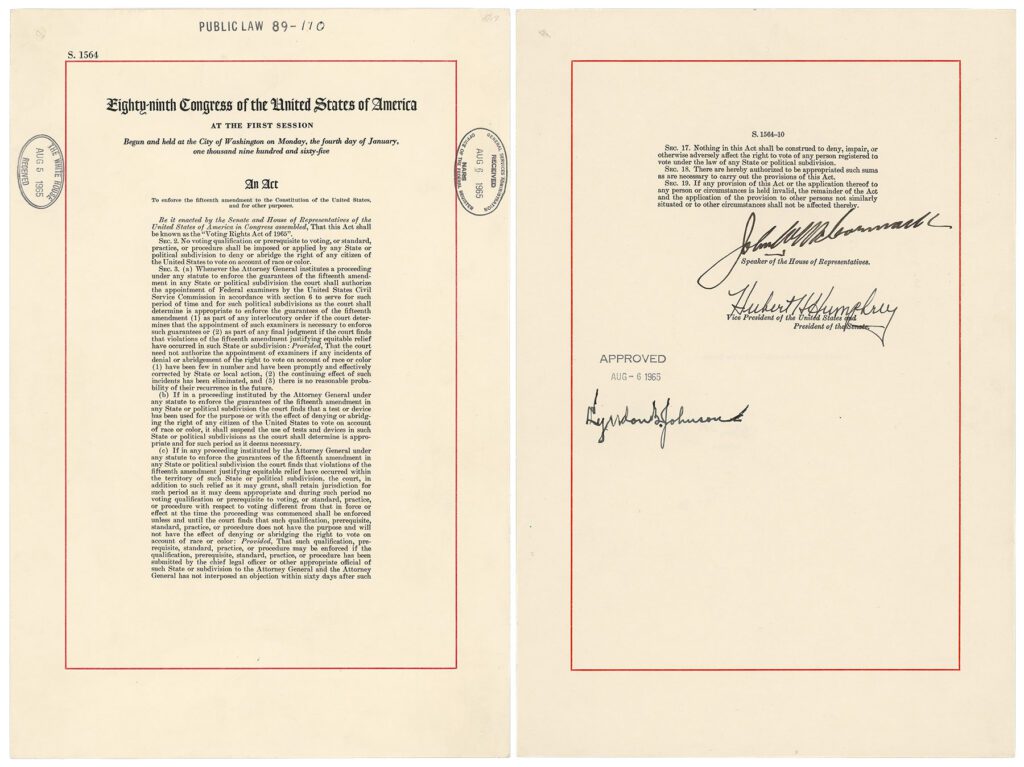

The Voting Rights Act (NAID: 299909)

Formally titled “An Act to Enforce the Fifteenth Amendment,” the Voting Rights Act prohibited literacy tests and other devices that hindered voting, giving the Justice Department the authority to enforce compliance in individual states. The 24th Amendment, certified in 1964, had already abolished poll taxes in federal elections, so the Voting Rights Act extended this to state and local elections. By the end of 1965, over 250,000 new Black voters had registered to vote.

As with other major legislation in American history that the American public is divided on, the effects of the Voting Rights Act were not immediately realized because it faced both court challenges and practical obstacles on the ground. Over the course of the Civil Rights movements of the 1950s and 1960s, many lost their lives fighting for this fundamental right, but the legacy of this effort and the promise to uphold the right to vote for all Americans lives on.

If you're in D.C. or planning to visit, the original Voting Rights Act signed by President Johnson will be on display in the museum through August 27, 2025.

Related Content